Health in Norway, with its early history of poverty and infectious diseases along with famines and epidemics, was poor for most of the population at least into the 1800s. The country eventually changed from a peasant society to an industrial one and established a public health system in 1860. Due to the high life expectancy at birth, the low under five mortality rate and the fertility rate in Norway, it is fair to say that the overall health status in the country is generally good.

Population data

Norway has a birth-, death-, cancer-, and population register, which enables the authorities to have an overview of the health situation in Norway. The total population in Norway as of 2018, was 5,295,619.[1] The life expectancy at birth was 81 years for males and 84 years for females (2016).[1] The under five mortality per 1000 live births in 2016 were three cases and the probability of dying between 15 and 60 years for males was 66 and 42 for females per 1000 in population.[1] The total expenditure on health per capita was $6,347 in 2014. Total expenditure on health as percentage of GDP was 9,7% [1] Gross national income per capita was $81,807 (2018).[2]

Fertility

The total fertility rate per women in 2018 was 1,62, while the regional average was 1,6 and global average was 2,44.[3] Prevalence of tuberculosis was 10 per 100 000 in population and the regional average was 56 while global average was 169.[4] In Norway today, there are 5371 HIV positive people, 3618 men and 1753 women. In 2008 the incidence of HIV positive people had a peak and the highest incidence of HIV positive. Since that, there have been a decrease in new cases.[5]

Human Development Index

Norway was awarded first place according to the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) for 2018 .[6]

A new measure of expected human capital calculated for 195 countries from 1990 to 2016 and defined for each birth cohort as the expected years lived from age 20 to 64 years and adjusted for educational attainment, learning or education quality, and functional health status was published by the Lancet in September 2018. Norway had the seventh highest level of expected human capital with 25 health, education, and learning-adjusted expected years lived between age 20 and 64 years.[7]

Demographic measures for Norway:[1][2][3][4]

| Total population (2018) | 5,295,619 |

| Gross national income per capita (PPP international $, 2018) | 81,807 |

| Life expectancy at birth m/f (years, 2017) | 81/84 |

| Probability of dying before the age of five (per 1 000 live births, 2017) | 3 |

| Probability of dying between 15 and 60 years m/f (per 1 000 population, 2016) | 66/42 |

| Total expenditure on health per capita (Intl $, 2014) | 6,347 |

| Total expenditure on health as % of GDP (2014) | 9.7 |

History

In the early Norway faced major challenges. The differences between rich and poor were large, living conditions poor and infant mortality high. Economic conditions in the country improved, but some social groups still lived under constrained conditions. The nutritional status was poor as well as hygiene and living conditions. The conditions and class differences were worse in the cities than in the countryside.[8]

Immunization against smallpox was introduced in the first decade of the 19th century. In 1855, Gaustad Hospital opened as the first mental asylum in the country and was the start of an expansion in treating people with such disorders.[8] After 1900 living standards and health conditions improved and the nutritional status improved as poverty decreased. Improvement in public health occurred during development in several areas such as social and living conditions, changes in disease and medical outbreaks, establishment of the health care system and emphasis on public health matters. Vaccination and increased treatment opportunities with antibiotics resulted in great improvements. Average income increased as did improvements in hygiene. Nutrition became better and more effective also improving general health.

In the 1900s the situation improved in Norway and, as a result of decreased poverty, nutritional status improved. Within 100 years Norway became a wealthy nation. Even though Norway experienced a setback during World War II, the country achieved steady development. Improved hygiene led to fewer infectious diseases and scientific discoveries led to breakthroughs in many fields including health.[8]

However, an economic downturn in the 1920s exacerbated the nutritional situation within the country. Nutrition therefore became an important part of social policies.[9] In periods there were high rates of unemployment, and poverty affected women and children most. Children often had to walk long distances to get work as shepherds during the summer in order to help their families with income. In mining towns as Røros, children also had to work in the mines.[8] Living conditions improved during the 1900s. From being a poor country, Norway developed within 100 years to become a wealthy nation. Even though the country experienced a setback under the Second World War, the country achieved steady development. From 1975 Norway was self-sufficient in petroleum products and oil became an important part of the Norwegian economy. Improved hygiene led to fewer infectious diseases and scientific discoveries led to breakthroughs in many fields including health.[8]

After 1945, smoking became a relevant factor. While infectious diseases decreased, chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease were blooming.[8] From 2000, life expectancy was still on the increase. There are, however, still social differences when it comes to health. While globalization increases the demand for infectious control and knowledge, the Norwegian population demands more from the government in regard to health and treatment.[8]

Infant mortality

Early on, there were no statistics kept for the whole country on infant mortality, but in Asker and Bærum in 1809 infant mortality was 40 percent for all live births.[10] In 1900, infant mortality was higher in Norway than in any other European country. Development of the welfare state has contributed to a great decrease in infant mortality rates. This can be attributed to better nutrition and living conditions, better education and economy, better treatment possibilities and preventive health care (especially immunization).[8] The infant mortality rate increased again between the 1970 and 1980 due to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). SIDS was unknown from earlier, but the increase was dramatic. The trend was reversed when Norwegian parents were encouraged to lay their children on their backs and not their stomachs when sleeping.[8]

Population

At the beginning of the 19th century the total population was just under 1 million, however it doubled within the next hundred years even though many decided to emigrate. Industrialization resulted in many people emigrating from the countryside to the major cities for work.[8] At the beginning of the 1900s the population was 2.2 million and increased to about 4.5 million through the 1900s. 15 percent of the country's population lived in Oslo and Akershus. The proportion of people associated with agriculture, forestry and fishing declined while the percentage affiliated with industries increased.[8]

Communicable diseases

The Norwegian government recognized that the population needed to improve its health if the country was to become a nation with strong economic development.[11]

- Cholera and typhoid fever were common communicable diseases in the 1800s. Norway experienced several epidemics; cholera was the worst. The last epidemic outbreaks were around the 1840s. Even though these were not as severe as the Black Death in the 1300s, mortality rates were high.[8]

- Sexually transmitted diseases also caused widespread problems. These were, however, not defined and divided into gonorrhea and syphilis until later.[8]

- Smallpox was the most serious disease in the years around 1800; legislation for vaccination against smallpox was introduced in 1810. At first, the law was not strictly enforced but when people were commanded to show their vaccination cards at confirmations and weddings, there was an increase in the vaccinating of children and Norway finally gained some control over this disease.[8]

- Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, ravaged the west coast of Norway. Patients were isolated in leprosy hospitals with room for up to 1000 patients. Gerhard Armauer Hansen (1841-1912), working in Bergen, discovered the leprosy bacillus. He revealed the association between hospitalization for infected patients and a decrease in the number of new cases.[12][13]

- Tuberculosis caused many deaths in the late 1800s while leprosy rates declined. Mortality of tuberculosis was high around 1900, but decreased steadily for the next fifty years. The greatest decrease in tuberculosis happened before vaccinations and medical treatments were available; the decrease was caused by improved living conditions, nutrition, and hygiene.[8]

- The Spanish flu of 1918 affected the country. This influenza pandemic took many lives, especially those of young people who lacked immunity to the new flu virus.[8]

- Diphtheria, a common childhood disease, raged during the early years of World War II, but with new vaccines available, the country experienced an immediate positive response.[8]

- Polio had its last major outbreak in 1951 when 2100 cases were registered.[14] In 1956 immunization of polio started.[8]

Discovery of microbes

In the late 1800s microbes were discovered and prevention of diseases were now possible. Until now, spreading of infections had only been debated. With new discoveries within the field and greater understanding on how bacteria and viruses transfer and spread among humans it was possible to make significant changes in treatment and care of patients. One example was to isolate people with leprosy and tuberculosis in order to stop spreading.[15]

Antibiotics

In the 1900s many vaccines were developed and the first antibiotic, penicillin, came about in the 1940s. These introductions were very powerful tools in preventing and treatment of childhood diseases.[8]

Vaccines

More vaccines became available and the child-vaccination-program was growing rapidly. Almost all feared childhood diseases were going extinct. Vaccines against measles (rubella) were introduced to the childhood immunization program in 1978. Rubella is dangerous to the fetus if the mother is affected during pregnancy. Today, all children are offered free vaccines and the offer is voluntary. The coverage for most vaccines is high.[8]

HIV/AIDS

In the early 1980s AIDS came as an unknown disease. Norway was early in preventing it in high-risk groups, through information campaigns. The HIV virus was later discovered and HIV tests became available from 1985.[8]

Cardiovascular diseases

Incidences of tuberculosis became fewer and an increase in cases and mortality of chronic diseases appeared, especially cardiovascular disease. Tobacco is one of the most important causes of cardiovascular and cancer diseases. During World War 2, the tobacco use in Norway was limited because of strict rationing. After the war, sale of tobacco bloomed and so did the implications from consuming it.[8] In the late 1900s, chronic diseases were dominating and because of increased life expectancy, people lived longer with these chronic diseases. Around millennium new treatment and prevention for cardiovascular diseases ensured a decrease in mortality, however, these diseases are still one of the greatest public challenges in the country.[8] The incidence of coronary heart disease in Norway reduced significantly between 1995 and 2010, with about 66% of the reduction due to changes in modifiable risk factors like activity levels, blood pressure, and cholesterol. Mortality reduced from 137 per 100,000 person-years to 65.[16]

Lifestyle diseases

Lifestyle diseases are a new concept from the second half of the 1900s. Tobacco use and increases in cholesterol levels show a strong correlation to higher risk of cardiovascular disease.[8]

Mental health

Mental health services are part of the Norwegian special health care services. In some cases this includes involuntary mental health treatment.[17] The four regional health service institutions, owned by the state, receive fixed economic support from the state budget. They are responsible for special health services including mental health care in hospitals, institutions, district mental health centers, child and adolescent mental health services and nursing homes.[18]

In addition to providing treatment, the mental health care services provide research, education for health personnel, and follow-up of patients and their relatives.[18]

There are different sectors within the mental health services. District mental health centers are responsible for general mental health service. They have outpatient facilities, inpatient facilities and emergency teams. Patients can be referred to the district mental health center by a general practitioner for diagnosing, treatment or admission.[19]

There are specialized centers, ideally at central hospitals, for children and adolescents, the elderly, and severe cases such as drug addiction, personality disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders etc.[19] Normally people who are discharged from treatment at central hospitals are referred to the district mental health centers for follow-up and treatment. Treatment can consist of psychotherapy with or without medications. Physical treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy, are used for specific disorders. Treatment usually starts at the hospital, with the aim of continuing treatment at home or at the district mental health center.[19]

Children and adolescents

Child and adolescent mental health outpatient facilities offer mental health care for children and adolescents between 0–17 years of age. Central child and adolescent mental health service is aimed at challenges which cannot be handled in the regional state facilities, such as the general practitioner, school nurse, school, outreach services for youth and child services. The child and adolescent mental health services work closely with psychologists, child psychiatrists, family therapists, neurologists, social workers etc. Their aim is to diagnose and treat psychiatric disorders, behavioral disorders and learning disorders in close collaboration with care givers.[20] For patients below the age of 16, parents must consent to admission.[20][21]

Involuntary care

Involuntary mental health care in Norway is divided into inpatient and outpatient facilities and observation.[21] In involuntary inpatient facilities patients can be held against their will, and can be picked up by the police if needed.[21] In involuntary outpatient services the patient lives at home or is voluntarily in an institution, but regularly has to report to the district mental health center. These patients cannot be held against their will, but can be picked up by the police in the case of missed appointments.[21] For involuntary observation in hospital a person can be held for up to ten days, or in some cases for twenty days, in order for the hospital to decide whether the criteria for involuntary mental health care are met.[21] The control committee has as their main task to ensure that every patient's rights are secured and protected in a meeting with involuntary care.[22]

Financing

Mental health services are financed through needs-based basic funding to the regional health services, outpatient clinic refunding, deductibles and ear-marked grants from the state budget. Rates for outpatient work are partly based on hours worked and partly based on procedures; there are rates for diagnosing, treatment and follow-up per telephone or in collaborative meetings. In addition patients pay a deductible for outpatient consultations.[18]

Burden of disease

A survey done in 2011 showed that 10.2% of the population of Norway reported to have experienced symptoms of anxiety and depression within the last two weeks.[23] The lifetime prevalence of severe depression is estimated to be 15.6%. Treatment and social services for the mentally ill cost society about 70 million Norwegian kroner (more than 10 million US dollars) yearly.[24]

Current health status

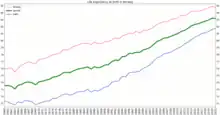

Life expectancy and death

The report, 2016 shows that life expectancy has increased by five years, from 76.8 years in 1990 to 81.4 years in 2013. The reduction in deaths from cardiovascular disease is the main reason for this increase. Life expectancy in Norway in 2017, was 84.3 years in women and 80.9 years in men.[25] From 2007 to 2017, life expectancy increased by 2.7 years for men, but only by 1.6 year for women. This can be explained, for example, by different "smoking careers" for men and women.[26]

Public Health Report 05/2018, shows that the two main causes of death are cardiovascular disease and cancer. The mortality rate of cardiovascular disease has fallen significantly over the past 50 years, and deaths have been largely pushed to age groups over 80 years. In younger age groups, the number of deaths is low.

Annually, between 550 and 600 die of suicide, about half past 50 years of age. Compared to other countries, there are relatively many who die of drug-fatal deaths, an average of 260 per year.

Deaths due to traffic accidents have fallen considerably, the average number of death last 5 years is 138, serious injuries 678.[27]

Unhealthy diet

One of the major findings from the report (2016), is that an unhealthy diet is the most important risk factor for premature deaths in Norway.

“46 per cent of all deaths before the age of 70 in Norway can be explained by behavioural factors such as unhealthy diet, obesity, low physical activity and the use of alcohol, tobacco and drugs” says Professor Stein Emil Vollset, Director of the newly established Centre for Burden of Disease at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

“If we consider the population as a whole, it appears that an unhealthy diet represents a greater risk to public health than smoking. This is not because an unhealthy diet is more dangerous than smoking but because fewer Norwegians now smoke. Since 1990, the percentage of smokers in Norway has decreased from 35 per cent to 13 per cent”, explains Vollset.

By addressing these risk factors, much of Norway’s disease burden could be reduced. Up to 100,000 years of life could be saved if Norwegians ate healthier diets.

Approximately 1 in 4 middle-aged men and 1 in 5 women have obesity with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher in Norway. Among children, the proportion with overweight and obesity appears to have stabilised.[28]

Drug overdose and suicide

Drug overdose and suicide rates are high. Among the under-49 age group, suicide and drug overdoses are the main causes of death in Norway, with the highest rates among the Nordic countries (Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Finland and Sweden).

The report shows that lower back pain, neck pain, anxiety and depression are among the main causes of poor health among the Norwegian population as a whole, while heart disease and cancer claim most lives.

Diseases of affluence

A wealthy economy makes it possible to buy tobacco, fast food, sweets and sugary drinks that few people had access to or could afford until after 1950. These days many people have desk jobs, cars, and less demanding housework. In large, physical activity is decreasing, electronics, computers, social media, and the internet demands more of daily life. Drugs have also become more available in society. ‘New living conditions’ such as these give rise to new challenges for public health.[30] Only 30 percent of adults in Norway are fulfilling the advice to stay physically active for 150 minutes per week.[31]

Tobacco

The number of people smoking in Norway has fallen equally for both men and women since 2000. 11% of the adult population in Norway smoke on a daily basis while 8% are occasional smokers. Daily smoking is most common for the population with low educational attainment. Over the last two decades, efforts to reduce the population’s exposure to tobacco smoke combined with increased awareness of the health risks of smoking appear to be having an impact. For example, early death from tobacco smoke fell 28% between 1990 and 2013.[32]

In Norway 2017, 11 per cent was daily smokers, in 2007, it was 22 per cent daily smokers.[33]

The use of snus has during the same period become more common among the population. 12% of the population daily use snus and 4% are occasional snus users.[34]

Non-communicable diseases

The main causes of reduced health and disability in Norway are cardiovascular diseases, cancer, mental health and musculoskeletal disorders.[34]

Annually, 70,000 people are treated for cardiovascular diseases. Technological progress and development within medical treatment have since the 1970s had huge impact on survival of diseases, especially cardiovascular disease.[34]

Anxiety and depression are the most prevalent of mental disease. 6% of the population under 75 years takes antidepressants.[34]

Other communicable diseases such as COPD, diabetes and dementia also weights heavily on the burden of disease. As the life expectancy is increasing, more people are living longer with chronic diseases. As of that the prescription of drug consumption is high.[34]

Social differences in health

The living standard of the Norwegian population has increased, though there are still differences between educational groups. Those with higher education and economy have generally the best health status and live 5–6 years longer than those with lower educational attainment.[34] New public health legislation (Folkehelseloven) came into play in 2012, and the purpose of this act is to contribute to a society that promotes public health and evens out social inequalities in health.[30]

Disease Burden

DALYs in Norway 1990 - 2019

.png.webp)

Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) is a measure of the burden of disease and an indicator of health status. It is described as "the sum of years lost due to premature death and years lived with disability".[35] The burden of disease is divided into three categories, non-communicable diseases; injuries, including violence and self-harm; communicable, neonatal, maternal and nutritional diseases.[36]

In Norway, the DALYs per percent has been dominated by Non-communicable diseases, NCDs, as displayed in Fig 1 (blue). Ischemic heart disease (IHD) has the highest share with 6.35% of total DALYs. IHD has remained as the leading cause of DALYs in both 1990 and 2019, although its prevalence has been decreasing. Back pain has the second largest share of 4.7% of total DALYs, followed by COPD and stroke that both have 3.92% of total DALYs. As shown in the table below, the DALYs lost by strokes have decreased in 2019.[37]

Injuries, including violence and self harm has led to the second most share of total DALYs. Falls have the largest share within this area with 3.99% of total DALYs and has been slightly increasing. This is followed by self-harm with 1.77% and road injuries with 0.9 of total DALYs, both decreasing.[37]

Communicable, neonatal, maternal and nutritional diseases have the smallest share of the total DALYs. The primary cause within this area is lower respiratory infections with 1.47% of total DALYs. Lower respiratory infections was one of the top ten causes of DALYs in 1990. However, it no longer remains in the top ten as its prevalence has decreased throughout the years. The neonatal disorders with 0.85% of total DALYs have also been decreasing, while diarrheal diseases are increasing with 0.58% of total DALYs. Within this group it is protein energy malnutrition that has the highest annual increase of 2.41% with total DALYs of 0.33%.[37]

| 1990 | 2019 |

|---|---|

| 1 Ischemic heart disease | 1 Ischemic heart disease |

| 2 Stroke | 2 Low back pain |

| 3 Low back pain | 3 Falls |

| 4 Falls | 4 COPD |

| 5 Lung cancer | 5 Stroke |

| 6 Lower respiratory infections | 6 Lung cancer |

| 7 Self-harm | 7 Diabetes |

| 8 Colorectal cancer | 8 Headache disorders |

| 9 Headache disorders | 9 Colorectal cancer |

| 10 Anxiety disorders | 10 Anxiety disorders |

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Statistisk Sentralbyrå (2019). "Key figures for the population". Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- 1 2 Worldbank (2018). "GDP per capita". Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- 1 2 Worldbank (2018). "Fertility rate". Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- 1 2 World Health Organisation (2018). "Norway Statistics". Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-05. Retrieved 2014-09-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ United Nations Development Program (2018). "Human Development Reports". Archived from the original on 2018-11-18. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- ↑ Lim, Stephen; et, al (2018). "Measuring human capital: a systematic analysis of 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016". Lancet. 392 (10154): 1217–1234. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31941-X. PMC 7845481. PMID 30266414.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Nordhagen, R; Major, E; Tverdal, A; Irgens, L; Graff-Iversen, S (2014). "Folkehelse i Norge 1814 - 2014". Folkehelseinstituttet. Retrieved 2014-09-02.

- ↑ Nordby, T (2009). "Helsedirektør Evangs planer for velferdsstaten". Michael. 6: 331–7.

- ↑ Fure E. Spedbarnsdødeligheten i Asker og Bærum på 1700- og 1800 tallet. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 2005; 125: 3468-71.

- ↑ Moseng, OG (2003). Ansvaret for undersåttenes helse (1603-1850). Universitetsforlaget.

- ↑ Irgens, LM (1980). "Leprosy in Norway. An Epidemiological Study Based on a National Patient Registry". Lepr Rev. 51: i–xi, 1–130. PMID 7432082.

- ↑ Irgens, LM (1984). "The Discovery of Mycobacterium Leprae. A Medical Achievement in the Light of Evolving Scientific Methods". Am J Dermatopathol. 6 (4): 337–343. doi:10.1097/00000372-198408000-00008. PMID 6388392.

- ↑ Flugsrud, LB (2006). "50 år med poliovaksine i Norge". Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen. 126: 3251.

- ↑ "Folkehelse i Norge 1814 - 2014". Folkehelseinstituttet (in Norwegian Bokmål). 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

[Det kom] lovpålegg om smitteisolasjon, slik som for eksempel ved lepra i 1877 og tuberkulose i 1900.

- ↑ "Tromsø Study Documents Dramatic Decline in CHD in Norway". Medscape. 23 November 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ↑ Psykisk helsevern

- 1 2 3 Helsedirektoratet (2014). "Psykisk helsevern i spesialhelsetjenesten". Retrieved 2014-09-02.

- 1 2 3 Distriktspsykiatrisk senter

- 1 2 Barne- og ungdomspsykiatri

- 1 2 3 4 5 Helsedirektoratet (2014). "Tvungent psykisk helsevern". Retrieved 2014-09-02.

- ↑ Helsedirektoratet (2014). "Kontrollkommisjonen". Retrieved 2014-09-02.

- ↑ Folkehelseinstituttet (2014). "Psykiske plager - et betydelig folkehelseproblem". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-09-02.

- ↑ Norsk Psykologforening (2014). "Fakta om psykisk helse". Archived from the original on 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2014-09-02.

- ↑ "PUBLIC HEALTH REPORT - SHORT TERM Health condition in Norway 2018" (PDF).

- ↑ "PUBLIC HEALTH REPORT - SHORT TERM Health condition in Norway 2018" (PDF).

- ↑ "2018-05-29". ssb.no (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ↑ "Overweight and obesity in Norway". Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ↑ "Norway: State of the Nation's Health Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2016" (PDF).

- 1 2 Norwegian Institute of Public Health (2018). "Folkehelse i Norge 1814-2014". Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- ↑ Norwegian Institute of Public Health (2018). "Fysisk aktivitet i Norge" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- ↑ "Norway: State of the Nation's Health Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2016" (PDF).

- ↑ "2018-01-18". ssb.no. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Norwegian Institute of Public Health (2018). "Public Health Report - Short Version 2018" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- ↑ Skolnik, Richard (2019). Global Health 101 (Fourth ed.). p. 34. ISBN 9781284145380.

- ↑ Roser, Max; Ritchie, Hannah (2016-01-25). "Burden of Disease". Our World in Data.

- 1 2 3 "GBD Compare | IHME Viz Hub". vizhub.healthdata.org. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- Owe, KM., Mykletun, A., Nystad, W., Forsen, L. Fysisk aktivitet - Folkehelserapporten 2014. Folkehelseinstituttet. 2014. Available from: http://www.fhi.no/artikler/?id=110551 Sited 2014-09-03.

- WHO. Countries: Norway. World Health Organization. 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/countries/nor/en/ Sited 2014-08-31.

- WHO. Norway: Health profile. World Health Organization. 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/countries/nor.pdf?ua=1 Sited 2014-08-31.