He Yan | |

|---|---|

| 何晏 | |

| Secretary of Personnel (吏部尚書) | |

| In office c. 240s – 5 February 249 | |

| Monarch | Cao Fang |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 195 Nanyang, Henan |

| Died | 9 February 249[lower-alpha 1] Luoyang, Henan |

| Spouse | Princess Jinxiang |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Occupation | Philosopher, politician |

| Courtesy name | Pingshu (平叔) |

He Yan (c. 195 – 9 February 249),[lower-alpha 1] courtesy name Pingshu, was a Chinese philosopher and politician of the state of Cao Wei in the Three Kingdoms period of China. He was a grandson of He Jin, a general and regent of the Eastern Han dynasty. His father, He Xian, died early, so his mother, Lady Yin, remarried the warlord Cao Cao. He Yan thus grew up as Cao Cao's stepson. He gained a reputation for intelligence and scholarship at an early age, but he was unpopular and criticised for being arrogant and dissolute. He was rejected for government positions by both emperors Cao Pi and Cao Rui, but became a minister during the rule of Cao Shuang. When the Sima family took control of the government in a coup d'état in 249, he was executed along with all the other officials loyal to Cao Shuang.

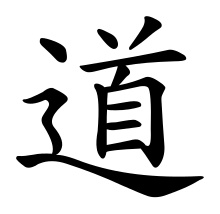

He Yan was, along with Wang Bi, one of the founders of the Daoist school of Xuanxue. He synthesised the philosophical schools of Daoism and Confucianism, believing that the two schools complemented each other. He wrote a famous commentary on the Daode Jing that was influential in his time, but no copies have survived. His commentary on the Analects was considered standard and authoritative for nearly 1000 years, until his interpretation was displaced by the commentary of Zhu Xi in the 14th century.

Life

He Yan was born in Nanyang, Henan.[2] His great-grandfather was a butcher, and his grandfather, He Jin, was a general and regent of the Eastern Han dynasty. His grandaunt was Empress He, the wife of Emperor Ling of the Eastern Han dynasty.[3][4] He Yan's father, He Xian (何咸), died at an early age.[2] The He family's political power was destroyed when a warlord, Dong Zhuo, occupied the Han capital of Luoyang. He Yan's mother escaped and gave birth to He Yan in exile.[5]

When He Yan was about six, his mother was taken as a concubine by the warlord Cao Cao, after which she became known as "Lady Yin". After being adopted by Cao Cao, He was raised with the other princes of Wei, including Cao Cao's eventual successor, Cao Pi (r. 220-226). Cao Pi resented He for acting as if he were a crown prince, and referred to him by the name "false son" rather than his real name. He later married one of Cao Cao's daughters, Princess Jinxiang, who may have been one of He's half-sisters.[6] As a result of his adoption, He Yan spent a considerable amount of time with Cao Cao during his childhood.[7]

At a young age, He Yan gained a reputation of being extremely gifted: "bright and intelligent as a god".[8] He had a passion for reading and study. Cao Cao consulted with him when he was confused about how to interpret Sun Tzu's The Art of War, and was impressed with He Yan's interpretation.[7] He Yan's contemporaries (both in Cao Wei and the Jin dynasty) disliked him, and wrote that he was effeminate, fond of makeup, dissolute and egotistical. The second Wei emperor Cao Rui (r. 226-239) refused to employ him because he believed that He was a "floating flower": well known for a life of flamboyance and dissipation. He was reportedly fond of "five-mineral powder", a hallucinatory drug.[8]

He Yan was not able to achieve political prominence either under Cao Pi or Cao Rui. When Cao Rui died in 239, he left his adopted son, Cao Fang, then still a child, on the throne. Cao Shuang, a relative of the Cao family, took control of the government as regent. He Yan ingratiated himself into Cao Shuang's inner circle, eventually being promoted to Secretary of Personnel (吏部尚書) and bringing many of his friends and acquaintances into important positions. One of He Yan's friends promoted into office during this period was the influential philosopher Wang Bi.[8]

Death

He Yan retained control of most official appointments until 249, when the Sima family took control of the government in a coup d'état. After taking control of the government, the Sima family executed Cao Shuang and all members of his faction, including He Yan.[8]

According to the Chronicles of the Clans of Wei, Sima Yi assigned He Yan the task of presiding as a judge in the trial of Cao Shuang. He Yan, who wanted to be acquitted, judged Cao Shuang very harshly in order to gain Sima Yi's favour, but Sima Yi added He Yan's name to the list of criminals to be executed at the last moment.

At the time of He Yan's death, he had a five-year-old son whom Sima Yi dispatched soldiers to arrest. Before the soldiers arrived, He Yan's mother, Lady Yin, who was still alive, hid her grandson and threw herself at Sima Yi's mercy at the palace. She eventually convinced Sima Yi to pardon her grandson, and He Yan's son survived.

Philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

According to the Wei dynastic histories, He Yan enjoyed and had a great insight into the works of the Daoist philosophers Laozi and Zhuangzi, and into the Book of Changes, from an early age. He wrote a famous commentary that was influential in his own time, the Commentary on the Daode Jing (Daode Lun), but no copies have survived. He was planning on writing a more detailed, interlinear commentary on the Daode Jing; but, after comparing his draft with a similar draft by a younger Wang Bi, He decided that his interpretation was inferior, and the Commentary that he eventually produced was more general and broad.[9]

He Yan was a member of a committee that produced an influential and authoritative commentary on Confucian theory, the Collected Explanations of the Analects (Lunyu Jijie), which collected, selected, summarised and rationalised the most insightful of all preceding commentaries on the Analects that had been written by his time. He produced the commentary as a member of a five-member committee (the other four members of the committee were Sun Yong, Zheng Chong, Cao Xi and Sun Yi), but was given almost sole credit as the principal writer by subsequent Chinese scholars, and by the Tang dynasty (618-907) He Yan's name was the sole author associated with the Collected Explanations. Modern scholars are unsure of what evidence led medieval Chinese scholars to believe that He was the sole author, or if he wrote the Collected Explanations out of interest or because he was ordered to by the Wei court, but continue to credit He Yan as the principal author out of convention. After He Yan presented it to the imperial court, the Collected Explanations was quickly recognised as authoritative and remained the principal text used by Chinese readers to interpret the Analects for nearly 1,000 years, until it was displaced by Zhu Xi's commentary in the 14th century.[10]

He Yan believed that Daoism and Confucianism complimented each other so that by studying them both in a correct manner a scholar could arrive at a single, unified truth. Arguing for the ultimate compatibility of Daoist and Confucian teachings, He argued that "Laozi [in fact] was in agreement with the Sage" (sic).[11] By promoting the synthesis of Daoist and Confucian concepts, He became a principal advocate of the neo-Daoist school of Xuanxue (along with his friend and contemporary, Wang Bi).[12] As a scholar of Xuanxue, He was notable for exploring the theory of wuwei.[13] He was a prolific writer of poetry and wrote numerous miscellaneous essays on philosophy, politics, literature, and history, some of which still survive.[14]

Notes

- 1 2 Cao Fang's biography in the Sanguozhi recorded that Cao Shuang and his associates – Ding Mi (丁謐), Deng Yang, He Yan, Bi Gui, Li Sheng and Huan Fan – were executed along with their extended families on the wuxu day of the 1st month of the 1st year of the Jiaping era of Cao Fang's reign.[1] This date corresponds to 9 February 249 in the Gregorian calendar.

References

- ↑ ([嘉平元年春正月]戊戌,有司奏収黃門張當付廷尉,考實其辭,爽與謀不軌。又尚書丁謐、鄧颺、何晏、司隷校尉畢軌、荊州刺史李勝、大司農桓範皆與爽通姦謀,夷三族。) Sanguozhi vol. 4.

- 1 2 三国志 一晋 陈寿 著 栗平夫 武彰 译 中华书局 P2-52 魏帝纪第一, 三国手册 逸安 著 中国古籍出版社 P186-191,曹操大事年表

- ↑ Gardner 10

- ↑ 闲云野鹤王定璋 著 四川教育出版社 P129

- ↑ 魏末传“晏妇金乡公主, 即晏同母妹.”

- ↑ Gardner 10-11

- 1 2 Fang Shiming, (2006).方诗铭论三国人物 上海古籍出版社 P225-226 ISBN 7-5325-4485-0

- 1 2 3 4 Gardner 11

- ↑ Gardner 13

- ↑ Gardner 8-10, 15, 17

- ↑ Gardner 13-14

- ↑ 闲云野鹤王定璋 著 四川教育出版社 P129-130

- ↑ 闲云野鹤王定璋 著 四川教育出版社 P130-133, 魏晋玄学新论徐斌 著 上海古籍出版社 P122-124,128-135

- ↑ 何晏著述考高华平, 文献 (季刊)2003年10月第4期, Page69-80

Bibliography

- Chen, Shou (3rd century). Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi).

- Gardner, Daniel K (2003). Zhu Xi's Reading of the Analects: Canon, Commentary, and the Classical Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12865-0.

- Pei, Songzhi (5th century). Annotations to Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi zhu).