| |

| Date | 1 September 1946 – 6 June 1958 (11 years, 9 months and 5 days) |

|---|---|

| Location | Hawaiian Islands |

| Participants | People

Parties Other |

| Outcome |

|

The Hawaii Democratic Revolution of 1954 is a popular term for the territorial elections of 1954 in which the long dominance of the Hawaii Republican Party in the legislature came to an abrupt end, replaced by the Democratic Party of Hawaii which has remained dominant since.[1] The shift was preceded by general strikes, protests, and other acts of civil disobedience that took place in the Hawaiian Archipelago. The strikes by the Isles' labor workers demanded similar pay and benefits to their Mainland counterparts. The strikes also crippled the power of the sugarcane plantations and the Big Five Oligopoly over their workers.

Prelude

Hawaii had a dominant-party system since the 1887 revolution. The 1887 Bayonet Constitution took most of the power away from the monarchy and allowed the Republican Party to dominate the legislature. Besides a brief change of power to the Home Rule Party following annexation, the Republicans had run the Territory of Hawaii. The industrialist Republicans formed a powerful sugar oligarchy, the Big Five.

Illustrative of the prominence of industrialists in the political and social life of the territory was the controversial trial of Grace Fortescue for the murder of Joseph Kahahawai. Following her conviction territorial governor Lawrence M. Judd commuted her 10-year sentence for manslaughter to one hour. Many felt the trial was a failure of justice from political forces. Among the unhappy residents of Hawaii was John A. Burns, a police officer during the trial.[2] Burns founded a movement by collecting support from the impoverished sugar plantation workers. He also restored strength to the divided and weak Democratic Party of Hawaii.

ILWU

The Hilo Longshoremen led by Jack Kawano began unified strikes in the 1930s. The Hilo Longshoremen merged with the ILWU, and Jack Wayne Hall was sent to Hawaii. Among these unified strikes was the disastrous 1938 strike in Hilo against the Inter-Island Steamship Company. During World War II striking was put on hold as the members dedicated their efforts towards the war. In 1944 the ILWU and Communist Party of Hawaii put their support behind the Democratic Party since it became apparent that Burns and his movement wanted to empower the working class. This meeting in 1944 has been considered the beginning of the movement. The movement became known as the "Burns Machine".[3] Burns admitted in 1975 that Communist Party members in the ILWU provided vital experience in maintaining secrecy and organizing support among labor workers while keeping the early movement underground.[4]

After the overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy by a group of foreign and local residents, the members were not restrained in industrializing the Islands, forming plantations and the Big Five. Economic inequality increased, largely caused by the hyper-concentration of wealth among the planters. On the plantations earlier strikes had failed, as when an ethnic camp went on strike the other ethnic groups' camps acted as strikebreakers; the traditional example was the Japanese and Filipino camps' rivalry. The next generation of workers were children of the immigrant workers, born in Hawaii: Niseis, were a major demographic factor in favor of the movement. Many immigrant workers were denied citizenship but could live and work in the islands under contract. The children of these workers who were born in Hawaii automatically became citizens and at this time they began to come of age to be registered voters and could express their dissatisfaction with their votes.[5] They also had gone to school with children from the other ethnic camps and sometimes intermarried them, and therefore did not express the strong ethnic rivalries that their parents had. After the meeting in 1944, Jack Hall began organizing these plantation workers in a strike campaign known as the March Inland for better working conditions and pay.

After the war, Burns was able to gain support from Japanese American veterans of the 100th and 442nd returning home.[6] He encouraged the veterans to become educated under the G.I. Bill and to run for public office. Daniel Inouye, who would become a very prominent US senator, was one first of the veterans he recruited and became a prominent member of the movement.

March Inland

Hall and Kawano's strikes resumed after the war. The ILWU helped to organize the plantation workers spreading unionization from the sea to the land. The successful campaign boosted the union's Hawaiian membership to a sizable 25,000 by the decade's end.[7] This allowed the movement to organize general strikes in the sugar industry and pineapple industry, not just strikes at the docks. The Hawaiian sugar strike of 1946 was launched against the Hawaiian Sugar Planters' Association and the Big Five leaving the cane fields derelict. The 1947 Pineapple Strike followed on Lanai but ended in failure and was tried again in 1951. The 1949 Hawaiian Dock Strike froze shipping in Hawaii for 177 days, ended with the territorial Dock Seizure Act.[8]

Native Hawaiians

Native Hawaiians were on both sides of the Revolution; they were at the time in a social limbo in having less power and rights than residents of European descent but more than residents of East Asian descent. Older Native Hawaiians tended to fear the change would further decline their status, while youths embraced the prospect of gain by ousting the status quo.

House Un-American Activities Committee

As the movement developed the more communist components began to show through. The strikes were increasingly politicized and at the 1949 strike the White Republican aristocracy who were owners in the Big Five became concerned over the communist trend by workers.[9] On October 7, after the 1949 dock strike that year, the territorial legislature requested the House Un-American Activities Committee to investigate the strikes that had become frequent in the territory.[10] On August 28, 1951, the FBI rounded up seven members of the movement[11] including Jack Wayne Hall, Charles Fujimoto (chairman of the Communist Party of Hawaii), and Koji Ariyoshi (editor of the Honolulu Record), who had also published pro-communist work. The Hawaii 7 were charged under the Smith Act for conspiring to overthrow the government; all were released by 1958.

Political elections and reforms

In the 1950 Democratic Convention John A. Burns was elected chairman of the convention and decided that the Party was ready for a strong push at the 1950 elections. But with its progress, the party was dividing into two factions: the right-wing "Walkout" who opposed Burns and the left-wing "Standpat" members who supported Burns. Among the Standpats was John H. Wilson, the founder of the Democratic Party of Hawaii himself, although he did not always agree with Burns, allied with him.[12] With the fracture of the conservative members, the party began to slide farther leftward. Burns wished to re-establish the party ideology as Center-Left. He had Party members sign an affidavit pledging their loyalty to the Democratic Party and not the Communist Party, to deflect communist criticisms and keep the far left in check.[13] During this time communists refrained from discussing their ideology.[14] The rivalry between the two halves of the Democratic Party lead to several defeats in the elections against the Republicans.[15]

Leading up to the 1954 elections the Walkout faction had collapsed into smaller factions proving no threat to the Standpat faction, who effectively took over the party. During the 1954 territorial elections, the Democrats took 22 seats in the territorial House of Representatives, an increase of 11, while the Republicans had just eight out of 30 total. In the territorial Senate, Democrats likewise won a majority of nine out of fifteen, in increase of two from the previous legislature.

The Democrats began to reform the government installing a progressive tax, land reform, environmental protections, comprehensive health insurance plan and expanded collective bargaining.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Republican Samuel Wilder King as governor. King acted as an obstructionist by using the veto 71 times during his administration. Burns commented that during these times the Democrats were more focused on building the Democratic government rather than running it. Following Statehood, Burns – who, until then, had lost his elections – was elected Governor of Hawaii. The strike campaign by the ILWU continued until 1958 when another large sugar strike called the Aloha Strike took place from February 1 to June 6 and ended the campaign.[16]

Statehood

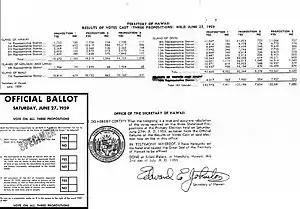

Statehood for Hawaii failed to gain much support in Congress until 1953 when the United States House of Representatives passed a statehood bill (which did not become law). Burns attempted to collaborate with Alaska, which was also pressing to become a state.[17] Burns came under scrutiny by anti-communist Southern Democrats over the role of the Communist Party.[18] Another factor against statehood was a strong possibility of a non-white senator and their opposition to racial segregation.[19] Back in Hawaii, 93% of the population voted in support of statehood. When Pub. L. 86–3, was enacted March 18, 1959, and took effect August 21, the State of Hawaii was established.

Notable Individuals

- John A. Burns: Leader of the movement

- John H. Wilson: Founder of the Democratic Party of Hawaii.

- Daniel Inouye: Later senior United States senator from Hawaii and president pro tempore of the United States Senate.

- William S. Richardson: Later chief justice of the Hawaii Supreme Court

- George R Ariyoshi: Later governor of Hawaii.

- Thomas Gill: Later lieutenant governor and 1st district congressman.

- Spark Matsunaga: Later 1st district congressman and U.S. senator.

- Patsy Mink: Later 2nd district congresswoman

- Koji Ariyoshi: Editor of the Honolulu Record, and one of the Hawaii 7.

- Frank M. Davis: Columnist for the Honolulu Record and poet.

Ernest Murai: Head of US Customs, US Democratic Party Committeman, Member the Honolulu Police Commission.

See also

References

- ↑ Nakamura 2020

- ↑ Stannard 2006, p. 415

- ↑ Niiya 1993, p. 415

- ↑ Boylan & Holmes 2000, p. 104

- ↑ Cooper & Daws 1990, p. 4

- ↑ Boylan & Holmes 2000, p. 66

- ↑ "ILWU locals map - Mapping American Social Movements". depts.washington.edu. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ↑ Holmes 1994, p. 148

- ↑ Holmes 1994, p. 142

- ↑ Holmes 1994, p. 150

- ↑ Holmes 1994, p. 190

- ↑ Boylan & Holmes 2000, p. 114

- ↑ Boylan & Holmes 2000, p. 96

- ↑ Holmes 1994, p. 215

- ↑ Boylan & Holmes 2000, p. 98

- ↑ Beechert 1985, p. 329

- ↑ Whitehead, John S. Completing the Union: Alaska, Hawai’i, and the Battle for Statehood. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2004

- ↑ Holmes, Michael T. The Specter of Communism in Hawaii, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994; p. 175 et passim

- ↑ Bowers, J.D. “The State of Hawaii” in The Uniting States, Shearer, Benjamin F., ed. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004; pp. 294-319

Bibliography

- Arnesen, Eric (2006), Encyclopedia of US Labor and Working Class History, Taylor & Francis, Inc., ISBN 978-0-415-96826-3

- Beechert, Edward D. (1985), Working in Hawaii: A Labor History, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-0890-8

- Boylan, Dan; Holmes, T. Michael (2000), John A. Burns, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2277-4

- Cooper, George; Daws, Gavan (1990), Land and power in Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press, p. 4, ISBN 978-0-8248-1303-1

- Holmes, Michael (1994), The specter of Communism in Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1550-9

- Nakamura, Kelli (2020), Revolution of 1954, Densho Encyclopedia

- Niiya, Brian (1993), Japanese American history, Facts on File Inc., ISBN 978-0-8160-2680-7

- Stannard, David E. (2006), Honor Killing, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-303663-0

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Hawaii |

|---|

| Topics |