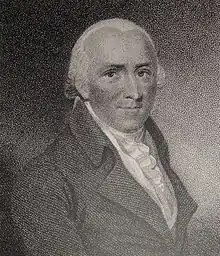

Humphry Repton (21 April 1752 – 24 March 1818) was the last great designer of the classic phase of the English landscape garden, often regarded as the successor to Capability Brown. His style is thought of as the precursor of the more intricate and eclectic styles of the 19th century. His first name is often incorrectly spelt "Humphrey".

Unlike Brown and other famous predecessors, he only worked as a designer, not the contractor for executing his designs, and therefore made much less money. Many of his famous sketches with folding sections survive; these gave "before and after" views for his clients. He appears to be the first person to describe himself (on his business card) as a landscape gardener.

Biography

Early life

Repton was born in Bury St Edmunds, the son of a collector of excise, John Repton, and Martha (née Fitch).[1] In 1762, his father set up a transport business in Norwich, where Humphry attended Norwich Grammar School. At age twelve, he was sent to the Netherlands to learn Dutch and prepare for a career as a merchant. However, Repton was befriended by a wealthy Dutch family and the trip may have done more to stimulate his interest in 'polite' pursuits such as sketching and gardening.

Returning to Norwich, Repton was apprenticed to a textile merchant, then, after marriage to Mary Clarke in 1773, set up in the business himself. He was not successful, and when his parents died in 1778 used his modest legacy to move to a small country estate at Sustead, near Cromer in Norfolk. Repton tried his hand as a journalist, dramatist, artist, political agent, and as confidential secretary to his neighbour William Windham of Felbrigg Hall during Windham's very brief stint as Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Repton also joined John Palmer in a venture to reform the mail-coach system, but while the scheme ultimately made Palmer's fortune, Repton again lost money.

Repton's childhood friend was the botanist James Edward Smith, who encouraged him to study botany and gardening; Smith reproduces a long letter from Repton in his Letter and Correspondence. He was given access to the library of Windham to read its works on botany.[1]

Landscape gardener

His capital dwindling, Repton moved to a modest cottage at Hare Street near Romford in Essex. In 1788, aged 36 and with four children and no secure income, he hit on the idea of combining his sketching skills with his limited experience of laying out grounds at Sustead to become a 'landscape gardener' (a term he himself coined). Since the death of Capability Brown in 1783, no one figure dominated English garden design; Repton was ambitious to fill this gap and sent circulars round his contacts in the upper classes advertising his services. He was at first an avid defender of Brown's views, contrasted with those of Richard Payne Knight and Uvedale Price, but later adopted a moderate position.[1] His first paid commission was Catton Park, to the north of Norwich, in 1788.

That Repton, with no real experience of practical horticulture, became an overnight success, is a tribute to his undeniable talent, but also to the unique way he presented his work. To help clients visualise his designs, Repton produced 'Red Books' (so called for their binding) with explanatory text and watercolours with a system of overlays to show 'before' and 'after' views. In this he differed from Capability Brown, who worked almost exclusively with plans and rarely illustrated or wrote about his work. Repton's overlays were soon copied by the Philadelphian Bernard M'Mahon in his 1806 American Gardener's Calendar.[2]

To understand what was unique about Repton it is useful to examine how he differed from Brown in more detail. Brown worked for many of the wealthiest aristocrats in Britain, carving huge landscape parks out of old formal gardens and agricultural land. While Repton worked for equally important clients, such as the Dukes of Bedford and Portland, he was usually fine-tuning earlier work, often that of Brown himself. Where Repton got the chance to lay out grounds from scratch it was generally on a much more modest scale. On these smaller estates, where Brown would have surrounded the park with a continuous perimeter belt, Repton cut vistas through to 'borrowed' items such as church towers, making them seem part of the designed landscape (coincidentally a concept common in East Asian gardening). He contrived approach drives and lodges to enhance impressions of size and importance, and even introduced monogrammed milestones on the roads around some estates, for which he was satirised by Thomas Love Peacock as 'Marmaduke Milestone, esquire, a Picturesque Landscape Gardener' in Headlong Hall.

Around 1787, Richard Page (1748-1803), landowner of Sudbury, to the west of Wembley decided to convert the Page family home 'Wellers' into a country seat and turn the fields around it into a private estate. In 1792 Page employed Humphry Repton, by then famous as a landscape architect, to convert the previous farmland into wooded parkland and to make improvements to the house.[3] Repton often called the areas he landscaped 'parks', and so it is to Repton that Wembley Park owes its name. The original site that Repton so transformed was later built on in the construction of the short-lived Watkin's Tower, intended to be taller than the Eiffel Tower in Paris.[4] The area landscaped by Repton was larger than the current Wembley Park. It included the southern slopes of Barn Hill to the north, where Repton planted trees and started building a 'prospect house' – a Gothic tower offering a view over the parkland.[3][5][6] Repton may also have designed the thatched lodge that survives on Wembley Hill Road, to the west of Wembley Park. It is in the cottage orné style frequently used by Repton. Regrettably, Repton's Red Book for Wembley Park, which would give a definitive answer, has not survived.[5][7]

Capability Brown was a large-scale contractor, who not only designed, but also arranged the realisation of his work. By contrast, Repton acted as a consultant, charging for his Red Books and sometimes staking out the ground, but leaving his client to arrange the actual execution. Thus many of Repton's 400 or so designs remained wholly or partially unexecuted and, while Brown became very wealthy, Repton's income was never more than comfortable.

Early in his career, Repton defended Brown's reputation during the 'picturesque controversy'. In 1794 Richard Payne Knight and Uvedale Price simultaneously published vicious attacks on the 'meagre genius of the bare and bald', criticising his smooth, serpentine curves as bland and unnatural and championing rugged and intricate designs, composed according to 'picturesque' principles of landscape painting. Repton's defence of Brown rested partly on the impracticality of many picturesque ideas; as a professional, Repton had to produce practical and useful designs for his clients.

Paradoxically, however, as his career progressed Repton drew more and more on picturesque ideas. One major criticism of Brown's landscapes was the lack of a formal setting for the house, with rolling lawns sweeping right up to the front door. Repton re-introduced formal terraces, balustrades, trellis work and flower gardens around the house in a way that became common practice in the nineteenth century. He also designed one of the most famous 'picturesque' landscapes in Britain at Blaise Castle, near Bristol. At Woburn Abbey, Repton foreshadowed another nineteenth-century development, creating themed garden areas including a Chinese garden, American garden, arboretum and forcing garden. At Stoneleigh Abbey in 1808, Repton foreshadowed another nineteenth-century development, creating a perfect cricket pitch called 'home lawn' in front of the west wing, and a bowling green lawn between the gatehouse and the house.

Success at Woburn earned him a further commission from the Duke of Bedford. He designed the central gardens in Russell Square, the centrepiece of the Bloomsbury development. The gardens were restored with the additional help of archaeological investigation and archive photographs, to the original plans and are now listed as Grade II by Historic England. The square was to be a flagship commission for Repton and was only one of three within the central London.

Buildings played an important part in many of Repton's landscapes. In the 1790s he often worked with the relatively unknown architect John Nash, whose loose compositions suited Repton's style. Nash benefited greatly from the exposure, while Repton received a commission on building work. Around 1800, however, the two fell out, probably over Nash's refusal to credit the work of Repton's architect son John Adey Repton. Thereafter John Adey and Repton's younger son George Stanley Repton often worked with their father, although George continued to work in Nash's office as well. It must have been particularly painful for Repton when Nash secured the prestigious work to remodel the Royal Pavilion at Brighton for the Prince Regent, for which Repton himself submitted innovative proposals in an Indian style.

Death and legacy

On 29 November 1811[8] Repton suffered a serious carriage accident which often left him needing to use a wheelchair for mobility. He died at age 65 in 1818 and is buried in the graveyard of the Church of St Michael, Aylsham, Norfolk.[9]

Three roads close to the vicinity of his cottage at Hare Street (now renamed Main Road) in the Gidea Park area of Romford were named after him; Repton Avenue, Repton Gardens and Repton Drive, respectively. A plaque was unveiled on the former site of his cottage on 19 April 1969. The cottage was long since demolished and a branch of Lloyds TSB is situated on the junction of Hare Street and Balgores Lane.[10]

In addition to his innovations in landscape architecture, Repton's 1803 quote "the thorn is the mother of the oak" has become a tenet of rewilding, where thorny plants are used to protect young native saplings from overbrowsing by rabbits and deer.[11]

Publications

Repton published three major books on garden design: Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening (1795), Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803), and Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1816). These drew on material and techniques used in the Red Books.

Several lesser works were also published, including a posthumous collection edited by John Claudius Loudon, despite having severely criticised his approach to gardens.[1]

His published titles were:[1]

- Hundreds of North and South Erpingham, a part of the History of Norfolk, 1781, vol. iii. I

- Variety, a Collection of Essays [anon. By Repton and a few friends], 1788.

- The Bee: a Critique on Paintings at Somerset House, 1788.

- The Bee; or a Companion to the Shakespeare Gallery, 1789.

- Letter to Uvedale Price, 1794.

- Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening, 1794. This volume contained details, with numerous illustrations, of the different gardens and plantations which he had formed. He defends himself in chap. vii. and in an appendix from the criticisms of Knight and Price, and reprints his Letter to Uvedale Price. Only 250 copies were printed, and the work has fetched more than four times the original price.

- Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening,’ 1803.

- Odd Whims and Miscellanies, 1804, 2 vols. They were dedicated to Windham. Some of the essays in Variety were reprinted in this collection, and in the second volume is a comedy of Odd Whims, which was played at Ipswich.

- An Inquiry into the Changes of Taste in Landscape Gardening, with some Observations on its Theory and Practice, 1806; it also included his letter to Price.

- Designs for the Pavilion at Brighton, 1808. He was assisted in this by his sons, John Adey and George Stanley Repton. The plans were approved by the Prince of Wales, but, through want of funds, were not carried out.

- On the Introduction of Indian Architecture and Gardening, 1808.

- Fragments on Landscape Gardening, with some Remarks on Grecian and Gothic Architecture, 1816. In this work his son, J. A. Repton, gave him assistance.

Repton contributed to the Transactions of the Linnean Society, xi. 27, a paper "On the supposed Effect of Ivy upon Trees."

List of gardens

Repton produced designs for the grounds of many of the foremost country houses in England, Scotland and Wales:

- Abington Lodge[12]

- Antony House

- Ashridge House

- Ashton Court

- Attingham Park

- Babworth Hall

- Bayham Abbey

- Blaise Castle

- Bolwick Hall

- Bracondale Lodge[13]

- Broke Hall

- Brondesbury Park

- Buckhurst Park

- Burley-on-the-Hill

- Cassiobury Park

- Catton Park, Old Catton, Norwich

- Claybury Park, Essex

- Clumber Park

- Cobham Hall

- Coombe Park, Whitchurch-on-Thames

- Corsham Court

- Courteenhall House

- Crewe Hall

- Culford Hall, now Culford School

- Dagnam Park, Essex

- Dyrham Park

- East India Company College now Haileybury

- Endsleigh House

- Finedon Hall

- Gosfield Place[14]

- Grovelands Park

- Gunton Hall

- Hampstead Heath

- Hanslope Park

- Harewood House

- Hatchlands Park

- Holkham Hall[15]

- Honing Hall

- Highams Park, Woodford

- Hylands House, Chelmsford

- Kenwood House

- Kensington Gardens, alterations[1]

- Kidbrooke Park, now Michael Hall School

- Leigh Court

- Longleat House

- Moggerhanger Park

- Oldbury Court Estate

- Plas Newydd

- Pentillie

- Rode Hall

- Royal Pavilion at Brighton

- Royal Fort, Bristol

- Rudding Park, Harrogate

- Russell Square, Bloomsbury

- Saling Grove, Great Saling, Essex

- Sarsden

- Scrivelsby

- Shardeloes

- Sheringham Park

- Silwood Park

- Stanage Park

- Stanmer Park

- Stansted Hall

- St. John's Park, Ryde, Isle of Wight

- Stoke Park, Buckinghamshire

- Stoneleigh Abbey

- Stubbers, North Ockendon

- Sufton Court, Herefordshire

- Sundridge Park[16]

- Tatton Park

- Thoresby Park

- Trent Park

- Trewarthenick, Cornwall

- Uppark

- Valleyfield, Fife

- Wanstead Park

- Waresley Park

- Warley Woods

- Warren House, Loughton

- Wembley Park

- West Wycombe Park

- Wingerworth Hall

- Woburn Abbey

Literature

- Mansfield Park by Jane Austen reference to Repton, Chapter 6.

- Arcadia by Tom Stoppard reference to Repton and his 'Red Books', Act 1, Scene 1 (stage directions).

Exhibitions

- Permanent Repton exhibit including facsimile of his Red Book at Sheringham Park in Norfolk.

- Repton bicentenary exhibition at Woburn Abbey during 2018.

- "Repton Revealed: The Art of Landscape Gardening" at The Garden Museum, London showing 23 of Repton's Red Books. 24 October 2018 until 3 February 2019

Bicentenary celebrations in 2018

The Gardens Trust was awarded a Heritage Lottery Fund grant to run a ‘Sharing Repton’ project in 2018–19, working with volunteers to deliver five projects aimed at including participation from local communities, based around five Repton sites across the country. The project took place at Kenwood, London, with London Parks and Gardens Trust and English Heritage; Wicksteed Park, Kettering, with Northamptonshire Gardens Trust; Catton Park, with Norfolk Gardens Trust and Broadland District Council; Blaise Castle, Bristol, with Avon Gardens Trust, and Warley Woods in the Black Country.[17] A record of the project and the resources developed to make garden history more publicly accessible were published in 2020.[18]

Historic England have added Humphry Repton's landscapes to their interactive map of aerial photography of Designed Landscapes [19] and commissioned Hardy Plants and Plantings for Repton and Late Georgian Gardens (1780-1820) which draws on research carried out on plants and planting schemes for late Georgian gardens (1780–1820) and conservation projects, intended to provide a plant list as a starting point for researchers and those restoring gardens of this period.[20]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Courtney, William Prideaux (1896). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 48. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ Library Company of Philadelphia

- 1 2 Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 155–61.

- ↑ Grant, Philip. "Wembley Park – its story up to 1922" (PDF). Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- 1 2 Williams, Cunnington and Hewlett, Leslie R., Win and Geoffrey (1985). "Evidence for a Surviving Humphry Repton Landscape: Barnhills Park, Wembley". Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. 36: 189–202.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "London Gardens Online". www.londongardensonline.org.uk. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ "Check out this property for sale on Rightmove!". Rightmove.co.uk. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ "Humphrey Repton filled the boots of Capability Brown". Look and Learn. 29 September 1973. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ↑ "Second Humphry Repton memorial lecture at Aylsham church", North Norfolk News, 26 April 2019.

- ↑ Georgina Green (19 March 2018). "Humphry Repton's links to Ilford, Wanstead and Woodford". Ilford Recorder. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ↑ Ian D. Rotherham (2013). Trees, Forested Landscapes and Grazing Animals: A European Perspective on Woodlands and Grazed Treescapes. Routledge. p. 383. ISBN 9781136242212.

- ↑ "A Grade II listed building in Great Abington, Cambridgeshire". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ↑ "Repton Property Developments". Repton Homes. All rights reserved. 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

The original 'landscape gardener', Repton affected positive change on a landscape scale and that is a fine ambition for these times also. Humphry Repton has a long affiliation with Norfolk: he lived here as a child, attended school in Norwich and many of his commissions were in Norfolk, including Bracondale Lodge.

- ↑ Bettley, James; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2007). Essex. Yale University Press. p. 381. ISBN 978-0300116144. Retrieved 3 August 2011

- ↑ "The gardener meets a marketing genius". Coke Estates Limited. 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

Similarly, after the estate had been inherited by Thomas William Coke (Coke of Norfolk) the fashions in landscapes had changed and after a period of focus elsewhere on the estate, a new designer was sought: Humphry Repton.

- ↑ "Parks and Gardens UK". Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2011

- ↑ "Sharing Repton - The Gardens Trust". The Gardens Trust. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ "Sharing Repton: Audience Development Project". The Gardens Trust. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ↑ "ArcGIS Web Application". services.historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ↑ "Research Department Reports". research.historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

Further reading

- Amherst, Alicia (2006) [1910]. A History of Gardening in England (3rd ed.). Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9781428636804.

- Bate, Sally, Savage, Rachel and Williamson, Tom (eds). (2018) Humphry Repton in Norfolk, Norfolk Gardens Trust.

- Blomfield, Sir F. Reginald; Thomas, Inigo, Illustrator (1972) [1901]. The Formal Garden in England, 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan and Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Carter, George; Goode, Patrick; Laurie, Kedrun (1982). Humphry Repton Landscape Gardener 1752–1818. Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts.

- Clifford, Derek (1967). A History of Garden Design (2nd ed.). New York: Praeger.

- Daniels, Stephen (1999). Humphry Repton: landscape gardening and the geography of Georgian England. Yale. ISBN 9780300079647.

- Eyres, Patrick and Lynch, Karen (2018). On The Spot: The Yorkshire Red Books of Humphry Repton, landscape gardener. New Arcadian Press.

- Flood, Susan and Williamson, Tom (2018). Humphry Repton in Hertfordshire. ISBN 978-1-909291-98-0.

- Gothein, Marie-Luise Schröeter (1863–1931); Wright, Walter P. (1864–1940); Archer-Hind, Laura; Alden Hopkins Collection (1928) [1910]. History of Garden Art. Vol. 2. London & Toronto, New York: J. M. Dent; 1928 Dutton. ISBN 978-3-424-00935-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) 945 pages Publisher: Hacker Art Books; Facsimile edition (June 1972) ISBN 0878170081; ISBN 978-0878170081. - Gothein, Marie. Geschichte der Gartenkunst. München: Diederichs, 1988 ISBN 978-3-424-00935-4.

- Hadfield, Miles (1960). Gardening in Britain. Newton, Mass: Country Life.

- Hussey, Christopher (1967). English Gardens and Landscapes, 1700–1750. Country Life.

- Hyams, Edward S.; Smith, Edwin, photos (1964). The English Garden. New York: H.N. Abrams.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - London Parks & Gardens Trust (2018). REPTON IN LONDON: The Gardens and Landscapes of Humphry Repton (1752-1818) in the London Boroughs.

- Rogger, André (2007). Landscapes of Taste: The Art of Humphry Repton's Red Books. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415415033.

- Rutherford, Sarah (2018). Hardy Plants and Plantings for Repton and Late Georgian Gardens (1780-1820) Historic England

- Rutherford, Sarah (ed.) (2018) Humphry Repton in Buckinghamshire and Beyond. Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust

- Stroud, Dorothy (1962). Humphry Repton. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - de Weryha-Wysoczański, Chevalier Rafael (2004). Strategien des Privaten. Zum Landschaftspark von Humphry Repton und Fürst Pückler. Berlin. ISBN 3-86504-056-X.

- Williamson, Tom (1995). Polite landscapes: gardens and society in eighteenth century England. Sutton.

External links

- About Britain. "Bayham Abbey"

- Great British Gardens. "Clumber Park, Worksop"

- Grewe, Armin Homepage. "Longleat House"

- Randolph Caldecott Society. "Rode Hall"

- "Stoneleigh Abbey"

- Landscape Architecture University of Oregon. "Humphrey Repton"

- Humphry Repton architectural and landscape designs, 1807-1813 Finding Aid of collection at the Getty Research Institute

- Humphry Repton’s Red Book for Waresley Park in Huntingdonshire. Digitised copy on the RHS Digital Collections website