Guillaume-Silvestre Delahaye (1734 Rouen - 1802/3 Saint-Domingue) was a French botanist, a botanical illustrator, and a Roman Catholic priest or abbé who became embroiled in the 1791 slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue on the island of Hispaniola.[1]

He was a native of Rouen and at one time had been a deacon in the parish of Church of St Joan of Arc, and had studied law in Caen. His career in service of the Church had faltered when in 1757 he was discovered by Parisian police in bed with a certain Marguerite Desmarais and accused of 'debauchery'. There was no conviction, though, and he was released without any further trouble.[2][3]

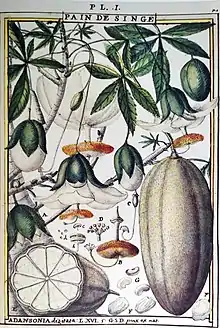

He arrived in Saint-Domingue in 1765, at first serving as 'assistant pastor' at le Cap in Quartier-Morin, and later as the curé of Dondon, where for 23 years he busied himself researching the use of tropical plants, painting and describing them. He made the acquaintance of another French botanist, Palisot de Beauvois, who arrived on the island in 1788, and together they sent at least six shipments of seeds to André Thouin. He published two botanical treatises in Cap-Francais, one in 1781 and the other in 1789. The Cercle des Philadelphes decided in March 1788 to publish Delahaye's work 'Florindie , ou Histoire physico-économique des végétaux de la Torride' by subscription and accordingly printed a four-page prospectus, which proposed a two-volume illustrated natural history of Saint-Domingue at 66 livres per volume. The manuscript was sent to France to have the plates engraved under the supervision of the botanist Antoine Laurent de Jussieu. However, the French Revolution intervened and the project was never completed. Had the book been published as planned it would have been one of the earliest and most significant contributions to colonial botany.[4]

In 1791 the slave uprisings began, and Delahaye became an outspoken critic of the system, publishing his views in 'Feuille du Jour'. At one stage he prematurely announced the abolition of slavery in Saint-Domingue, causing consternation among the slave owners. Despite being arrested by Jeannot Bullet, one of the insurgent leaders, Delahaye was treated with courtesy and his counsel was actively sought. Delahaye himself owned some slaves, and it became evident that the reasons for insurrection were not necessarily about abolition alone, but embodied a wide range of grievances.

There are conflicting accounts of Delahaye's death - one version holding that he drowned or was drowned at le Cap in 1803, while Adolphe Cabon (1873-1961), the Haiti historian, felt that he was killed by the rebels in 1802 for fear that he might betray them. A third view is that he was killed by the black insurgents during a massacre of French whites in July 1793.

References

- ↑ 'The Priest and the Prophetess' by Terry Rey

- ↑ 'La Chasteté Du Clergé Dévoilée: Ou Procès-Verbaux' - vol. 1 (1790)

- ↑ https://journalboutillon.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Le-boutillon-de-la-M%C3%A9rine-n%C2%B0-30.pdf

- ↑ 'Colonialism and Science' - James E. McClellan III (University of Chicago Press, 1992)