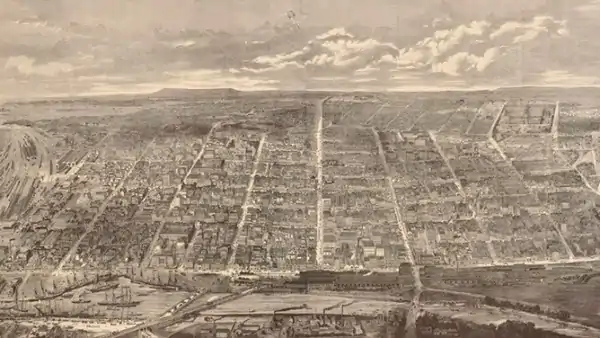

Hoddle Grid is the contemporary name given to the approximately 1-by-0.5-mile (1.61 km × 0.80 km) grid of streets that form the Melbourne central business district, Australia. Bounded by Flinders Street, Spring Street, La Trobe Street, and Spencer Street, it lies at an angle to the rest of the Melbourne suburban grid, and so is easily recognisable. It is named after the surveyor Robert Hoddle, who marked it out in 1837 (to Lonsdale Street, extended to La Trobe Street the next year), establishing the first formal town plan. This grid of streets, laid out when there were only a few hundred settlers, became the nucleus for what is now Melbourne, a city of over five million people.

History

The grid of streets that is now central Melbourne was laid out by surveyor Robert Hoddle when he arrived in early 1837 with New South Wales Governor Bourke in order to regularise the fledgling unauthorised settlement.[1] The unusual dimensions of the allotments and the incorporation of narrow 'little' streets were the result of compromise between Hoddle's desire to employ the regulations established in 1829 by previous NSW Governor Ralph Darling, requiring square blocks and wide streets, and Bourke's desire for rear access ways (now the 'little' streets).[2]

The placement of the grid was determined firstly by the fact that the fledgling settlement was already established at that point on the Yarra River, next to a natural shipping basin, just below a rocky outcrop known as 'the falls', above which the water was usually fresh. It was placed to run roughly parallel to the course of the river, with its western half closest to the basin, and spanned the mostly gently undulating area between the small hills of Batman's Hill to the west, and Eastern Hill.[3] Elizabeth Street, Melbourne in the centre of the grid coincided with the lowest point and roughly paralleled an existing gully.

The streets were surveyed 1 1/2 chains (a chain being 66ft, so they were 99ft; 30m), the blocks at 10 chains (660 ft; 200 m) square, with allotments 1 chain (66 ft; 20 m) wide, as per Darling's Regulations[4]). However, at Governor Bourke's insistence, 'little streets' were inserted east west through the middle of the blocks to allow for rear access to the long, narrow allotments. These were to be 1 chain (66 ft; 20 m), but Bourke's suggestion of keeping the allotments the standard size by making the main streets narrower was resisted by Hoddle, leaving them as surveyed, so they became 1/2 chain (33ft; 10m), taken out of the depth of the blocks either side, the end result making the allotments smaller than usual. As per the Darling regulations, the area around the grid was reserved for future expansion and government purposes, and some blocks and allotments were held back from sale and were allocated for government use, a market and a church.[5] The first land sale, of allotments around a block reserved as the site for the Customs House, took place in the settlement on 1 June 1837.

The lack of a public square or formal open space within the grid was criticised as early as 1850, and it has been claimed that Governor Bourke specifically discouraged the inclusion of such spaces “to deter a ‘spirit of democracy’ from breaking out”.[6] However there is little evidence that Bourke had a view on the matter, and the Darling regulations made no mention of including a central square (as either desirable or not). Instead, simple grid plans, with lots or blocks set aside for public buildings and sometimes a park, were standard practice across Australia in government settlements, to facilitate the creation of regular allotments for sale. Notable exceptions include the five central squares of the privately developed plan of Adelaide (also 1839), and the axially placed, though not central, church square set aside in the 1829 plan for Perth. Most of today's well known public squares, such as King George Square in Brisbane, Martin Place in Sydney, and Melbourne's City Square, were created in the 20th century, by widening streets and demolishing buildings.

Robert Hoddle remained the surveyor for the district until 1853, and laid out all the surrounding subdivisions in a north south, east west grid, excepting the area between La Trobe Street and Victoria Street, which is sometimes included in the 'Hoddle Grid', and is usually officially included in the CBD.

This has meant that the original grid sits at a marked angle to the rest of the city, and is easily recognised on any map. Most inhabitants of Melbourne know all the streets of the Hoddle Grid by name, and the order they occur.

The whole town was at first accommodated within the Hoddle Grid, but the huge surge in immigration brought about by the Victorian gold rush in the 1850s quickly outgrew the grid, spreading into the first suburbs in Fitzroy, South Melbourne (Emerald Hill), and beyond.

The Hoddle Grid and its fringes remained the centre and most active part of the city into the mid 20th century, with retail in the centre, fine hotels, banking and prime office space on Collins Street, medical professionals on the Collins Street hill, legal professions around William Street, and warehousing along Flinders Lane and in the western end. Government buildings like GPO, State Library, Supreme Court, and Customs House occupied various blocks, while Parliament House and a government precinct developed on the east side of Spring Street. The swampy area to the south soon hosted rail lines, with many suburban trains converging on Flinders Street railway station near Princes Bridge, the gateway to the city from the south, and Spencer Street station on the western edge was the terminus for country trains, as well as more suburban lines. Up until 1930s, the river bank west of Queen Street River was lined with wharfs for cargo and passenger ships.

Residential uses, most notably the slums of Little Lonsdale Street, were largely replaced by commercial uses by the 1950s, with residential not making a return until the 1990s with the conversion of older buildings. Since the 2000s this has accelerated with numerous high rise apartment buildings and student housing projects. The CBD still retains a central role for retail, with flagship department stores, specialist shops, and luxury brands, and the upper floors of older buildings and down the city's famous laneways host a busy nightlife of numerous bars and restaurants, and a street art culture.

Use of the phrase

The term 'Hoddle Grid' emerged in common use only in the 21st century. While it has long been well known that Robert Hoddle laid out the central grid of streets most commonly referred to as 'the City', it was not traditionally named after him. In the 19th and early 20th Century the focus was more on Collins Street, the grandest thoroughfare, with the most expensive and exclusive buildings along its length, while the western and northern edges comprised unremarkable low rise residential and light industrial development.

By the 1950s the phrase 'Golden Mile' comes into use, describing Collins Street itself.[7][8]

The "Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme Report", published by the Board of Works in 1954 refers to the area as 'The Central Business Area'.[9]

The phrase 'CBD' or Central Business District appears in the 1960s, probably within the publication of the 'Borrie Report' in 1964, and the subsequent Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme, enacted in 1968.[10] CBD is still the most common phrase to refer to the central grid area of Melbourne.

Official planning strategies in the 1980s and 90s did not use the phrase 'Hoddle Grid'; for instance the State Government's "Central Melbourne : Framework for the Future", published December 1984, identifies it as 'the formal city grid' (p25), while the City of Melbourne's 'Grids and Greenery', published 1987, picks out the skewed grid of streets in various graphics, but only names it as 'the city centre'.

More recently the Encyclopedia of Melbourne, published in book form in 2005, and online in 2008, calls it the "City Grid', while another entry on Roads, describing the wider subdivision of Melbourne, calls the central area 'the Hoddle grid'.[11]

The phrase appeared in The Age newspaper as early as 2002.[12]

Specifications

All major streets are one and a half chains (99 ft; 30 m) in width, while all blocks are exactly 10 chains (660 ft; 200 m) square. The total dimensions, including widths of streets, are thus 93.5 chains (6,170 ft; 1,880 m) by 47.5 chains (3,140 ft; 960 m). The grid's longest axis is oriented 70 degrees clockwise from true north, to align better with the course of the Yarra River. The majority of Melbourne is oriented at 8 degrees clockwise from true north - noting that magnetic north was 8.05° E in 1900, increasing to 11.7° E in 2009.[13]

East-west streets

Parallel to the Yarra River:

- Flinders Street (southernmost)

- Flinders Lane1

- Collins Street

- Little Collins Street2

- Bourke Street, incorporating Bourke Street Mall

- Little Bourke Street3

- Lonsdale Street

- Little Lonsdale Street4

- La Trobe Street (frequently incorrectly written as Latrobe or LaTrobe) (northernmost)

1 One-way westbound, except two-way between Market and Spencer Streets

2 One-way westbound, except two-way between King and Spencer Streets

3 One-way westbound

4 One-way eastbound

North-south streets

Perpendicular to the Yarra River:

- Spencer Street (westernmost)

- King Street

- William Street

- Queen Street

- Elizabeth Street

- Swanston Street

- Russell Street

- Exhibition Street

- Spring Street (easternmost)

The Mile Grid

Robert Hoddle also surveyed a separate north-south grid of streets at one mile spacing around the central city grid. The origin of this grid, marked on the 1837 map, was on the crest of Batman's Hill, striking magnetic north for one mile, to an east west line (now Victoria Street/Parade) marking the northern extent of the government reserve outside the central grid. The rest of metropolitan Melbourne generally follows this grid pattern.

See also

References

- ↑ "Grid Plan". eMelbourne. School of Historical & Philosophical Studies, The University of Melbourne. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ↑ Lewis, Miles (1995). Melbourne: The City's History and Development. Melbourne: City of Melbourne. pp. 25–29.

- ↑ Lewis, Miles (1995). Melbourne: The City's History and Development. Melbourne: City of Melbourne. pp. 25–29.

- ↑ Freestone, Robert (2010). Urban Nation: Australia's Planning Heritage. Csiro Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 9780643096981. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ↑ Lewis, Miles (1995). Melbourne:The City's History and Development. City of Melbourne. pp. 25–31.

- ↑ Annear, Robyn (2005). A City Lost and Found - Whelan the Wrecker's Melbourne. Black Inc. p. 214. ISBN 9781863956505.

- ↑ "Green Heart Plan in City". The Argus. 7 February 1956. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ↑ "City has Glamour after Dark". The Argus. 19 February 1954. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ↑ "Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme 1954: Report". Policy and Strategy - Planning for Melbourne. DELWP. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ↑ Borrie, E.F. (1964). Report on a planning scheme for the central business area of the City of Melbourne. Melbourne: Melbourne City Council.

- ↑ Lay, M.G. "Roads". Encyclopaedia of Melbourne. School of Historical & Philosophical Studies, The University of Melbourne. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ↑ Millar, Royce (6 July 2002). "The well-heeled, sterile city blues". The Age. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ↑ Magnetic Declination