| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 700,000 (1970) Today 50 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Larger diaspora in India, Germany, United States, United Kingdom, and Canada[1] | |

| Religions | |

| Hinduism[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Pashto, Hindko, Punjabi, Dari, Sindhi, and Hindustani (Urdu-Hindi) |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Religion in Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| Majority |

| Sunni Islam |

| Minority |

| Historic/Extinct |

| Controversy |

Hinduism in Afghanistan is practiced by a tiny minority of Afghans, about 30-40 individuals as of 2021,[3][4][5] who live mostly in the cities of Kabul and Jalalabad. Afghan Hindus are ethnically Pashtun,[6] Hindkowan (Hindki), Punjabi, or Sindhi and primarily speak Pashto, Hindko, Punjabi, Sindhi, Dari, and Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu).

Before the Islamic conquest of Afghanistan, the Afghan people were multi-religious.[7] Religious persecution, discrimination, and forced conversion of Hindus in Afghanistan perpetrated by Muslims, has caused the Afghan Hindus, along with Buddhist and Sikh population, to dwindle from Afghanistan, and mostly to India.[8]

Background

Apart from the Hindkowans, the Indo-Aryan native inhabitants of the region, including Pashayi and Nuristanis, were also known to be followers of a sect of Ancient Hinduism, mixed with tribal cultural identities.[9][10][11][12][13] Pashtuns, the majority ethnic group in Afghanistan (officially, no ethnic census ever made), have a component of Vedic ancestors from the Pakthas.[14][15]

"The Pakthas, Bhalanases, Vishanins, Alinas, and Sivas were the five frontier tribes. The Pakthas lived in the hills from which the Kruma originates. Zimmer locates them in present-day eastern Afghanistan, identifying them with the modern Pakthun."[16]

Gandhara, a region encompassing the South-east of Afghanistan, was also a center of Hinduism since the time of the Vedic Period (c. 1500 – c. 1200 BCE),[17][18] along with Buddhism.[19] Later forms of Hinduism were also prevalent in this south-eastern region of the country during the Turk shahis, with Khair Khaneh, a Brahmanical temple being excavated in Kabul and a statue of Gardez Ganesha being found in Paktia province.[20] Most of the remains, including marble statuettes, date to the 7th–8th century, during the time of the Turk Shahi.[21][22][23] The statue of Ganesha from Gardez is now attributed to the period of Turk Shahis in the 7-8th century CE, rather than to their successors the Hindu Shahis (9th-10th century) as has also been suggested.[24] The dating is essentially based on stylistic analysis, as the statue displays great iconographical and stylistic similarities with the works of the Buddhist monastery of Fondukistan, which is also dated to the same period.[24]Hinduism further flourished under the rule of Hindu Shahis, but went into sharp decline with the advent of Islam through the Ghaznavids, who defeated the Shahis. Nonetheless, it continued as a significant minority in Afghanistan until the 21st century, when its number of followers fell to a few hundred.[25][26][27]

History

| Hinduism by country |

|---|

|

| Full list |

.png.webp)

%252C_Jammu_and_Kashmir_or_Afghanistan%252C_Shahi_Period%252C_9th_century_-_Royal_Ontario_Museum_-_DSC09652.JPG.webp)

Prehistory and ancient period (3300–550 BCE)

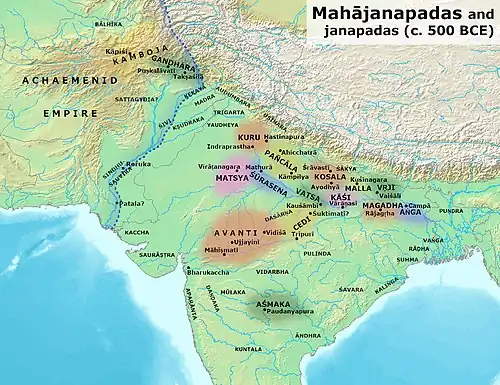

By roughly 2000–1500 BCE, Indo-Aryan inhabitants of the region (mainly in the eastern parts of present-day Afghanistan) were adherents of Hinduism. Notable among these were the Gandharis and Kambojas.[9] The Pashayi and Nuristanis are present day examples of these Indo-Aryan Vedic people.[29][30][31][32][33]

Persian, Greek, and Mauryan periods (550–150 BCE)

Most historians maintain that Afghanistan was inhabited by ancient Arians followed by the Achaemenid before the arrival of Alexander the Great and his Greek army in 330 BC. It became part of the Seleucid Empire after the departure of Alexander three years later. In 305 BCE, the Seleucid Empire lost control of the territory south of the Hindu Kush to the Indian Emperor "Sandrocottus" as a result of the Seleucid-Mauryan War.

Alexander took these away from the Arians and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.[34]

— Strabo, 64 BCE–24 CE

Classical period (150 BCE–650 CE)

When the Chinese travelers Faxian, Song Yun, and Xuanzang explored Afghanistan between the 5th and 7th centuries CE, they wrote numerous travelogues in which reliable information on Afghanistan was stored. They stated that Buddhism was practiced in different parts between the Amu Darya (Oxus River) in the north and the Indus River.[35] However, they did not mention much about Hinduism although Song Yun did state that the Hephthalite rulers did not recognize Buddhism but "preached pseudo gods and killed animals for their meat".[35]

Turk & Kabul Shahi, Zunbil dynasty (650–850 CE)

Before the Islamic conquest of Afghanistan, the territory was a religious sediment of Zoroastrianism, Zunbils, Hinduism and Buddhism. It was inhabited by various peoples, including Persians, Khalaj, Turks, and Pashtuns. Parts of the territory South of Hindu kush were ruled by the Zunbils, offspring of the southern-Hephthalite. The eastern parts (Kabulistan) were controlled by the Turk Shahis.

The Zunbil and Kabul Shahis were connected with the Indian subcontinent through common Buddhism and Zun religions. The Zunbil kings worshipped a sun god by the name of Zun, from which they derived their name. André Wink writes that "the cult of Zun was primarily Hindu, not Buddhist or Zoroastrian"; nonetheless he still mentions them having parallels with Tibetan Buddhism and Zoroastrianism in their rituals.[36][37]

The Kabul Shahi ruled north of the Zunbil territory, which included Kabulistan and Gandahara. The Arabs reached Kabul in 653–654 CE when Abdur Rahman bin Samara, along with 6,000 Arab Muslims, penetrated the Zunbil territory and made their way to the shrine of Zun in Zamindawar, which was believed to be located about five kilometres (three miles) south of Musa Qala in today's Helmand Province of Afghanistan. The General of the Arab army "broke of a hand of the idol and plucked out the rubies which were its eyes in order to persuade the Marzbān of Sīstān of the god's worthlessness."[38]

Though the early Arab invaders spread the message of Islam, they were not able to rule for long. Hence, many contemporary ethnic groups in Afghanistan, including the Pashtuns, Kalash, Pashayi, Nuristanis and Hindkowans continued to practice Hinduism, Buddhism, and Zoroastrianism. The Kabul Shahis decided to build a giant wall around the city to prevent more Arab invasions, and this wall is still visible today.[39]

Hindu Shahi (850–1000 CE)

Willem Vogelsang in his 2002 book writes: "During the 8th and 9th centuries AD the eastern terroritries of modern Afghanistan were still in the hands of non-Muslim rulers. The Muslims tended to regard them as Indians (Hindus), although many of the local rulers and people were apparently of Hunnic or Turkic descent. Yet, the Muslims were right in so far as the non-Muslim population of eastern Afghanistan was, culturally linked to the Indian sub-continent. Most of them were either Hindus or Buddhists. "[40]

In 870 AD the Saffarids from medieval Zaranj, located at the Nad-e Ali site of modern-day Iran (not to be confused with the similarly named modern city of Zaranj in Afghanistan),[41] conquered most of Afghanistan, establishing Muslim governors throughout the land. It is reported that Muslims and non-Muslims still lived side by side before the arrival of the Ghaznavids in the 10th century.

"Kábul has a castle celebrated for its strength, accessible only by one road. In it there are Musulmáns, and it has a town, in which are infidels from Hind."[42]

— Istahkrí, 921 AD

The first confirmed mention of a Hindu in Afghanistan appears in the 982 AD Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam, where it speaks of a king in "Ninhar" (Nangarhar), who shows a public display of conversion to Islam, even though he had over 30 wives, which are described as "Muslim, Afghan, and Hindu" wives.[43] These names were often used as geographical terms. For example, Hindu (or Hindustani) has been historically used as a geographical term to describe someone who was native from the region known as Hindustan (Indian subcontinent), and Afghan as someone who was native from a region called Afghanistan.[44]

Decline (1000–1800 CE)

When Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni began crossing the Indus River into Hindustan (land of Hindus) in the 10th century, the Ghaznavid Muslims began bringing Hindu slaves to what is now Afghanistan. Martin Ewans in his 2002 book writes:

Even then a Hindu dynasty the Hindu Shahis, held Gandhara and the eastern borders. From the tenth century onwards as Persian language and culture continued to spread into Afghanistan, the focus of power shifted to Ghazni, where a Turkic dynasty, who started by ruling the town for the Samanid dynasty of Bokhara, proceeded to create an empire in their own right. The greatest of the Ghaznavids was Mahmud who ruled between 998 and 1030. He expelled the Hindus from Ghandhara, made no fewer than 17 raids into India. He encouraged mass conversions to Islam, in Pakistan as well as in Afghanistan."[46]

Al-Idirisi testifies that until as late as the 12th century, a contract of investiture for every Shahi king was performed at Kabul and that here he was obliged to agree to certain ancient conditions which completed the contract.[47] The Ghaznavid military incursions assured the domination of Sunni Islam in what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan. Various historical sources such as Martin Ewans, E.J. Brill and Farishta have recorded the introduction of Islam to Kabul and other parts of Afghanistan to the conquests of and Mahmud:

The Arabs advanced through Sistan and conquered Sindh early in the eighth century. Elsewhere however their incursions were no more than temporary, and it was not until the rise of the Saffarid dynasty in the ninth century that the frontiers of Islam effectively reached Ghazni and Kabul. Even then a Hindu dynasty the Hindushahis, held Gandhara and eastern borders. From the tenth century onwards as Persian language and culture continued to spread into Afghanistan, the focus of power shifted to Ghazni, where a Turkish dynasty, who started by ruling the town for the Samanid dynasty of Bokhara, proceeded to create an empire in their own right. The greatest of the Ghaznavids was Muhmad who ruled between 998 and 1030. He expelled the Hindus from Gandhara, made no fewer than seventeen raids into northwestern India and succeeded in conquering territory stretching from the Caspian Sea to Varanasi. Bokhara and Samarkand also came under his rule.[48] He encouraged mass conversions to Islam, of Indians as well as Afghans, looted Hindu temples and carried off immense booty, earning for himself, depending on the viewpoint of the observer, the titles of 'Image-breaker' or 'scourge of India'.[48]

Mahmud used his plundered wealth to finance his armies which included mercenaries. The Indian soldiers, presumably Hindus, who were one of the components of the army with their commander called sipahsalar-i-Hinduwan lived in their quarter of Ghazna practicing their own religion. Indian soldiers under their commander Suvendhray remained loyal to Mahmud. They were also used against a Turkic rebel, with the command given to a Hindu named Tilak according to Baihaki.[49]

In his war on Peshawar and Waihind says al-Utbi, Mahmud acquired 500,000 slaves that included children and girls. Men were sold as slaves to even common merchants. The amount of slaves captured in Nardin plummeted their price and male slaves were even bought by common merchants. After raiding Thanesar, he acquired 200,000 slaves.[50]

The renowned 14th-century Moroccan Muslim scholar Ibn Battuta remarked that the Hindu Kush meant the "slayer of Indians", because slaves brought from India who had to pass through there died in large numbers due to the extreme cold and quantity of snow.[51]

The Ghaznavid Empire was further expanded by the Ghurids. During the Khalji dynasty, there was also free movement between people from India and Afghanistan. It continued this way until the Mughals followed by the Suris and the Durranis.

Modern period

The main ethnic groups in Afghanistan which practice Hinduism today are the Punjabis and Sindhis who are believed to have come along with Sikhs as merchants to Afghanistan in the 19th century.[52] Till the collapse of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, there were several thousand Hindus living in the country but today their number is only about 1,000.[53] Most of the others immigrated to India, the European Union, North America or elsewhere.[4]

Afghan Hindus and Afghan Sikhs often share places of worship. Along with the Sikhs, they are all collectively known as Hindki. Linguistic demographics among the Hindu community are diverse and generally follow regional origins: those hailing from Punjab generally speak Punjabi, Sindhis speak Sindhi, and the northern and southern dialects of Hindko. The local Hindu community in Afghanistan is mostly based in the city of Kabul. The 2002 loya jirga had two seats reserved for Hindus[54] and former President Hamid Karzai's economic advisor, Sham Lal Bhatija was an Afghan Hindu.[55]

During the Taliban 1996 to late 2001 rule, Hindus were forced to wear yellow badges in public to identify themselves as non-Muslims. Hindu women were forced to wear burqas, a measure which was claimed to "protect" them from harassment. This was part of the Taliban's plan to segregate "un-Islamic" and "idolatrous" communities from Islamic ones.[56]

The decree was condemned by the Indian and U.S. governments as a violation of religious freedom. Widespread protests against the Taliban regime broke out in Bhopal, India. In the United States, Abraham Foxman, chairman of the Anti-Defamation League, compared the decree to the practices of Nazi Germany, where Jews were required to wear labels identifying them as such.[57] Several influential lawmakers in the United States wore yellow badges with the inscription "I am a Hindu", on the floor of the Senate during the debate as a demonstration of their solidarity with the Hindu minority in Afghanistan.[58][59][60]

Since the 1990s, many Afghan Hindus have fled the country, seeking asylum in countries such as India, Germany and United States.[61]

In July 2013, the Afghan parliament refused to reserve seats for the minority group as a bill reserving seats for the mentioned was voted against. The bill by the then president Hamid Karzai, had tribal people and "women" as "vulnerable groups" who got reservation, but not religious minorities as per the religious equality article in the constitution.[62]

Notable people

- Atma Ram – Afghan Minister and Author.

- Celina Jaitley – Indian Bollywood actress born to an Indian father, Colonel V. K. Jaitly and an Afghan Hindu mother, Meeta Jaitly, who was also from Kabul and was a nurse in the Indian Army.[63][64][65]

- Annet Mahendru – American actress born in Kabul to an Indian father, Ghanshan "Ken" Mahendru whose family had moved from Delhi to Afghanistan for business and a Russian mother, Olga.[66][67][68]

Diaspora

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 80,000 - 280,000[4][69][70][71] (c. 1980) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| India, Germany, United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Australia | |

| 15,000-16,000[2] | |

| 7,000-10,000[72] | |

| 3,000[73] | |

| 1,600[74] | |

| Languages | |

| Hindko (native), English, Hindi , Punjabi, Pashto (older generation), Dari (older generation) | |

As both populations are frequently merged in historic and contemporary estimations, the population ratio between Afghan Sikhs and Hindus is estimated to be 60:40 according to historian Inderjeet Singh.[lower-alpha 1]

With a wide range of population approximations in the absence of official census data and with much of the community concentrated in the provinces of Kabul, Nangarhar, Ghazni, and Kandahar, the Afghan Hindu population was estimated to be between 80,000 and 280,000 in the 1970s,[4][69][lower-alpha 2][70][71][lower-alpha 3] as per estimates by historian Inderjeet Singh, Ehsan Shayegan with the Porsesh Research and Studies Organisation and Rawail Singh, an Afghan Sikh civil rights activist.

In the time of 1980's after the Afghan civil war 1979 the population of Hindus and Sikh fell at a very fast rate due to Taliban's rise to power and religious persecution and discrimination and they migrated from Afghanistan to other countries,[75] The continue rise of Islamization and Taliban insurgency also contributed in the diaspora.[76] The decline was seen mostly in Pashtuns-dominated areas,due to Pashtunistan and Pashtun nationalism,[77] with the Afghan Hindu population declining to 3,000 by 2009.[69]

As per the 2017 data, more than 99% of Afghan Sikhs and Hindus have left the country in the last 3 decades.[71] Many of Afghan Hindus and Sikhs have been settled in Germany, France, United States, Australia, India, Belgium, the Netherlands and other nations.[4]

The Afghan Hindu population declined to approximately 50 in 2020.[4] Later, following the Fall of Kabul in 2021, the Government of India evacuated many Sikhs and Hindus out of the country due to the Taliban takeover. As a result, only one Hindu priest remains in the nation today, also acting as Temple guard.[78]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 180,000 | — |

| 2005 | 79,521 | −55.8% |

| 2010 | 10,700 | −86.5% |

| 2020 | 50 | −99.5% |

| Source: [lower-alpha 4][79][80][81] | ||

| Year | Percent | Increase |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1.6% | |

| 2005 | 0.35% | -1.25% |

| 2010 | 0.04% | -0.31 |

| 2020 | 0.04% | - |

Ancient Hindu temples

| Place | Description | Other information | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polusha | Bhima Devi (Durga) and temple of Maheshvera | Visited by Xuanzang | [82] |

| Sakawand | Temple dedicated to Surya | [83][84] | |

| Asamai Temple | The Asamai temple is at the foothills of the central Kabul hill Koh-e Asamai | [85] | |

| Bhairo Temple | Shor Bazaar | [86] | |

| Mangaldwar Mandir | [87] |

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to Singh, there were at least 2 lakh Sikhs and Hindus (in a 60:40 ratio) in Afghanistan until the 1970s.[4]

- ↑ “In the 70s, there were around 700,000 Hindus and Sikhs, and now they are estimated to be less than 7,000,” Shayegan says.[69]

- ↑ “An investigation by TOLOnews reveals that the Sikh and Hindu population number was 220,000 in the 1980's.[71]

- ↑ As both populations are frequently merged in historic and contemporary estimations, the population ratio between Afghan Sikhs and Hindus is estimated to be 60:40 according to historian Inderjeet Singh.[4] The 1980 estimate is derived from this population ratio, using the average of the estimated population range of 80,000 to 280,000 from the era, taken from the preceding source, along with the three following sources.[69][70][71]

References

- ↑ Country Policy and Information Note: Afghanistan: Hindus and Sikhs (PDF). Home Office, United Kingdom (Report). 6.0. March 2021. p. 15. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- 1 2 Singh, Manpreet (22 August 2014). "Dark days continue for Sikhs and Hindus in Afghanistan". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "Afghan Sikhs, Hindus meet Taliban officials, are assured of safety". MSN.

Speaking to The Indian Express over the phone from Kabul, Gurnam Singh, president of the Gurdwara Dashmesh Pita Sri Guru Gobind Singh ji Singh Sabha Karte Parwan, said around 300 people — 280 Sikhs and 30-40 Hindus — have taken shelter at the gurdwara since the Taliban started taking over provinces of Afghanistan.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Goyal, Divya (28 July 2020). "Sikhs and Hindus of Afghanistan — how many remain, why they want to leave". The Indian Express.

- ↑ "3.14.3. Hindus and Sikhs". European Union Agency for Asylum. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ↑ Ali, Tariq (2003). The clash of fundamentalisms: crusades, jihads and modernity. Verso. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-85984-457-1. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

The friends from Peshawar would speak of Hindu and Sikh Pashtuns who had migrated to India. In the tribal areas – the no man's land between Afghanistan and Pakistan – quite a few Hindus stayed on and were protected by the tribal codes. The same was true in Afghanistan itself (till the mujahidin and the Taliban arrived).

- ↑ Wink, André (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7Th-11th Centuries. BRILL. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8.

- ↑ Hutter, Manfred (2018). "Afghanistan". In Basu, Helene; Jacobsen, Knut A.; Malinar, Angelika; Narayanan, Vasudha (eds.). Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/2212-5019_BEH_COM_9000000190. ISBN 978-90-04-17641-6. ISSN 2212-5019.

- 1 2 UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Taxila

- ↑ Minahan, James B. (10 February 2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 217. ISBN 9781610690188.

Historically, north and east Afghanistan was considered part of the Indian cultural and religious sphere. Early accounts of the region mention the Pashayi as living in a region producing rice and sugarcane, with many wooded areas. Many of the people of the region were Buddhists, though small groups of Hindus and others with tribal religions were noted.

- ↑ Weekes, Richard V. (1984). Muslim peoples: a world ethnographic survey. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 601. ISBN 9780313233920.

- ↑ Khanam, R. (2005). Encyclopaedic ethnography of Middle-East and Central Asia. Global Vision Publishing House. p. 631. ISBN 9788182200654.

- ↑ "The Pashayi of Afghanistan". Bethany World Prayer Center. 1997. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

Before their conversion to Islam, the Pashayi followed a religion that was probably a corrupt form of Hinduism and Buddhism. Today, they are Sunni (orthodox) Muslims of the Hanafite sect.

- ↑ India: from Indus Valley civilisation to Mauryas By Gyan Swarup Gupta Published by Concept Publishing Company, 1999 ISBN 81-7022-763-1, ISBN 978-81-7022-763-2, page 199.

- ↑ Comrie, Bernard (1990). The World's Major Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 549.

- ↑ Ancient Pakistan: Volume 3, University of Peshawar. Dept. of Archaeology - 1967, Page 23

- ↑ "Rigveda 1.126:7, English translation by Ralph TH Griffith".

- ↑ Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1997). A History of Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-81-208-0095-3.

- ↑

- Schmidt, Karl J. (1995). An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History, p.120: "In addition to being a center of religion for Buddhists, as well as Hindus, Taxila was a thriving center for art, culture, and learning."

- Srinivasan, Doris Meth (2008). "Hindu Deities in Gandharan art," in Gandhara, The Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan: Legends, Monasteries, and Paradise, pp.130-143: "Gandhara was not cut off from the heartland of early Hinduism in the Gangetic Valley. The two regions shared cultural and political connections and trade relations and this facilitated the adoption and exchange of religious ideas. [...] It is during the Kushan Era that flowering of religious imagery occurred. [...] Gandhara often introduced its own idiosyncratic expression upon the Buddhist and Hindu imagery it had initially come in contact with."

- Blurton, T. Richard (1993). Hindu Art, Harvard University Press: "The earliest figures of Shiva which show him in purely human form come from the area of ancient Gandhara" (p.84) and "Coins from Gandhara of the first century BC show Lakshmi [...] four-armed, on a lotus." (p.176)

- ↑ Kuwayama, Shoshin (1976). "The Turki Śāhis and Relevant Brahmanical Sculptures in Afghanistan". East and West. 26 (3/4): 407. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29756318.

- ↑ KUWAYAMA (Kyoto City University of Fine Arts), SHOSHIN (1975). "KHAIR KHANEH AND ITS CHINESE EVIDENCES". Orient. XI.

- ↑ Kuwayama, Shoshin (1976). "The Turki Śāhis and Relevant Brahmanical Sculptures in Afghanistan" (PDF). East and West. 26 (3/4): 375–407. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29756318.

- ↑ Hackin, Joseph (1936). Recherches Archéologiques au Col de Khair khaneh près de Kābul : vol.1 / Page 77 (Grayscale High Resolution Image). DAFA.

- 1 2 "It is not therefore possible to attribute these pieces to the Hindu Shahi period. They should be attributed to the Shahi period before the Hindu Shahis originated by the Brahman wazir Kallar, that is, the Turki Shahis." p.405 " According to the above sources, Brahmanism and Buddhism are properly supposed to have coexisted especially during the 7th-8th century A.D. just before the Muslim hegemony. The marble sculptures from eastern Afghanistan should not be attributed to the period of the Hindu Shahis but to that of the Turki Shahis." p.407 in Kuwayama, Shoshin (1976). "The Turki Śāhis and Relevant Brahmanical Sculptures in Afghanistan". East and West. 26 (3/4): 375–407. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29756318.

- ↑ "Contained within a clay urn were a gold bracteate with the portrait of a ruler, three early drachms of the Turk-Shahis (Type 236, one of which is countermarked), and a countermarked drachm of the Sasanian king Khusro II dating from year 37 of his reign (= 626/7). The two countermarks on Khusro 's drachm prove that the urn could only have been deposited after 689" ALRAM, MICHAEL (2014). "From the Sasanians to the Huns New Numismatic Evidence from the Hindu Kush" (PDF). The Numismatic Chronicle. 174: 282–285. ISSN 0078-2696. JSTOR 44710198.

- ↑ Kim, Hyun Jin (19 November 2015). The Huns. Routledge. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-1-317-34091-1.

- ↑ Alram, Michael; Filigenzi, Anna; Kinberger, Michaela; Nell, Daniel; Pfisterer, Matthias; Vondrovec, Klaus. "The Countenance of the other (The Coins of the Huns and Western Turks in Central Asia and India) 2012-2013 exhibit: 16. THE HINDU SHAHIS IN KABULISTAN AND GANDHARA AND THE ARAB CONQUEST". Pro.geo.univie.ac.at. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ↑ For photograph of statue and details of inscription, see: Dhavalikar, M. K., "Gaņeśa: Myth and Reality", in: Brown 1991, pp. 50, 63.

- ↑ Minahan, James B. (10 February 2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 217. ISBN 9781610690188.

Historically, north and east Afghanistan was considered part of the Indian cultural and religious sphere. Early accounts of the region mention the Pashayi as living in a region producing rice and sugarcane, with many wooded areas. Many of the people of the region were Buddhists, though small groups of Hindus and others with tribal religions were noted.

- ↑ Weekes, Richard V. (1984). Muslim peoples: a world ethnographic survey. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 601. ISBN 9780313233920.

- ↑ Khanam, R. (2005). Encyclopaedic ethnography of Middle-East and Central Asia. Global Vision Publishing House. p. 631. ISBN 9788182200654.

- ↑ "The Pashayi of Afghanistan". Bethany World Prayer Center. 1997. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

Before their conversion to Islam, the Pashayi followed a religion that was probably a corrupt form of Hinduism and Buddhism. Today, they are Sunni (orthodox) Muslims of the Hanafite sect.

- ↑ Richard F. Strand (31 December 2005). "Richard Strand's Nuristân Site: Peoples and Languages of Nuristan". nuristan.info. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ↑ Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād (1972). "An Historical Guide to Kabul – The Name". American International School of Kabul. Archived from the original on 30 August 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- 1 2 "Chinese Travelers in Afghanistan". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. 1969. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ André Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Brill 1990. p 118

- ↑ "Parallels have been noted with pre-Buddhist religious and monarchy practices in Tibet and had Zoroastrianism in its ritual". Al- Hind: The slave kings and the Islamic conquest. 2, page 118. By André Wink

- ↑ André Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Brill 1990. p 120

- ↑ "The Kabul Times Annual". Kabul Times Pub. Agency, Information, Culture Ministry., 1970. p. 220.

- ↑ by Willem Vogelsang, Edition: illustrated Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 2002 Page 188

- ↑ Mehrafarin, Reza; Haji, Seyyed Rasool Mousavi (2010). "In Search of Ram Shahrestan The Capital of the Sistan Province in the Sassanid Era". Central Asiatic Journal. 54 (2): 256–272. ISSN 0008-9192. JSTOR 41928560.

- ↑ "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul (p.3)". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ↑ Vogelsang, Willem (2002). The Afghans. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 18. ISBN 0-631-19841-5. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ↑ David Lorenzen (2006). Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History. Yoda Press. p. 9. ISBN 9788190227261.

- ↑ Hutchinson's story of the nations, containing the Egyptians, the Chinese, India, the Babylonian nation, the Hittites, the Assyrians, the Phoenicians and the Carthaginians, the Phrygians, the Lydians, and other nations of Asia Minor. London, Hutchinson. p. 150.

- ↑ Afghanistan: A New History, by Martin Ewans Edition: 2, illustrated Published by Routledge, 2002 Page 15 ISBN 0-415-29826-1, ISBN 978-0-415-29826-1

- ↑ Al-Idrisi, p. 67, Maqbul Ahmed; Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World, 1991, p. 127, Andre Wink.

- 1 2 Afghanistan: a new history by Martin Ewans Edition: 2, illustrated Published by Routledge, 2002 Page 15 ISBN 0-415-29826-1, ISBN 978-0-415-29826-1. "He encouraged mass conversions to Islam, of Indians as well as Afghans, looted Hindu temples and carried off immense booty, earning for himself, depending on the viewpoint of the observer, the titles of 'Image-breaker' or 'Scourge of India'."

- ↑ Romila Thapar (2005). Somanatha: The Many Voices of a History. Verso. p. 40. ISBN 9781844670208.

- ↑ Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest : 11Th-13th Centuries by Andre Wink, Published by BRILL, 1990 Page 126 ISBN 9-004-10236-1, ISBN 978-9-004-10236-1.

- ↑ Christoph Witzenrath (2016). Eurasian Slavery, Ransom and Abolition in World History, 1200-1860. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-317-14002-3.

Ibn Battuta, the renowned Moroccan fourteenth century world traveller remarked in a spine-chilling passage that Hindu Kush means slayer of the Indians, because the slave boys and girls who are brought from India die there in large numbers as a result of the extreme cold and the quantity of snow.

- ↑ Majumder, Sanjoy (25 September 2003). "Sikhs struggle in Afghanistan". BBC. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ↑ Cross, Tony (14 November 2009). "Sikhs struggle for recognition in the Islamic republic". Radio France Internationale www1.rfi.fr. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ Afghanistan's loya jirga BBC 0- June 7, 2002

- ↑ "Karzai's Hindu Afghan serves his country". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ Taliban to mark Afghan Hindus Archived 2007-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, CNN

- ↑ Taliban: Hindus Must Wear Identity Labels, People's Daily

- ↑ "U.S. House condemns Taliban over Hindu badges – WWRN – World-wide Religious News". Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "rediff.com US edition: US lawmakers say 'We are Hindus'". Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ "Afghanistan News Center". Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ↑ Immigrant Hinduism in Germany: Tamils from Sri Lanka and Their Temples, pluralism.org

- ↑ "We condemn the discrimination against Sikhs and Hindus of Afghanistan". Kabul Press. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ "'Accident...' will show another side of me: Celina". The Indian Express. 26 December 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

Jaitley, born in Kabul

- ↑ "India in vogue, Vogue in India". Telegraphindia.com. 9 September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "History Beckons Celina". The Times of India. 8 November 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

I was born in Kabul

- ↑ de Croisset, Phoebe (16 December 2016). "Multiple Identities". SBJCT Journal. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

I am an Indian-Russian-Afghan-American

- ↑ "Annet Mahendru Talk Dead to Me Interview". Talk Dead To Me Skybound. 8 December 2020. Event occurs at 05:46. YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

My dad was an Afghan Hindu

- ↑ Masih, Archana (27 January 2015). "Nina! The 'spy' with designs on India". Rediff.com. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ruchi Kumar (1 January 2017). "The decline of Afghanistan's Hindu and Sikh communities". Al Jazeera.

- 1 2 3 Ruchi Kumar (19 October 2017). "Afghan Hindus and Sikhs celebrate Diwali without 'pomp and splendour' amid fear". Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nearly 99% Of Hindus, Sikhs Left Afghanistan in Last Three decades". TOLOnews. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "Mitgliederzahlen: Hinduismus – REMID – Religionswissenschaftlicher Medien- und Informationsdienst e.V."

- ↑ "Afghans in New York Metro Area". Unreached New York.

- ↑ "Edward Snowden: the whistleblower behind the NSA surveillance revelations | US news". The Guardian. 9 June 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ↑ KABIR, NAHID A. (2005). "The Economic Plight of the Afghans in Australia, 1860—2000". Islamic Studies. 44 (2): 229–250. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20838963.

- ↑ Service, Tribune News. "Facing Islamic State, last embattled Sikhs, Hindus leave Afghanistan". Tribuneindia News Service. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "Hindus in Afghanistan Archives". Hindu Council of Australia. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ "Last Hindu priest refuses to abandon Afghanistan ancestral temple, says 'will consider it Seva even if Taliban kills me'". Zee News. 17 August 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ↑ "Country Profile: Afghanistan (Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan)". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ↑ "Religious Composition by Country, 2010-2050". pewresearch. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ↑ "Nearly 99% Of Hindus, Sikhs Left Afghanistan in Last Three decades". tolonews.com. 25 June 2016.

- ↑ Dutt, R. C. (1995). The Civilization of India. Asian Educational Services. pp. 107–109. ISBN 978-81-206-1108-5.

- ↑ Gupta, Parmanand (1977). Geographical Names in Ancient Indian Inscriptions. Concept Publishing Company. p. 53.

- ↑ The Journal of the Bihar Research Society, Volumes 47-49. Bihar and Orissa Research Society. 1961. p. 83.

- ↑ "The lost Sun Temple of Multan in Pakistan". Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ↑ Hindu Castes and Sects, by Jogendra Nath Bhattacharya, Published by Editors Indian, Calcutta, 1968- page 470.

- ↑ Tate 1911, p. 198.

Sources

- Brown, Robert (1991), Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God, Albany: State University of New York, ISBN 978-0791406571

- Hutter, Manfred (2018). "Afghanistan". In Basu, Helene; Jacobsen, Knut A.; Malinar, Angelika; Narayanan, Vasudha (eds.). Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/2212-5019_BEH_COM_9000000190. ISBN 978-90-04-17641-6. ISSN 2212-5019.

- Dhavalikar, M. K. (1991). "Gaņeśa: Myth and Reality". In Brown, Robert L. (ed.). Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God. SUNY Series in Tantric Studies. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. pp. 49–68. ISBN 978-0-7914-0656-4. OCLC 42855045.

- Tate, George Passman (1911). The Kingdom of Afghanistan. Asian Education Services. pp. 201–224. ISBN 9-788-120-61586-1.

- "Inscription throws new light to Hindu rule in Afghanistan". Indian Express. 5 January 2000. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006.