Helene Minkin | |

|---|---|

העלענע מינקין | |

Helene Minkin, 1907 | |

| Born | June 10, 1873 |

| Died | February 3, 1954 (aged 80) |

| Resting place | Mount Hebron Cemetery |

| Years active | 1886–1932 |

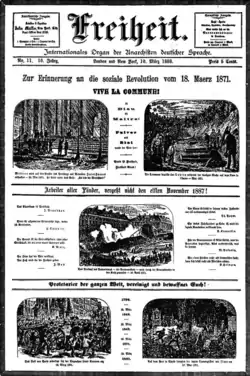

| Title | Editor of Freiheit |

| Term | 1905–1907 |

| Predecessor | Johann Most |

| Successor | Max Baginski |

| Movement | Anarchism |

| Spouse | Johann Most |

Helene Minkin (June 10, 1873 – February 3, 1954) was a Russian-Jewish anarchist immigrant who settled in New York City and had close ties with three of the U.S. anarchist movement's most notable figures – Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, and Johann Most – Minkin's common-law husband.

Working closely with Most, Minkin contributed to the German anarchist paper Freiheit, and took over editorial responsibilities during her husband's many incarcerations as well as after his death in 1906.[1] She later went on to write her memoirs, which were later translated and published as a collection, Storm in My Heart: Memories from the Widow of Johann Most, which provides her personal perspective of her and Most's lives, as well as a close look into the conditions of late 19th- and early 20th-century immigrant life in the United States.[2]

Biography

Early life

Minkin was born to a poor Jewish family in Grodno - a predominantly Jewish shtetl - the same part of Western Russia as Goldman and Berkman.[3] Grodno, now a part of modern-day Belarus, was a part of the Pale of Settlement, the segregated territory within which Jewish citizens were required to reside.[3] During this time, the Jewish population was routinely subjected to repression, including legal, social, and spatial restrictions.[4] After her mother's death in 1883, Helene and her sister Anna went to live with their grandparents in Bialystok, just outside of Poland.[5] Here, it is likely that Helene was first exposed to radical ideologies by being exposed to socialist literature while being tutored by local students.[6] Likely due to continued religious persecution, Helene (16), Anna (17), and her father Isaac Minkin (35) decided to emigrate to the United States in 1888 among the first wave of Eastern European immigrants from Russia; they boarded the Wieland on May 20 in Hamburg, and began the long journey to New York.[6]

Joining the anarchist movement in New York

The 19th century was a time of political and social turmoil, which provided further incentives for immigration to the U.S., with the promise of religious and political freedom.[7] New York City became the central hub for immigrants from Europe, and consequently, the city experienced an explosion of radical political movement.[8] Historian Tom Goyens argues that the Lower East Side of NY, the home of Minkin for the extent of her political career, is one of the most significant locations in radical political history.[7] At the turn of the century, the anarchist movement in the states was dominated by German immigrants, with a growing influx of Jewish members.[9] Many of these increasingly popular ideologies - such as anarchism, communism, and democratic socialism - arose from and influenced socialist and Marxist schools of thought, building off of the same enlightenment ideals of autonomy and political idealism that lead to the French and American revolutions.[10] However, anarchism was viewed extremely negatively by the larger public, and was viewed as contradictory to American values - making it a risky ideological choice.[11] Though particular stances and tactics varied, the anarchist ideologies that spread during this time, including those of Minkin, all held a core principle that rejected any form of coercive authority - particularly that of the state.[1] Historian Paul Buhle argued that if anarchists hadn't contributed to the beginnings of the labor movement, worker rights gains within the country could have been delayed for another generation.[12]

Ideas, alcohol, and discontent flourished in saloons which became designated meeting places for radicals, such as the infamous Sach's Saloon, a favorite of Jewish anarchists.[13] It was in Sach's that Minkin was engaged in the uproar caused by the Haymarket Affair in 1886 - violence had erupted in an anarchist rally against police brutality of demonstrators and strikers in support of the eight hour work day.[13] Seven anarchists allegedly connected to the violence, though there was no evidence to support their guilt, were sentenced to death as a result.[13] Though devastating in the eyes of anarchists, the publicity around the Haymarket affair pulled new Jewish immigrants like Minkin towards the movement.[13] In her memoirs, Minkin describes this as a huge blow to her confidence in her new home and its promise of freedom, and was likely the catalyst that grew her passive interest in radical politics to active participation.[14]

Friendship with Emma Goldman

Another driving force behind Minkin's growing interest in anarchism was her roommate and friend Emma Goldman, who lived in the Minkin home for a brief period along with Helene, Isaac Minkin, and Anna Minkin.[15] Goldman was also a Jewish immigrant from Russia who had emigrated just two years earlier.[13] Helene and Emma both worked in the poor conditions of New York garment factories - an occupation popular among female Jewish immigrants.[13] However, Goldman was not like Minkin in all respects - in contrast to the platform of the German anarchist circles the two frequented, Goldman was particularly interested in a feminist perspective.[16] She criticized the anarchist movements’ marginalization of women within its leadership circles with pointed comments directed towards Johann Most, with whom she had a brief intimate relationship and is credited with launching her political career.[16] Though Most had the intention of continuing the relationship, Goldman claimed that she was convinced otherwise due to his domestic intentions for her.[17]

It was exactly this point of contention that would lead to her disillusionment from not only Most, but Minkin as well. Minkin and Most's relationship was a popular topic within the German anarchist movement in New York, and Goldman took part in the critique. In a letter to her comrade and sought after lover, Alex Berkman, Goldman describes Helene and Anna Minkin as “common ordinary women” who willingly limit their lives to domestic servitude, as she explains in her memoirs, Living my Life.[18] In addition to her criticisms, Goldman took more direct action against Most when a disagreement over Berkman's assassination attempt on Henry Frick lead her to horsewhip him in 1892 at Jewish anarchist meeting.[19] Goldman and Berkman were eventually forced out of New York anarchist circles when they were both deported to Russia in 1919 because of their political beliefs.[20]

Relationship with Johann Most and family life

Johann Most and Minkin met in 1888, and the movement leader, twenty-six years her senior, made an impression on her - but due to the harsh opinions fostered by Goldman, a close friendship wasn't formed until 1892.[21] Though there is no official marriage record, Minkin often referred to Most as her husband and used the Most surname, so it is likely the two engaged in a common-law marriage the following summer.[21] The marriage was widely criticized by Most's comrades, who ironically enough had families of their own, but worried that their leader would become softened by family ties.[22] Minkin also describes friction within their marriage, but credits their shared political beliefs with keeping them content.[22] Despite the marital turbulence and criticism from their comrades, Minkin and Most had two sons: John Jr. Most, born May 18, 1894, and Lucifer Most, born July 22, 1895.[23]

Life after Most's death

Shortly after Most's death in 1906, Minkin – who had taken as over as editor of Freiheit once again – decided to finally let the paper go under, insisting that it was nothing without the contributions of her late husband.[24] This gave weight to previous accusations made within anarchist circles that Most maintained a totalitarian like grip on the paper.[24] Other radical press groups of the time, such as those behind one of the many competing periodicals Amerikanische Arbeiter-Zeitung (American worker's newspaper), questioned hierarchical positions such as editor.[25] Despite Minkin's resistance, other anarchist leaders insisted upon continuing Freiheit's publication and formed the Freiheit Publishing Association - with the intention operating the paper through a collective.[25]

The accusations and other rumors about Most lead Minkin to reject the financial support offered to her to support herself and her children, and she soon withdrew from the anarchists completely.[24] How Minkin spent her later years after is somewhat unclear, as she stepped out of the spotlight after Most's death. She mostly distanced herself from her old life, changing residences and occupations often, and sometimes going by the name Miller or Mueller.[26] However, she still considered it her responsibility to clear Most's name and continue his legacy by publishing the fourth volume of his memoirs and later her own in 1932.[27] Despite her constant relocation, upon Minkin's death at age eighty on February 3, 1954, she was back in the Bronx, New York.[28] Her grave is located in Flushing, New York, at the Mount Hebron Cemetery.[24]

Works

Freiheit

Though Minkin's involvement in Freiheit began with mundane tasks under Most's supervision, Minkin became instrumental in its survival as the controversial paper would often lead to Most's imprisonment, which would have - without Minkin - become leaderless.[24] After becoming involved in the Socialist Party in Germany, Most was imprisoned, as he had been before, for his political views and eventually forced to leave his home country.[29] Most relocated to London, where he would begin publishing Die Freiheit (later known simply as Freiheit), as means to promote his special brand of radical politics, which within a few years shifted from slightly left of his former party associate, Karl Marx, to what he eventually acknowledged as anarchism.[30] Through Freiheit - which he brought with him from London upon his immigration to the U.S. in 1882 - and his lectures, Most found himself in the center of the growing German anarchist movement in the Lower East Side of New York City - where he would eventually meet Minkin.

The paper was often controversial; encouraging propaganda of the deed or direct political action or taking responsibility for a Frankfurt bombing of a police station.[24] Such claims as well as instructions to build explosives published by Most within Freiheit and in his pamphlet, Science of Revolutionary Warfare,[31] further contributed to the public's generalization of anarchists as violent criminals despite a relatively low body count compared to other radical groups such as white nationalists.[32] This rhetoric once again lead to imprisonment, particularly after the paper once again supported assassination after the death of McKinley at the hands of an anarchist in 1901.[33] When others from their circle failed to step up to maintain Freiheit in Most's absence, Minkin stepped in as editor and manager for two years while he was imprisoned.[33] Without Minkin's contributions and her nurturing of Most's continued political activity, Most would have let the paper fold and his influence wane.[24]

A Storm in My Heart

Helene's intentions of writing her own memoirs were put on the back burner until Goldman's Living my Life painted her, Most, and Anna Minkin in a negative light.[15] In response, Helene began to publish her memoirs in thirteen installments in Foverts (now known as The Forward), the same Yiddish daily paper which had published Goldman's memoirs. Publication ran in installments from September 18, 1932, to December 18, 1932.[34] The memoirs describe her family and political life spanning from her arrival to New York up to a few years after Most's death.[2] She portrays Most as a level-headed and virtuous man, combating Goldman's critical depiction, and emphasizes the influence both had upon her political ideologies.[35] Her memoirs were later translated from Yiddish and published by the AK Press as a collection, Storm in My Heart: Memories from the Widow of Johann Most.[2]

References

- 1 2 Goyens 2007, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 Minkin 2015, pp. 25–132.

- 1 2 Goyens 2015, p. 2.

- ↑ Goyens 2015, p. 3.

- ↑ Goyens 2015, pp. 3–4.

- 1 2 Goyens 2015, p. 4.

- 1 2 Goyens 2007, p. 4.

- ↑ Goyens 2007, p. 15.

- ↑ Goyens 2015, p. 9.

- ↑ Levy 2010, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Madison 1945, p. 60.

- ↑ Buhle 1983, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Goyens 2015, p. 8.

- ↑ Goyens 2015, pp. 4–5.

- 1 2 Minkin 2015, p. 25.

- 1 2 Goyens 2015, p. 11.

- ↑ Goyens 2007, p. 25.

- ↑ Goyens 2015, p. 46.

- ↑ Goyens 2007, p. 22.

- ↑ Goyens 2007, p. 5.

- 1 2 Goyens 2007, p. 24.

- 1 2 Goyens 2015, p. 10.

- ↑ New York, State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1794–1940 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Goyens 2015, p. 15.

- 1 2 Goyens 2007, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Goyens 2015, p. 17.

- ↑ Goyens 2015, p. 16.

- ↑ New York, New York, Death Index, 1949–1965 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2017.

- ↑ Goyens 2015, p. 5.

- ↑ Madison 1945, p. 57.

- ↑ Madison 1945, p. 58.

- ↑ Levy 2010, p. 14.

- 1 2 Goyens 2007, p. 26.

- ↑ Goyens 2015, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Minkin 2015, p. 50.

Bibliography

- Buhle, Paul (Spring 1983). "Anarchism and American Labor". International Labor and Working-Class History. 23 (23): 21–34. doi:10.1017/S0147547900009571. JSTOR 27671439.

- Goyens, Tom (2007). Beer and Revolution: The German Anarchist Movement in New York City, 1880–1914. St. Louis, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252031755. OCLC 77011509.

- Goyens, Tom (2015). "Introduction". Storm in My Heart: Memories from the Widow of Johann Most. Oakland, California: AK Press. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-1849351973. OCLC 875240338.

- Levy, Carl (2010). "Social Histories of Anarchism". Journal for the Study of Radicalism. 4 (2): 1–44. doi:10.1353/jsr.2010.0003. JSTOR 41887657. S2CID 144317650.

- Madison, Charles (January 1945). "Anarchism in the United States". Journal of the History of Ideas. 6 (1): 46–66. doi:10.2307/2707055. JSTOR 2707055.

- Minkin, Helene (2015). Goyens, Tom (ed.). Storm in My Heart: Memories from the Widow of Johann Most. Translated by Braun, Alisa. Oakland, California: AK Press. pp. 25–132. ISBN 978-1849351973. OCLC 875240338.