The recorded History of Brunswick, Georgia dates to 1738, when a 1,000-acre (4 km2) plantation was established along the Turtle River. By 1789, the city was recognized by President George Washington as having been one of five original ports of entry for the American colonies. In 1797, Brunswick's prominence was further recognized when it became the county seat of Glynn County, a status it retains to this day. During the later stages of the Civil War, with the approach of the Union Army, much of the city was abandoned and burned. Economic prosperity eventually returned, when a large lumber mill was constructed in the area. By the late 19th-century, despite yellow fever epidemics and occasional hurricanes, business in Brunswick was thriving, due to port business for cotton, lumber, naval stores, and oysters. During this period, Brunswick also enjoyed a tourist trade, stimulated by nearby Jekyll Island, which had become a posh, exclusive getaway for some of the era's most influential people. World War I stimulated ship building activity in Brunswick. But it was not until World War II that the economy boomed, when 16,000 workers were employed to produce ninety-nine Liberty ships and "Knot" ships. During the war, Brunswick's Glynco Naval Air Station was, for a time, the largest blimp base in the world. Since the end of World War II, the city has enjoyed a period of moderate economic activity, centered on its deep natural port, which is the westernmost harbor on the eastern seaboard. In recent years, in recognition of a thriving local enterprise, Brunswick has declared itself to be the "Shrimp Capital of the World".

Early colonization

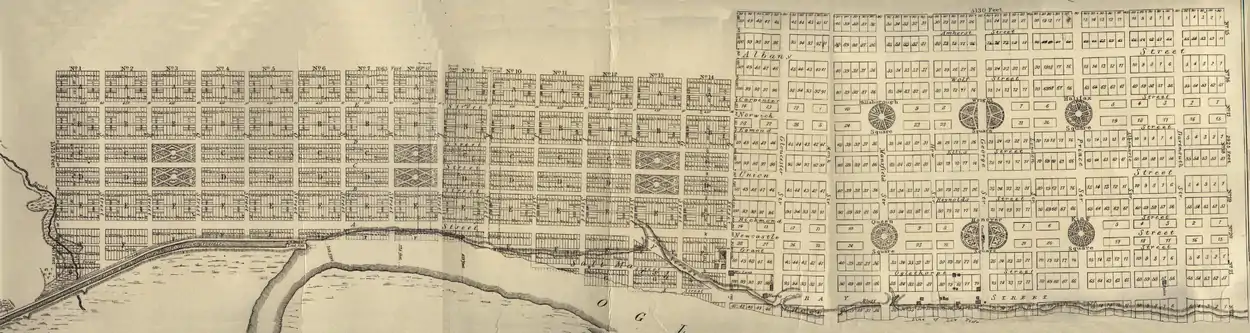

As early as 1738, the area's first English settler, Mark Carr, a captain in General James Oglethorpe's Marine Boat Company, established his 1,000-acre (4 km2) plantation along the Turtle River (at an area known as Plug Point). In 1771, the Royal Province of Georgia purchased Carr's fields and laid out the town of Brunswick in the grid style following Oglethorpe's Savannah Plan. Brunswick obtained its name from the duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg in Germany, the ancestral home of King George II of Great Britain.

In 1789, George Washington proclaimed Brunswick one of the five original ports of entry for the colonies. Because of this notion, the city began to prosper, and in 1797, the Georgia General Assembly in Louisville transferred the county seat of Glynn County from Frederica on St. Simons Island to Brunswick.

Commerce and expansion

Little development occurred in the town during the thirty years after its designation as the county seat. Records show that Glynn Academy, the first public building, was built in 1819; it closed four years later due to lack of attendance. The school soon re-opened, however, and in 1840, a new building was erected on Hillsborough Square, the present location of Glynn Academy. In 1826, the Georgia General Assembly granted title to much of the undeveloped town to Urbanus Dart and William R. Davis. Soon after the title was granted, Brunswick had a courthouse, a jail, and about thirty houses and stores. Along with the founder of the Brunswick and Florida Railroad, Thomas Butler King of St. Simons Island, Dart and Davis formed a company to construct a canal north to the Altamaha River, connecting the natural port with interior plantations.

In 1836, the Oglethorpe House hotel was built; two years later, a newspaper was started and a new bank opened. But the panic of 1837 caused cotton and timber prices to plummet and languished the progress of the canal and railroad projects. The Cotton Crash of 1839 only put the city in further jeopardy.

Following a period of recession, the Brunswick–Altamaha Canal opened in 1854, followed by the railroad in 1856. Brunswick received its second charter that very year and was officially incorporated as a city on February 22, 1856. In 1860, the city had a population of 468, a weekly newspaper, a bank, and a sawmill.

American Civil War

During the Civil War, the Confederate States Army burned the St. Simons Island Lighthouse as they left to keep it from falling into Union hands. In Brunswick, wharves as well as the Oglethorpe House (which would have made an ideal headquarters or hospital for the Union Army) were burned. When the city was ordered to evacuate, most of the citizens fled to nearby Waynesville. The canal and railroad ceased operation, and Brunswick was abandoned.

After suffering from post-war depression into the 1870s, in 1874, one of the nation's largest lumber mills began operation on St. Simons Island, leading to the return of economic prosperity. Canals and rivers gave way to rail traffic as the Brunswick & Albany and Macon & Brunswick railroads connected Georgia to the Port of Brunswick.

Late 19th century

In 1878, poet and native Georgian Sidney Lanier wrote his world-famous poem "The Marshes of Glynn" based on the salt marshes that lie in Glynn County as he sought relief from tuberculosis in Brunswick's climate. The Sidney Lanier Bridge, which spans across the marshes, is named in his honor. There is a historical marker overlooking the marshes of Glynn commemorating Lanier and the poem, and a live oak tree near the marker is named Lanier's Oak.

The December 1888 issue of Harper's Weekly predicted that "Brunswick by the Sea" was destined to become the winter Newport. Jekyll Island had become a posh, exclusive getaway for some of the era's most influential people. Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, Pulitzers, and Goodyears escaped to Brunswick and the Golden Isles to hunt, fish, and mingle. People flocked to the breathtaking Oglethorpe Hotel once it opened its doors in 1888.

In 1893, a yellow fever epidemic compounded the troubles brought by worldwide depression. Two hurricanes, one in 1893 and one in 1898, and their resulting storm surge flooded the city. However, the city quickly recovered because of the ever-expanding port business for cotton, lumber, naval stores, and oysters.

The World Wars

Wooden and concrete ships designed to repel mines were built in Brunswick for World War I. A large gunpowder and munitions plant was built to the northwest of town, but it was not completed before the war ended.

During World War II, German U-boats threatened the coast of Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina. Blimps became a common site as they patrolled the coastal areas. During the war, blimps from Brunswick's Glynco Naval Air Station, at the time the largest blimp base in the world, safely escorted almost 100,000 ships without a single vessel lost to enemy submarines.

Liberty ships

In World War II, Brunswick boomed as over 16,000 workers of the J. A. Jones Construction Company produced ninety-nine Liberty ships and "Knot" ships (Type C1-M ships which were designed for short coastal runs, and most often named for knots) for the U.S. Maritime Commission to transport matériel to the European and Pacific Theatres.

The first ship was the SS James M. Wayne (named after James Moore Wayne), whose keel was laid on July 6, 1942 and was launched on March 13, 1943. The last ship was the SS Coastal Ranger, whose keel was laid on June 7, 1945 and launched on August 25, 1945. The first six ships took 305 to 331 days each to complete, but soon production ramped up and most of the remaining ships were built in about two months, bringing the average down to 89 days each. By November 1943, about four ships were launched per month. The SS William F. Jerman was completed in only 34 days in November and December 1944. Six ships could be under construction in slipways at one time.

In December 1944, the United States Navy requested six ships from each shipyard. The workers guaranteed the delivery of not six, but seven ships. For the first eleven months of 1944, an average of 4.27 ships were launched per month. Up to this point the shipyard had never produced more than five ships in a calendar month, except for August 1944, in which six ships were launched. However, the first ship of August 1944 was launched on August 1 and the last one on August 31, and only three ships had been launched in July and only four ships were launched in September. So a ship that might well have been launched in July was actually launched on August 1. The workers fulfilled their promise of completing seven ships in December 1944 by working overtime, including working on Christmas Day. Apart from the ships launched in December 1944, only one ship was completed in under 43 days. With the extra work, all of the ships launched this month were completed in 34 to 42 days (which included the SS William F. Jerman mentioned above).

Furthermore, the workers asked that they not be paid for their extra work. Each worker endorsed their time-and-a-half paycheck over to the government. They never produced more than five ships in a calendar month again, although a full five ships had been launched in the previous month of November and five more were launched the next month, January 1945. By March 1945 production of ships started to decline. The last ship launched was the SS Coastal Ranger, launched on August 25, 1945, shortly after the war ended.

Most of the Liberty ships from Brunswick were assigned to U.S. shipping companies and most of them were named after famous Americans (starting with U.S. Supreme Court Justices from the South). However, numbers 19, 29, and 31–40 went to Great Britain (Ministry of War Transport) under the Supplemental Defense Appropriations Act of 1941 (see Lend-Lease) and were given one-word names starting with "Sam" (e.g. Samdee). Number 73 went to the Norwegian government.

An iron cut-away scale model (approximately 1:20) of a Liberty ship had been built for employee training. Sometime after the end of World War II this was put on display in Brunswick at the end of F. J. Torras Causeway near the shipyards. It was not maintained, however, and after twenty years it rusted badly and was scrapped. In 1987, efforts began to build and display a new model. This 23-foot (7 m) scale model was unveiled on August 23, 1991 in Mary Ross Park. It is very similar to the original scale model except that it is not cut away to reveal the inner decks. A new park (called Liberty Ship Park) is currently under construction near the site of the original Sidney Lanier Bridge and the model is to be moved there.[1]

1991 plane crash

An Atlantic Southeast Airlines Embraer EMB 120 plane crashed in Brunswick on April 5, 1991 due to propeller control failure.[2] The crash claimed the lives of all twenty-three people on board, including former U.S. Senator John Tower of Texas and astronaut Sonny Carter.

Modern times

Today Brunswick is home to a thriving port, the deepest natural port in the area. As the westernmost harbor on the eastern seaboard, as well as the proclaimed "Shrimp Capital of the World," Brunswick bustles with activity. The city is also home to Hercules, one of the oldest and most important yellow-pine chemical plants in the world. Rich-SeaPak Corporation and King and Prince Seafood are also based in the area. The Georgia Ports Authority Mayor's Point and Marine Point Terminals, as well as the Colonel's Island Bulk Facility attract business from around the world.

Brunswick's Old Town residential and commercial district is the largest small town, urban National Register of Historic Places district in Georgia. Downtown is undergoing a revitalization through the National Main Street Program, preserving and showcasing its distinctive historic structures. Annual events such as the Old Town Tour of Homes, Concerts in the Square, the Brunswick Stewbilee, and HarborFest encourage visitors to discover the charms of Brunswick's parks and gracious homes.

See also

References

- ↑ "Project Oaktree: Liberty Ships". Glynncounty.com. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- ↑ Archived September 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Historical markers in Glynn County

- Liberty ship marker and model

- Master list of Liberty ships

- History of Brunswick

- "Welcome Ships for Victory" Photograph collection at the Brunswick-Glynn County Library that depict World War II cargo ship building activities from 1943 to 1945.

Media related to History of Brunswick, Georgia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Brunswick, Georgia at Wikimedia Commons