The grotesque body is a concept, or literary trope, put forward by Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin in his study of François Rabelais' work. The essential principle of grotesque realism is degradation, the lowering of all that is abstract, spiritual, noble, and ideal to the material level. Through the use of the grotesque body in his novels, Rabelais related political conflicts to human anatomy. In this way, Rabelais used the concept as "a figure of unruly biological and social exchange".[1]

It is by means of this information that Bakhtin pinpoints two important subtexts: the first is carnival (carnivalesque), and the second is grotesque realism (grotesque body). Thus, in Rabelais and His World Bakhtin studies the interaction between the social and the literary, as well as the meaning of the body.[2]

Carnival

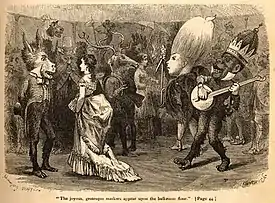

The Carnival, or feast of fools, is a religious celebration where people consume copious amounts of food and wine and have a large party to celebrate. The grotesqueness in the carnival is seen as the abundance and large amount of food consumed by the body. There is much emphasis put on the mouth (where the body can be entered). Eating, drinking, burping from excess, etc. is all done through the mouth. Rabelais uses the Carnival to refer to politics and critique the world based on human anatomy.

In the Italian celebration of Carnival, masks play a major role as many people wear them during the celebration. Many of these masks can be seen as an exaggeration of the grotesque as they feature enlarged facial elements such as an enlarged nose (which is a part of the grotesque body). The Italian celebration of carnival is similar to that of Mardi Gras where food and alcohol are consumed in excess.

Both renditions of Carnival are celebrated immediately before the Christian season of Lent which is about a 40-day season for people of Christian (primarily Catholic) faith to cleanse themselves and become pure before Easter Sunday.

Grotesque realism

Exaggeration, hyperbole, and excessiveness are all key elements of the grotesque style. Certain aspects of the body are referenced when talking about the grotesque. These things include elements of the body that either protrude from the body or an opening part of the body that can be entered. This is because the body in many cases is seen as pure where as the outside world is not. Therefore, parts of the body that allow the outside world in or allow elements inside the body out, are seen and used as an exaggeration of the grotesque. In the article, "Absurdity and Hidden Truth: Cunning Intelligence and Grotesque Body Images as Manifestations of the Trickster", Koepping refers back to Bakhtin's statement, "The themes of cursing and of laughter are almost exclusively a subject of the grotesqueness of the body."[3]

Italian satirist Daniele Luttazzi explained: "satire exhibits the grotesque body, which is dominated by the primary needs (eating, drinking, defecating, urinating, sex) to celebrate the victory of life: the social and the corporeal are joyfully joint in something indivisible, universal and beneficial".[4]

Bakhtin explained how the grotesque body is a celebration of the cycle of life: the grotesque body is a comic figure of profound ambivalence: its positive meaning is linked to birth and renewal and its negative meaning is linked to death and decay.[5] In Rabelais' epoch (1500–1800) "it was appropriate to ridicule the king and clergy, to use dung and urine to degrade; this was not to just mock, it was to unleash what Bakhtin saw as the people's power, to renew and regenerate the entire social system. It was the power of the people's festive-carnival, a way to turn the official spectacle inside-out and upside down, just for a while; long enough to make an impression on the participating official stratum. With the advent of modernity (science, technology, industrial revolution), the mechanistic overtook the organic, and the officialdom no longer came to join in festive-carnival. The bodily lower stratum of humor dualized from the upper stratum."[6]

Early uses of grotesque

Before people began to develop literature or art, leaders would sit in their halls surrounded by their warriors amusing themselves by mocking their opponents and enemies. The warriors would laugh at any weakness or defect, either physical or mental, giving nicknames which exaggerated these traits.[7]

Soon warriors sought to give a more permanent form to their ridicule, which led to rude depictions on bare rocks, or any other surface that was convenient.[7]

In the Medieval Grotesque Carnival, emphasis is put on the nether regions of the body as the center and creation of meaning. The spirit rather than coming from above comes from the belly, buttocks, and genitals.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ "Perforations: Grotesque Corpus". Retrieved 2019-07-12.

- ↑ Clark, Katerina and Michael Holquist 297-299, Mikhail Bakhtin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984.

- ↑ Koepping, Klaus-Peter (February 1985). "Absurdity and Hidden Truth: Cunning Intelligence and Grotesque Body Images as Manifestations of the Trickster". History of Religions. University of Chicago Press. 24 (3): 191–214. doi:10.1086/462997. JSTOR 1062254. S2CID 162313598.

- ↑ "Se Dio avesse voluto che credessimo in lui, sarebbe esistito (in Italian)". Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- ↑ "Brazen Brides Grotesque Daughters Treacherous Mothers by Felicity Collins (Bakhtin, 308-317)". Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- ↑ Boje, David M. (March 2004). "Grotesque Method" (PDF). Proceedings of First International Co-sponsored Conference, Research Methods Division, Academy of Management: Crossing Frontiers in Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods. 2: 1085–1114.

- 1 2 Wright, Thomas (1865). A History of Caricature and Grotesque in Literature and Art. London: Virtue Brothers & CO. pp. 2.

- ↑ Lübker, Henrik. "The Method of In-between in the Grotesque and the Works of Leif Lage." Continent. N.p., Mar. 2012. Web. 22 Oct. 2015

Bibliography

- Clark, Katerina, and Michael Holquist. Mikhail Bakhtin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World [1941]. Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

- The series in the original French is entitled La Vie de Gargantua et de Pantagruel. Available English translations include The Complete Works of François Rabelais by Donald M. Frame and Five Books of the Lives, Heroic Deeds and Sayings of Gargantua and Pantagruel, translated by Sir Thomas Urquhart and Pierre Antoine Motteux.

- Se Dio avesse voluto che credessimo in lui, sarebbe esistito. Daniele Luttazzi, 15 November 2006, danieleluttazzi.it

- Miller, Paul Allen (Fall 1998). "The Bodily Grotesque in Roman Satire: Images of Sterility". Arethusa. 31 (3): 257–283. doi:10.1353/are.1998.0017. S2CID 161905466., coh.arizonaedu

- Christenson, David (Feb–Mar 2001). "Grotesque Realism in Plautus' "Amphitruo"". The Classical Journal. 96 (3): 243–260. JSTOR 3298322. Archived from the original on 2010-04-19. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- Boje, David M. (March 2004). "Grotesque Method" (PDF). Proceedings of First International Co-sponsored Conference, Research Methods Division, Academy of Management: Crossing Frontiers in Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods. 2: 1085–1114.

- Koepping, Klaus-Peter (February 1985). "Absurdity and Hidden Truth: Cunning Intelligence and Grotesque Body Images as Manifestations of the Trickster". History of Religions. 24 (3): 191–214. doi:10.1086/462997. JSTOR 1062254. S2CID 162313598.

- Fecal Matters in Early Modern Literature and Art: Studies in Scatology. J Persels, R Ganim - 2004, books.google.it p. xiv

- Lübker, Henrik. "The Method of In-between in the Grotesque and the Works of Leif Lage." Continent. N.p., Mar. 2012. Web. 22 Oct. 2015.

- Wright, Thomas. A History of Caricature and Grotesque in Literature and Art. London: Virtue Brothers & CO. 1865 p. 2