| History of Stuttgart |

|---|

|

| Duchy of Swabia (950-1250) |

| County of Württemberg (1251–1495) |

| Duchy of Württemberg (1496–1806) |

| Electorate of Württemberg (1803–1806) |

| Kingdom of Württemberg (1806-1918) |

| German Empire (1871–1918) |

| Free People's State of Württemberg (1918–45) |

| Weimar Republic (1919-33) |

| Nazi Germany (1933–45) |

| Bombing of Stuttgart in World War II |

| West Germany (1945–90) |

| Federal Republic of Germany (1990-present) |

| See also |

The history of Stuttgart traces its origins in the mid 10th century. However, the history of the land upon which Stuttgart stands has a far longer history dating back several thousands years to prehistoric peoples who sought the fertile soil of the Neckar river valley.

Prehistoric time

Prehistoric finds made in the area of Zuffenhausen and around the region at the Lemberg in the Swabian Jura and Burgholzhof, Stammheim, and the Viesenhäuser Hof inside the city date back to the Paleolithic.[1] Evidence of settlements of Neolithic peoples all the way up to the Alemanni tribes also exists.

Excavations and findings dated to the Paleolithic period suggest the usage of the hills of the Neckar valley near Stuttgart as rest stops as far back as 300,000 years ago (Middle Paleolithic). Further corroboration is found with the discovery of tools and processed bones discovered in the travertine quarries of Bad Cannstatt.[2]

Antiquity

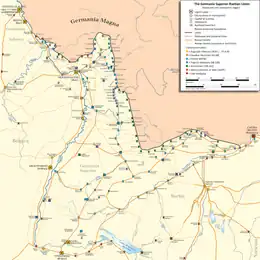

Bad Cannstatt's name originates from a Castra stativa, Cannstatt Castrum, the massive Roman Castra that was erected on the hilly ridge in AD 90 to protect the valuable river crossing and local trade.[3][4]

Roman Cannstatt was one of the largest Roman cities in today's Baden-Württemberg after Lopodunum (Ladenburg) and Sumelocenna (Rottenburg am Neckar). In Roman times, almost all intercity traffic from Mogontiacum (Mainz) and Rhineland to Augusta Vindelicorum (Augsburg) and Raetia passed today's Bad Cannstatt. Various mineral springs of Bad Cannstatt appear to have already been used by the Romans as well.[5]

Kingdom of Württemberg and the German Empire

Industry

In 1845, the first gasworks in the city began operation, providing gas lighting. The plant was located on the Seidenstrasse, near the Hoppenlaufriedhof, and came into being after a demonstration at the royal court that so impressed King William I of Württemberg that he requested gas lighting in all of his buildings. At 6 PM, 19 February 1865, a house near St. Leonhard's Church was destroyed by the city's first gas explosion, an event that killed four, of whom two were children.[6]

In 1886, Robert Bosch opened his very first workshop in Stuttgart. The automobile and motorcycle were purported to have been invented in Stuttgart (by Karl Benz and subsequently industrialized in 1887 by Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach at the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft), earning the city the moniker "Cradle of the Automobile."[7] After a fire in one of the manufacturing plants in 1903, the company moved to Untertürkheim and adopted the name Daimler AG.

Weimar Republic

On 1 October 1920, Erwin Rommel was commissioned as a captain and assigned command of the 13th Infantry Regiment based in Stuttgart. In his nine years at this post, his regiment was involved in the quelling of civil disturbances across Germany.[8]

Nazi Germany

Allied bombing of Stuttgart

Stuttgart endured 53 air raids over the course of the Allied strategic bombing during World War II, the first of which occurred on 25 August 1940 and destroyed 17 buildings.[9]

Allied occupation

When the French army entered Stuttgart in 1945, they are alleged to have been responsible for the rape of around 3,000 women and eight men.[lower-alpha 1]

Notes

- ↑ Giles MacDonogh states in After the Reich that German estimates numbered around 5,000 women while official figures say that 1,198 women were raped by French soldiers, according to R.F. Keeling's book Gruesome Harvest.[10]

References

- ↑ Gühring, Kull & et al. (2004), p. 41.

- ↑ Müller-Beck (1983), pp. 252, 257–260.

- ↑ "Stuttgart (Germany)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009.

- ↑ "Early history of Stuttgart". en.driveline-online.de. driveLINE.

- ↑ "New facts about the Romans in Bad Cannstatt". archaeologie-online.de (in German). Archäologie Online. 14 November 2008.

- ↑ Stuttgarter Zeitung, 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Stuttgart – Where Business Meets the Future. CD issued by Stuttgart Town Hall, Department for Economic Development, 2005.

- ↑ Butler (2015), pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Page on the air attacks against Stuttgart. Archived March 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- ↑ MacDonogh (2009), p. 79.

Sources

English

- Butler, Daniel Allen (2015). Field Marshal: The Life and Death of Erwin Rommel. Casemate. ISBN 978-1-61200-297-2.

- Hoffmeister, Gerhart; Tubach, Frederic C. From the Nazi Era to German Unification. Germany: 2000 Years. Vol. III. New York City, NY: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-0601-7.

- MacDonogh, Giles (2009). After the Reich: The Brutal History of the Allied Occupation. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00338-9.

German

- Gühring, Albrecht; Beer, Mathias; Binder, Petra; Ehmer, Hermann; Friederich, Susanne; Glück, Manfred; Heinz, Reinhard; Juréwitz, Peter; Kull, Ulrich; Meyle, Wolfgang; Müller, Roland; Raberg, Frank; Rees, Werner; W., Hermann (2004). Zuffenhausen. Dorf – Stadt – Stadtbezirk. Zuffenhausen: Verein zur Förderung der Heimat- und Partnerschaftspflege sowie der Jugend- und Altenhilfe. ISBN 3-00-013395-X.

- Müller-Beck, Hansjürgen (1983). Urgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag. ISBN 3-8062-0217-6.

News references

- Stuttgarter Zeitung

- Faltin, Thomas (31 January 2015). "Gasexplosion erschütterte die ganze Stadt". Stuttgarter Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 3 July 2018.