Horses and horse culture play a large role in the daily and national life in Mongolia. It is traditionally said that "A Mongol without a horse is like a bird without the wings." Elizabeth Kimball Kendall, who travelled through Mongolia in 1911, observed, "To appreciate the Mongol you must see him on horseback,—and indeed you rarely see him otherwise, for he does not put foot to ground if he can help it. The Mongol without his pony is only half a Mongol, but with his pony he is as good as two men. It is a fine sight to see him tearing over the plain, loose bridle, easy seat, much like the Western cowboy, but with less sprawl." (see also A Wayfarer in China).

Mongolia holds more than 3 million horses, an equine population which outnumbers the country's human population. The horses live outdoors all year at 30 °C (86 °F) in summer down to −40 °C (−40 °F) in winter, and search for food on their own. The mare's milk is processed into the national beverage airag, and some animals are slaughtered for meat. Other than that, they serve as riding animals, both for the daily work of the nomads and in horse racing. Mongol horses were a key factor during the 13th century conquest of the Mongol Empire.

Of the five kinds of herd animals typically recognized in Mongolia (horses, camels, oxen/yaks, sheep and goats), horses are seen to have the highest prestige.[1] A nomad with many horses is considered wealthy. Mongol people individually have favorite horses. Each family member has his or her own horse, and some family members favor their preferred horses by letting them out of hard jobs.

Horses are generally considered the province of men, although women also have extensive knowledge of horsemanship. Men do the herding, racing and make the tack. Traditionally, men[2] (or in modern times, women) also milk the mares.[3]

Care and grooming

Compared to Western methods, Mongolians take a very "hands off" approach to horse care. Horses are not bathed or fed special foods like grain or hay. Rather, they are simply allowed to graze freely on the steppe, digging through the snow to find forage in the winter. Because nature provides so well for the Mongol horse, they cost little to nothing to raise. As such, horses are not an expensive luxury item as in Western culture, but a practical necessity of everyday life. Herdsmen regard their horses as both a form of wealth and a source of the daily necessities: transportation, food and drink. Mongol riders have individual favorite horses. Each family member has his or her own horse, which may receive special treatment.

In Mongolia, barns, pastures and stables are the exception, not the rule. Horses are generally allowed to roam free; if they are needed, they may be tied up temporarily. The hitching post used for this purpose differs from the usual Western conception of a bar placed across two posts. Such creations are wood intensive, and on the steppe trees are rare. Instead, the horses may be tied to a single wooden pole or a large boulder. Because the horses are allowed to live much the same as wild horses, they require little in the way of hoof care. The hooves are left untrimmed and unshod and farriers are basically nonexistent. Despite the lack of attention, Mongol horses have hard, strong hooves and seldom experience foot problems. During the summer, Mongolian horses will often stand in a river, if available, in order to keep insects off.[4]

Mongolians say that fat horses have "grass in their belly" while lean horses have "water in their belly." Herdsman prefer to make long journeys during seasons when horses are well fed so as to spare tired or thin animals from exertion.[5] Particularly in the spring, horses are vulnerable to exhaustion: "By the end of winter, the animals are a dreadful sight. … The horses are too frail to be ridden and some can barely walk. … When the new grass appears, however, native Mongolian breeds of animals tend to recover very quickly."[6] Horses, along with sheep and goats, have a better chance of surviving difficult winter conditions than cattle and sheep because they are able to separate snow from grass with their dextrous lips. When a zud hits, the typical pattern is for cattle to die first, then sheep, horses, and lastly goats. Thus, horses are the second most winter-resilient animals raised by Mongolians.[7]

Mares begin foaling in May and continue throughout the summer.[6] Sick or cold foals will sometimes be taken into the ger, wrapped in skins or felts, and placed next to fire.[6]

A typical Mongolian herd consists of 15 - 50 mares and geldings under one stallion. Some stallions are allowed to manage herds of up to 70 animals, though these are considered exceptional individuals. The stallion is tasked with leading the herd, siring foals, and defending the herd against wolves. The herd stallion, rather than the human owner, is entrusted with the day to day management of the herd. Elizabeth Kendall observed in 1911 that, "Each drove of horses is in the charge of a stallion which looks sharply after the mares, fighting savagely with any other stallion which attempts to join the herd. I am told that the owner only needs to count his stallions to be sure that all the mares have come home." (see also A Wayfarer in China)

Since the mares are used for foals and milking, they are not often used for work; this is the job of the geldings. Geldings rather than stallions are the preferred work animals. Members of the Darkhad ethnic group ride their stallions only once a year, on three special days during the winter.[3] There are special horses within each herd used for roping, racing, beauty, or distance riding. A herdsman may own one or several herds of horses, each headed by its own stallion.[3] A newly wedded couple will be given a gift of horses by the parents on both the husband and wife's sides. Each family will give the couple 10 - 15 horses apiece and two stallions so that they can start up their own herd. The extra stallion is sold or traded away.

Mane trimming varies by region. Stallions are always left untrimmed; a long, thick mane is considered a sign of strength. Geldings, however, are clipped. Among the Darkhad ethnic group, the forelock is cut short and the bridle path is left unclipped. Sometimes the mane of a horse will be clipped short except for one patch near the withers. Mongolians save the cut off mane of the horse for spiritual reasons. Both tail and mane hair can also be made into various spiritual and utilitarian products, i.e. spirit banners or rope. Manes are always left long in the winter to keep the horse warm. The sole grooming tool used is a brush. The tail is generally left unclipped. When a horse is gelded in the spring, the very tip of the tail may be cut off. Branding may or may not be done; if it is, it is done in the fall.[3]

During races, the forelock is put in a topknot that stands up from the horse's head. The hairy part of the tail may also have a tie placed around it midway down.[8] For race horses, the owner will also have a wooden sweat scraper to clean off the horse after a race. After the Naadam, spectators will come up to touch the winning horses' mane and sweat as both a sign of respect and a way to imbibe good fortune.[8] The winning horse is also sprinkled with airag.[9]

Gelding is done when a colt is 2 – 3 years old. The date chosen for the event may be set by a lama so as to ensure good fortune. The colts to be castrated are caught and their legs are tied. The animals are then pushed on their side. The horse's topmost hindleg is tied to its neck, exposing its testicles. The genitals are washed, then cut off with a knife that has been cleaned in boiling water. Afterwards, the wound is rinsed with mare's milk, a practice intended to encourage healing. An observer reported, "The animal does not appear to experience much pain during the operation, but tends to be in a state of confusion when let loose on the steppe."[10] An entire family will typically join in the castration process; depending on the number of colts to be castrated, several households may participate so that the castration may be completed in one day.

When the work of castration is completed, the testicles are used for ritual purposes. One of the amputated testicles is punctured with a knife so as to permit the insertion of a rope; the rope is then fastened to the new gelding's tail with the assumption that once the testicle has dried, the wound will have finished healing. The remaining testicle is cooked in the hearth ashes and eaten by the head of the household to acquire the strength of the stallion.[11]

_(16769576222).jpg.webp)

Riding and training

Mongolian nomads have long been considered to be some of the best horsemen in the world. During the time of Genghis Khan, Mongol horse archers were capable of feats such as sliding down the side of their horse to shield their body from enemy arrows, while simultaneously holding their bow under the horse's chin and returning fire, all at full gallop. In 1934, Haslund described how a herdsman breaking in a semi-wild horse was able to ungirth and unsaddle his horse as it bucked underneath him. He wrote, "It is a pleasure to see the Mongols in association with their horses, and to see them on horseback is a joy. ...[T]he strength, swiftness and elegance of a Mongol surpass that of any ballet dancer."[12] This same skill in horsemanship held true in antiquity. Giovanni de Carpini, a Franciscan friar who visited Mongolia during the 1240s, observed that "their children begin as soon as they are two or three years old to ride and manage horses and to gallop on them, and they are given bows to suit their stature and are taught to shoot; they are extremely agile and also intrepid. Young girls and women ride and gallop on horseback with agility like men."[13] Today as in the Middle Ages, the education of a modern Mongolian horseman begins in childhood. Parents will place their child on a horse and hold them there before the child can even hang on without assistance. By the age of 4, children are riding horses with their parents.[14] By age 6, children can ride in races;[8] by age 10, they are learning to make their own tack.

Carpini noted that the Mongols did not use spurs (these were unknown in Central Asia at that time); they did, however use a short whip. This whip had a leather loop at the end; when the rider was not using it, he would let it hang from his wrist so that he could have his hands free to perform tasks, e.g. archery.[15] It was taboo to use the whip as a prop or to touch an arrow to the whip; such crimes were punishable by death. It was also punishable by death to strike a horse with a bridle.[2] Haslund noted that as of 1934, it was considered a crime to strike a horse with a whip in areas in front of the stirrup.[16]

Mongolian cultural norms encourage the humane treatment of horses. After spending years in the country, Haslund could not recall even one instance of seeing a horse mistreated. Indeed, he found that Mongols who had been to China and observed their use of horses typically came back "filled with righteous wrath and indignation over the heavy loads and cruel treatment that human beings there deal out to their animals."[17] In Genghis Khan's time, there were strict rules dictating the way horses were to be used on campaign. The Khan instructed his general Subutai, "See to it that your men keep their crupper hanging loose on their mounts and the bit of their bridle out of the mouth, except when you allow them to hunt. That way they won't be able to gallop off at their whim [tiring out the horses unnecessarily]. Having established these rules--see to it you seize and beat any man who breaks them. ... Any man...who ignores this decree, cut off his head where he stands."[18]

Mongolian tack differs from Western tack in being made almost completely of raw hide[19] and using knots[20] instead of metal connectors. Tack design follows a "one size fits all" approach, with saddles, halters and bits all produced in a single size. Mongolian tack is very light compared to western tack; hobbles in particular are about half the weight of their Western counterparts.[19] The Mongol pack saddle can be adjusted to fit yaks and bactrian camels.[19]

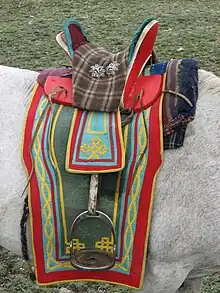

The modern Mongolian riding saddle is very tall, with a wooden frame and several decorated metal disks that stand out from the sides. It has a high pommel and cantle, and is placed upon a felt saddlecloth to protect the horse's back. The horse's thick coat also provides a barrier that helps prevent saddle sores. In the Middle Ages, the Mongols used a different style of saddle, the chief difference being that the cantle flattened out in the rear rather than rising to a peak like the cantle of a modern Mongolian saddle. This allowed the rider greater freedom of movement; with a minimal saddle, a mounted archer could more readily swivel his torso to shoot arrows towards the rear.[15]

The Mongolian saddle, both medieval and modern, has short stirrups rather like those used by modern race horses.[15] The design of the stirrups makes it possible for the rider to control the horse with his legs, leaving his hands free for tasks like archery or holding a catch-pole.[15] Riders will frequently stand in the stirrups while riding.[2]

The design of the Mongolian saddle allows only marginal control of the gait. In most situations, the horse will decide the gait on its own, while the rider is occupied with other tasks such as herding cattle. Very often, a Mongol horse will choose to canter. The occasional Mongol horse will have an ambling gait, which is to say that it will lift both its left hooves at one time, then both its right hooves at one time, etc. Such horses are called joroo, and is said that they "glide as if though on ice, so smoothly that one can trot along on one holding a full cup and not spill any of the contents."[2] The Mongols, who ride hundreds of kilometres on horseback across the roadless steppe, place a very high value on horses with a smooth gait.[3]

Mongolian horsemen are required to learn everything necessary to care for a horse. This is because they do not typically employ outside experts such as trainers, farriers or veterinarians and must do everything themselves. For particularly difficult problems, the local elders may be called in or even an outside vet if one can be found. Materials such as books on horse training or medical care are uncommon and seldom used. Informally knowledge is passed down orally from parent to child.

Though Mongolian horses are small, they are used to carry quite large, heavy riders. This ability is due in part to the riders' habit of frequently switching off horses so as not to overtax any particular animal. However, Mongol horses are also very strong. A Darkhad horse weighing only 250 kg. can carry a load of 300 kg—the equivalent of carrying another horse on its back. When pulling a cart, a team of four Mongol horses can draw a load of 4400 lbs for 50–60 km a day.[21]

Horses are usually not ridden until they are three years old; a two-year-old horse may be broken with a particularly light rider so as to avoid back problems. The breaking process is quite simple: the rider simply gets on and lets the horse run until it is exhausted. Then the horse is taught to respond to the pull of the reins. In Khövsgöl Province, the horses may be worked in round pens. This practice is not common in the rest of Mongolia however; wood is too scarce to be wasted on fencing.[3]

Since individual horses are ridden relatively infrequently, they become nearly wild and must be caught and broken anew each time they are used. A herdsman must first catch the horse he wants; to do this, he mounts a special catch-horse which has been trained for the purpose. Carrying an urga, a lasso attached to a long pole, he chases after the horse he wants and loops the urga around its neck. The catch-horse helps the herdsmen pull back on the looped horse until it grows tired and stops running. At this point another rider will come up and put a saddle on it and mount. The horse will run and buck until it recalls its earlier training and allows itself to be ridden.[12] The catching part may take up to several hours, depending on the terrain, the catcher's skill, and the equipment used.[4]

As warhorses

Mongol horses are best known for their role as the war steeds of Genghis Khan, who is reputed to have said: "It is easy to conquer the world from the back of a horse." The Mongol soldier relied on his horses to provide him with food, drink, transportation, armor, shoes, ornamentation, bowstring, rope, fire, sport, music, hunting, entertainment, spiritual power, and in case of his death, a mount to ride in the afterlife. The Khan's army, weapons, war tack and military tactics were built around the idea of mounted cavalry archers, and to a lesser extent light and heavy cavalry. In the Secret History of the Mongols, Genghis Khan is recorded as urging his general Subutai to pursue his enemies as though they were wild horses with a catch-pole loop around their neck.[22] Captured enemy rulers were sometimes trampled to death by horses.[23]

As a war vehicle, the Mongol horse compared favorably with other breeds in use at the time. Mongol horses needed little water[19] and did not need to be fed daily rations of grain, as many European breeds did. Their ability to forage beneath the snow and find their own fodder allowed the Mongols freedom to operate without long supply trains, a factor which was key to their military success. Mongol horses were bred to survive in harsh conditions, making it possible for the Mongols to mount successful winter campaigns against Russia. The excellent long distance endurance of the Mongol horse allowed warriors to outlast enemy cavalry during battle; the same endurance granted the Mongols a communications advantage across their widely spread out fronts, since messages had to be conveyed by horse. The main disadvantage of the Mongol horse as a war steed was that it was slower than some of the other breeds it faced on the battlefield. However, this drawback was compensated for by the fact that it was typically required to carry less weight than other cavalry horses. Although the Mongol horse is almost a pony, it acquired a fearsome reputation among the Mongols' enemies. Matthew Paris, an English writer in the 1200s, described the small steeds as, "big, strong horses, which eat branches and even trees, and which they [the Mongols] have to mount by the help of three steps on account of the shortness of their thighs." (Though short, the Mongols did not actually use steps to mount.)[24]

It is said that a Mongol warrior's horse would come at his whistle and follow him around, doglike. Each warrior would bring a small herd of horses with him (3 - 5 being average, but up to 20) as remounts. They would alternate horses so that they always rode a fresh horse.[25] Giovanni de Carpini noted that after a Mongol warrior had ridden a particular horse, the man would not ride it again for three or four days.[26]

Soldiers preferred to ride lactating mares because they could use them as milk animals. In times of desperation, they would also slit a minor vein in their horse's neck and drain some blood into a cup. This they would drink either "plain" or mixed with milk or water.[25] This habit of blood-drinking (which applied to camels as well as horses) shocked the Mongols' enemies. Matthew Paris, an English writer in the 1200s, wrote scornfully, "...they [the Mongols] have misused their captives as they have their mares. For they are inhuman and beastly, rather monsters than men, thirsting for and drinking blood..."[24]

The Mongol armies did not have long supply trains; instead, they and their horses lived off the land and the people who dwelt there. Ibn al-Athir observed, "Moreover they [the Mongols] need no commissariat, nor the conveyance of supplies, for they have with them sheep, cows, horses, and the like quadrupeds, the flesh of which they eat, naught else. As for their beasts which they ride, these dig into the earth with their hoofs and eat the roots of plants, knowing naught of barley. And so, when they alight anywhere, they have need of nothing from without."[27] It was important for the Mongols to find good grazing for their herds of remounts, or failing that, to capture enemy foodstuff. During the conquest of the city of Bukhara, Genghis Khan's cry, "Feed the horses!" indicated that soldiers were to pillage and slaughter the inhabitants.[23] Genghis Khan warned Subutai to be careful to conserve his horses' strength on long campaigns, warning that it would do no good to spare them after they were already used up.[22]

Mongolian horses have long been used for hunting, which was viewed as both a sport, a means of livelihood, and as training for military ventures. Animals like gazelles were taken with bow and arrow from the backs of horses, while other game was rounded up by mounted riders.[28] To the Mongols, the tactics used in hunting game from horseback were little different from those used in hunting enemy cavalry on horseback. Armies would also hunt for food while on the march, an activity which could wear out the horses. Genghis Khan, concerned that his soldiers would use up the strength of their horses before reaching the battlefield, instructed general Subutai that he should set limits on the amount of hunting his men did.[29] As of 1911, horsemen still hunted wolves from horseback. Elizabeth Kendall observed, "These Mongolian wolves are big and savage, often attacking the herds, and one alone will pull down a good horse or steer. The people wage more or less unsuccessful war upon them and at times they organize a sort of battue. Men, armed with lassoes, are stationed at strategic points, while others, routing the wolves from their lair, drive them within reach." (see also A Wayfarer in China).

The Mongols used many tools meant specifically to attack mounted riders. The spear used by warriors had a hook at the end which was used for dehorsing opponents and snagging the legs of enemies' horses. They also used whistling arrows to frighten opposing horses. Mongols had no qualms about shooting the mounts out from under other cavalrymen; there was even a particular type of arrow especially designed for the purpose.[30] For this reason, horses of well-to-do individuals were armored with iron or hardened leather plates called lamellae.[30] The armor was a full body covering with five distinct pieces that shielded the head, neck, body and hindquarters. The Mongols preferred to use a whip to urge their horses on during battle, while their European opponents preferred spurs. The whip provided them with a tactical advantage because it was more safe and effective than spurs: a whip can be felt through armor and does not harm the horse, whereas spurs cannot be felt through armor and injure the horse.[30] When the Mongols wished to conceal their movements or make themselves appear more numerous, they would sometimes tie a tree branch to their horse's tail to raise dust, obscuring their position and creating the illusion of a larger group of horsemen.[31]

A story goes that the future general Jebe shot the horse out from under Genghis Khan during a battle. The animal in question had had a white-speckled muzzle. When Jebe was captured later, he admitted flat out to the Khan's face that he had fired the arrow in question. Genghis Khan admired the man's courage, and instead of killing Jebe, he took him into his own army. Many years later, when Jebe had become a general, Genghis Khan became concerned that his subordinate had ambitions to replace him. To allay the Khan's suspicions, Jebe sent him a gift of 1,000 horses with white speckled muzzles.[2]

Horses were used to guide the Mongols' makeshift boats across rivers. Pian de Carpine described the procedure as follows: "When they come to a river, they cross it in the following way, even if it is a large one: the chiefs have a round, light skin, around the top of which they have loopholes very close together through which they pass a cord, and they stretch it so that it bellies out, and this they fill with clothes and other things, and then they bind it down very tightly. After that they put their saddles and other hard things on it, and the men likewise sit on it. Then they tie the boat thus made to the tail of a horse, and a man swims along ahead leading it; or they sometimes have two oars, and with them they row across the water, thus crossing the river. Some of the poorer people have a leather pouch, well sewn, each man having one; and in this pouch or sack they put their clothing and all their things, and they tie the mouth of the bag tightly, and tie it to the tail of a horse, then they cross as stated above."[24]

The Mongols covered continental distances on horseback. In particular, general Subutai's European army was fighting a full 5,000 km distant from their homeland in Mongolia. Since his forces did not travel on a direct beeline but made various diversions en route, the 5,000 kilometers actually translates to a horseback ride that has been estimated at 8,000 km in total length.[32]

Messages were carried rapidly throughout the Mongol empire by a pony-express style relay system in which riders would pass messages from station to station, switching to a fresh horse each time. A similar system of horse-expedited mail was still practiced in Mongolia as of 1911. Elizabeth Kendall described it as follows: "Under the treaties of 1858 and 1860 a post-route between the Russian frontier and Kalgan was established, and in spite of the competing railway through Manchuria, a horse-post still crosses the desert three times a month each way. The Mongols who are employed for the work go through from city to city in seven days, galloping all the way, with frequent changes of horses and, less frequent, of men."

Spiritual beliefs

It is believed that the spirit of a stallion resides within his mane; thus, a long, thick mane is considered a mark of a strong animal. The mane of a stallion is never cut, though the manes of geldings are. After a stallion dies, the owner may save the mane. The first foal of the year will also have a blue scarf tied around its neck; this foal is believed to represent the strength of the year's crop of foals. When a Mongol rider passes an ovoo, they may offer some of their horse's tail hairs before proceeding.[8]

A family may have a sacred horse among their herd, which is signified by a blue scarf tied around the neck. The horse is generally never ridden, though on rare occasions the head of the household may do so. Historically, horses were sacrificed on special occasions; it is recorded that 40 horses were sacrificed at the funeral of Genghis Khan.[33] When a Mongol warrior died, his horse would be killed and buried with him.[34] In 1253, William of Rubruk observed the scene of a recent funeral where the skins of sixteen horses had been hung up on long poles, with four skins pointing towards each corner of the compass. There was also kumis (mare's milk) for the deceased to drink.[35]

Mare's milk was used in a variety of religious ceremonies. In "The Secret History of the Mongols," it is recorded that Genghis Khan sprinkled mare's milk on the ground as a way to honor a mountain for protecting him. Before battle, the Mongols would sprinkle mare's milk on the ground to ensure victory. Sprinkled milk was also used for purification; envoys to the Khan were required to pass between two fires while being sprinkled with mare's milk to cleanse them of evil devices and witchcraft. William of Rubruck noted in 1253 that, "If he [a Mongol master of the house] were to drink [liquor while] seated on a horse, he first before he drinks pours a little on the neck or the mane of the horse."[35]

In modern times, Mongol horses may be blessed with a sprinkling of mare's milk before a race.[36] After the national Naadam races, the winning horses are sprinkled with mare's milk, and the top five horses in each racing category are named the "airag's five." [37] After a Naadam wrestling match, the winner will take a sip of airag and toss some into the air. Milk may also be sprinkled after people who are leaving on a journey.[38]

When a favorite horse dies, the owner may dispose of the remains in several ways. To show respect, they may take the horse's skull and place it on an oovo, a pile of rocks used in the shamanic religion. Others believe that when a horse is killed for food, its skull should be left in the field because of the sanctity of the horse. It is considered disrespectful for a horse's skull or hooves to be stepped upon; for this reason, such remains may be hung from a tree.

Horses are believed to have spirits that can help or hurt their owner after death. When a deceased horse's spirit is content, the owner's herd will flourish; if not, then the herd will fail.

Horses in myth, song, and folklore

Mythology

According to shamanic tradition, a person's soul is called a wind horse (хийморь, Khiimori). The wind horse is depicted on the official Mongolian coat of arms, which features a winged horse. Among the shamanistic tngri, the 99 highest divinities of Tengerism, there is an equestrian deity called Kisaγa Tngri who protects souls (and also riches). Another divinity, Ataγa Tngri, is a protector of horses themselves.[39] The drum used by shamans was often made of horse skin, the drum itself standing for "the saddle animal on which the shaman rides or the mount that carries the invoked spirit to the shaman."[40]

In the Gesar epic, the demons ride unnatural horses that have no tails.[41]

Folklore and song

Like many cultures, the Mongols have tales of magical horses. In one story, a Mongolian Robin Hood figure stole livestock from the rich and gave them to the poor. One day he was being pursued by lawmen on horseback, and he came to a river his horse could not cross. It looked like he would soon be caught, but seeing a mountain in the distance, he prayed to it for help and his horse rose from the ground and flew over the river to the top of the mountain.[42]

In Mongolia, the horse is "omnipresent in song, in stories, and in art."[3] One legend revolves around the invention of the horsehead fiddle, a favorite Mongolian instrument. In this tale, a shepherd named Namjil the Cuckoo received the gift of a flying horse; he would mount it at night and fly to meet his beloved. A jealous woman had the horse’s wings cut off, so that the horse fell from the air and died. The grieving shepherd made a horsehead fiddle from the now-wingless horse's skin and tail hair, and used it to play poignant songs about his horse.[43]

Another legend about the origin of the horsehead fiddle claims that it was invented by a boy named Sükhe (or Suho). After a wicked lord slew the boy's prized white horse, the horse's spirit came to Sükhe in a dream and instructed him to make an instrument from the horse's body, so the two could still be together and neither would be lonely. So the first horsehead fiddle was assembled, with horse bones as its neck, horsehair strings, horse skin covering its wooden soundbox, and its scroll carved into the shape of a horse head.

Horses are common characters in Mongolian folklore. The frequently recurring motif of the young foal who becomes separated from his family and must make his way in the world alone is a type of story that has been described as endemic to Mongolian culture.[44] The horse also figures prominently in song. In 1934, Haslund wrote, "Of forty-two Mongolian songs which I noted down in my years in Mongolia no less than seventeen are about horses. They have titles like: 'The little black with velvet back,' 'The dun with lively ears,' and they are all full of touching evidences of the Mongol's love for his horses."[45]

Given the deep integration of horses into Mongolian culture, the Mongols have a large vocabulary of equine terminology. There are over 500 words in the Mongolian language describing the traits of horses, with 250 terms for coat color/pattern alone.[46] In Mongolian literature, this rich vocabulary leads to constructions that seem wordy in English, i.e. a Mongol poet may say, "He rode a 3 year old dun mare with a black stripe down its back" rather than "he rode a horse."

Epic poems

Mongolian epic poems always assign a special horse to the hero. The horse may be born at the same time as the hero or just before him. It possesses great strength, speed, magic, and intelligence. The horse may have the power to magically change its shape; it provides the hero with counsel, and can even predict the future. As regards the latter ability, one plot development that occurs repeatedly is the disaster that results when the hero disregards his horse's advice. In other epics the hero cannot defeat his monstrous manggus foe without asking for help from his horse. The horse may even use its magical powers to assist the hero in courting his beloved. "From the frequency of the horse motif in this tradition, one could easily get the impression that horses are as important as their masters. We have not yet found any epic in this nomadic tradition that is without a steed and the assistance it provides."[47]

In the Jangar epic

One of the three traditional Mongolian oral epics is the Jangar, in which horses play roles almost as important as those of the heroes. The most famous horse from the epic is Aranjagaan, Jangar's mount. Aranjagaan was sired by a seven-year-old Heavenly Horse who came down to mate with a mortal mare by a lake. (There is intertextual conflict about this later in the epic, where Aranjagaan's father is described as an ordinary horse who was ridden by Jangar's father.) Aranjagaan's capabilities are described in epic style: "He was red all over and had a body the size of a hill. He had a huge tail and ears. He had hooves the size of a sheep pen and a butt as hard as cast iron. As soon as he was born, he hissed and frightened away wolves, which had stalked near the stall. At the age of one, he joined a war. At two, he fought wars north and south. He was in his prime at the age of seven. Aranjagaan hissed excitedly, making tree leaves, grasses and stones thunder and even frightening boars dozens of baraa away. His power seemed to radiate from within him. One leap forward would bring his rider hundreds of meters away. His power would hold anyone in great awe. His red brilliance was fiery and dazzled everyone who saw him. ... Even Aranjagaan's roaring shook enemies and weakened their knees."[48] Nor are these epic descriptions limited to Aranjagaan. Even the nameless horses like Altan Gheej's crimson mount have poetically glorified capabilities. The crimson horse is described as having a tail 80 feet long and ears like pestles. It can run at a full gallop for two months straight and swim across a sea for 25 days. Moligen Tabuga's scarlet horse is described as being as large as forty-nine seas. Sanale's red horse has ears like iron bars. These sizes and abilities are typical for all epic steeds in the Jangar. In particular, the size of the tail, ears, and hooves are praised, though occasionally one will find the horse's legs described as tree trunks, etc.[48]

It is the horses, not the heroes, that claim divine ancestry. Indeed, the motif of the divinely born horse is repeated in the epic, as when the history of Aletan Kale's wondrous buff and white horse is given: "The horse's father was from heaven. The heavenly horse met and mated with a beautiful female horse at the bank of Kas Lake. Then the heavenly horse licked her face and flew away, leaving a heartbroken companion. The female horse gave birth to the buff and white horse with endless expectations." Horses like the buff and white and Aranjagaan are themselves considered divine on account of their parentage.[48]

In Mongolian epics, horses save their riders in battle and even fight alongside of them. When Jangar is struck with a poisoned arrow, Aranjagaan realizes what has happened and carefully carries Jangar to safety. To keep his swaying master from toppling off, the horse skillfully leans back and forth, even going so far as to crouching down his forelegs or hindlegs when ascending and descending hills to keep his back level. When they arrive at a house, he lays down to let his rider gently fall off. On another occasion, Aranjagaan runs to a place where a battle is occurring and begins to fight, riderless, alongside the hero. During fights, the epic narrative typically switches back and forth between describing the combat of riders and the actions of their horses, i.e. the hero throws a spear, then the hero's horse lunges forward to pursue an enemy. In battles, the poets describe the horse as a self-willed actor. There are few descriptions of rein-pulling or leg guidance; rather, the impression is that the horse chooses how best to carry on the fight as it works in concert with its rider. The horses bite and kick enemies, and will even bite enemy horses. During a battle, Sanale's red horse "provided him with inexhaustible power. It kicked the enemies eighteen thousand times from the left and then eighteen thousand times from the right so that the spears, broadswords, and arrows were broken. It fought like a huge eagle extending its wings."[48] Horses can be wounded. In a long-running battle, Altan Gheej's crimson horse is "beaten black and blue and scabbed all over. With eyes covered by blood, the horse was nearly trapped by the enemy several times. Seeing the situation was urgent, Altan Gheej whipped the horse to the sea and swam for awhile. The blood was cleaned and the wounds healed up magically."[48] The horses are eager for battle. When Hongor's livid horse sees Hongor equipped for war, it kicks and snorts with excitement.

The horses often have adventures of their own, like getting caught in a whirlpool and escaping by grabbing a branch in their teeth and hauling themselves onto shore. The poet does not fail to describe the horse's exhausted collapse on the bank, the rider's concern, and the horse's subsequent recovery as it stands up, joyfully shakes its mane, and begins cropping grass. Mongolian poets consider it important to describe a horse's feelings and actions as well as those of the human characters. For example, when Jangar stops to drink at a cool stream and delights in the beauty of nature, the poet also notes that Aranjagaan grazes and enjoys a roll in the grass. On another pleasant excursion, Aranjagaan's rider begins to sing, and Aranjagaan moves his hooves in time with the song.

Heroes and horses converse with one another on a regular basis. The hero will urge and rebuke his horse, demanding more speed, as when Altan Gheej says to his crimson horse after 50 days and nights of running, "Aren't you known as a 'flying arrow' or a 'blue eagle'? Why haven't you crossed over your enclosure after so many days? If so, when can we arrive at our destination?" or when swimming a sea, "A hero in need is a hero indeed. Where is your mighty power? How can you get adrift like this?"[48] The horses will also tell their riders when they can't give anymore. For example, when Sanale is fleeing a devil, his sweating, exhausted horse says, "My master, I have tried my best and cannot run faster. Please get rid of the devil, or else we will both have trouble." On another occasion, Sanale's red horse neighs loudly to wake his master from a deep, drunken slumber, then rebukes him for sleeping when he should be killing devils. Sanale, ashamed, apologizes to the horse. The red horse replies impassively, "Drinking delays and drinking hard kills."[48]

Heroes in the Jangar show great affection for their horses. They will rub their horse's nose affectionately and care for them in times of hardship. When Sanale was forced to flee into the Gobi desert, he and his horse became exhausted with hunger and thirst. The horse saw a plant that it recognized as poisonous, but couldn't resist eating it. Immediately it collapsed in agony. Weeping, Sanale grasped the horse's neck and told it that he had nothing to give it but his own flesh, but that they must go on or their enemies would kill them. The horse was deeply moved at his master's concern and cried. It heroically managed to rise and bear Sanale away. When the horse later collapses, Sanale tries to help it stand. Eventually, afraid that his pursuers will harm the weakened horse, Sanale hides it in a cave while he fights them off. During an exhausting battle, Sabar's maroon horse gasps, "Master, we have fought for seven days, and I feel dizzy and giddy due to lack of food and water. Can we just rush out and find something to eat?" Sabar leaves the battlefield, finds fodder for his horse, takes a nap while it eats its fill, then returns to the battle and continues fighting.[48]

The epic horses are considered precious possessions, and the quality of a man's horse reveals his status and wealth. When introducing a new hero, the poets inevitably include a description of the hero's prized steed. One of the descriptions of Sanale, for instance, is that "he rides a crimson horse rarely seen on the steppes." Sabar is introduced by describing that he has "an unparalleled sorrel steed worth 100,000 slaves."[48] The horse's fittings are also important. The poet describes Jangar's beautiful clothes, then adds that Aranjagaan was fitted with a golden halter and long silver reins. Because of their value, horses are also important in peace negotiations; for example, Jangar seeks to buy peace from Sanale by offering him the twelve best horses in his herd. The horses, Aranjagaan in particular, are also subject to ransom demands by covetous enemy Khans. On various occasions, hostile Khans demand Aranjagaan as tribute to avoid war. One of the threatened consequences for a defeated enemy is to have all his horses driven off by the victor.

The horses play key roles throughout the story, providing information and assisting the heroes against enemies against enemies. Sanale is almost seduced by a hungry devil disguised as a beautiful temptress, but his horse snorts and blows up her skirt, revealing shaggy legs. Altan Gheej's crimson horse is hitched to the eaves of an enemy Khan's palace and pulls until the entire palace collapses. Sabar's maroon horse magically finds out that Sabar's homeland is being attacked and conveys a message from Jangar to Sabar, asking him to return and save him.

The fact that horses serve as meat animals in Mongolian culture is not ignored in the epic. Sanale warns his red horse that if their enemies catch them, they will eat him and make his equine skin into boots. The heroes carry dry horse meat as provisions as they ride off. During a critical moment in a battle, Hongor says to his horse, "You are my dearest brother, a rare horse. You have never been beaten. If you fail today, I will skin you and eat your meat!"[48] The horse finds fresh strength and fights on. On another occasion, a different hero warns Aranjagaan that the horse will suffer a similar fate if he doesn't arrive in time to help in a critical battle. Aranjagaan replies that he will make it in time, but that if the hero does not win the battle when they arrive, Aranjagaan will buck him off and break his neck.

Catalogue of horses in Jangar

In keeping with the Mongolian tradition of not giving horses names, most of the horses in the Jangar do not have names, but are instead identified by their physical traits. Each horse has a color that sets him apart from the rest.

- Jangar - Aranjagaan, Aranzhale

- Altan Gheej - red horse

- Mengen Shigshirge - Oyomaa, the black horse

- Sanale - crimson/red horse

- Big Belly Guzan Gongbei - black horse "elephant-like"

- Moligen Tabuga - scarlet horse

- Sabar - sorrel horse with white nose, maroon horse

- Hongor - livid horse

- Daughter of Wuchuuhen Tib - yellow horse

- Jaan Taij - yellow leopard horse

- Odon Chagaan - yellow horse

Other

In the Mongolian version of chess, the most powerful piece is the horse.[49]

Products

In Mongolia, horses are a fairly cheap commodity. In 2014, a good Mongol horse could be purchased for $140; a merely decent one for $100, and a race horse for $800 – $1000.[19] In 1934 Henning Haslund reported seeing endless herds that stretched out as far as he could see. One man of his acquaintance owned no less than 14,000 horses.[12]

Mongolian horses are valued for their milk, meat and hair. William of Rubruck described the historical milking process as follows: "They stretch a long rope on the ground fixed to two stakes stuck in the ground, and to this rope they tie toward the third hour the colts of the mares they want to milk. Then the mothers stand near their foal, and allow themselves to be quietly milked; and if one is too wild, then a man takes the colt and brings it to her, allowing it to suck a little; then he takes it away and the milker takes its place."[35] Much the same procedure is still used today. In the summer, mares are milked six times a day, once every two hours. A mare produces an average of 0.11 lbs of milk each time, with a yearly production of 662 lbs total.[21] The milk is used to make the ubiquitous fermented drinks of Mongolia, airag and kumis. One particular variety of "black" kumis, caracosmos, was made entirely from the milk of black mares; this was reserved for the aristocracy.[35] William of Rubruck reported that Batu Khan had the milk of three thousand mares collected and sent to his court on a daily basis.[35] In large herds, the gentlest animals are the preferred milk horses. Milk is also boiled and dried into hard white chunks that can be stored and eaten on journeys. During the communist era, Mongolian factories and mines continued to maintain herds of horses specifically for the purposes of providing airag for their workers, which was considered necessary for health and productivity.[49]

The milking of horses begins midway through July and lasts till late November, sometimes going as long as early December. Of the various animals milked by Mongolians, horses give milk for the second longest period of time (cattle give milk for a longer period). A lama's advice may be sought for the most auspicious date to begin milking. An offering of the first milk may also be made to the spirits at this time.[50] For example, during a spring celebration, a lama may sprinkle the first mare's milk of the year over an ovoo.[51]

Horses are considered meat animals in Mongolia. Each 600 lb. Mongol horse yields about 240 lbs. of meat.[52] The horse in question may be an old, barren, injured or unneeded animal, such as a stallion who has lived past his prime. The meat of horses is considered to be safer to eat than the meat of other livestock. As one Mongolian explained, "Because the horse does not get diseases that other livestock become sick of, [sic] such as tuberculosis and other inflammatory diseases, its meat and milk are considered to be clean." William of Rubruck reported that the Mongols used the intestines of the horses to make sausages. Horses are considered to have the fourth most desirable kind of meat, after sheep, cattle and goats. Mature animals are preferred to young ones, as the taste is considered better. Horses are slaughtered in late November when the animals are at their fattest; it is considered bad practice to slaughter them in the summer.[53]

They would also use the leather from the rear part of the horse's hide to make shoes.[35] Horse skin was one of the materials used for making the bowstring of the Mongols' infamous composite bow. The skin of horses was preferred over that of other animals because it was said to keep its flexibility despite the frigid temperatures of the steppe.[54] Mongol warriors also wore armor made from horse leather soaked in horse urine.[23] The drums used by shamans in rituals were often made of horse hide.[40]

The horse's hair can be used for a number of products. Horsehair ties are part of the traditional Mongolian tent dwelling.[3] The hair can also be used to make rope; it is considered better than leather in wet conditions, because water can be easily shaken out of a horsehair rope but not a leather one. One traditional rope-making technique called for a combination of one third horse hair to two thirds wool.[35]

Tail hair was also used in the creation of musical instruments. The traditional Mongolian horsehead fiddle has two strings made of horse hair. The "male" string is made from 136 tail hairs from a stallion, while the "female" string is made from 105 tail hairs from a mare. The bow is also made of horse hair coated with resin.

Due to the spiritual significance of a horse's mane, black and white mane hair was used to make spirit banners (tugs). Black hair indicated a war tug and white hairs a peace tug. The black hair was taken from bay horses.[2] Warriors wore a peaked helmet with a plume of horsehair on top.[55]

Since there is little wood on the steppe, dry animal dung is gathered as fuel for fire. Bruun notes, "...horse dung especially (and perhaps surprisingly to the uninitiated) gives off a nice fragrance resembling that of incense."[56]

Famous horses

Mongolians do not give their horses names; rather, they identify them by their color, markings, scars, and brands. Perhaps due to the Mongolian habit of not naming their horses, there are few widely known individuals of the breed. One exception to this rule is Arvagarkheer, an 18th century race horse who beat over 1,000 other horses in a race. The city of Arvaikheer was named after him, and he has a painted statue with a blue scarf tied around the neck in Arvaikheer valley.[42]

When U.S Vice President Joe Biden visited Mongolia, he was given a Mongol horse as a gift. He named it "Celtic" and tied two ceremonial knots in the blue silk scarf around the horse's neck. This spooked the horse and it reared, and was led off.[57]

References

- ↑ Cleaves. The Secret History of the Mongols, p. 126

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hoang, Michel. Genghis Khan. New Amsterdam Books, 1991.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Yazdzik, Elisabeth (April 1, 2011). "The Mongolian Horse and Horseman". Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection Paper 1068. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- 1 2 Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe.

- ↑ "The Stallion's Mane - Domestication of the horse". Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- 1 2 3 Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe, p. 53.

- ↑ Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 4 New Atlantis Full Documentaries (2012-04-09). "Mongolia". YouTube. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ↑ Davis, Matthew. When Things Get Dark: A Mongolian Winter's Tale, p. 168.

- ↑ Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe, p. 55.

- ↑ Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe, p. 56.

- 1 2 3 Haslund, Henning. In Secret Mongolia, p. 111.

- ↑ Carpini, quoted in Dawson, C. A Mission to Asia, p. 18.

- ↑ Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe, p. 104.

- 1 2 3 4 Swietoslawski, W. "A confrontation between two worlds: the arms and armor of Central European and Mongol forces in the first half of the Thirteenth century" (PDF). rcin.org.pl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-30.

- ↑ Haslund, Henning. In Secret Mongolia, p. 112.

- ↑ Haslund, Henning. In Secret Mongolia, p. 113.

- ↑ Khan, Paul. Secret History of the Mongols: The Origin of Genghis Khan, p. 108.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Tim Cope - riding from Mongolia to Hungary!". Thelongridersguild.com. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ "Mongolian tacks". lh3.ggpht.com.

- 1 2 Cheng. P. (1984) Livestock breeds of China. Animal Production and Health Paper 46 (E, F, S). Publ. by FAO, Rome, 217 pp.

- 1 2 Cleaves. The Secret History of the Mongols, p. 133.

- 1 2 3 Jeffrey Hays. "Mongol Army: Tactics, Weapons, Revenge And Terror". Facts and Details. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- 1 2 3 "Full text of "The journey of William of Rubruck to the eastern parts of the world, 1253-55"". 1900.

- 1 2 http://hwcdn.libsyn.com/p/e/2/a/e2a1d0358bc915f8/dchha43_Wrath_of_the_Khans_I.mp3?c_id=4619666&expiration=1407651729&hwt=420e072218ce055f8949bfc72e019661%5B%5D

- ↑ "Full text of "The texts and versions of John de Plano Carpini and William de Rubruquis, as printed for the first time by Hakluyt in 1598, together with some shorter pieces; edited by C. Raymond Beazley"". 1903.

- ↑ "Mongol Documents". Archived from the original on 2014-09-07. Retrieved 2014-09-06.

- ↑ Tomoko Nakamura. "Fluctuations in the value of horses in Mongolia before and after socialism" (PDF). arcticcentre.ulapland.fi. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-18. Retrieved 2014-08-30.

- ↑ Cleaves. The Secret History of the Mongols, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 Swietoslawski, W. "A confrontation between two worlds: the arms and armor of Central European and Mongol forces in the first half of the Thirteenth century" (PDF). rcin.org.pl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-30.

- ↑ http://www.amphi.com/media/4226193/genghis%20khan%20-weatherford%20selections.pdf%5B%5D

- ↑ Hoang, Michel. Genghis Khan, p. 258.

- ↑ "All the Khan's Horses" by Morris Rossabi" (PDF). afe.easia.columbia.edu.

- ↑ "Mongolian Fighting Tactics". secure-hwcdn.libsyn.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols". Depts.washington.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ MongolPeace (2010-05-28). "Wild Horses of Mongolia with Julia Roberts 5/5". YouTube. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ Ron Gluckman. "The Alternative Olympics". Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ↑ Davis, Matthew. When Things Get Dark: A Mongolian Winter's Tale, p. 18.

- ↑ Heissig 1980, p. 53-54

- 1 2 Pegg, Carole (2001). Mongolian Music, Dance, & Oral Narrative: Performing Diverse Identities. University of Washington Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 9780295981123. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ "Geser Comes Down to Earth (Part 1)". Epic of King Gesar. 18 January 2008.

- 1 2 "My Life in Mongolia". WordPress. January 10, 2009. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ↑ "Tale #3 – The Legend of Khokhoo Namjil | Telling all kinds of tales". Taletellerin.wordpress.com. 2010-04-18. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ "Tale #42 – The Two Good Horses | Telling all kinds of tales". Taletellerin.wordpress.com. 28 May 2010. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ Haslund, Henning. In Secret Mongolia, p. 112.

- ↑ Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe, p. 53

- ↑ Gejin, Chao (1997). "Mongolian Oral Epic Poetry: An Overview" (PDF). journal.oraltradition.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-15. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 He Dexiu Translated by Pan Zhongming, 2011. The Epic of Jangar.

- 1 2 "The Society and Its Environment" (PDF). www.marines.mil.

- ↑ Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe, p. 54, 58.

- ↑ Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe, p. 130.

- ↑ John Masson Smith, Jr. "Dietary Decadence and Dynastic Decline in the Mongol Empire" (PDF). afe.easia.columbia.edu.

- ↑ Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe, p. 60.

- ↑ "The Mongolian Bow". Coldsiberia.org. 2002-12-27. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ "Ancient Mongolian Weaponry - Armor". Ryanwolfe.weebly.com. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ Bruun, Ole. Precious Steppe, p. 62.

- ↑ "Biden Receives Mongolian Horse, Names It 'Celtic' - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. 2011-08-22. Retrieved 2014-08-25.