| History of Bucharest |

|---|

|

|

| See also |

|

|

The history of Bucharest covers the time from the early settlements on the locality's territory (and that of the surrounding area in Ilfov County) until its modern existence as a city, capital of Wallachia, and present-day capital of Romania.

Wallachia c. 1459–1859 (Ottoman vassal)

United Principalities 1859–1862

Romanian United Principalities 1862-1866

Principality of Romania 1866–1881

Kingdom of Romania 1881-1947

Socialist Republic of Romania 1947-1989

National Salvation Front 1989-1990

Romania 1990-present

Prehistory

The territory of present-day Bucharest has been inhabited since the Palaeolithic. The earliest evidence of human life in this region dates from this period. They include flint tools, found in the area of the Colentina Lake shore, or around the Fundeni Lake. At that time, all this area where now is Bucharest was covered by forests.

Settlements appeared as well later during the Neolithic, along the Dâmbovița and Colentina rivers. The oldest Neolithic dwellings on the territory of the capital have been discovered in the Dudești neighbourhood, at Fundeni and at Roșu. Later archaeological research also revealed later Neolithic settlements, situated at Pantelimon, Cățelu, Bucureștii Noi or at Giulești, or around Bucharest, at Jilava or Vidra.[1] During the Neolithic, Bucharest saw the presence of the Glina culture, and, before the 19th century BC, was included in areas of the Gumelnița culture.[2] During the Bronze Age, a third phase of the Glina culture (centered on pastoralism, partly superimposed on the Gumelnița culture) and, later, on the Tei culture, evolved on Bucharest's soil.[3]

Antiquity

During the Iron Age, the area was inhabited by a population identified with the Getae and the Dacians, who spoke an Indo-European language. The view that the two groups were the same is disputed,[4] while the culture's latter phase can be attributed to the Dacians; small Dacian settlements—such as Herăstrău, Radu Vodă, Dămăroaia, Lacul Tei, Pantelimon, and Popești-Leordeni—were found around Bucharest.[5] These populations had commercial links with the Greek cities and the Romans – ancient-Greek coins were found at Lacul Tei and Herăstrău (together with a large amount of local counterfeit ones), and jewels and coins of Roman origin in Giulești and Lacul Tei.[6]

Bucharest was never under Roman rule, with an exception during Muntenia's brief conquest by the troops of Constantine I in the 330s; coins from the times of Constantine, Valens, and Valentinian I etc. were uncovered at various sites in and around Bucharest.[7] It is assumed that the local population was Romanized after the initial retreat of Roman troops from the region, during the Age of Migrations (see Origin of the Romanians, Romania in the Early Middle Ages).

Foundation

Beginnings

Slavs founded several settlements in the Bucharest region, as pointed out by the Slavic names of Ilfov (from elha – "alder"), Colentina, Snagov, Glina, Chiajna, etc.[8] According to some researches, the Slavic population was already assimilated before the end of the Dark Ages.[9] While maintaining commercial links with the Byzantine Empire (as attested by the excavations of 9th–12th century Byzantine coins at various locations),[10] the area was subject to the successive invasions of Pechenegs and Cumans and conquered by the Mongols during the 1241 invasion of Europe.[11] It was probably later disputed between the Magyars and Second Bulgarian Empire.[12]

According to a legend first attested in the 19th century, the city was founded by a shepherd named Bucur (or, alternatively, a boyar of that same name).[13] Like most of the older cities in Muntenia, its foundation has also been ascribed to the legendary Wallachian prince Radu Negru (in stories first recorded in the 16th century).[14] The theory identifying Bucharest with a "Dâmbovița citadel" and pârcălab mentioned in connection with Vladislav I of Wallachia (in the 1370s)[15] is contradicted by archaeology, which has shown that the area was virtually uninhabited during the 14th century.[16]

Early development

Bucharest was first mentioned on September 20, 1459, as one of the residences of Prince Vlad III Dracula.[17] It soon became the preferred summer residence of the princely court – together with Târgoviște, one of the two capitals of Wallachia – and was viewed by contemporaries as the strongest citadel in its country.[18] In 1476, it was sacked by the Moldavian Prince Stephen the Great, but was nonetheless favoured as a residence by most rulers in the immediately following period[19] and was subject to important changes in landscape under Mircea Ciobanul, who built the palace and church in Curtea Veche (the court's area), equipped the town with a stockade, and took measures to provide Bucharest with fresh water and produce (early 1550s).[20]

When Mircea Ciobanul was deposed by the Ottoman Empire (Wallachia's overlord) in the spring of 1554, Bucharest was ravaged by Janissary troops; violence again occurred after Mircea returned to the throne and attacked those who had been loyal to Pătrașcu the Good (February 1558),[21] during the 1574 conflict between Vintilă and Alexandru II Mircea, and under the rule of Alexandru cel Rău (early 1590s).[22]

17th century

Growth and decline

In tune with the increasing demands of the Ottomans and the growing in importance of trade with the Balkans, the political and commercial center of Wallachia began gravitating towards the south; before the end of the 17th century, Bucharest became Wallachia's most populous city, and one of the largest ones in the region, while its landscape became cosmopolitan.[23] This was, however, accompanied by a drastic decrease in princely authority, and a decline of state resources.

On November 13, 1594, the city witnessed widespread violence, upon the start of Michael the Brave's uprising against the Ottomans, and the massacre of Ottoman creditors, who held control over Wallachia's resources, followed by a clash between Wallachians and the Ottoman troops stationed in Bucharest.[24] In retaliation, Bucharest was attacked and almost completely destroyed by Sinan Pasha's forces.[25] It was slowly rebuilt over the following two decades, and again surfaced as a successful competitor to Târgoviște under Radu Mihnea in the early 1620s.[26] Matei Basarab, who divided his rule between Târgoviște and Bucharest, restored the decaying court buildings (1640).[27]

Bucharest was again ravaged, after only 15 years, by the 1655 rebellion of seimeni mercenaries against the rule of Constantin Șerban – the rebel troops arrested and executed a number of high-ranking boyars, before being crushed by Transylvanian troops in June 1655.[28] Constantin Șerban added important buildings to the landscape, but he was also responsible for a destructive fire which was meant to prevent Mihnea III and his Ottoman allies from taking hold of an intact citadel.[29] According to the traveler Evliya Çelebi, the city was rebuilt as rapidly as it was destroyed: "houses of stone or brick [...] are few and unfortunate, given that their gavur masters rebel once every seven-eight years, and the Turks and [their allies] the Tatars consequently set fire to the city; but the inhabitants, in the space of the same year, restore their small one-storeyed, but sturdy, houses".[30] Bucharest was touched by famine and the bubonic plague in the early 1660s (the plague returned in 1675).[31]

Late 1600s

Between Gheorghe Ghica's rule (1659–1660) and the end of Ștefan Cantacuzino's (1715/1716), Bucharest saw a period of relative peace and prosperity (despite the prolonged rivalry between the Cantacuzino and the Băleni families, followed by worsened relations between the former and the Craiovești).[32]

The climactic moment was reached under Șerban Cantacuzino and Constantin Brâncoveanu, when the city embraced the Renaissance under the original form known as the Brâncovenesc style and was expanded (growing to include the area of Cotroceni), furnished with inns maintained by princes, and given its first educational facilities (the princely Saint Sava College, 1694). Brâncoveanu developed Curtea Veche (which probably accommodated the boyar council in its new version), and added two other palaces, including the Mogoșoaia Palace, built in Venetian style and noted for its loggia; this was also the time when the future Calea Victoriei was carved out through Codrii Vlăsiei.[33]

Phanariote era

Early Phanariotes

In 1716, following the anti-Ottoman rebellion of Ștefan Cantacuzino in the context of the Great Turkish War, Wallachia was placed under the more compliant rules of Phanariotes, inaugurated by Nicholas Mavrocordatos (who had previously reigned over Moldavia). These decisively marked Bucharest's development in several ways – the city was the unrivalled capital, being favoured by the decrease in importance of manorialism and rural centers, cumulated with the progress witnessed by the monetary economy (during the period, boyar status began revolving around appointment to administrative offices, and most of the latter were centered on the princely residence, including, after 1761, the banat of Oltenia).[34]

Prince Nicholas' rule coincided with a series of calamities – a major fire, the first Habsburg occupation (in 1716) during the Austro-Turkish War of 1716–1718, and another plague epidemic – but witnessed major cultural achievements inspired by The Enlightenment, such as the creation of a short-lived princely library (maintained by Stephan Bergler).[35] Grigore II Ghica and Constantine Mavrocordatos maintained the commercial infrastructure, and the city became the site of a large market (probably in the Lipscani area) and customs.[36] In 1737, during the Austro-Turkish War of 1737–39, the city was again attacked by Habsburg troops and ransacked by the Nogais, before suffering another major plague outbreak (followed by new outbursts in the 1750s), accompanied by a relative economic decline brought about by the competition between Greek, Levantine and locals for official appointments.[37]

Russo-Turkish Wars

Bucharest was twice occupied by Imperial Russian troops during the War of 1768–74 (initially aided by Pârvu Cantacuzino's anti-Ottoman boyar rebellion, and then stormed by the troops of Nicholas Repnin); the subsequent Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca was partly negotiated in the city.[38]

Under Alexander Ypsilantis, large-scale works to provide the city with fresh water were carried out, and Curtea Veche, destroyed by the previous conflicts, was replaced by a new residence in Dealul Spirii (Curtea Nouă, 1776); his legacy was carried out by Nicholas Mavrogenes.[39] The Russo-Turkish–Austrian War erupted in 1787, and Mavrogenes retreated in front of a new Habsburg invasion, led by Prince Josias of Coburg (1789).[40] Despite other epidemics, coupled with the immense taxes imposed by Constantine Hangerli, and the major earthquake of October 14, 1802 (followed by ones in 1804 and 1812), the city's population continued to increase.[41] During the Russo-Turkish War of 1806–12, Russian troops under Mikhail Andreyevich Miloradovich entered the city to reinstate Constantine Ypsilantis in late December 1806;[42] it was under the latter's rule that Manuc's Inn had been built by Emanuel Mârzaian.

After the peace signed in Bucharest, the rule of John Caradja brought a series of important cultural and social events (the reformist Caragea law, the first hot air balloon ride in the country, the first theater play, the first cloth manufacture, and the first private printing press, Gheorghe Lazăr's educational activities), but also witnessed the devastating Caragea's plague in 1813–1814 – which made between 25,000 and 40,000 casualties.[43] Sources of the time indicate that the city alternated dense agglomerations with large privately owned gardens and orchards, a pattern which made impossible the task of calculating its actual area.[44]

The Greek War of Independence and the contemporary Wallachian uprising brought Bucharest under the brief rule of the pandur leader Tudor Vladimirescu (March 21, 1821), and was then occupied by the Filiki Eteria forces of Major General Alexander Ypsilantis – before seeing the violent Ottoman reprisals (ending in a massacre during August, one which made over 800 victims).[45]

Kiselyov and Alexandru II Ghica

The following non-Phanariote reign of Grigore IV Ghica, acclaimed by the Bucharesters upon its establishment, saw the building of a Neoclassical princely residence in Colentina, the expulsion of foreign clergymen who had competed with Wallachians for religious offices, and the restoration of bridges over the Dâmbovița River, but also high taxes and a number of fires.[46]

Ghica was removed from his position by the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 and the Russian occupation of May 16, 1828; subsequently, the peace of Adrianople placed the whole of the Danubian Principalities' territory under military governorate (still under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire), pending the payment of war reparations by the Ottomans.[47]

After the short governorship of Pyotr Zheltukhin came the prolonged and profoundly influential term of Pavel Kiselyov (November 24, 1829 – 1843), under whom the two Principalities were given their first document resembling a constitution, the Regulamentul Organic (negotiated in Wallachia's capital). Residing in Bucharest, Kiselyov took particular care of the city: he acted against the plague and cholera epidemics of 1829 and 1831, instituted a "city beautifying commission" comprising physicians and architects, paved many central streets with cobblestone (instead of wooden planks), drained the swamps formed around the Dâmboviţa and built public fountains, settled the previously fluctuating borders of the city (it now measured ca.19 km in perimeter and was guarded by patrols and barriers), carved out Calea Dorobanților and Șoseaua Kiseleff (major north–south routes), mapped the city and counted its population, gave Bucharest a garrison for the newly created Wallachian Army and improved its fire fighting service;[48] the changing city was described as unusually cosmopolitan and home to extreme contrasts by French visitor Marc Girardin.[49]

The granting of commercial rights to the Principalities and the retaking of Brăila by Wallachia ensured an economic rebirth under the rule of Prince Alexandru II Ghica,[50] who expanded the number of paved streets and added the new Princely Palace (later replaced by the much larger Royal Palace).[51]

This was also the time the first opposition to Russian rule made itself felt, as the standoff in the Bucharest Assembly between Prince Ghica and the radical Ion Câmpineanu.[52] The city was affected by a minor earthquake in January 1838, and a major flood in March 1839.[53]

1840s and 1850s

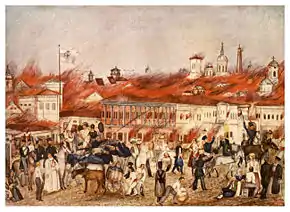

The new prince Gheorghe Bibescu completed a water supply network and works on public gardens, began constructing the National Theater of Romania building (1846; finished in 1852) and improved the chaussées linking Bucharest with other Wallachian centers.[54] On March 23, 1847, the Great Fire of Bucharest consumed around 2,000 buildings (about a third of the city).[55]

Pressured by the revolutionary liberals who had issued the Islaz Proclamation attacking the conservative and increasingly abusive system of the Organic Statute, attacked in the street by a group of young men, and faced with the opposition of the Army, Prince Bibescu accepted cohabitation with a Provisional Government taking inspiration from the European Revolutions on June 12, 1848, and, just a day later, renounced the throne.[56] The new executive, backed by popular shows of support on Filaret field which reunited the Bucharest middle class with peasants from the surrounding area (June 27, August 25), passed a series of radical reformist laws that drew the animosity of Tsar Nicholas I, who pressured the Porte to crush the Wallachian movement; the proposed land reform also led a group of boyars, headed by Ioan Solomon, to attack and arrest the government on July 1 – the effects of this gesture were cancelled on the same day by the inhabitants' reaction and the Ana Ipătescu-led attack on the building occupied by conspirators.[57]

Sultan Abdülmecid I, sympathetic to the anti-Russian scope of the revolt, pressured the revolutionaries to accept a relatively minor change in the executive structure – the Provisional Government ceded position to a more moderate regency (Locotenența Domnească), which was, nevertheless, not recognized by Russia.[58]

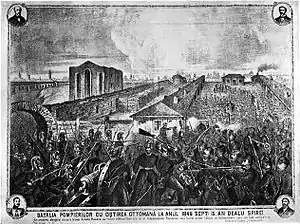

The potential threat of a war between the two powers led Abdülmecid to revise his position and send Fuat Pasha as his observer in Bucharest; at the same time, the city witnessed panic over the threat of a Russian invasion, and the briefly successful coup d'état carried out by Metropolitan Neofit II against the Revolution.[59] On September 18, revolutionary crowds swept into the Interior Ministry, destroyed the lists of assigned boyar ranks and privileges, and forced Neofit to cast an anathema over the Organic Statute: such measures made Fuat Pasha lead Ottoman troops into Bucharest, a move which only met resistance from a group of firemen stationed on Dealul Spirii (who engaged in a shootout after an incident which they perceived as provocation).[60]

Bucharest remained under foreign occupation until late April 1851, and was again held by the Russian troops of Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov during the Crimean War (between July 15, 1853 and July 31, 1854), being ceded to an interim Austrian administration which lasted until the 1856 Treaty of Paris.[61] The three successive foreign administrations brought several improvements to the city (the Bellu cemetery and the Cișmigiu gardens, the telegraph and oil lamp lighting, the creation of new schools and academies, the Știrbei Palace of Prince Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei, and the comprehensive city map drawn by Rudolf Artur Borroczyn).[62]

Capital of the United Principalities

The Paris treaty called for the creation of ad hoc Divans in Moldavia and Wallachia, the first venue for the advocacy of a union between the two countries. Bucharest returned only delegates from the unionist Partida Naţionala to the new forums, but the overall majority in Wallachia was constituted of anti-unionists conservatives; on January 22, 1859, Partida Națională members decided to vote for the Moldavian candidate for Prince, colonel Alexandru Ioan Cuza, who had already been elected in Iași – their vote was carried on January 24, after street pressure forced the other delegates to change their vote, leading to the eventual creation of the United Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, a state with Bucharest as its capital and seat of its Parliament.[63] Cuza, who ruled as Domnitor, paved the Bucharest streets with a better class of cobblestone, established gymnasia and several academic societies (including the University of Bucharest), and ordered the building of a railway between the capital and the Danube port of Giurgiu together with several metallurgical plants in the Ilfov County area; during his day, brick and stone lodgings became the norm.[64]

On February 22, 1866, the city witnessed the coup against Domnitor Cuza, carried out by a coalition of Liberals and Conservatives disenchanted with the attempted land reform and the increasingly authoritarian regime – they occupied the ruler's residence and arrested Cuza and his mistress Marija Obrenović, instating a Regency.[65]

The largely Francophile population of Bucharest came close to causing the fall of Carol I, Cuza's successor, during the Franco-Prussian War, after a clash with the German residents of Bucharest in March 1871 – it was averted by the nomination of the Conservative Lascăr Catargiu as Prime Minister. The welcoming of Russian intervention by Bucharesters at the start of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 contributed to the Ottoman decision to bombard the left bank of the Danube, as Romania's independence was being proclaimed by Parliament.[66]

Capital of the Romanian Kingdom

Belle Époque (1877–1916)

Kiosk in the Cișmigiu Park. Between years 1880s and 1900s, the societies of women and not only had the habit of erecting kiosks in the Cișmigiu Park, where raffles and exhibitions were organised

Kiosk in the Cișmigiu Park. Between years 1880s and 1900s, the societies of women and not only had the habit of erecting kiosks in the Cișmigiu Park, where raffles and exhibitions were organised The Romanian Athenaeum on Victory Avenue by Paul Louis Albert Galeron (1886-1888)

The Romanian Athenaeum on Victory Avenue by Paul Louis Albert Galeron (1886-1888) The Filipescu-Cesianu House on Victory Avenue, now the Museum of Ages (late 19th century)

The Filipescu-Cesianu House on Victory Avenue, now the Museum of Ages (late 19th century).jpg.webp) Middle-class family house with garden and two windows facing the street on Strada Mitropolit Nifon (1897)

Middle-class family house with garden and two windows facing the street on Strada Mitropolit Nifon (1897).jpg.webp) Bourgeois house with garden on Strada General Constantin Budișteanu (1897)

Bourgeois house with garden on Strada General Constantin Budișteanu (1897) The CEC Palace on Victory Avenue by Paul Gottereau (1897-1900)

The CEC Palace on Victory Avenue by Paul Gottereau (1897-1900) Postal card of the Lipscani Street around 1900, with the National Bank of Romania on the right side

Postal card of the Lipscani Street around 1900, with the National Bank of Romania on the right side_in_Bucharest.jpg.webp) Early 20th century interior of the house of painter Eugen Voinescu (1844-1909) in Bucharest

Early 20th century interior of the house of painter Eugen Voinescu (1844-1909) in Bucharest

During the early years of Carol's rule,[67] Bucharest was equipped with gas lighting, the Filaret Station (1869) and Gara de Nord (1872), a horsecar tram system, a telephone system, several factories, boulevards, administrative buildings, as well as large private lodgings (including the Crețulescu Palace). The National Bank of Romania was opened in April 1880, as the first and most important in a series of new banking institutions

Beginning in 1871 the Academy Boulevard was integrated into a large east to west axis which included north-south Victory Road. The construction of this cross-axis in the last three decades of the nineteenth century and was a major task undertaken by Mayor Emanuel Protopopescu. His successor Filipescu continued in the construction of boulevards, one connected the new summer palace built by Carol I to the east–west axis. The second is Lascăr Catargiu Boulevard.

After the proclamation of the Kingdom of Romania in 1881, building works in the city accelerated. In 1883, floodings of the Dâmbovița such as the 1865 flooding of Bucharest, endemic under Cuza, were stopped through the channelling of the river (the change in course modified the neighbourhoods adjacent to the banks).[68] New buildings were added, including the Romanian Athenaeum, and the skyline increased in height – the Athénée Palace, the first one in the city to use reinforced concrete,[69] had five stories. In 1885–1887, after Romania denounced its economic ties with Austria-Hungary, Bucharest's commercial and industrial development went unhindered: over 760 new enterprises were established in the city before 1912, and hundreds more by the 1940s.[70] Limited use of electricity was introduced in 1882.

At the climax of the World War I Romanian Campaign on December 6, 1916, Bucharest was placed under the military occupation of the Central Powers (while the government retreated to Iași). Of the 215 million lei demanded by the new administration in order to cover its expenses, 86 were owed by the capital.[71] After the Compiègne Armistice, German troops evacuated Bucharest, and a Romanian administration was reinstated in late November 1918. As the country was embarking on the course that led to the creation of a Greater Romania (confirmed by the treaties of Saint-Germain, Neuilly and Trianon), its capital witnessed a relatively expanded social crisis – on December 26, 1918, troops fired on compositors engaged in a strike, who had been agitated by the newly created Socialist Party of Romania.[72]

Inter-war

The Victory Avenue in 1923, on a sunday noon

The Victory Avenue in 1923, on a sunday noon_2.jpg.webp) The Marmorosch Blank Bank Palace on Strada Doamnei by Petre Antonescu (1923)

The Marmorosch Blank Bank Palace on Strada Doamnei by Petre Antonescu (1923) The Unification Square in 1926, with the Unification Hall (destroyed in 1986 by the systematization), the Bălașa Lady Church and the Palace of Justice (both still there)

The Unification Square in 1926, with the Unification Hall (destroyed in 1986 by the systematization), the Bălașa Lady Church and the Palace of Justice (both still there).jpg.webp) The Low Priced Dwellings Society Building in the C.A. Rosetti Square by Virginia Andreescu Haret (1926)

The Low Priced Dwellings Society Building in the C.A. Rosetti Square by Virginia Andreescu Haret (1926).jpg.webp) The ASIROM Building on Bulevardul Carol I (1930s)

The ASIROM Building on Bulevardul Carol I (1930s).jpg.webp) The Lido Hotel on Bulevardul Gheorghe Magheru by Ernest Doneaud (1930)

The Lido Hotel on Bulevardul Gheorghe Magheru by Ernest Doneaud (1930) Bulevardul Regina Elisabeta in 1932

Bulevardul Regina Elisabeta in 1932 The Palace of the Society of Civil Servants on Strada Batiștei by Radu Culcer and Ion C. Roșu (1934)

The Palace of the Society of Civil Servants on Strada Batiștei by Radu Culcer and Ion C. Roșu (1934).jpg.webp) The Royal Palace of Bucharest in the Revolution Square on Victory Avenue by Paul Gottereau and Nicolae Nenciulescu (1937)

The Royal Palace of Bucharest in the Revolution Square on Victory Avenue by Paul Gottereau and Nicolae Nenciulescu (1937).jpg.webp) The Foreign Trade Bank on Victory Avenue by Radu Dudescu (1937-1938)

The Foreign Trade Bank on Victory Avenue by Radu Dudescu (1937-1938)%253B_B-II-m-A-19877.JPG.webp) The Victoria Palace in Victory Square by Duiliu Marcu (1940)

The Victoria Palace in Victory Square by Duiliu Marcu (1940)

The elaborate architecture and the city's status as cosmopolitan cultural center won Bucharest the nickname of "Paris of the East" (or Micul Paris – "Little Paris"). Development continued during the 1930s – one of the most prosperous times in Romanian history: after 1928, the population increased by 30,000 inhabitants per year, the area reached 78 km2 in 1939, and many new peripheral boroughs were added (Apărătorii Patriei, Băneasa, Dămăroaia, Floreasca, Giulești, the Militari village, and the first streets in the Balta Albă area).[73] In 1929, the old tram system was replaced by a trolley-based one.[74]

A workers' riot erupted during the Grivița Strike of 1933, ending in a violent clampdown.

Under King Carol II, the city skyline began changing, and numerous art deco- and Neo-Romanian-style buildings and monuments were added, including the new Royal Palace, the Military Academy, Arcul de Triumf, the University of Bucharest Faculty of Law, the new main wing of Gara de Nord, the ANEF Stadium, the Victoria Palace, Palatul Telefoanelor, Dimitrie Gusti's Village Museum, and the present-day Museum of the Romanian Peasant;[75] deep pits were dug to provide Bucharest with safer water, alongside the deviation of the southern course of the Argeș River and the sanitation of the northern lakes (Colentina, Floreasca, Herăstrău, Tei), eventually leading to the creation of the present-day "necklace" of embanked ponds and surrounding parks.[76]

1940s

Bucharest witnessed the birth of three consecutive fascist regimes: after the one established by Carol II and his National Renaissance Front, the outbreak of World War II brought the National Legionary State and, after the bloody Iron Guard Rebellion of January 21–23 (which was accompanied by a major pogrom in the capital), the Ion Antonescu government. In the spring of 1944, it was the target of heavy RAF and USAF bombings (see Bombing of Bucharest in World War II). The city was also the center of King Michael I's August 23 coup, which took the country out of the Axis and into the ranks of the Allies; consequently, it became the target of German reprisals – on August 23–24, a large-scale bombing by the Luftwaffe destroyed the National Theater and damaged other buildings, while the Wehrmacht engaged in street-fighting with the Romanian Army.[77] On August 31, the Soviet Red Army entered Bucharest.

In February 1945, the Romanian Communist Party organized a protest in front of the Royal Palace, which witnessed violence and ended in the fall of the Nicolae Rădescu cabinet and the coming to power of the Communist-backed Petru Groza. On November 8, the King's Day, the new administration suppressed pro-Monarchy rallies – the onset of political repression throughout the country.

Communist era

The House of the Free Press by Horia Maicu and Nicolae Bădescu (1952-1957)

The House of the Free Press by Horia Maicu and Nicolae Bădescu (1952-1957).JPG.webp) Sala Palatului by Horia Maicu, Tiberiu Ricci, Ignace Șerban and Romeo Ștefan Belea (1959-1960)

Sala Palatului by Horia Maicu, Tiberiu Ricci, Ignace Șerban and Romeo Ștefan Belea (1959-1960)_-_panoramio.jpg.webp) Socialist-era apartment blocks on Bulevardul Constantin Brancoveanu

Socialist-era apartment blocks on Bulevardul Constantin Brancoveanu.jpg.webp) Socialist-era apartment blocks on Bulevardul Iuliu Maniu

Socialist-era apartment blocks on Bulevardul Iuliu Maniu Apartment blocks on Unirii Boulevard (1980s)

Apartment blocks on Unirii Boulevard (1980s) Destruction of Belle Époque and interwar city-houses in 1987 during the systematization, in order to be replaced with prefabricated apartment blocks

Destruction of Belle Époque and interwar city-houses in 1987 during the systematization, in order to be replaced with prefabricated apartment blocks The Obor Square in 1987, when most food was exported and what remained was given to the population

The Obor Square in 1987, when most food was exported and what remained was given to the population The Obor metro station (late 1980s)

The Obor metro station (late 1980s)

The Communist regime was firmly established after the proclamation of a People's Republic on December 30, 1947. One of the major landscape interventions by early Communist leaders was the addition of Socialist realist buildings, including the large Casa Scînteii (1956) and the National Opera. As a tendency for the entire period of Communist rule, the city underwent massive geographical and populational expansion: it began extending, westwards, eastwards and southwards, with new, tower block-dominated districts such as Titan, Militari, Pantelimon, Dristor, and Drumul Taberei.

During Nicolae Ceaușescu's leadership, a part of the historical part of the city, including old churches, was destroyed, to be replaced with the immense buildings of Centrul Civic – notably, the Palace of the Parliament, which replaced about 1.8 square kilometres (0.69 sq mi) of old buildings (see Ceaușima). Alongside buildings characterised by a continuation of Socialist realism, Bucharest was home to several large-scale ones of a more generic modernist style (Sala Palatului, the Globus Circus, and the Intercontinental Hotel).[78] By the time it was toppled, the regime had begun constructing a series of huge identical markets, commonly known as "hunger circuses", and started digging the never-finished Danube–Bucharest Canal. The Dâmbovița River was channeled for a second time, and the Bucharest Metro, noted for its compliance with official aesthetics, was opened in 1979.

In 1977, the 7.2 Mw Vrancea earthquake claimed 1,500 lives and destroyed many old lodgings and offices. On August 21, 1968, Ceaușescu's Bucharest speech condemning the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia led many inhabitants to briefly join the paramilitary Patriotic Guards – created on the spot as defense against a possible Soviet military reaction to Romania's new stance.

1989 to present-day

.jpg.webp) Apartment blocks on Strada Glădiței near the Văcărești Nature Park (late 2000s-early 2010s)

Apartment blocks on Strada Glădiței near the Văcărești Nature Park (late 2000s-early 2010s) Interior of Cărturești Carusel, a former bank built in the 1900s on Strada Lipscani, renovated and transformed into a bookshop in 2015

Interior of Cărturești Carusel, a former bank built in the 1900s on Strada Lipscani, renovated and transformed into a bookshop in 2015.jpg.webp) Mega Mall on Bulevardul Pierre de Coubertin (2015)

Mega Mall on Bulevardul Pierre de Coubertin (2015).jpg.webp) Minimalist house no. 4A on Strada Dimitrie Racoviță (probably late 2010s)

Minimalist house no. 4A on Strada Dimitrie Racoviță (probably late 2010s) The Romanian Athenaeum illuminated on April 13, 2018, during a Festival of Lights

The Romanian Athenaeum illuminated on April 13, 2018, during a Festival of Lights

During the Romanian Revolution of 1989, which began in Timișoara, Bucharest was the site of a rapid succession of major events between December 20 and December 22, leading to the overthrow of Ceaușescu's communist regime. Unhappy with some results of the revolution, students' leagues and other organizations, including the Civic Alliance, organized mass protests against the National Salvation Front government in 1990 (in what became known as Golaniad); these were violently suppressed by the miners of Valea Jiului – the Mineriad of June 14–15. Several other Mineriads followed – only one of them (the September 1991 Mineriad) succeeded in reaching Bucharest, being responsible for the fall of the Petre Roman government.

After the year 2000, due to the advent of Romania's economic boom, the city has modernized and several historical areas have been restored. In 1992, the first connection to the Internet took place at the Polytechnic University of Bucharest.

The Colectiv nightclub fire killed 64 individuals, in a fast-spreading fire and resulting stampede, in October 2015. It was the country's deadliest-ever nightclub fire, the city's (and one of Romania's) worst accidental losses of life since the end of the civil war in 1989, and one of the deadliest incidents of any kind since that time. Many victims who were not trampled to death were killed through smoke inhalation and/or extensive burns. Three days of national mourning were observed, and blood drives were held.

Administrative history

A local administration was first attested under Petru cel Tânăr (in 1563), when a group of pârgari countersigned a property purchase; the city's borders, established by Mircea Ciobanul, were confirmed by Matei Basarab in the 1640s, but the inner borders between properties remained rather chaotic, and were usually confirmed periodically by the Jude and his pârgari.[79] Self-administration privileges were denied to Bucharesters and taken over by the Princes during the rule of Constantin Brâncoveanu and the Regulamentul Organic period – in 1831, the population was allowed to elect a local council and was awarded a local budget; the council was expanded under Alexandru Ioan Cuza, under whom the first Mayor of Bucharest, Barbu Vlădoianu, was elected.[80]

The guilds (bresle or isnafuri), covering a large range of employments and defined either by trade or ethnicity, formed self-administrating units from the 17th century until the late 19th century. Several isnafuri in the Lipscani area gave their names to streets which still exist. Although they lacked clear defense duties, given that Bucharest was not fortified, they became the basis for military recruitment in the small city garrison. Trading guilds became predominant over those of artisans during the 19th century, and all autochthonous ones collapsed under competition from the sudiți wholesale traders (protected by foreign diplomats), and disappeared altogether after 1875, when mass-produced imports from Austria-Hungary flooded the market.[81]

Religious and communal history

_-_IMG_02.jpg.webp)

Bucharest is home to the Romanian Orthodox Patriarchy and the Wallachian Metropolitan seat, of the Roman Catholic Archbishopric (established in 1883) and Apostolic Nunciature, of the Archbishopric and Eparchy Council of the local Armenian Apostolic Church, of the leadership of the Federation of the Jewish Communities of Romania as well as an important site for other religions and churches.

In Nicolae Ceaușescu's times, a large number of religious locations were demolished to make room for tower blocks and other landmarks; the former included Văcărești Monastery, which was torn down during works to enlarge the Văcărești Lake.

Romanian Orthodoxy

For much of Bucharest's history, its neighbourhoods were designated by the names of the more important Orthodox churches in the respective areas. The first major religious monument in the city was the Curtea Veche church, built by Mircea Ciobanul in the 1550s, followed by Plumbuita (consecrated by Peter the Younger).

Constantin Șerban erected the Metropolitan Church (today's Patriarchal Cathedral) in 1658, moving the bishopric from Târgoviște in 1668.[82] In 1678, under Șerban Cantacuzino, the Bishopric was equipped with a printing press, which published the first Romanian-language edition of the Bible (the Cantacuzino Bible) during the following year.[83]

The large-scale urban development under Prince Șerban and Prince Constantin Brâncoveanu saw the building of numerous religious facilities, including Anthim the Iberian's Antim Monastery; in 1722, boyar Iordache Crețulescu added Kretzulescu Church to the city's landscape,[84] during a period when most new places of worship were being dedicated by trader guilds.[85]

Phanariote rulers consecrated several major places of worship, including, among others, the Văcărești Monastery (1720), a monumental late-Byzantine site, the Stavropoleos Church (1724) – both built under Nicholas Mavrocordatos -, Popa Nan (1719), Domnița Bălașa (1751), the one in Pantelimon (1752), Schitu Măgureanu (1756), Icoanei (1786), and Amzei (ca.1808).[86] Another period of growth in the building of Orthodox religious sites was the inter-war one: 23 new churches were added before 1944.[87]

Jewish history of Bucharest

The Jewish community of Bucharest was, at least initially, overwhelmingly Sephardi (until Ashkenazim began arriving from Moldavia in the early 19th century). Jews were first attested as shop owners under Mircea Ciobanul (ca.1550), and despite frequent persecutions and pogroms, formed a large part of the professional elites for most of Bucharest's history, and the largest percentage of the total population after Romanians (around 11%). The main Jewish-inhabited areas were centered on the present-day Unirii Square, Dudești and Văcărești neighbourhoods.[88]

In World War II, Jews were the target of widespread violence during the National Legionary State regime and, many were attacked and had their property looted, while others were eventually killed. During the Iron Guard Rebellion in January 1941 some 130 Jews were brutally tortured and murdered. A certain number of local Jews were deported to Transnistria by the Ion Antonescu regime, but most of them remained on the spot, being forcefully assigned to labor duties like cleaning out snow, sorting out the debris resulting from Allied bombings etc.[89] As a result of the WWII holocaust and emigration both to Israel and other countries the Jewish population was drastically reduced. Notable institutions of the community nowadays include the Bucharest Synagogue and the State Jewish Theater.

Other communities

Majority-Eastern Orthodox groups other than Romanians included sizeable communities of Greeks (a highly influential and omnipresent one for much of the city's history, it was mentioned in Bucharest as early as 1561 and, after reaching its peak in the 18th century, entered a process of regression), Aromanians (first attested in 1623, but probably counted among the Greeks by previous testimonials), Serbs and Bulgarians, alongside other South Slavs (Bulgarians and Serbs were confounded in common reference until the 19th century; at the same time, sources more readily distinguished between groups of traders from Gabrovo, Chiprovtsi, or Razgrad; an important group of Bulgarians retreated with the Russians at the close of the war of 1828–1829, and settled in Bucharest as gardeners and milkmen), as well as Arab parishioners of the Antiochian Orthodox Church, Russians (see also Bucharest Russian Church), and most of the Albanians present.[90] Protected by the Church more than actually being considered its parishioners,[91] the Roma were, until 1855, slaves of boyars and of the Church itself; in 1860, 9,000 Bucharesters were thought to have been Roma.[92]

Presently, there are 18 Roman Catholic places of worship in Bucharest, including Bărăţia (built in 1741, rebuilt 1861), the Saint Joseph Cathedral (1884) and the Italian Church (1916). The Romanian Catholic community (which includes adherents to the Eastern Rite Church) has traditionally been accompanied by the presence of majority-Catholic ethnic groups: Ragusan traders were first mentioned in the 16th century; Italians, recorded ca.1630, were traditionally employed as stonemasons; a Polish minority became notable after the 1863 January Uprising forced many to take refuge in Romania; the French, highly influential during the late 18th century and early 19th century, grouped 700 ethnics by the 1890s; between the two World Wars, Bucharest became home to a large Székely community (probably some tens of thousands).[93]

Mostly Gregorian Armenians, who originally came from Kamianets-Podilskyi and Rousse, were first mentioned in the 17th century, and left their mark on the entire city with the activities of Manuc-bei and Krikor Zambaccian (see also: Armenians in Romania). They built their first church ca.1638, and their first Armenian-language school in 1817; a new church, built on the model of the one in Echmiadzin, was consecrated in 1911.[94]

Most Protestants in Bucharest have traditionally been Calvinist Magyars and German Lutherans, who accounted for several thousands of the city's inhabitants;[95] mentioned as early as 1574, Lutherans have a church just north of Sala Palatului, on Strada Luterană (the Lutheran Street).

Islam was initially present through the means of the relatively minor Turkish community and small groups of Muslim Romas and Muslim Arabs;[96] it is now represented by a growing, largely Middle Eastern immigrant community. In 1923, a mosque was constructed in Carol Park.

Population history

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1595 | 10,000 |

| 1650 | 20,000 |

| 1789 | 30,030 property-owners; 6,000 houses |

| 1810 | 42,000 (of which 32,185 Orthodox Christians)[97] |

| 1831 | 60,587 (property-owners; 10,000 houses) |

| 1859 | 121,734 |

| 1877 | 177,646 |

| 1900 | 282,000 |

| 1912 | 341,321 |

| 1918 | 383,000 |

| 1930 | 639,040 |

| 1941 | 992,000 |

| 1948 | 1,025,180 |

| 1956 | 1,177,661 |

| 1966 | 1,366,684 |

| 1977 | 1,807,239 |

| 1992 | 2,064,474 |

| 2000 | 2,300,000 |

| 2002 | 1,926,334 |

| 2003 | 2,082,000 |

| 2011 | 1,883,425 |

| 2016 | 2,106,144 |

Treaties signed in Bucharest

| Treaty of May 28, 1812, at the end of the Russo-Turkish War |

| Treaty of March 3, 1886, at the end of the Serbo-Bulgarian War |

| Treaty of August 10, 1913, at the end of the Second Balkan War |

| Treaty of August 4, 1916, the treaty of alliance between Romania and the Entente |

| Treaty of May 6, 1918, the treaty between Romania and the Central Powers |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Țînțăreanu, Alex. (1959). BUCUREȘTI Scurt Istoric (in Romanian). S.P.C. Muzeul de Istorie a Orașului București. p. 7, 8.

- ↑ Giurescu, p.25-26; Morintz and Rosetti, p.12-18

- ↑ Giurescu, p.26; Morintz and Rosetti, p.18-27

- ↑ For the dispute's relevancy to Bucharest, see Giurescu, p.30

- ↑ Giurescu, p.32-34; Morintz and Rosetti, p.28-31

- ↑ Giurescu, p.33; Morintz and Rosetti, p.28-29

- ↑ Giurescu, p.37; Morintz and Rosetti, p.33

- ↑ Giurescu, p.38

- ↑ Giurescu, p.38-39

- ↑ Giurescu, p.39; Morintz and Rosetti, p.33

- ↑ Giurescu, p.39

- ↑ Giurescu, p.39; Morintz and Rosetti, p.34

- ↑ Giurescu, p.42; Ionașcu and Zirra, p.56

- ↑ Giurescu, p.44

- ↑ Giurescu, p.42, 47; Ionaşcu and Zirra, p.58

- ↑ Ionașcu and Zirra, p.58-59, 75

- ↑ Giurescu, p.50; Ionaşcu and Zirra, p.58

- ↑ Giurescu, p.52

- ↑ Giurescu, p.53

- ↑ Giurescu, p.53-55, 61; p.147, 154–155

- ↑ Giurescu, p.57

- ↑ Giurescu, p.60-61, 63

- ↑ Giurescu, p.59, 77

- ↑ Giurescu, p.63-64

- ↑ Giurescu, p.64-67; Ionașcu and Zirra, p.65-67

- ↑ Giurescu, p.68-71

- ↑ Giurescu, p.71; Ionaşcu and Zirra, p.69; Rosetti, p.163

- ↑ Giurescu, p.73

- ↑ Giurescu, p.74

- ↑ Çelebi, in Giurescu, p.75

- ↑ Giurescu, p.74-75, 79

- ↑ Cantea, p.99-100; Giurescu, p.77-79

- ↑ Djuvara, p.212; Giurescu, p.79-86

- ↑ Giurescu, p.93-94

- ↑ Djuvara, p.47-48, 92; Giurescu, p.94-96

- ↑ Giurescu, p.96

- ↑ Giurescu, p.96-98

- ↑ Djuvara, p.49, 285; Giurescu, p.98-99

- ↑ Djuvara, p.49, 207; Giurescu, p.103-105

- ↑ Giurescu, p.105-106

- ↑ Djuvara, p.281-282; Giurescu, p.106-108

- ↑ Djuvara, p.287-288; Giurescu, p.107-109

- ↑ Djuvara, p.215, 287–288, 293–295; Giurescu, p.110-111, 130

- ↑ Djuvara, p.165, 168–169; Giurescu, p.252

- ↑ Djuvara, p.298-304, 293–295; Giurescu, p.114-119

- ↑ Djuvara, p.147; Giurescu, p.119-120

- ↑ Djuvara, p.321; Giurescu, p.122

- ↑ Giurescu, p.122-125

- ↑ Girardin, in Djuvara, p.105-106, 166, in Giurescu, p.126-127

- ↑ Giurescu, p.127

- ↑ Djuvara, p.113; Giurescu, p.127-128

- ↑ Djuvara, p.329; Giurescu, p.134

- ↑ Giurescu, p.130-131

- ↑ Djuvara, 207; Giurescu, p.127-130, 141

- ↑ Giurescu, p.130

- ↑ Djuvara, p.324, 330–331; Giurescu, p.133

- ↑ Giurescu, p.135

- ↑ Giurescu, p.135-136

- ↑ Giurescu, p.136

- ↑ Giurescu, p.137

- ↑ Giurescu, p.139-140

- ↑ Giurescu, p.140-142, 260

- ↑ Giurescu, p.142

- ↑ Giurescu, p.144, 150, 152

- ↑ Giurescu, p.149

- ↑ Giurescu, p.152-153

- ↑ Giurescu, p.154-161, 169–171

- ↑ Giurescu, p.157, 161, 163

- ↑ Giurescu, p.166

- ↑ Giurescu, p.167, 181–185

- ↑ Giurescu, p.176

- ↑ Giurescu, p.177-178

- ↑ Giurescu, p.189-191

- ↑ Giurescu, p.196, 198

- ↑ Giurescu, p.191-195

- ↑ Patrimoniul Arhitectural al Secolului XX (Arhitectura Art-Deco, Căutările naționale – arhitectura neoromânească); Giurescu, p.198-199

- ↑ Giurescu, p.211-212

- ↑ Patrimoniul Arhitectural al Secolului XX (Arhitectura dictaturii ceauȘiste)

- ↑ Giurescu, p.55, 60, 71, 333–334

- ↑ Giurescu, p.338, 349

- ↑ Djuvara, 184–187; Giurescu, 288–289

- ↑ Giurescu, p.73-74

- ↑ Giurescu, p.77

- ↑ Giurescu, p.86-87; Rosetti, p. 163

- ↑ Giurescu, p.89-90

- ↑ Djuvara, p.47; Ionașcu and Zirra, p.75; Giurescu, p.94, 96, 100–101

- ↑ Giurescu, p.194

- ↑ Djuvara, p.179; Giurescu, p.271-272

- ↑ Giurescu, p.208

- ↑ Djuvara, p.183; Giurescu, p.124, 183, 267–269, 272–273

- ↑ Djuvara, p.270

- ↑ Giurescu, p.267, 274

- ↑ Giurescu, p.62, 269, 272–274

- ↑ Djuvara, p.178; Giurescu, p.270-271

- ↑ Djuvara, 179; Giurescu, p.272

- ↑ Giurescu, p.273

- ↑ Ionescu, p.10

References

- Neagu Djuvara, Între Orient și Occident. Tările române la începutul epocii moderne, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995

- Constantin C. Giurescu, Istoria Bucureștilor. Din cele mai vechi timpuri pînă în zilele noastre, Ed. Pentru Literatură, Bucharest, 1966

- Ștefan Ionescu, Bucureștii în vremea fanarioţilor, Editura Dacia, Cluj, 1974

- Muzeul de Istorie a Orașului București, Bucureștii de odinioară, Editura Științifică, Bucharest, 1959:

- (Cap. I.) Sebastian Morintz, D. V. Rosetti, "Din cele mai vechi timpuri și pînă la formarea Bucureștilor" (pp. 11–35)

- (Cap. II) I. Ionașcu, Vlad Zirra, "Mănăstirea Radu Vodă și biserica Bucur" (pp. 49–77)

- (Cap. III) Gh. Cantea, "Cercetări arheologice pe dealul Mihai Vodă și în împrejurimi" (pp. 93–127)

- (Cap. IV) D. V. Rosetti, "Curtea Veche" (pp. 146–165)

- Uniunea Arhitecților din România, Patrimoniul Arhitectural al Secolului XX – România, Prezentare generală

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)