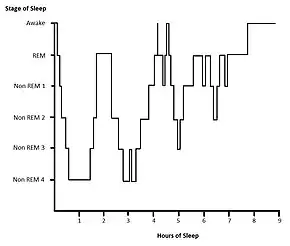

Here, both stage 3 and stage 4 are shown; these are often combined as stage 3.

A hypnogram is a form of polysomnography; it is a graph that represents the stages of sleep as a function of time. It was developed as an easy way to present the recordings of the brain wave activity from an electroencephalogram (EEG) during a period of sleep. It allows the different stages of sleep: rapid eye movement sleep (REM) and non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM) to be identified during the sleep cycle. NREM sleep can be further classified into NREM stage 1, 2 and 3. The previously considered 4th stage of NREM sleep has been included within stage 3; this stage is also called slow wave sleep (SWS) and is the deepest stage of sleep.[1]

Method

.jpg.webp)

Hypnograms are usually obtained by visually scoring the recordings from electroencephalogram (EEGs), electrooculography (EOGs) and electromyography (EMGs).[2]

The output from these three sources is recorded simultaneously on a graph by a monitor or computer as a hypnogram. Certain frequencies displayed by EEGs, EOGs and EMGs are characteristic and determine what stage of sleep or wake the subject is in. There is a protocol defined by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) for sleep scoring, whereby the sleep or wake state is recorded in 30-second epochs.[3] Prior to this the Rechtschaffen and Kales (RK) rules were used to classify sleep stages.[4]

Output

Normal sleep

Cycles of REM and non-REM stages make up sleep. A normal healthy adult requires 7–9 hours of sleep per night. The number of hours of sleep is variable, however the proportion of sleep spent in a particular stage remains mostly consistent; healthy adults normally spend 20–25% of their sleep in REM sleep.[5] During rest following a sleep-deprived state, there is a period of rebound sleep which has longer and deeper episodes of SWS to make up for the lack of sleep.[6]

On a hypnogram, a sleep cycle is usually around 90 minutes and there are four to six cycles of REM/NREM stages that occur during a major period of sleep. Most SWS occurs in the first one or two cycles; this is the deepest period of sleep. The second half of the sleeping period contains most REM sleep and little or no SWS and may contain brief periods of wakefulness which can be recorded but are not usually perceived.[7] The stage that occurs before waking is normally REM sleep.[8]

Hypnograms for healthy persons vary slightly according to age, emotional state, and environmental factors.[9]

Disrupted sleep

Sleep architecture can be evaluated using hypnograms, demonstrating irregular sleeping patterns associated with sleep disorders. Disruptions or irregularities to the normal sleep cycle or sleep stage transitions can be detected; for example a hypnogram can show that in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) the stability of transition between REM and NREM stages is disrupted.[10]

The effects of certain medications on sleep architecture can be visualised on a hypnogram. For example, the anticonvulsant Phenytoin (PHT) can be seen to disrupt sleep by increasing the duration of NREM stage 1 and decreasing the duration of SWS; whereas the drug Gabapentin is seen to revive sleep by increasing the duration of SWS.[11]

Analysis

The main use of a hypnogram is as a qualitative method to visualise the time period of each stage of sleep, as well as the number of transitions between stages. Hypnograms are rarely used to provide quantitative data, however it has been suggested that statistical evaluation can be carried out using multistate survival analysis and log-linear models to provide numerical significance.[12]

Limitations

The restrictions of measuring sleep at short 30-second epochs limits the ability to record events shorter than 30 seconds; hence, the macrostructure of sleep can be evaluated while the microstructure is not. The sleep process is smoothened out in hypnogram results unlike it occurs naturally. Also some specific features of sleep such as sleep spindles and K complexes may not be defined in the hypnogram; this is particularly true for sleep scoring that is automated.[13]

The method of obtaining the data used in a hypnogram is restricted to the input from an EEG, EOG or EMG. The interval of recording may include features from several stages, in which case it is recorded as the stage whose features occupy the recording for the longest duration. For this reason, the stage of sleep may be misrepresented on the hypnogram.

Research directions

Suggestions to improve the automated output of hypnograms to provide more reliable and accurate results include increasing the measures of sleep, for example by additionally measuring sleep with an electrocardiogram (ECG).[14] Another advancement involves combining hypnograms with color density spectral arrays to improve the quality of sleep analysis.[15]

References

- ↑ Silber MH, Ancoli-Israel S, Bonnet MH, Chokroverty S, Grigg-Damberger MM, et al. (2007). "The visual scoring of sleep in adults". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 3 (2): 121–31. doi:10.5664/jcsm.26814. PMID 17557422.

- ↑ Cabiddu R, Cerutti S, Viardot G, Werner S, Bianchi AM (2012). "Modulation of the Sympatho-Vagal Balance during Sleep: Frequency Domain Study of Heart Rate Variability and Respiration". Front Physiol. 3: 45. doi:10.3389/fphys.2012.00045. PMC 3299415. PMID 22416233.

- ↑ McGrogan N, Braithwaite E, Tarassenko L (2001). "BioSleep: A comprehensive sleep analysis system". 2001 Conference Proceedings of the 23rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Vol. 2. pp. 1608–11. doi:10.1109/IEMBS.2001.1020520. ISBN 978-0-7803-7211-5. S2CID 2966203.

- ↑ Danker-Hopfe H, Anderer P, Zeitlhofer J, et al. (March 2009). "Interrater reliability for sleep scoring according to the Rechtschaffen & Kales and the new AASM standard". Journal of Sleep Research. 18 (1): 74–84. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00700.x. PMID 19250176. S2CID 38993280.

- ↑ Lee-Chiong TL (2009). Sleep Medicine Essentials. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 2. ISBN 978-0470195666.

- ↑ Ferrara M, De Gennaro L, Casagrande M, Bertini M (July 2000). "Selective slow-wave sleep deprivation and time-of-night effects on cognitive performance upon awakening". Psychophysiology. 37 (4): 440–6. doi:10.1111/1469-8986.3740440. PMID 10934902.

- ↑ Lee-Chiong TL (2009). Sleep Medicine Essentials. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0470195666.

- ↑ Merica H, Fortune RD (December 2004). "State transitions between wake and sleep, and within the ultradian cycle, with focus on the link to neuronal activity". Sleep Med Rev. 8 (6): 473–85. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2004.06.006. PMID 15556379.

- ↑ Wilson S, Nutt D (1999). "Treatment of sleep disorders in adults". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 5: 11–18. doi:10.1192/apt.5.1.11.

- ↑ Bianchi MT, Cash SS, Mietus J, Peng CK, Thomas R (2010). "Obstructive sleep apnea alters sleep stage transition dynamics". PLOS ONE. 5 (6): e11356. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511356B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011356. PMC 2893208. PMID 20596541.

- ↑ Legros B, Bazil CW (January 2003). "Effects of antiepileptic drugs on sleep architecture: a pilot study". Sleep Med. 4 (1): 51–5. doi:10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00217-4. PMID 14592360.

- ↑ Swihart BJ, Caffo B, Bandeen-Roche K, Punjabi NM (August 2008). "Characterizing sleep structure using the hypnogram". J Clin Sleep Med. 4 (4): 349–55. doi:10.5664/jcsm.27236. PMC 2542492. PMID 18763427.

- ↑ Barcaro U, Navona C, Belloli S, Bonanni E, Gneri C, Murri L (May 1998). "A simple method for the quantitative description of sleep microstructure". Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 106 (5): 429–32. doi:10.1016/S0013-4694(98)00008-X. PMID 9680156.

- ↑ Krakovská A, Mezeiová K (September 2011). "Automatic sleep scoring: a search for an optimal combination of measures". Artif Intell Med. 53 (1): 25–33. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2011.06.004. PMID 21742473.

- ↑ Pracki T, Pracka D, Ziółkowska-Kochan M, Tafll-Klawe M, Szota A, Wiłkość M (2008). "The modified Color Density Spectral Array--an alternative method for sleep presentation". Acta Neurobiol Exp. 68 (4): 516–8. PMID 19112475.