| Part of a series of articles on |

| Arianism |

|---|

| History and theology |

| Arian leaders |

| Other Arians |

| Modern semi-Arians |

| Opponents |

|

|

Gothic Christianity refers to the Christian religion of the Goths and sometimes the Gepids, Vandals, and Burgundians, who may have used the translation of the Bible into the Gothic language and shared common doctrines and practices.

The Gothic tribes converted to Christianity sometime between 376 and 390 AD, around the time of the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Gothic Christianity is the earliest instance of the Christianization of a Germanic people, completed more than a century before the baptism of Frankish king Clovis I.

The Gothic Christians were followers of Arianism.[1] Many church members, from simple believers, priests, and monks to bishops, emperors, and members of Rome's imperial family followed this doctrine, as did two Roman emperors, Constantius II and Valens.

After their sack of Rome, the Visigoths moved on to occupy Spain and southern France. Having been driven out of France, the Spanish Goths formally embraced Nicene Christianity at the Third Council of Toledo in 589.

Origins

During the 3rd century, East Germanic people, moving in a southeasterly direction, migrated into the Dacians' territories previously under Sarmatian and Roman control, and the confluence of East Germanic, Sarmatian, Dacian and Roman cultures resulted in the emergence of a new Gothic identity. Part of this identity was adherence to Gothic paganism, the exact nature of which, however, remains uncertain. Jordanes' 6th century Getica claims the chief god of the Goths was Mars. Gothic paganism is a form of Germanic paganism.

Descriptions of Gothic and Vandal warfare appear in Roman records in Late Antiquity. At times these groups warred against or allied with the Roman Empire, the Huns, and various Germanic tribes. In 251 AD, the Gothic army raided the Roman provinces of Moesia and Thrace, defeated and killed the Roman emperor Decius, and took a number of predominantly female captives, many of which were Christian. This is assumed to represent the first lasting contact of the Goths with Christianity.[2]

Conversion

The conversion of the Goths to Christianity was a relatively swift process, facilitated on the one hand by the assimilation of Christian captives into Gothic society,[2] and on the other by a general equation of participation in Roman society with adherence to Christianity.[3] The Homoians in the Danubian provinces played a major role in the conversion of the Goths to Arianism.[4] Within a few generations of their appearance on the borders of the Empire in 238 AD, the conversion of the Goths to Christianity was nearly all-inclusive.

The Christian cross appeared on coins in Gothic Crimea shortly after the Edict of Tolerance was issued by Galerius in 311 AD, and a bishop by the name of Theophilas Gothiae was present at the First Council of Nicaea in 325 AD.[2] However, fighting between Pagan and Christian Goths continued throughout this period, and religious persecutions – echoing the Diocletianic Persecution (302–11 AD) – occurred frequently. The Christian Goths Wereka and Batwin and others were martyred by order of Wingurich ca. 370 AD, and Sabbas the Goth was martyred in c. 372 AD.

Even as late as 406, a Gothic king by the name of Radagaisus led a Pagan invasion of Italy with fierce anti-Christian views.

Bishop Ulfilas

The initial success experienced by the Goths encouraged them to engage in a series of raiding campaigns at the close of the 3rd century, many of which resulted in having numerous captives sent back to Gothic settlements north of the Danube and the Black Sea. Ulfilas, who became bishop of the Goths in 341 AD, was the grandson of one such female Christian captive from Sadagolthina in Cappadocia. He served in this position for the next seven years. In 348, one of the remaining Pagan Gothic kings (reikos) began persecuting the Christian Goths, and he and many other Christian Goths fled to Moesia Secunda in the Roman Empire.[5] He continued to serve as bishop to the Christian Goths in Moesia until his death in 383 AD, according to Philostorgius.

Ulfilas was ordained by Eusebius of Nicomedia, the bishop of Constantinople, in 341 AD. Eusebius was a pupil of Lucian of Antioch and a leading figure of a faction of Christological thought that became known as Arianism, named after his friend and fellow student, Arius.

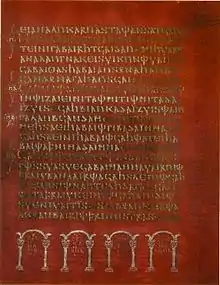

Between 348 and 383, Ulfilas likely presided over the translation of the Bible from Greek into the Gothic language, which was performed by a group of scholars.[5][6] Thus, some Arian Christians in the west used vernacular languages – in this case Gothic – for services, as did many Nicaean Christians in the east. See also: Syriac versions of the Bible and the Coptic Bible), while Nicaean Christians in the west only used Latin, even in areas where Vulgar Latin was not the vernacular. Gothic probably persisted as a liturgical language of the Gothic-Arian church in some places even after its members had come to speak Vulgar Latin as their mother tongue.[7]

Ulfilas' adopted son was Auxentius of Durostorum, and later of Milan.

Later Gothic Christianity

The Gothic churches had close ties to other Arian churches in the Western Roman Empire.[7]

After 493, the Ostrogothic Kingdom included two areas, Italy and much of the Balkans, which had large Arian churches.[7] Arianism had retained some presence among Romans in Italy during the time between its condemnation in the empire and the Ostrogothic conquest.[7] However, since Arianism in Italy was reinforced by the (mostly Arian) Goths coming from the Balkans, the Arian church in Italy had eventually come to call itself "Church of the Goths" by the year 500.

References

- ↑ Goff, Jacques Le (2000-01-01). Medieval Civilization 400–1500. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 9780760716526.

- 1 2 3 Simek, Rudolf (2003). Religion und Mythologie der Germanen. Darmstadt: Wiss. Buchges. ISBN 978-3534169108.

- ↑ Todd, Malcolm (2000). Die Germanen: von den frühen Stammesverbänden zu den Erben des Weströmischen Reiches (2. unveränd. Aufl. ed.). Stuttgart: Theiss. p. 114. ISBN 978-3806213577.

- ↑ Szada, Marta (February 2021). "The Missing Link: The Homoian Church in the Danubian Provinces and Its Role in the Conversion of the Goths". Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum / Journal of Ancient Christianity. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. 24 (3): 549–584. doi:10.1515/zac-2020-0053. eISSN 1612-961X. ISSN 0949-9571. S2CID 231966053.

- 1 2 Heather, Peter; Matthews, John (1991). The Goths in the fourth century (Repr. ed.). Liverpool: Liverpool Univ. Press. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-0853234265.

- ↑ Ratkus, Artūras (2018). "Greek ἀρχιερεύς in Gothic translation: Linguistics and theology at a crossroads". NOWELE. 71 (1): 3–34. doi:10.1075/nowele.00002.rat.

- 1 2 3 4 Amory, Patrick (2003). People and identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554 (1st pbk. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 238, 489–554. ISBN 978-0521526357.