.jpg.webp)

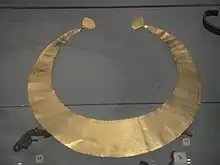

A gold lunula (pl. gold lunulae) was a distinctive type of late Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and—most often—early Bronze Age necklace, collar, or pectoral shaped like a crescent moon. Most are from Prehistoric Ireland.[1] They are normally flat and thin, with roundish spatulate terminals that are often twisted to 45 to 90 degrees from the plane of the body. Gold lunulae fall into three distinct groups, termed Classical, Unaccomplished and Provincial by archaeologists. Most have been found in Ireland, but there are moderate numbers in other parts of Europe as well, from Great Britain to areas of the continent fairly near the Atlantic coasts. Although no lunula has been directly dated, from associations with other artefacts it is thought they were being made sometime in the period between 2400 and 2000 BC;[2] a wooden box associated with one Irish find has recently given a radiocarbon dating range of 2460–2040 BC.[3]

Of the more than a hundred gold lunulae known from Western Europe, more than eighty are from Ireland;[4] it is possible they were all the work of a handful of expert goldsmiths, though the three groups are presumed to have had different creators. Several examples have a heavily crinkled appearance suggesting that they had been rolled up at some point. One Irish example, from Ballinagroun, has had its original Classical engraved decoration beaten over to erase it (not quite successfully), and then a new Unaccomplished scheme added (see below for these classifications).[5] This and the fact that it had been folded over several times suggest that it had been in use for a long time before it was deposited.[6] The first two examples illustrated show roughly the range of widths of the lowest part of the lunula that is found. Finds in graves are rare, perhaps suggesting they were regarded as clan or group property rather than personal possessions, and though some were found in bogs, perhaps suggesting ritual deposits, more were found on higher ground, often under standing stones.[7]

Most gold lunulae have decorative patterns very much resembling beaker pottery from roughly the same period, using geometrical patterns made up of straight lines, with zig-zags and criss-cross patterns, and many different axes of symmetry. The curving edges of the lunula are generally followed by curving border-lines, often with decoration between them. The decoration is typically most dense at the tips and edges, and the broad lower central area is often undecorated between the borders.[8] The decoration also resembles that on amber and jet spacer necklaces, which are thought to be slightly later in date.

Typology

Gold lunulae have been classified into groups as follows:[9]

- Classical, perhaps all made in Ireland, on average the widest, heaviest and also thinnest group. They are thin enough to be flexible when worn, and for the incised decoration to appear as relief on their underside. One aspect of the skill with which they are made is the variation in thickness across the piece, with the inner edge often three times thicker than the middle and the outer edge twice as thick.[10]

- Unaccomplished, similar in their range of design motifs, but narrower and less skillfully executed; a small number are undecorated.[11] All Irish.

- Provincial, so named as all except one example were found outside Ireland.[11] Thicker and more rigid, they were probably all or mostly made outside Ireland. Their decoration can be more varied, and is divided into two groups: "dot-line", found in Scotland and Wales, and "linear", found in Cornwall, Belgium and north Germany, as well as the Irish example. The northern coast of France has both types. Punches, not otherwise used in lunulae, are used for the dots in "dot-line" types.[12]

It used to be thought that these groups were produced in chronological sequence, but this is now much less certain, although the Ballinagroun lunula does show Unaccomplished decoration replacing Classical when it was reworked. In one large sample of 39 lunulae, the 19 Classical averaged 54 grams, with the 12 Unaccomplished averaging 40 gm.[7] Finds of Classical lunulae are concentrated in the north of Ireland, probably near the sources of gold, with Unaccomplished find spots mostly forming a "peripheral border" around this area. A few Classical lunulae have been found on the north Cornish coast and in southern Scotland.[12]

Three Provincial lunulae were discovered in Kerivoa, Brittany (Kerivoa-en-Bourbriac, Côtes-d'Armor) in the remains of a box with some sheet gold and a rod of gold. The rod had its terminals hammered flat in the manner of the lunulae. From this it is thought that Lunulae were made by hammering a rod of gold flat so it became sheet-like and fitted the desired shape. Decoration was then applied by impressing designs with a stylus. The stylus used often leaves tell-tale impressions on the surface of the gold and it is thought that all the lunulae from Kerivoa, and another two from Saint-Potan, Brittany and Harlyn Bay, Cornwall were all made with the same tool. This suggests that all five lunulae were the work of one craftsperson and the contents of the Kerivoa box their tools of trade.[13]

Lunulae were probably replaced as neck ornaments firstly by gold torcs, found from the Irish Middle Bronze Age, and then in the Late Bronze Age by the spectacular gorgets of thin ribbed gold, some with round discs at the side, of which 9 examples survive, 7 in the National Museum of Ireland.[14]

_01.jpg.webp)

The shape is sometimes found into the Iron Age, now also in silver, though the relation to the much earlier Bronze Age lunulae may be tenuous. A bronze example from the Welsh Llyn Cerrig Bach lake deposit (200 BC – 100 AD) has an embossed medallion with a triskele-based design in Celtic La Tène style, although it lacks the fastening at the back and has holes that are presumably for fixing it to a surface. It has been suggested it fitted around the pole of a chariot, or was attached to a shield, or worn by a statue.[15] Two silver examples from Chão de Lamas, Coimbra in Portugal of about 200 BC [16] should perhaps be considered as flattened and widened torcs; similar pieces are worn by figures in sculpture from the same culture.

Recent finds

The known corpus continues to expand slowly. The UK Portable Antiquities Scheme has recorded three incomplete finds in England in recent years, in 2008, 2012 and 2014, the last only missing one terminal.[17] In 2009 the Coggalbeg hoard surfaced in Ireland; it had actually been discovered in 1945 when cutting peat, but kept hidden. The hoard, including a lunula of the Classical type, is now in the National Museum of Ireland.[18]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The British Museum describe the (Irish) Blessington lunula (illustrated) as "Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age, 2400BC-2000BC (circa)", webpage

- ↑ Needham 1996, 124

- ↑ Cahill, 277, dates "CalBC (at 95% probability)"; 276–278 discuss the dating of Irish lunulae, without reaching very firm conclusions.

- ↑ Wallace, 49

- ↑ Taylor, 1980, 33; illustrated at Wallace 2:21

- ↑ Wallace, 60

- 1 2 Taylor, 1980, 28

- ↑ Wallace, 49–50; Taylor 1980, 28ff

- ↑ Wallace, 50; Taylor 1980, 27 onwards

- ↑ Taylor, 1980, 35

- 1 2 Waddell, 1998, 135

- 1 2 Taylor, 1980, 33

- ↑ Taylor, 1980, 34

- ↑ Wallace, 88–89; 3:19–25

- ↑ National Museum of Wales, "Crescentic-shaped plaque"

- ↑ Emerick, Carolyn; Authors, Various (28 February 2018). "Europa Sun Issue 3: February 2018".

- ↑ Portable Antiquities Scheme Database, accessed 23 March 2015

- ↑ "Stolen treasure: The Coggalbeg Hoard". Irish Archaeology; The Roscommon Lunula – Gold Lunula and discs found in Roscommon, Ireland - the breaking story

References

- Cahill, Mary, John Windele's golden legacy—prehistoric and later gold ornaments from Co. Cork and Co. Waterford, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol. 106C, (2006), pp. 219–337, JSTOR

- Needham, S. 1996. "Chronology and Periodisation in the British Bronze Age" in Acta Archaeologica 67, pp121–140.

- Taylor, J.J. 1968. "Early Bronze Age Gold Neck-Rings in Western Europe" in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 34, pp. 259–266

- Taylor, J.J. 1970. "Lunulae Reconsidered" in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 36, pp. 38–81, also in

- Taylor, Joan J. 1980, Bronze Age Goldwork of the British Isles, 1980, Cambridge University Press, google books

- Waddell, John. The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland. Galway: Galway University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-1-8698-5739-4

- Wallace, Patrick F., O'Floinn, Raghnall eds. Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland: Irish Antiquities, 2002, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, ISBN 0-7171-2829-6

External links

- "Early Bronze Age Technology and Trade: The Evidence of Irish Gold", By Joan J. Taylor, Penn Museum

- Looking at lunulae, video lecture by Dr. Mary Cahill, NMS Archaeology Conference 2022

- The Penwith Lunula

- Treasures of early Irish art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D., an exhibition catalogue from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Gold lunula (cat. no. 2)