| History of Estonia |

|---|

|

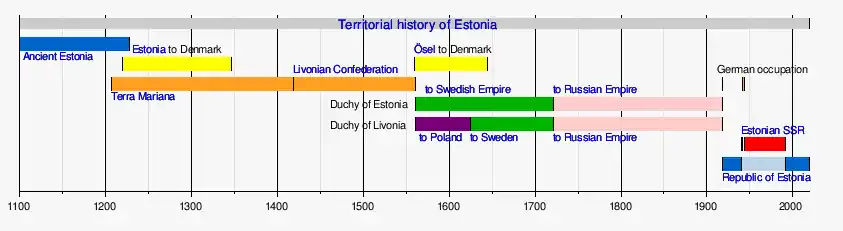

| Chronology |

|

|

The history of Estonia forms a part of the history of Europe. Humans settled in the region of Estonia near the end of the last glacial era, beginning from around 9000 BC.

Ancient Estonia: pre-history

Mesolithic Period

The region has been populated since the end of the Late Pleistocene glaciation, about 9,000 BC. The earliest traces of human settlement in Estonia are connected with the Kunda culture. The early mesolithic Pulli settlement is located by the Pärnu River. It has been dated to the beginning of the 9th millennium BC. The Kunda culture received its name from the Lammasmäe settlement site in northern Estonia, which dates from earlier than 8500 BC.[1] Bone and stone artifacts similar to those found at Kunda have been discovered elsewhere in Estonia, as well as in Latvia, northern Lithuania and southern Finland. Among minerals, flint and quartz were used the most for making cutting tools.

Neolithic Period

The beginning of the Neolithic Period is marked by the ceramics of the Narva culture, and appear in Estonia at the beginning of the 5th millennium. The oldest finds date from around 4900 BC. The first pottery was made of thick clay mixed with pebbles, shells or plants. The Narva-type ceramics are found throughout almost the entire Estonian coastal region and on the islands. The stone and bone tools of the era have a notable similarity with the artifacts of the Kunda culture.

Around the beginning of 4th millennium BC Comb Ceramic culture arrived in Estonia.[2] Until the early 1980s the arrival of Balto-Finnic peoples, the ancestors of the Estonians, Finns, and Livonians, on the shores of the Baltic Sea was associated with the Comb Ceramic Culture.[3] However, such a linking of archaeologically defined cultural entities with linguistic ones cannot be proven, and it has been suggested that the increase of settlement finds in the period is more likely to have been associated with an economic boom related to the warming of climate. Some researchers have even argued that a Uralic form of language may have been spoken in Estonia and Finland since the end of the last glaciation.[4]

The burial customs of the comb pottery people included additions of figures of animals, birds, snakes and men carved from bone and amber. Antiquities from comb pottery culture are found from northern Finland to eastern Prussia.

The beginning of the Late Neolithic Period about 2200 BC is characterized by the appearance of the Corded Ware culture, pottery with corded decoration and well-polished stone axes (s.c. boat-shape axes). Evidence of agriculture is provided by charred grains of wheat on the wall of a corded-ware vessel found in Iru settlement. Osteological analysis show an attempt was made to domesticate the wild boar.[5]

Specific burial customs were characterized by the dead being laid on their sides with their knees pressed against their breast, one hand under the head. Objects placed into the graves were made of the bones of domesticated animals.[2]

Bronze Age

The beginning of the Bronze Age in Estonia is dated to approximately 1800 BC. The development of the borders between the Finnic peoples and the Balts was under way. The first fortified settlements, Asva and Ridala on the island of Saaremaa and Iru in northern Estonia, began to be built. The development of shipbuilding facilitated the spread of bronze. Changes took place in burial customs, a new type of burial ground spread from Germanic to Estonian areas, and stone cist graves and cremation burials became increasingly common, alongside a small number of boat-shaped stone graves.[6]

About the 7th century BC, a large meteorite hit Saaremaa island and created the Kaali craters.

About 325 BC, the Greek explorer Pytheas possibly visited Estonia. The Thule island he described has been identified as Saaremaa by Lennart Meri,[7] though this identification is not widely considered probable, as Saaremaa lies far south of the Arctic Circle.

Iron Age

The Pre-Roman Iron Age began in Estonia about 500 BC and lasted until the middle of the 1st century AD. The oldest iron items were imported, although since the 1st century iron was smelted from local marsh and lake ore. Settlement sites were located mostly in places that offered natural protection. Fortresses were built, although used temporarily. The appearance of square Celtic fields surrounded by enclosures in Estonia date from the Pre-Roman Iron Age. The majority of stones with man-made indents, which presumably were connected with magic designed to increase crop fertility, date from this period. A new type of grave, quadrangular burial mounds, began to develop. Burial traditions show the clear beginning of social stratification. The Roman Iron Age in Estonia is roughly dated to between 50 and 450 AD, the era that was affected by the influence of the Roman Empire. In material culture this is reflected by a few Roman coins, some jewellery and artefacts. The abundance of iron artefacts in southern Estonia speaks of closer mainland ties with southern areas, while the islands of western and northern Estonia communicated with their neighbors mainly by sea. By the end of the period three clearly defined tribal dialectical areas—northern Estonia, southern Estonia, and western Estonia including the islands—had emerged, the population of each having formed its own understanding of identity.[8]

Early Middle Ages

The name "Estonia" occurs first in a form of Aestii in the 1st century AD by Tacitus; however, it might have indicated Baltic tribes living in the area. In the Scandinavian sagas (9th century) the term started to be used to indicate the Estonians.[9]

Ptolemy in his Geography III in the middle of the 2nd century CE mentions the Osilians among other dwellers on the Baltic shore.[10]

According to the 5th-century Roman historian Cassiodorus, the people known to Tacitus as Aestii were the Estonians. The extent of their territory in early medieval times is disputed, but the nature of their religion is not. They were known to the Scandinavians as experts in wind-magic, as were the Lapps (known at the time as Finns) in the North.[11] Cassiodorus mentions Estonia in his book V. Letters 1–2 dating from the 6th century.[12]

The Chudes, as mentioned by a monk Nestor in the earliest Kyivan Rus chronicles, were the Ests or Esthonians.[13]

In the 1st centuries AD political and administrative subdivisions began to emerge in Estonia. Two larger subdivisions appeared: the parish (kihelkond) and the county (maakond). The parish consisted of several villages. Nearly all parishes had at least one fortress. The defense of the local area was directed by the highest official, the parish elder. The county was composed of several parishes, also headed by an elder. By the 13th century the following major counties had developed in Estonia: Saaremaa (Osilia), Läänemaa (Rotalia or Maritima), Harjumaa (Harria), Rävala (Revalia), Virumaa (Vironia), Järvamaa (Jervia), Sakala (Saccala), and Ugandi (Ugaunia).[14]

Varbola Stronghold was one of the largest circular rampart fortresses and trading centers built in Estonia, Harju County (Latin: Harria) at the time.

In the 11th century the Scandinavians are frequently chronicled as combating the Vikings from the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. With the rise of Christianity, centralized authority in Scandinavia and Germany eventually led to the Baltic crusades. The east Baltic world was transformed by military conquest: first the Livs, Letts and Estonians, then the Prussians and the Finns underwent defeat, baptism, military occupation and sometimes extermination by groups of Germans, Danes and Swedes.[15]

Estonian Crusade: The Middle Ages

Estonia was one of the last corners of medieval Europe to be Christianized. In 1193 Pope Celestine III called for a crusade against pagans in Northern Europe. The Northern Crusades from northern Germany established the stronghold of Riga (in modern Latvia). With the help of the newly converted local tribes of Livs and Letts, the crusaders initiated raids into part of what is present-day Estonia in 1208. Estonian tribes fiercely resisted the attacks from Riga and occasionally themselves sacked territories controlled by the crusaders. In 1217 the German crusading order the Sword Brethren and their recently converted allies won a major battle in which the Estonian commander Lembitu was killed.

Danish Estonia (1219–1346)

Northern Estonia was conquered by Danish crusaders led by king Waldemar II, who arrived in 1219 on the site of the Estonian town of Lindanisse[16] (now Tallinn) at (Latin) Revelia (Estonian) Revala or Rävala, the adjacent ancient Estonian county. The Danish Army defeated the Estonians at the Battle of Lindanise.

The Estonians of Harria started a rebellion in 1343 (St. George's Night Uprising). The province was occupied by the Livonian Order as a result. In 1346, the Danish dominions in Estonia (Harria and Vironia) were sold for 10 000 marks to the Livonian Order.

Swedish coastal settlements

The first written mention of the Estonian Swedes comes from 1294, in the laws of the town of Haapsalu. Estonian Swedes are one of the earliest known minorities in Estonia. They have also been called "Coastal Swedes" (Rannarootslased in Estonian), or according to their settlement area Ruhnu Swedes, Hiiu Swedes etc. They themselves used the expression aibofolke ("island people"), and called their homeland Aiboland.

The ancient areas of Swedish settlement in Estonia were Ruhnu Island, Hiiumaa Island, the west coast and smaller islands (Vormsi, Noarootsi, Sutlepa, Riguldi, Osmussaar), the northwest coast of the Harju District (Nõva, Vihterpalu, Kurkse, the Pakri Peninsula and the Pakri Islands), and Naissaar Island near Tallinn. The towns with a significant percentage of Swedish population have been Haapsalu and Tallinn.

In earlier times Swedes also lived on the coasts of Saaremaa, the southern part of Läänemaa, the eastern part of Harjumaa and the western part of Virumaa.

Terra Mariana

In 1227 the Sword Brethren conquered the last indigenous stronghold on the Estonian island of Saaremaa. After the conquest, all the remaining local pagans of Estonia were ostensibly Christianized. An ecclesiastical state Terra Mariana was established. The conquerors exercised control through a network of strategically located castles.[17]

The territory was then divided between the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order, the Bishopric of Dorpat (in Estonian: Tartu piiskopkond) and the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek (in Estonian: Saare-Lääne piiskopkond). The northern part of Estonia – more exactly Harjumaa and Virumaa districts (in German: Harrien und Wierland) – was a nominal possession of Denmark until 1346. Tallinn (Reval) was given the Lübeck Rights in 1248 and became the northernmost member city of the Hanseatic League at the end of the 13th century. In 1343, the people of northern Estonia and Saaremaa (Oesel) Island started a rebellion (St. George's Night Uprising) against the rule of their German-speaking landlords. The uprising was put down, and four elected Estonian "kings" were killed in Paide during peace negotiations in 1343. Vesse, the rebel King of Saaremaa, was hanged in 1344.[18] Despite the rebellions, and Muscovite invasions in 1481 and 1558, the Middle Low German-speaking minority established themselves as the dominating force in the society of Estonia, both as traders and the urban middle-class in the cities, and as landowners in the countryside, through a network of manorial estates.[19]

The Reformation

The Protestant Reformation in Europe that was initiated in 1517 by Martin Luther spread rapidly to Estonia in the 1520s. Lutheranism spread literacy among the commoners. However, many peasants were traditionalists and more comfortable with Catholic traditions; they delayed the adoption of the new church. After 1600, Swedish Lutheranism began to dominate the building, furnishing, and (modest) decoration of new churches. Church architecture was now designed to encourage congregational understanding of and involvement in the services. Pews and seats were installed for the common people to make listening to the sermon less of a burden, and altars often featured depictions of the Last Supper, but images and statues of the saints had disappeared.[20] Church services were now given in the local vernacular, instead of Latin, and the first books were printed in Estonian.[21]

Division of Estonia in the Livonian War

During the Livonian War in 1561, northern Estonia submitted to Swedish control, while southern Estonia briefly came under the control of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 1580s. In 1625, mainland Estonia came entirely under Swedish rule. Estonia was administratively divided between the provinces of Estonia in the north and Livonia in southern Estonia and northern Latvia, a division which persisted until the early 20th century.

Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor asked for help of Gustav I of Sweden, and the Kingdom of Poland also began direct negotiations with Gustavus, but nothing resulted because on 29 September 1560, Gustavus I Vasa died. The chances for success of Magnus von Lyffland and his supporters looked particularly good in 1560 and 1570. In the former case he had been recognised as their sovereign by the Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek and the Bishopric of Courland, and as their prospective ruler by the authorities of the Bishopric of Dorpat; the Bishopric of Reval with the Harrien-Wierland gentry were on his side; and the Livonian Order conditionally recognised his right of ownership of the principality of Estonia. Then, along with Archbishop Wilhelm von Brandenburg of the Archbishopric of Riga and his coadjutor Christoph von Mecklenburg, Kettler gave to Magnus the portions of the Kingdom of Livonia which he had taken possession of, but they refused to give him any more land. Once Eric XIV of Sweden became king, he took quick actions to get involved in the war. He negotiated a continued peace with Muscovy and spoke to the burghers of Reval city. He offered them goods to submit to him, as well as threatening them. By 6 June 1561, they submitted to him, contrary to the persuasions of Kettler to the burghers. The King's brother Johan married the Polish princess Catherine Jagiellon. Wanting to obtain his own land in Livonia, he loaned Poland money and then claimed the castles they had pawned as his own instead of using them to pressure Poland. After Johan returned to Finland, Erik XIV forbade him to deal with any foreign countries without his consent. Shortly after that Erik XIV started acting quickly and lost any allies he was about to obtain, either from Magnus or the Archbishop of Riga. Magnus was upset he had been tricked out of his inheritance of Holstein. After Sweden occupied Reval, Frederick II of Denmark made a treaty with Erik XIV of Sweden in August 1561. The brothers were in great disagreement, and Frederick II negotiated a treaty with Ivan IV on 7 August 1562, in order to help his brother obtain more land and stall further Swedish advance. Erik XIV did not like this and the Northern Seven Years' War between the Free City of Lübeck, Denmark, Poland, and Sweden broke out. While only losing land and trade, Frederick II and Magnus were not faring well. But in 1568, Erik XIV became insane, and his brother Johan III took his place. Johan III ascended to the throne of Sweden, and due to his friendship with Poland he began a policy against Muscovy. He would try to obtain more land in Livonia and exercise strength over Denmark. After all parties had been financially drained, Frederick II let his ally, King Sigismund II Augustus of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, know that he was ready for peace. On 13 December 1570, the Treaty of Stettin was concluded. It is, however, more difficult to estimate the scope and magnitude of the support Magnus received in Livonian cities. Compared to the Harrien-Wierland gentry, the Reval city council, and hence probably the majority of citizens, demonstrated a much more reserved attitude towards Denmark and King Magnus of Livonia. Nevertheless, there is no reason to speak about any strong pro-Swedish sentiments among the residents of Reval. The citizens who had fled to the Bishopric of Dorpat or had been deported to Muscovy hailed Magnus as their saviour until 1571. The analysis indicates that during the Livonian War a pro-independence wing emerged among the Livonian gentry and townspeople, forming the so-called "Peace Party". Dismissing hostilities, these forces perceived an agreement with Muscovy as a chance to escape the atrocities of war and avoid the division of Livonia. That is why Magnus, who represented Denmark and later struck a deal with Ivan the Terrible, proved a suitable figurehead for this faction.

The Peace Party, however, had its own armed forces – scattered bands of household troops (Hofleute) under diverse command, which only united in action in 1565 (Battle of Pärnu and Siege of Reval, 1565), in 1570–1571 (Siege of Reval, 1570–1571; 30 weeks), and in 1574–1576 (first on Sweden's side, then came the sale of Wiek to the Danish Crown and the loss of the territory to the Muscovites). In 1575 after Muscovy attacked Danish claims in Livonia, Frederick II dropped out of the competition, as did the Holy Roman Emperor. After this Johan III held off on his pursuit for more land due to Muscovy obtaining lands that Sweden controlled. He used the next two years of truce to get in a better position. In 1578, he resumed the fight for not only Livonia, but also everywhere due to an understanding he made with Rzeczpospolita. In 1578 Magnus retired to Rzeczpospolita, and his brother all but gave up the land in Livonia.

Having rejected peace proposals from its enemies, Ivan the Terrible found himself in a difficult position by 1578, when the Crimean Khanate devastated southern Muscovian territories and burnt down suburb(posad) of Moscow (see Russo-Crimean Wars), the drought and epidemics had fatally affected the economy, the policy of oprichnina had thoroughly disrupted the government, while the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had united with the Kingdom of Poland and acquired an energetic leader, Stefan Batory, supported by the Ottoman Empire (1576). Batory replied with a series of three offensives against Muscovy, trying to cut the Kingdom of Livonia from Muscovian territories. During his first offensive in 1579 with 22,000 men he retook Polotsk. During the second, in 1580, with a 29,000-strong army he took Velikie Luki, and in 1581 with a 100,000-strong army he started the Siege of Pskov. Frederick II had trouble continuing the fight against Muscovy unlike Sweden and Poland. He came to an agreement with John III of Sweden in 1580 giving him the titles in Livonia. That war would last from 1577 to 1582. Muscovy recognized Polish–Lithuanian control of Ducatus Ultradunensis only in 1582. After Magnus von Lyffland died in 1583, Poland invaded his territories in the Duchy of Courland and Frederick II decided to sell his rights of inheritance. Except for the island of Œsel, Denmark was out of the Baltic by 1585. In 1598 Polish Livonia was divided into:

- Wenden Voivodeship (województwo wendeńskie, Kieś)

- Dorpat Voivodeship (województwo dorpackie, Dorpat)

- Parnawa Voivodeship (województwo parnawskie, Parnawa)

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

During 1582–83 southern Estonia (Livonia) became part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Estonia in the Swedish Empire (1561–1710)

The Duchy of Estonia placed itself under Swedish rule in 1561 to receive protection against Russia and Poland as the Livonian Order lost their foothold in the Baltic provinces. Territorially it represented the northern part of present-day Estonia.

Livonia was conquered from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by 1629 in the Polish–Swedish War. By the Treaty of Oliva between the Commonwealth and Sweden in 1660 following the Northern Wars the Polish–Lithuanian king renounced all claims to the Swedish throne and Livonia was formally ceded to Sweden. Swedish Livonia represents the southern part of present-day Estonia and the northern part of present-day Latvia (Vidzeme region).

In 1631, Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden forced the nobility to grant the rural commoners greater autonomy. During his rule, in 1632, the first printing press, and the university was established in the city of Tartu.

Estonia in the Russian Empire (1710–1917)

Sweden's defeat by Russia in the Great Northern War resulted in the capitulation of Estonia and Livonia in 1710, confirmed by the Treaty of Nystad in 1721, and Russian rule was then imposed on what later became modern Estonia. Nonetheless, the legal system, Lutheran church, local and town governments, secondary and higher education continued mostly in German language until the late 19th century and partially until 1918.

Under the imperial Russian rule, from the 1720s to the First World War, in Estonia the local Baltic German minority continued to own most of the land and businesses, and dominated in all cities. The local German-speakers were Lutherans, and so were the vast majority of the Estonian population. Moravian Protestant missionaries made an impact in the eighteenth century, and translated the complete Bible into Estonian. Some Germans complained, the imperial government banned the Moravians from 1743 to 1764. A theological faculty opened at the University of Dorpat (Tartu), with German professors. The local German gentry controlled the local churches and rarely hired Estonian graduates, but they made their mark as intellectuals and Estonian nationalists. In the 1840s, there was a movement of Lutheran farmers into the Russian Orthodox Church. The czar discouraged them when he realized they were challenging the local authorities.[22] The German character of the Lutheran churches alienated many nationalists, who emphasized the secular in their subcultures. For example, choral societies offered a secular alternative to church music.[23]

By 1819, the Baltic provinces were the first in the Russian empire in which serfdom was abolished, enabling an increasing number of farmers to rent or purchase land, as well as triggering a wave of internal migration of landless rural Estonians into the growing cities. These moves created the economic foundation for the coming to life of the Estonian national identity, as the country was caught in a current of national awakening that began sweeping through Europe in the mid-19th century. The general population, as well as the students and faculty of the multicultural University of Tartu, were largely uninterested in the Russification programmes introduced by the imperial Russian central government in the 1890s.[24]

The Estophile enlightenment period (1750–1840)

Educated German immigrants and local Baltic Germans in Estonia, educated at German universities, introduced Enlightenment ideas of rational thinking, ideas that propagated freedom of thinking and brotherhood and equality. The French Revolution provided a powerful motive for the "enlightened" local upper class to create literature for the commoners.[25] The abolition of serfdom on in 1816 in southern Estonia (then Governorate of Livonia), and 1819 in northern Estonia (then Governorate of Estonia) by Emperor Alexander I of Russia gave rise to a debate as to the future fate of the Estonian-speaking population. Although many Baltic Germans regarded the future of the Estonians as being a fusion with the Germans, many other educated and Estophile Germans admired the ancient culture of the Estonians and their era of freedom before the conquests by Danes and Germans in the 13th century.[26] The Estophile Enlightenment Period formed the transition from religious Estonian literature to newspapers printed in Estonian for the general public.

National awakening

A cultural movement sprang forth to adopt the use of Estonian as the language of instruction in schools, all-Estonian song festivals were held regularly after 1869, and a national literature in Estonian developed. Kalevipoeg, Estonia's national epic, was published in 1861 in both Estonian and German.

1889 marked the beginning of the central government-sponsored policy of Russification. The impact of this was that many of the Baltic German legal institutions were either abolished or had to do their work in Russian – a good example of this is the University of Tartu.

As the Russian Revolution of 1905 swept through Estonia, the Estonians called for freedom of the press and assembly, for universal franchise, and for national autonomy. Estonian gains were minimal, but the tense stability that prevailed between 1905 and 1917 allowed Estonians to advance the aspiration of national statehood.

Road to the republic (1917–1920)

Estonia as a unified political entity first emerged after the Russian February Revolution of 1917. With the collapse of the Russian Empire in World War I, Russia's Provisional Government granted national autonomy to a unified Estonia in April. The Governorate of Estonia in the north (corresponding to the historic Danish Estonia) was united with the northern part of the Governorate of Livonia. Elections for a provisional parliament, Maapäev, was organized, with the Menshevik and Bolshevik factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party obtaining a part of the vote. On 5 November 1917, two days before the October Revolution in Saint Petersburg, Estonian Bolshevik leader Jaan Anvelt violently usurped power from the legally constituted Maapäev in a coup d'état, forcing the Maapäev underground.

In February, after the collapse of the peace talks between Soviet Russia and the German Empire, mainland Estonia was occupied by the Germans. Bolshevik forces retreated to Russia. Between the Russian Red Army's retreat and the arrival of advancing German troops, the Salvation Committee of the Estonian National Council Maapäev issued the Estonian Declaration of Independence[27] in Pärnu on 23 February 1918.

War of Independence

After the collapse of the short-lived puppet government of the United Baltic Duchy and the withdrawal of German troops in November 1918, an Estonian Provisional Government retook office. A military invasion by the Red Army followed a few days later, however, marking the beginning of the Estonian War of Independence (1918–1920). The Estonian army cleared the entire territory of Estonia of the Red Army by February 1919. On 5–7 April 1919 the Estonian Constituent Assembly was elected.

By the summer of 1919, Estonia had reached its largest territorial extent ever, having pushed the Red Army far beyond Estonia's borders on the Southern and Eastern fronts, with the assistance of the Northwestern army under the Estonian command in the east.

Victory

On 2 February 1920, the Treaty of Tartu was signed by the Republic of Estonia and the Russian SFSR. The terms of the treaty stated that Russia renounced in perpetuity all rights to the territory of Estonia.

The first Constitution of Estonia was adopted on 15 June 1920. The Republic of Estonia obtained international recognition and became a member of the League of Nations in 1921.

Interwar period (1920–1939)

The first period of independence lasted 22 years, beginning in 1918. Estonia underwent a number of economic, social, and political reforms necessary to come to terms with its new status as a sovereign state. Economically and socially, land reform in 1919 was the most important step. Large estate holdings belonging to the Baltic nobility were redistributed among farmers and especially among volunteers in the Estonian War of Independence. Estonia's principal markets became Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, and western Europe, with some exports to the United States and to the Soviet Union.

The first constitution of the Republic of Estonia, adopted in 1920, established a parliamentary form of government. The parliament (Riigikogu) consisted of 100 members elected for three-year terms. Between 1920 and 1934, Estonia had 21 governments.

A mass anticommunist and antiparliamentary Vaps Movement emerged in the 1930s.[28] In October 1933, a referendum on constitutional reform initiated by the Vaps Movement was approved by 72.7 percent.[28] The league spearheaded replacement of the parliamentary system with a presidential form of government and laid the groundwork for an April 1934 presidential election, which it expected to win. However, the Vaps Movement was thwarted by a pre-emptive self-coup on 12 March 1934, by then Head of State Konstantin Päts, who established his own authoritarian rule until a new constitution came to force in 1938. The parliament was not in session between 1934 and 1938, and the country was ruled by decree by Päts. The Vaps Movement was officially banned and finally disbanded in December 1935. On 6 May 1936, 150 members of the league went on trial and 143 of them were convicted to long-term prison sentences. They were granted an amnesty and freed in 1938, by which time the league had lost most of its popular support.

The interwar period was one of great cultural advancement.[29] Estonian language schools were established, and artistic life of all kinds flourished. One of the more notable cultural acts of the independence period, unique in western Europe at the time of its passage in 1925, was a guarantee of cultural autonomy to minority groups comprising at least 3,000 persons, including Jews (see history of the Jews in Estonia). Historians see the lack of any bloodshed after a nearly "700-year German rule" as indication that it must have been mild by comparison.

Estonia had pursued a policy of neutrality, but it was of no consequence after the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August 1939. In the agreement, the two great powers agreed to divide up the countries situated between them (Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland), with Estonia falling in the Soviet "sphere of influence". After the invasion of Poland, the Orzeł incident took place when Polish submarine ORP Orzeł looked for shelter in Tallinn but escaped after the Soviet Union attacked Poland on 17 September. Estonia's lack of will and/or inability to disarm and intern the crew caused the Soviet Union to accuse Estonia of "helping them escape" and claim that Estonia was not neutral. On 24 September 1939, the Soviet Union threatened Estonia with war unless provided with military bases in the country—an ultimatum with which the Estonian government complied.

World War II (1939–1944)

Following the conclusion of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the Soviet invasion of Poland, warships of the Red Navy appeared off Estonian ports on 24 September 1939, and Soviet bombers began a threatening patrol over Tallinn and the nearby countryside.[30] Moscow demanded Estonia assent to an agreement which allowed the USSR to establish military bases and station 25,000 troops on Estonian soil for the duration of the European war.[31] The government of Estonia accepted the ultimatum, signing the corresponding agreement on 28 September 1939.

Incorporation in the Soviet Union (1940)

The Republic of Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union in June 1940.[32][33][34]

On 12 June 1940, the order for a total military blockade of Estonia by the Soviet Baltic Fleet was given.[35][36]

On 14 June 1940, while the world's attention was focused on the fall of Paris to Nazi Germany a day earlier, the Soviet military blockade of Estonia went into effect, and two Soviet bombers downed Finnish passenger airplane Kaleva flying from Tallinn to Helsinki carrying three diplomatic pouches from the U.S. legations in Tallinn, Riga and Helsinki. US Foreign Service employee Henry W. Antheil Jr. was killed in the crash.[37]

On 16 June 1940, the Soviet Union invaded Estonia.[38] Molotov accused the Baltic states of conspiracy against the Soviet Union and delivered an ultimatum to Estonia for the establishment of a government approved of by the Soviets.

The Estonian government decided, given the overwhelming Soviet force both on the borders and inside the country, not to resist, to avoid bloodshed and open war.[39] Estonia accepted the ultimatum, and the statehood of Estonia de facto ceased to exist as the Red Army exited from their military bases in Estonia on 17 June. The following day, some 90,000 additional troops entered the country. The military occupation of the Republic of Estonia was rendered official by a communist coup d'état supported by the Soviet troops,[40] followed by parliamentary elections where all but pro-Communist candidates were outlawed. The newly elected parliament proclaimed Estonia a Socialist Republic on 21 July 1940 and unanimously requested Estonia to be accepted into the Soviet Union. Those who had fallen short of the "political duty" of voting Estonia into the USSR, who had failed to have their passports stamped for so voting, were allowed to be shot in the back of the head by Soviet tribunals.[41] Estonia was formally annexed into the Soviet Union on 6 August and renamed the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic.[42] In 1979, the European Parliament would condemn "the fact that the occupation of these formerly independent and neutral States by the Soviet Union occurred in 1940 following the Molotov/Ribbentrop pact, and continues," and sought to help restore Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian independence through political means.[43]

The Soviet authorities, having gained control over Estonia, immediately imposed a regime of terror. During the first year of Soviet occupation (1940–1941) over 8,000 people, including most of the country's leading politicians and military officers, were arrested. About 2,200 of the arrested were executed in Estonia, while most of the others were moved to Gulag prison camps in Russia, from where very few were later able to return alive. On 14 June 1941, when mass deportations took place simultaneously in all three Baltic countries, about 10,000 Estonian civilians were deported to Siberia and other remote areas of the Soviet Union, where nearly half of them later perished. Of the 32,100 Estonian men who were forcibly relocated to Russia under the pretext of mobilisation into the Soviet army after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, nearly 40 percent died within the next year in the so-called "labour battalions" of hunger, cold and overworking. During the first Soviet occupation of 1940–41 about 500 Jews were deported to Siberia.

Estonian graveyards and monuments were destroyed. Among others, the Tallinn Military Cemetery had the majority of gravestones from 1918 to 1944 destroyed by the Soviet authorities, and this graveyard became reused by the Red Army.[44] Other cemeteries destroyed by the authorities during the Soviet era in Estonia include Baltic German cemeteries established in 1774 (Kopli cemetery, Mõigu cemetery) and the oldest cemetery in Tallinn, from the 16th century, Kalamaja cemetery.

Many countries including the United States did not recognize the seizure of Estonia by the USSR. Such countries recognized Estonian diplomats and consuls who still functioned in many countries in the name of their former governments. These aging diplomats persisted in this anomalous situation until the ultimate restoration of Baltic independence.

Ernst Jaakson, the longest-serving foreign diplomatic representative to the United States, served as vice-consul from 1934, and as consul general in charge of the Estonian legation in the United States from 1965 until reestablishment of Estonia's independence. On 25 November 1991, he presented credentials as Estonian ambassador to the United States.[45]

Occupation of Estonia by Nazi Germany (1941–1944)

.jpg.webp)

After Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, and the Wehrmacht reached Estonia in July 1941, most Estonians greeted the Germans with relatively open arms and hoped to restore independence. But it soon became clear that sovereignty was out of the question. Estonia became a part of the German-occupied "Ostland". A Sicherheitspolizei was established for internal security under the leadership of Ain-Ervin Mere. The initial enthusiasm that accompanied the liberation from Soviet occupation quickly waned as a result, and the Germans had limited success in recruiting volunteers. The draft was introduced in 1942, resulting in some 3,400 men fleeing to Finland to fight in the Finnish Army rather than join the Germans. Finnish Infantry Regiment 200 (Estonian: soomepoisid) was formed out of Estonian volunteers in Finland. With the Allied victory over Germany becoming certain in 1944, the only option to save Estonia's independence was to stave off a new Soviet invasion of Estonia until Germany's capitulation.

By January 1944, the front was pushed back by the Soviet Army almost all the way to the former Estonian border. Narva was evacuated. Jüri Uluots, the last legitimate prime minister of the Republic of Estonia (according to the Constitution of the Republic of Estonia) prior to its fall to the Soviet Union in 1940, delivered a radio address that implored all able-bodied men born from 1904 through 1923 to report for military service. (Before this, Uluots had opposed Estonian mobilization.) The call drew support from all across the country: 38,000 volunteers jammed registration centers.[46] Several thousand Estonians who had joined the Finnish army came back across the Gulf of Finland to join the newly formed Territorial Defense Force, assigned to defend Estonia against the Soviet advance. It was hoped that by engaging in such a war Estonia would be able to attract Western support for the cause of Estonia's independence from the USSR and thus ultimately succeed in achieving independence.[47]

The initial formation of the volunteer SS Estonian legion created in 1942 was eventually expanded to become a full-sized conscript division of the Waffen-SS in 1944, the 20th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS. The Estonian units saw action defending the Narva line throughout 1944.

As the Germans started to retreat on 18 September 1944, Jüri Uluots, the last Prime Minister of the Estonian Republic prior to Soviet occupation, assumed the responsibilities of president (as dictated in the Constitution) and appointed a new government while seeking recognition from the Allies. On 22 September 1944, as the last German units pulled out of Tallinn, the city was re-occupied by the Soviet Red Army. The new Estonian government fled to Stockholm, Sweden, and operated in exile from 1944 until 1992, when Heinrich Mark, the prime minister of the Estonian government in exile acting as president, presented his credentials to incoming president Lennart Meri.

The Holocaust in Estonia

The process of Jewish settlement in Estonia began in the 19th century, when in 1865 Russian Tsar Alexander II granted them the right to enter the region. The creation of the Republic of Estonia in 1918 marked the beginning of a new era for the Jews. Approximately 200 Jews fought in combat for the creation of the Republic of Estonia, and 70 of these men were volunteers. From the very first days of its existence as a state, Estonia showed tolerance towards all the peoples inhabiting its territories. On 12 February 1925, the Estonian government passed a law pertaining to the cultural autonomy of minority peoples. The Jewish community quickly prepared its application for cultural autonomy. Statistics on Jewish citizens were compiled. They totaled 3,045, fulfilling the minimum requirement of 3,000. In June 1926 the Jewish Cultural Council was elected and Jewish cultural autonomy was declared. Jewish cultural autonomy was of great interest to the global Jewish community. The Jewish National Endowment presented the Government of the Republic of Estonia with a certificate of gratitude for this achievement.[48]

There were, at the time of Soviet occupation in 1940, approximately 2,000 Estonian Jews. Many Jewish people were deported to Siberia along with other Estonians by the Soviets. It is estimated that 500 Jews suffered this fate. With the invasion of the Baltics, it was the intention of the Nazi government to use the Baltic countries as their main area of mass genocide. Consequently, Jews from countries outside the Baltics were shipped there to be exterminated. Out of the approximately 4,300 Jews in Estonia prior to the war, between 1,500 and 2,000 were entrapped by the Nazis,[49] and an estimated 10,000 Jews were killed in Estonia after having been deported to camps there from Eastern Europe.[48]

There have been seven ethnic Estonians – Ralf Gerrets, Ain-Ervin Mere, Jaan Viik, Juhan Jüriste, Karl Linnas, Aleksander Laak and Ervin Viks – who have faced trials for crimes against humanity since the reestablishment of Estonian independence and the formation of the Estonian International Commission for Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity.[50] Markers were put in place for the 60th anniversary of the mass executions that were carried out at the Lagedi, Vaivara[51] and Klooga (Kalevi-Liiva) camps in September 1944.[52]

Fate of other minorities during and after World War II

The Baltic Germans had voluntarily evacuated to Germany (in accordance with Hitler's order) following the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939.

Almost all the remaining Estonian Swedes fled Aiboland in August 1944, often in their small boats to the Swedish island of Gotland.

The Russian minority grew significantly in numbers during the postwar era.

Soviet Estonia (1944–1991)

Stalinism

In World War II Estonia had suffered huge losses. Ports had been destroyed, and 45% of industry and 40% of the railways had become damaged. Estonia's population had decreased by one-fifth, about 200,000 people.[53] Some 10% of the population (over 80,000 people) had fled to the West between 1940 and 1944, first to countries such as Sweden and Finland and then to other western countries, often by refugee ships such as the SS Walnut. More than 30,000 soldiers had been killed in action. In 1944 Russian air raids had destroyed Narva and one-third of the residential area in Tallinn. By the late autumn of 1944, Soviet forces had ushered in a second phase of Soviet rule on the heels of the German troops withdrawing from Estonia, and followed it up by a new wave of arrests and executions of people considered disloyal to the Soviets.

An anti-Soviet pro-Nazi guerrilla movement known as the Metsavennad ("Forest Brothers") developed in the countryside, reaching its zenith in 1946–48. It is hard to tell how many people were in the ranks of the Metsavennad; however, it is estimated that at different times there could have been about 30,000–35,000 people. Probably the last Forest Brother was caught in September 1978, and killed himself during his apprehension.

In March 1949, 20,722 people (2.5% of the population) were deported to Siberia. By the beginning of the 1950s, the occupying regime had suppressed the resistance movement.

After the war the Communist Party of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (ECP) became the pre-eminent organization in the republic. The ethnic Estonian share in the total ECP membership decreased from 90% in 1941 to 48% in 1952.

_Johannes_K%C3%A4bin.jpg.webp)

Khrushchev era

After Stalin's death, Communist Party membership vastly expanded its social base to include more ethnic Estonians. By the mid-1960s, the percentage of ethnic Estonian membership stabilized near 50%. On the eve of perestroika the ECP claimed about 100,000 members; less than half were ethnic Estonians and they totalled less than 7% of the country's population.

One positive aspect of the post-Stalin era in Estonia was the regranting of permission in the late 1950s for citizens to make contact with foreign countries. In the 1960s, Estonians were thus able to start watching Finnish television. This electronic "window to the West" afforded Estonians more information on current world affairs and more access to contemporary Western culture and thought than any other group in the Soviet Union.

Brezhnev era

In the late 1970s, Estonian society grew increasingly concerned about the threat of cultural Russification to the Estonian language and national identity. By 1981, Russian was taught in the first grade of Estonian-language schools and was also introduced into Estonian pre-school teaching.

Moscow Olympic Games of 1980

Tallinn was selected to host the sailing events at the 1980 Summer Olympics, which led to controversy[54] since many governments had not de jure recognized ESSR as part of the USSR. During the preparations to the Olympics, sports buildings were built in Tallinn, along with other general infrastructure and broadcasting facilities. This wave of investment included Tallinn Airport, Hotell Olümpia, Tallinn TV Tower, Pirita Yachting Centre and Linnahall.[55]

Andropov and Chernenko era

On 10 November 1982, Leonid Brezhnev died and was succeeded by Yuri Andropov, the former head of the KGB. Andropov introduced limited economic reforms and established an anti-corruption program. On 9 February 1984, Andropov died and was succeeded by Konstantin Chernenko who in turn died on 10 March 1985.[56]

Gorbachev era

By the beginning of the Gorbachev era, concern over the cultural survival of the Estonian people had reached a critical point. The ECP remained stable in the early perestroika years but waned in the late 1980s. Other political movements, groupings and parties moved to fill the power vacuum. The first and most important was the Estonian Popular Front, established in April 1988 with its own platform, leadership and broad constituency. The Greens and the dissident-led Estonian National Independence Party soon followed.

Restoration of de facto independence

The Estonian Sovereignty Declaration was issued on 16 November 1988.[57] By 1989 the political spectrum had widened, and new parties were formed and re-formed almost daily. The republic's Supreme Soviet transformed into an authentic regional lawmaking body. This relatively conservative legislature passed an early declaration of sovereignty (16 November 1988); a law on economic independence (May 1989) confirmed by the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union that November; a language law making Estonian the official language (January 1989); and local and republic election laws stipulating residency requirements for voting and candidacy (August, November 1989).

Despite the emergence of the Popular Front and the Supreme Soviet as a new lawmaking body, since 1989 the different segments of the indigenous Estonian population had been politically mobilized by different and competing actors. The Popular Front's proposal to declare the independence of Estonia as a new, so-called "third republic" whose citizens would be all those living there at the moment, found less and less support over time.

A grassroots Estonian Citizens' Committees Movement launched in 1989 with the objective of registering all pre-war citizens of the Republic of Estonia and their descendants in order to convene a Congress of Estonia. Their emphasis was on the illegal nature of the Soviet system and that hundreds of thousands of inhabitants of Estonia had not ceased to be citizens of the Estonian Republic which still existed de jure, recognized by the majority of Western nations. Despite the hostility of the mainstream official press and intimidation by Soviet Estonian authorities, dozens of local citizens' committees were elected by popular initiative all over the country. These quickly organized into a nationwide structure, and by the beginning of 1990 over 900,000 people had registered themselves as citizens of the Republic of Estonia.

The spring of 1990 saw two free elections and two alternative legislatures developed in Estonia. On 24 February 1990, the 464-member Congress of Estonia (including 35 delegates of refugee communities abroad) was elected by the registered citizens of the republic. The Congress of Estonia convened for the first time in Tallinn 11–12 March 1990, passing 14 declarations and resolutions. A 70-member standing committee (Eesti Komitee) was elected with Tunne Kelam as its chairman.

In March 1991 a referendum was held on the issue of independence. This was somewhat controversial, as holding a referendum could be taken as signalling that Estonian independence would be established rather than "re"-established. There was some discussion about whether it was appropriate to allow the Russian immigrant minority to vote, or if this decision should be reserved exclusively for citizens of Estonia. In the end all major political parties backed the referendum, considering it most important to send a strong signal to the world. To further legitimise the vote, all residents of Estonia were allowed to participate. The result vindicated these decisions, as the referendum produced a strong endorsement for independence. Turnout was 82%, and 64% of all possible voters in the country backed independence, with only 17% against.

Although the majority of Estonia's large Russian-speaking diaspora of Soviet-era immigrants did not support full independence, they were divided in their goals for the republic. In March 1990 some 18% of Russian speakers supported the idea of a fully independent Estonia, up from 7% the previous autumn, and by early 1990 only a small minority of ethnic Estonians were opposed to full independence.

In the 18 March 1990, elections for the 105-member Supreme Soviet, all residents of Estonia were eligible to participate, including all Soviet-era immigrants from the U.S.S.R. and approximately 50,000 Soviet troops stationed there. The Popular Front coalition, composed of left and centrist parties and led by former Central Planning Committee official Edgar Savisaar, gained a parliamentary majority.

On 8 May 1990, the Supreme Council of the Republic of Estonia (renamed the previous day) changed the name to the Republic of Estonia. Through a strict, non-confrontational policy in pursuing independence, Estonia managed to avoid the violence which Latvia and Lithuania incurred in the bloody January 1991 crackdowns and in the border customs-post guard murders that summer. During the attempted August coup in the U.S.S.R., Estonia was able to maintain constant operation and control of its telecommunications facilities, thereby offering the West a clear view into the latest developments and serving as a conduit for swift Western support and recognition of Estonia's own "confirmation" of independence on 20 August 1991. 20 August remains a national holiday in Estonia because of this. Russia as a republic of the U.S.S.R. formally recognized Estonia's independence on 25 August 1991 and called on the U.S.S.R. union government to follow suit.[58] United States intentionally delayed recognition to 2 September,[59] and the State Council of the Soviet Union issued its recognition on 6 September.

Since the debates about whether the future independent Estonia would be established as a new republic or a continuation of the first republic were not yet complete by the time of the August coup, while the members of the Supreme Soviet generally agreed that independence should be declared rapidly, a compromise was hatched between the two main sides: instead of "declaring" independence, which would imply a new start, or explicitly asserting continuity, the declaration would "confirm" Estonia as a state independent of the Soviet Union, and willing to reestablish diplomatic relations of its own accord. The text of the statement was in Estonian and only a few paragraphs in length.[60]

After more than three years of negotiations, on 31 August 1994, the armed forces of Russia withdrew from Estonia. Since fully regaining independence Estonia has had sixteen governments with ten prime ministers: Mart Laar, Andres Tarand, Tiit Vähi, Mart Siimann, Siim Kallas, Juhan Parts, Andrus Ansip, Taavi Rõivas, Jüri Ratas and Kaja Kallas. The PMs of the interim government (1990–1992) were Edgar Savisaar and Tiit Vähi.

Since the last Russian troops left in 1994, Estonia has been free to promote economic and political ties with Western Europe. Estonia opened accession negotiations with the European Union in 1998 and joined in 2004, shortly after becoming a member of NATO.

Contemporary Estonian government (1992–present)

On 28 June 1992, Estonian voters approved the constitutional assembly's draft constitution and implementation act, which established a parliamentary government with a president as chief of state and with a government headed by a prime minister. The Riigikogu, a unicameral legislative body, is the highest organ of state authority. It initiates and approves legislation sponsored by the prime minister. The prime minister has full responsibility and control over his cabinet.

Meri presidency and Laar premiership (1992–2001)

Parliamentary and presidential elections were held on 20 September 1992. Approximately 68% of the country's 637,000 registered voters cast ballots. Lennart Meri, an outstanding writer and former Minister of Foreign Affairs, won this election and became president. He chose 32-year-old historian and Christian Democratic Party founder Mart Laar as prime minister.

In February 1992, and with amendments in January 1995, the Riigikogu renewed Estonia's 1938 citizenship law, which also provides equal civil protection to resident aliens. Elected on an ambitious programme of reform, Mart Laar's cabinet took several decisive measures (shock therapy). Fast privatization was pursued and the role of the state in the economy as well as in the social affairs was reduced dramatically. After an initial steep decline in GDP, the Estonian economy started to grow again in 1995. Changes came with a social price: the average life expectancy in Estonia in 1994 was lower than in Belarus, Ukraine and even Moldova.[61] Among the vulnerable sectors of society, the radical reforms sparked an outrage. In January 1993, a pensioners' demonstration took place in Tallinn, as pensioners felt it was impossible to live with a pension as low as the one in effect at the time (260 EEK (around 20 EUR) a month[62]). The meeting was aggressive and demonstrators attacked the minister of social affairs Marju Lauristin.[63]

On 28 September 1994, the MS Estonia sank as the ship was crossing the Baltic Sea, en route from Tallinn, Estonia, to Stockholm, Sweden. The disaster claimed the lives of 852 people (501 of them were Swedes[64]), being one of the worst maritime disasters of the 20th century.[65]

The opposition won the 1995 election, but to a large extent continued with the previous governments' policies.

In 1996, Estonia ratified a border agreement with Latvia and completed work with Russia on a technical border agreement. President Meri was re-elected in free and fair indirect elections in August and September in 1996. During parliamentary elections in 1999, the seats in the Riigikogu were divided as follows: the Estonian Centre Party received 28, the Pro Patria Union 18, the Estonian Reform Party 18, the People's Party Moderates (election cartel between Moderates and People's Party) 17, Coalition Party 7, Country People's Party (now People's Union of Estonia) 7, and the United People's Party's electoral cartel 6 seats. Pro Patria Union, the Reform Party, and the Moderates formed a government with Mart Laar as prime minister, whereas the Centre Party with the Coalition Party, People's Union, United People's Party, and members of parliament who were not members of factions formed the opposition in the Riigikogu.

The 1999 Parliamentary election, with a 5% threshold and no electoral cartel allowed, resulted in a disaster for the Coalition Party, which achieved only seven seats together with two of its smaller allies. Estonian Ruralfolk Party, which participated the election on its own list, obtained seven seats as well.

The programme of Mart Laar's government was signed by Pro Patria Union, the Reform Party, the Moderates, and the People's Party. The latter two merged soon after, so Mart Laar's second government is widely known as Kolmikliit, or the Tripartite coalition. Notwithstanding the different political orientation of the ruling parties, the coalition stayed united until Laar resigned in December 2001, after the Reform Party had broken up the same coalition in Tallinn municipality, making opposition leader Edgar Savisaar the new mayor of Tallinn. After the resignation of Laar, the Reform Party and Estonian Centre Party formed a coalition that lasted until the next parliamentary election, in 2003.

The Moderates joined with the People's Party on 27 November 1999, forming the People's Party Moderates.

Rüütel presidency and Siim Kallas government (2001–2002)

In fall 2001 Arnold Rüütel became the President of the Republic of Estonia, and in January 2002 Prime Minister Laar stepped down. On 28 January 2002, the new government was formed from a coalition of the centre-right Estonian Reform Party and the more left wing Centre Party, with Siim Kallas from the Reform Party of Estonia as Prime Minister.[66]

Juhan Parts government (2003-2005)

Following parliamentary elections in 2003, the seats were allocated as follows (the United People's Party failed to meet the 5% threshold):

- Centre Party 28,

- Res Publica 28,

- Reform Party 19,

- People's Union 13,

- Pro Patria Union 7,

- People's Party Moderates 6

Voter turnout was higher than expected at 58%.[67] The results saw the Centre Party win the most votes, but they were only 0.8% ahead of the new Res Publica party.[68] As a result, both parties won 28 seats, which was a disappointment for the Centre Party who had expected to win the most seats.[69] Altogether the right of centre parties won 60 seats, compared to only 41 for the left wing, and so were expected to form the next government.[66][70] Both the Centre and Res Publica parties said that they should get the chance to try and form the next government,[71] while ruling out any deal between themselves.[72] President Rüütel had to decide who he should nominate as Prime Minister and therefore be given the first chance at forming a government.[72] On 2 April he invited the leader of the Res Publica party, Juhan Parts, to form a government,[73] and after negotiations a coalition government composed of Res Publica, the Reform Party and the People's Union of Estonia was formed on 10 April.[73]

On 14 September 2003, following negotiations that began in 1998, the citizens of Estonia were asked in a referendum whether or not they wished to join the European Union. With 64% of the electorate turning out, the referendum passed with a 66.83% margin in favor, 33.17% against. Accession to the EU took place on 1 May of the following year.

In February 2004 the People's Party Moderates renamed themselves the Social Democratic Party of Estonia.[74]

Estonia joined NATO on 29 March 2004.[75]

On 8 May 2004, a defection of several Centre Party members to form a new party, the Social Liberal Party, over a row concerning the Centrists' "no" stance to joining the European Union changed the allocation of the seats in the Riigikogu. Social-liberals had eight seats, but a hope to form a new party disappeared by 10 May 2005, because most members in the social-liberal group joined other parties.

On 24 March Prime Minister Juhan Parts announced his resignation following a vote of no confidence in the Riigikogu against Minister of Justice Ken-Marti Vaher, which was held on 21 March. The result was 54 pro (Social Democrats, Social Liberals, People's Union, Pro Patria Union and Reform Party) with no against or neutral MPs. 32 MPs (Res Publica and Centre Party) did not take part.[76]

Andrus Ansip government (2005-2014)

On 4 April 2005, President Rüütel nominated Reform party leader Andrus Ansip as Prime Minister designate and asked him to form a new government, the eighth in twelve years. Ansip formed a government out of a coalition of his Reform Party with the People's Union and the Centre Party. Approval by the Riigikogu, which by law must decide within 14 days of his nomination, came on 12 April 2005.[77] Ansip was backed by 53 out of 101 members of the Estonian parliament. Forty deputies voted against his candidature. The general consensus in the Estonian media seems to be that the new cabinet, on the level of competence, is not necessarily an improvement over the old one.

On 18 May 2005, Estonia signed a border treaty with the Russian Federation in Moscow.[78] The treaty was ratified by the Riigikogu on 20 June 2005. However, in the end of June the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs informed that it did not intend to become a party to the border treaty and did not consider itself bound by the circumstances concerning the object and the purposes of the treaty because the Riigikogu had attached a preambule to the ratification act that referenced earlier documents that mentioned the Soviet occupation and the uninterrupted legal continuity of the Republic of Estonia during the Soviet period. The issue remains unsolved and is the focus of European-level discussions.

On 4 April 2006, Fatherland Union and Res Publica decided to form a united right-conservative party. The two parties joining was approved on 4 June by both parties in Pärnu. The joined party name is Isamaa ja Res Publica Liit (Union of Pro Patria and Res Publica).[79]

In September 2006, Toomas Hendrik Ilves was elected as the new president of Estonia. He defeated in the Electoral Assembly incumbent one-term president Arnold Rüütel.[80]

2007 election

The 2007 parliamentary elections have shown an improvement in the scores of the Reform Party, gaining 12 seats and reaching 31 MPs; the Centre Party held, while the unified right-conservative Union of Pro Patria and Res Publica lost 16. Socialdemocrats gained 4 seats, while the Greens entered the Parliaments with 7 seats, at the expense of the agrarian People's Union which lost 6. The new configuration of the Estonian Parliament shows a prevalence of centre-left parties. The Centre Party, led by the mayor of Tallinn Edgar Savisaar, has been increasingly excluded from collaboration, since his open collaboration with Putin's United Russia party, real estate scandals in Tallinn,[81] and the Bronze Soldier controversy, considered as a deliberate attempt of splitting the Estonian society by provoking the Russian minority.[82] The lack of a concrete possibility for government alternance in Estonia has been quoted as a concern.[83]

Estonia and the European Union

On 14 September 2003, following negotiations that began in 1998, the citizens of Estonia were asked in a referendum whether or not they wished to join the European Union. With 64% of the electorate turning out the referendum passed with a 66.83% margin in favor, 33.17% against.[84] Accession to the EU took place the following year, on 1 May 2004. Estonia became Schengen area member on 21 December 2007[85]

In its first European Parliament elections in 2004, Estonia elected three MEPs for the Social Democratic Party (PES), while the governing Res Publica Party and People's Union polled poorly, not being able to gain any of the other three MEP posts. The voter turnout in Estonia was one of the lowest of all member countries, at only 26.8%. A similar trend was visible in most of the new member states that joined the EU in 2004.

The European Parliament election of 2009 in Estonia scored a 43.9% turnout – about 17.1% higher than during the previous election, and slightly above the European average of 42.94%. Six seats were up for taking in this election: two of them were won by the Estonian Centre Party. Estonian Reform Party, Union of Pro Patria and Res Publica, Social Democratic Party and an independent candidate Indrek Tarand (who gathered the support of 102,460 voters, only 1,046 votes less than the winner of the election) all won one seat each. The success of independent candidates has been attributed both to general disillusionment with major parties and the use of closed lists which rendered voters incapable of casting a vote for specific candidates in party lists.

On 1 January 2011 Estonia adopted the euro.[86] The enlargement of the eurozone was hailed as a good sign in a period of global financial crisis. However, the government cut down public service salaries; the only opposition, in the absence of organised unions, came from Estonian teachers, whose salary cuts were therefore limited.[83]

Estonian euro coins entered circulation on 1 January 2011. Estonia was the fifth of ten states that joined the EU in 2004, and the first ex-Soviet republic to join the eurozone. Of the ten new member states, Estonia was the first to unveil its design. It originally planned to adopt the euro on 1 January 2007; however, it did not formally apply when Slovenia did, and officially changed its target date to 1 January 2008, and later, to 1 January 2011.[87] On 12 May 2010 the European Commission announced that Estonia had met all criteria to join the eurozone.[88] On 8 June 2010, the EU finance ministers agreed that Estonia would be able to join the euro on 1 January 2011.[89] On 13 July 2010, Estonia received the final approval from the ECOFIN to adopt the euro as from 1 January 2011. On the same date the exchange rate at which the kroon would be exchanged for the euro (€1 = 15.6466 krooni) was also announced. On 20 July 2010, mass production of Estonian euro coins began in the Mint of Finland.[90]

Being a member of the eurozone, NATO and the European Union, Estonia is the most integrated in Western European organizations of all Nordic states.[91]

Estonia–Russia relations in the late 2000s

_02.jpg.webp)

Estonia–Russia relations remain tense. According to the Estonian Internal Security Service, Russian influence operations in Estonia form a complex system of financial, political, economic and espionage activities in the Republic of Estonia for the purposes of influencing Estonia's political and economic decisions in ways considered favourable to the Russian Federation and conducted under the sphere-of-influence doctrine known as near abroad. According to the Centre for Geopolitical Studies, the Russian information campaign, which the centre characterises as a "real mud-throwing" exercise, had provoked a split in Estonian society amongst Russian speakers, inciting some to riot over the relocation of the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn, a cenotaph commemorating the soldiers killed in World War II.[92] Estonia regarded the 2007 cyberattacks on Estonia as an information operation intended to influence the decisions and actions of the Estonian government. While Russia denied any direct involvement in the attacks, hostile rhetoric in the media from the political elite influenced people to attack.[93] Following the 2007 cyber-attacks, the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE) was established in Tallinn.[94]

From 2011 to present

In August 2011, President Toomas Hendrik Ilves was re-elected in a vote in parliament for the second five-year term.[95] Center-right Reform Party was the biggest party in 2011 and 2015 parliamentary elections.[96] Estonian prime minister Andrus Ansip resigned in March 2014, after nine years in office since 2005. He wanted his successor to lead the Reform Party into 2015 elections.[97] In April 2014, Taavi Rõivas of the Reform party became new prime minister.[98] In October 2016, Estonia's parliament elected Kersti Kaljulaid as the new president of Estonia. The role of president is a largely ceremonial.[99] In November 2016, chairman of the Centre Party Jüri Ratas became the new prime minister of Estonia, after Prime Minister Taavi Rõivas had lost a parliamentary vote on confidence.[100]

In March 2019, Estonian parliamentary election the center-right opposition party Reform won the elections and ruling Centre was the second. Far-right Conservative People's Party of Estonia (EKRE) came third.[101] After the election prime minister Ratas formed a new three-party coalition government with far-right EKRE and rightwing Isamaa[102] In January 2021, prime minister Jüri Ratas resigned over a corruption scandal in his Centre Party.[103] The leader of Reform party Kaja Kallas formed a new two-party coalition government between the Reform and Center parties. She was the first female prime minister of Estonia. Her father Siim Kallas was the founder of the Reform party and he was prime minister of Estonia in 2002–2003.[104][105]

Female leadership 2021

After the formation of the new government in 2021, Estonia was the only country in the world that was led by elected women as the head of state and as the head of government: both the president, Kersti Kaljulaid, and prime minister, Kaja Kallas, were female.[106] In the cabinet of Kaja Kallas there were also several women in other key positions, both foreign minister and finance minister were female.[107] However, Mr. Alar Karis was sworn in as Estonia's sixth President on October 11, 2021.[108]

Since 2022

In July 2022, Prime Minister Kaja Kallas formed a new three-party coalition by her liberal Reform Party, the Social Democrats and the conservative Isamaa party. Her previous government had lost its parliamentary majority after the center-left Center Party left the coalition.[109]

In March 2023, the Reform party, led by Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, won the parliamentary election, taking 31,4% of the vote. Far-right Conservative People's Party came second with 16,1 % and the third was the Centre Party with 15% of the vote.[110] In April 2023, Kallas formed her third government, which included in addition to Reform Party, also the liberal Estonia 200 and the Social Democratic (SDE) parties.[111]

Time line

|

See also

- Bishopric of Dorpat

- Dissolution of the Soviet Union

- German occupation of Estonia during World War II

- Hanseatic League

- History of Denmark

- History of Europe

- History of Finland

- History of Germany

- History of Latvia

- History of Lithuania

- History of Russia

- History of Sweden

- History of the European Union

- List of rulers of Estonia

- Livonian Crusade

- Livonian Order

- Politics of Estonia

- President of Estonia

- President-Regent

- Prime Minister of Estonia

- Soviet Union

- Timeline of Tallinn

- Ungannians

- Vironians

- Women in Estonia

References

- ↑ Subrenat 2004, p. 24

- 1 2 Mäesalu et al. 2004

- ↑ Background Notes, Estonia, September 1997. 1997.

- ↑ Subrenat 2004

- ↑ Subrenat 2004, p. 26

- ↑ Meri, Lennart (1976). Hõbevalge: Reisikiri tuultest ja muinasluulest. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat.

- ↑ Subrenat 2004, pp. 28–31

- ↑ Marcantonio, Angela (2002). The Uralic Language Family: Facts, myths and statistics. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. pp. 21–23. ISBN 0-631-23170-6.

- ↑ Jones & Pennick 1995, p. 195

- ↑ Jones & Pennick 1995, p. 179

- ↑ Cassiodorus; Hodgkin, Thomas (1886). The Letters of Cassiodorus: Being a condensed translation of the Variae epistolae of Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator. London: Frowde. p. 265. ISBN 1-152-37425-7.

- ↑ Abercromby, John (1898). The pre- and proto-historic Finns, both eastern and western: with the magic songs of the west Finns. London: D. Nutt. p. 141. ISBN 0-404-53592-5.

- ↑ Raun, Toivo U. (2001). Estonia and the Estonians. Stanford, California: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University. p. 11. ISBN 0-8179-2852-9.

- ↑ Christiansen, Eric (1997). The Northern Crusades (2nd ed.). London, England: Penguin. p. 93. ISBN 0-14-026653-4.

- ↑ "Salmonsens konversationsleksikon / 2/7" (in Danish). Project Runeberg. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Harrison, Dick (2005). Gud vill det! – Nordiska korsfarare under medeltid (in Swedish). Ordfront. p. 573. ISBN 978-91-7441-373-1.

- ↑ Reuter, Timothy (1995). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 6, C.1300-c.1415. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36290-0.

- ↑ Jokipii, Mauno, ed. (1992). Baltisk kultur och historia (in Swedish). Bonniers. p. 188. ISBN 91-34-51207-1.

- ↑ Krista Kodres, "Church and art in the First Century of the reformation in Estonia: Towards Lutheran orthodoxy," Scandinavian Journal of History (2003) 28#3 pp 187–203. online

- ↑ Harrison, Rachelle (June 2000). "Protestant Reformation in the Baltic". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Kenneth Scott Latourette, Christianity in a Revolutionary Age (195) 197–98

- ↑ Hank Johnston, "Religion and Nationalist Subcultures in the Baltics," Journal of Baltic Studies (1992) 23#2 pp 133–148.

- ↑ Neil Taylor (2008). Baltic Cities. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9781841622477.

- ↑ Miljan, Toivo (2004). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 313. ISBN 0-8108-4904-6.

- ↑ Subrenat 2004, p. 84

- ↑ "Estonian Declaration of Independence". www.president.ee. Estonian National Council. 24 February 1918. Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- 1 2 "Vaps". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Bennich-Björkman, L. (9 December 2007). Political Culture under Institutional Pressure: How Institutional Change Transforms Early Socialization. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-60996-9.

- ↑ "RUSSIA: Moscow's Week". Time. 9 October 1939. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Smith et al. 2002, p. 24

- ↑ The World Book Encyclopedia. Chicago, IL: World Book. 2003. ISBN 0-7166-0103-6.

- ↑ O'Connor, Kevin J. (2003). The History of the Baltic States. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32355-0.

- ↑ "Molotovi–Ribbentropi pakt ja selle tagajärjed" (in Estonian). Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 22 August 2006. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007.

- ↑ "Kaleva-koneen tuhosta uutta tietoa". www.mil.fi (in Finnish). Finnish Defence Forces. 14 June 2005. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "documents published" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. from the State Archive of the Russian Navy

- ↑ Johnson, Eric A.; Hermann, Anna (2007). "The Last Flight from Tallinn" (PDF). American Foreign Service Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Five Years of Dates". Time. 24 June 1940. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Smith et al. 2002, p. 19

- ↑ Subrenat 2004

- ↑ "Russia: Justice in the Baltic". Time. 19 August 1940. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Ilmjärv, Magnus (2004). Hääletu alistumine: Eesti, Läti ja Leedu välispoliitilise orientatsiooni kujunemine ja iseseisvuse kaotus. 1920. aastate keskpaigast anneksioonini (in Estonian). Tallinn: Argo. ISBN 9949-415-04-7.

- ↑ "Resolution on the situation in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania". Official Journal of the European Communities. C. European Parliament. 42/78. 13 January 1983.

- ↑ "Linda Soomre Memorial Plaque". British Embassy in Tallinn. 30 May 2005. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008.

- ↑ McHugh, James Frank; Pacy, James S. (2001). Diplomats without a country: Baltic diplomacy, international law, and the Cold War. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31878-6.

- ↑ Lande, David A. (2000). Resistance! Occupied Europe and Its Defiance of Hitler. Osceola, WI: MBI. p. 200. ISBN 0-7603-0745-8.

- ↑ Smith, Graham (1996). The Baltic States: The national self-determination of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-312-16192-1.

- 1 2 "The Virtual Jewish History Tour: Estonia". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Miller-Korpi, Katy (May 1998). "The Holocaust in the Baltics". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Estonian International Commission for Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity". Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Vaivara". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "Holocaust Markers, Estonia". United States Commission for the Preservation of America's Heritage Abroad. 19 February 2009. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ Hiio, Toomas. "The Red Army invasion of Estonia in 1944". Estonica Encyclopedia About Estonia. Eesti Instituut. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ↑ ERR (20 July 2015). "35 years since Tallinn Olympic regatta". ERR. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ "History of Tallinn". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ↑ "A short overview of the Russian history". Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ↑ Pollack, Detlef; Jan Wielgohs (2004). Dissent and Opposition in Communist Eastern Europe. Ashgate Publishing. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-7546-3790-5.

- ↑ Kamm, Henry (25 August 1991). "Soviet turmoil; Yeltsin, Repaying a Favor, Formally Recognizes Estonian and Latvian Independence". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ↑ Devroy, Ann (3 September 1991). "Bush, after delay, grants Baltic states formal recognition". The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ↑ A. Rüütel, Eesti riiklikust iseseisvusest Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine ("Estonian National Independence"), Eesti Vabariigi Ülemnõukogu Otsus (Estonian Supreme Council decision) 20 August 1991, Riigi Teataja. Accessed 8 June 2013.

- ↑ World Development Indicators

- ↑ "В Эстонии пенсия по старости за 19 лет выросла в 15 раз :: Балтийский курс | новости и аналитика". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ↑ Kümme aastat uut Eestit, 1993 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Eesti Päevaleht, 14. juuli 2001.

- ↑ "Sweden pays tribute". www.thelocal.se.

- ↑ Henley, Jon; correspondent, Jon Henley Europe (23 January 2023). "Estonia ferry disaster inquiry backs finding bow door was to blame". The Guardian.

- 1 2 "Deadlock in Estonia election". BBC News Online. 3 March 2003. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ↑ "Center-left party wins popular vote in Estonia". TheStar.com. 3 March 2003. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ↑ "Election leaves hung parliament". The Independent. 3 March 2003. p. 9.