Herbert Singleton | |

|---|---|

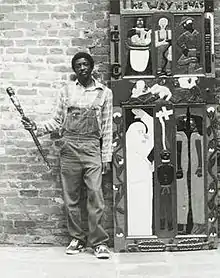

Herbert Singleton and his piece The Way We Was | |

| Born | Herbert Singleton 1945 |

| Died | 2007 (aged 61–62) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Sculpture and Bas Relief |

| Movement | Modern Art |

Herbert Singleton (1945–2007) was an American bas-relief sculptor and painter based in New Orleans, Louisiana. His work documented the tribulations of life in the Algiers neighborhood of New Orleans.

Life and career

Herbert Singleton was born the eldest of eight children on May 31, 1945, to Elizabeth and Herbert Singleton Sr.[1] Singleton recalled that one day when he was ten years old, his father left the house to buy a pack of cigarettes and never returned. His mother supported the family on her single income working at a hospital. He attended school until the seventh grade,[2] although other accounts claim the sixth grade.[3] He worked most of his youth in a steel factory and as a bridge painter. He was arrested as a young adult for various narcotic crimes and spent thirteen years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary between 1967 and 1986. After his release, he began making little clay snake sculptures for the Voodoo Museum in New Orleans in 1970. Distraught by the fragility of unfired clay, Singleton switched his medium to wood and began carving long ax handles into walking sticks, primarily used as weapons.[2] His customers were pimps, drug dealers, and horse-and-carriage drivers in the French Quarter. In fact, one carriage driver notoriously killed a robber during a mugging with one of Singleton's sticks, and thus they became known as "Killer Sticks."[3]

His later work was carved on doors and other solid woods found on the banks of the Mississippi River. It is estimated that Singleton completed over 200 works, although his earliest creations cannot be counted accurately.[2] He lived the rest of his life in Algiers, a New Orleans' neighborhood on the western bank of the Mississippi River. He died at the age of 62.

Subject and materials

Singleton used manual tools such as knives, chisels and mallets to carve his pieces. Most of the wood he used he collected from the levees bordering Mississippi River. He often found oak and cypress doors and cabinets to work with.[4] Reflecting on his artistic process, Singleton said, "When the river was low, I would find a plank of wood to carve. I would look at it and wonder if someone's life fell apart."[5]

He painted his reliefs and carvings with saturated enamel primary colors. His early carvings, "killer sticks," and stools depict intricate scenes of violence, lynchings, drugs, dealing, prostitution, and other every-day scenes from the inner-city of New Orleans. His stylized, dramatic narratives come from personal experience living amidst violent crime, police brutality, and financial instability. In 1980 his sister and two friends were murdered by three white police officers searching for an African American person who shot another white officer. They took Singleton in for questioning, beat, and suffocated him for twelve hours. None of the officers were charged for the murders or cruel punishment.[1]

The art historian and curator Alice Rae Yelen noted a shift in his subject matter mid-career. Once Singleton switched to doors and larger materials, He began to depict biblical scenes, local social situations, and autobiographical subjects.[4] Broadly, Singleton's subject matter can be categorized as either religious scenes, scenes from contemporary African American street life, or socio-political themes from local to international scope.[1]

Exhibitions

Singleton has shown work in the following exhibitions:

- Ten Southern Black Folk Artists. 1990, Icons Gallery, Houston, TX.

- Not by Luck: Self-Taught Artists in the American South. 1993, Hunterdon Art Center, Clinton, NJ.

- Black History and Artistry: Work by Self-Taught Painters and Sculptors from the Blanchard Hill Collection. 5 Feb- 3 Mar, 1993, Baruch College, CUNY, New York, NY.

- Pictured in my Mind: Contemporary American Self-Taugt Art from the collection of Dr. Kurt Gitter and Alice Rae Yellen. 1995, Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, AL.

- By Any Means Necessary: Sculpture by African American Self-Taught Artists. 14 Jan- 13 Feb, 1999, Cavin-Morris Gallery, New York, NY.

- Let it ShineL Self-Taught Art from the T. Marshall Hahn Collection. 23 Jun- 2 Sep, 2001, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA.

- Singular Visions: Folk Art from Charlottesville Collections. 5 Oct- 2 Dec. 2001, University of Virginia Art Museum, Charlottesville, VA.

- Street Savvy: New and Recent Works. 2002, Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning, Jamaica, NY.

- Goin' Cross my Mind: Contemporary Self-Taught Artists of Louisiana. 2002, Madame John's Legacy, New Orleans, LA.

- The Louisiana Purchase Dis-Mantled. Apr-May 2003, Barrister's Gallery, New Orleans, LA.

- Tony Green does Mardi Gras. Feb 2004, John Stinson Fine Arts, New Orleans, LA.

- Coming Home: Self-Taught Artists, the Bible, and the American South. 19 Jun- 13 Nov 2004, Art Museum of University of Memphis, Memphis, TN.

- The Souls of Black Folk: Selections of African American Folk Art from the Museum's Permanent Collection. 28 Nov. 2004- ongoing, Museum of African American Life and Culture, Dallas, TX.

- The Dream Lives On: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Struggle for Justice. Jan- Feb 2005, Robert Cargo Folk Art Gallery, Paoli, PA.

- Amazing Grace: Self-taught Artists from the Mullis Foundation. 29 Sep 2007- 6 Jan, 2008, Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, GA.

- Crossroads: Spirituality in American Folk Traditions. 17 Nov, 2007- 24 Feb, 2008, Owensboro Museum of Fine Art, Owensboro, KY.

- Houston Collects: African American Art. 3 Aug- 26 Oct, 2008, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Houston, TX.

- Go Tell It On the Mountain. 4 Oct 2012- 8 Jun 2013, California African American Museum, Los Angeles, CA.

- Souls Stirring: African American Self-Taught Artists from the South. 3 Oct. 2013- 8 Jun. 2014, California African American Museum, Los Angeles, CA.

- Prospect.3 Notes for Now. 25 Oct 2014- 25 Jan, 2015, Multi-venue, New Orleans, LA.

- What Carried Us Over: Gifts from the Gordon W. Bailey Collection. Sep 13, 2019 - Apr 19, 2020. Pérez Art Museum Miami, FL.[6]

Collections

The following museums have works by Singleton in their permanent collections:

References

- 1 2 3 Pictured in my mind: contemporary American self-taught art from the collection of Dr. Kurt Gitter and Alice Rae Yelen. 1997-03-01.

- 1 2 3 Museum of American Folk Art encyclopedia of twentieth-century American folk art and artists. 1991-05-01.

- 1 2 Conwill, Kinshasha (2001). Testimony: Vernacular Art of the American South. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams Inc. pp. 130–1. ISBN 0-8109-4484-7.

- 1 2 McClanan, Anne L. (1997). "Passionate Visions of the American South Self-Taught Artists from 1940 to the Present (review)". Southern Cultures. 3 (2): 90–95. doi:10.1353/scu.1997.0016. ISSN 1534-1488. S2CID 144739421.

- ↑ Coker, Gylbert Garvin; Arnett, William (2001). "Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South". African American Review. 35 (4): 660. doi:10.2307/2903291. ISSN 1062-4783. JSTOR 2903291.

- ↑ "What Carried Us Over: Gifts from the Gordon W. Bailey Collection • Pérez Art Museum Miami". Pérez Art Museum Miami. Retrieved 2023-09-29.

- ↑ "Hallelujah Door". High Museum of Art. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ↑ "Philadelphia Museum of Art - Collections Object : "Going Home: McDonoghville Cemetery"". www.philamuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ↑ "Herbert Singleton: Inside Out / Outside In | Raw Vision Magazine". rawvision.com. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ↑ "Pérez Art Museum Miami Announces Major Gift from Los Angeles-Based Collector, Scholar, and Advocate Gordon W. Bailey". www.pamm.org. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ↑ "Voodoo/Tree of Life | Birmingham Museum of Art". Retrieved 2019-12-08.