| Hartlebury Castle | |

|---|---|

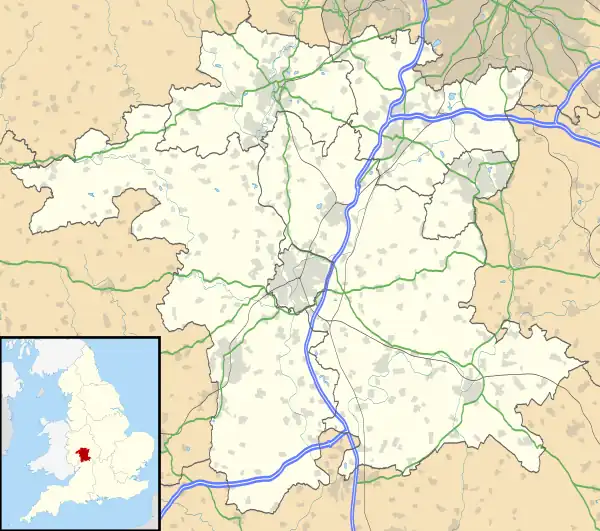

| Worcestershire, England | |

The exterior of Hartlebury Castle from the front | |

Hartlebury Castle | |

| Coordinates | 52°20′19″N 2°14′32″W / 52.3386°N 2.2421°W |

| Grid reference | grid reference SO836712 |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | Yes |

Hartlebury Castle, a Grade I listed building,[1] near Hartlebury in Worcestershire, central England, was built in the mid-13th century as a fortified manor house, on manorial land earlier given to the Bishop of Worcester by King Burgred of Mercia.[2][3] It lies near Stourport-on-Severn in an area with several large manors and country houses, including Witley Court, Astley Hall, Pool House, Areley Hall and Hartlebury and Abberley Hall. Later, it became the bishop's principal residence.[4]

History

Hartlebury Castle was the residence of the Bishop of Worcester from the early 13th century until 2007.

Bishop Walter de Cantilupe, a supporter of Simon de Montfort, began to fortify the Castle, which was embattled and finished by his successor, Godfrey Giffard, in 1268. The gatehouse was added in the reign of Henry VI, by Bishop Carpenter.[5]

King Edward I became Hartlebury Castle's first royal visitor in 1282, when he was on the way to Wales.[6] Queen Elizabeth stayed on 12 August 1575 with the Bishop Nicholas Bullingham, while on a journey to Worcester.[7]

In 1582, Bishop John Whitgift signed the paper that allowed William Shakespeare to marry Anne Hathaway.[8]

In 1646, during the First English Civil War, Hartlebury Castle was strongly fortified and held for King Charles I by Captain Sandys and Lord Windsor, with 120 foot soldiers and 20 horse (cavalry troopers), and provisions for twelve months. However, when summoned by Colonel Thomas Morgan for Parliament, it surrendered in two days without a shot being fired.[5] The Castle was slighted,[3] and the Parliamentary Commissioners seized it and the manor estate, which were sold to Thomas Westrowe for £3,133 6s. 8d. They were returned to the Bishop of Worcester after the Restoration of 1660.[5] The remains of the Civil War-era bastion ditch were first identified from cropmarks in July 2022, and were excavated in 2023. The ditch was found to be 3.4m deep, and produced 17th-century finds including a coin of James I and lead pistol shot.[9]

The Hurd Library was built by Bishop Hurd in 1782 and still contains his extensive collection of books, including works from the libraries of Alexander Pope and William Warburton. Among them is the copy of the Iliad from which Pope's translation was made.

Bishop Hurd was visited by King George III, Queen Charlotte, three of the princesses and the Duke of York in 1788.[10]

The avenue of limes in the park was planted by Bishop Stillingfleet. Bishop Pepys presented Queen Victoria with the herd of deer kept at Hartlebury since time immemorial.[5] An idea of how a bishop's family lived in the mid-19th century can be gained from the vivid diary of ten-year-old Emily Pepys, daughter of Bishop Pepys, which covers a six-month period in 1844–1845.[11]

By 1890 some of the Castle moats had been filled and laid out as flower gardens.[5]

In the First World War, Hartlebury Castle became a Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) Hospital. There are scrapbooks left by soldiers who were cared for at the Castle, available to see online or onsite.

With the coming of Bishop Inge in 2008, the Bishop's residence was moved from the Castle to a house adjacent to the Cathedral in the city of Worcester. In 1964, the north wing was taken over by Worcestershire County Council and in 1966 opened to the public as Worcestershire County Museum.

In 2010, BBC Midlands News reported that Hartlebury Castle was up for sale and local people were running a campaign to stop it falling into private hands. Hartlebury Castle Preservation Trust (HCPT), a registered charity,[12] was formed to preserve Hartlebury Castle for education and public enjoyment and allow the Hurd Library to remain intact there.

Campaigners were given until April 2011 to raise £2 million to prevent the house being put on the open market. It was reported on 17 August 2012 that HCPT had agreed to pay its owners, the Church of England, £2.45 million for the freehold of the buildings, gardens and parks. Moves to raise the purchase price from the Heritage Lottery Fund and from private donors were in progress.[13]

In April 2013 HCPT was successful in its initial Heritage Lottery funding application. This provided funds to develop a Business Plan for the future of Hartlebury Castle. In October 2014 HCPT, with partners Worcestershire County Council and Museums Worcestershire, gained £5M from the Heritage Lottery Fund to preserve it, along with its estate and assets, including the Hurd Library.

In March 2015 HCPT bought Hartlebury Castle and its 43-acre estate, intending to turn it into a visitor attraction with accessible state rooms and a County Museum. In May 2016 a virtual reality tour of the Hurd Library was devised.[14]

In April 2018 renovations were completed and the Castle opened to visitors. The Bishops Palace can be explored with audio guides, talking portraits and interactive displays. The grounds are open with a nature trail. There is a Worcestershire County Museum and a café.[15] The Castle relies on the income from ticket sales, shop purchases and donations to remain open and continue to share its history with the public.[16] The Castle has received financial aid from The National Lottery Heritage Fund, Historic England and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport in the form of the Culture Recovery Fund, given to heritage attractions during the lull in visitors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hartlebury Castle today

Hartlebury Castle Preservation Trust was able to purchase the Castle in 2015 with the help of a £5m grant from The Lottery Heritage Fund and renovation began.[17] A concept was developed to tell its story through the Pepys family, with digital portraits, an audio-guide and interactive displays of its history.[18] The Nature Trail takes visitors round the grounds and the Moat Walk, past a sunken garden, orchard terrace, boardwalk and carriage circle.[19] The café is open all day.[20] The adjacent Worcestershire County Museum has been located on the site for over 50 years. The intention is to make the Castle financially self-sufficient.[21] The Castle can also be privately hired.[22]

Worcestershire County Museum

The Worcestershire County Museum in the former servants' quarters of Hartlebury Castle focuses on local history, toys, archaeology, costumes, crafts by the Bromsgrove Guild, local industry and transportation, area geology and natural history. There are period room displays including a schoolroom, nursery and scullery, and Victorian, Georgian and Civil War rooms.

The grounds include a cider mill and a Transport Gallery that features a fire engine, a hansom cab, bicycles, carts and a collection of Gypsy caravans.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Hartlebury Castle, Hartlebury". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 16 September 2011. (The listing text provides a full architectural description).

- ↑ Hooke 1990, p. 101.

- 1 2 Worcestershire Council staff 2010.

- ↑ Willis-Bund 1913, pp. 380–387.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burton 1890, p. 201.

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "HISTORY". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ↑ John Nichols, Progresses of Queen Elizabeth, vol. 1 (London, 1823), pp. 533 and 536.

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "HISTORY". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ↑ Cornah, Tim (2023). "Civil War archaeology at Hartlebury Castle". Worcestershire Recorder. 108: 7.

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "HISTORY". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ↑ Avery 1984, "Introduction".

- ↑ &subId=0 "HARTLEBURY CASTLE PRESERVATION TRUST, registered charity no. 1127871". Charity Commission for England and Wales.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ BBC News, 17 August 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ↑ Hurd Library VR Tour

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "ABOUT US". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "ABOUT US". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "ABOUT US". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "WHAT TO SEE". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "The Grounds". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "PLAN YOUR VISIT". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "PLAN YOUR VISIT". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ↑ Broadway, Beth. "ABOUT US". Hartlebury Castle. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

References

- Avery, Gillian (1984). "Introduction". The Journal of Emily Pepys. London: Prospect Books. ISBN 0-907325-24-6.

- Willis-Bund, John William (1913). "Parishes: Hartlebury". The Victoria History of the County of Worcester. Vol. 3. pp. 380–387.

- Hooke, D. (1990). Worcestershire Anglo-Saxon Charter-bounds. Woodbridge: Boydell. p. 101.

- Worcestershire Council staff (23 February 2010). "A Brief History of Hartlebury Castle". Worcestershire County Council. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- Attribution

- Burton, John Richard (1890). A history of Kidderminster, with short accounts of some neighbouring parishes. London: E. Stock. p. 201.