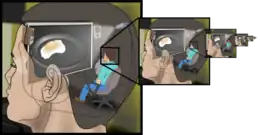

The homunculus argument is an informal fallacy whereby a concept is explained in terms of the concept itself, recursively, without first defining or explaining the original concept.[1] This fallacy arises most commonly in the theory of vision. One may explain human vision by noting that light from the outside world forms an image on the retinas in the eyes and something (or someone) in the brain looks at these images as if they are images on a movie screen (this theory of vision is sometimes termed the theory of the Cartesian theater: it is most associated, nowadays, with the psychologist David Marr). The question arises as to the nature of this internal viewer. The assumption here is that there is a "little man" or "homunculus" inside the brain "looking at" the movie.

The reason why this is a fallacy may be understood by asking how the homunculus "sees" the internal movie. The answer is that there is another homunculus inside the first homunculus's "head" or "brain" looking at this "movie". But that raises the question of how this homunculus sees the "outside world". To answer that seems to require positing another homunculus inside this second homunculus's head, and so forth. In other words, a situation of infinite regress is created. The problem with the homunculus argument is that it tries to account for a phenomenon in terms of the very phenomenon that it is supposed to explain.[2]

In terms of rules

Another example is with cognitivist theories that argue that the human brain uses "rules" to carry out operations (these rules often conceptualised as being like the algorithms of a computer program). For example, in his work of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, Noam Chomsky argued that (in the words of one of his books) human beings use Rules and Representations (or to be more specific, rules acting on representations) in order to cognate (more recently Chomsky has abandoned this view; cf. the Minimalist Program).

Now, in terms of (say) chess, the players are given "rules" (i.e., the rules of chess) to follow. So: who uses these rules? The answer is self-evident: the players of the game (of chess) use the rules: it's not the case that the rules themselves play chess. The rules themselves are merely inert marks on paper until a human being reads, understands and uses them. But what about the "rules" that are, allegedly, inside our head (brain)? Who reads, understands and uses them? Again, the implicit answer is, and some would argue must be, a "homunculus": a little man who reads the rules of the world and then gives orders to the body to act on them. But again we are in a situation of infinite regress, because this implies that the homunculus utilizes cognitive processes that are also rule bound, which presupposes another homunculus inside its head, and so on and so forth. Therefore, so the argument goes, theories of mind that imply or state explicitly that cognition is rule bound cannot be correct unless some way is found to "ground" the regress.

This is important because it is often assumed in cognitive science that rules and algorithms are essentially the same: in other words, the theory that cognition is rule bound is often believed to imply that thought (cognition) is essentially the manipulation of algorithms, and this is one of the key assumptions of some varieties of artificial intelligence.

Homunculus arguments are always fallacious unless some way can be found to "ground" the regress. In psychology and philosophy of mind, "homunculus arguments" (or the "homunculus fallacies") are extremely useful for detecting where theories of mind fail or are incomplete.

The homunculus fallacy is closely related to Ryle's regress.

See also

References

- ↑ Kenny, Anthony (1971). "The Homunculus Fallacy". In Grene, Marjorie (ed.). Interpretations of Life and Mind: Essays around the problem of reduction. New York: Humanities Press. pp. 65–74. ISBN 978-0-391-00144-2.

- ↑ Richard L. Gregory. (1987), The Oxford Companion to the Mind, Oxford University Press