Imperial Free City of Trieste | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1382–1809 1849–1922 | |||||||||||||

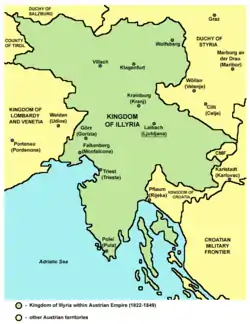

Map of the Austrian Littoral | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Trieste 45°38′N 13°48′E / 45.633°N 13.800°E | ||||||||||||

| Government | Free city | ||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||

| Legislature | Diet of Trieste | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | |||||||||||||

• Occupied by Venice | 1369–72 | ||||||||||||

• Ceded to Austria | October 1382 | ||||||||||||

| 14 October 1809 | |||||||||||||

• Austrian reconquest | 1813 | ||||||||||||

| 1816–49 | |||||||||||||

| 4 November 1918 | |||||||||||||

| 12 November 1920 | |||||||||||||

| 28 October 1922 | |||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1910 | 95 km2 (37 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1910 | 229995 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

The Imperial Free City of Trieste and its Territory (German: Reichsunmittelbare Stadt Triest und ihr Gebiet, Italian: Città Imperiale di Trieste e Dintorni) was a possession of the Habsburg monarchy in the Holy Roman Empire from the 14th century to 1806, a constituent part of the German Confederation and the Austrian Littoral from 1849 to 1920, and part of the Italian Julian March until 1922. In 1719 it was declared a free port by Emperor Charles VI; the construction of the Austrian Southern Railway (1841–57) turned it into a bustling seaport, through which much of the exports and imports of the Austrian Lands were channelled. The city administration and economy were dominated by the city's Italian population element; Italian was the language of administration and jurisdiction. In the later 19th and early 20th century, the city attracted the immigration of workers from the city's hinterlands, many of whom were speakers of Slovene.

History

Background

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, Trieste was a Byzantine military outpost. In 567 AD the city was destroyed by the Lombards, in the course of their invasion of northern Italy. In 788 it became part of the Frankish kingdom, under the authority of their count-bishop. From 1081 the city came loosely under the Patriarchate of Aquileia, developing into a free commune by the end of the 12th century.

After two centuries of war, Trieste came with the signing of a peace treaty on 30 October 1370 in front of St. Bartholomew's Church in the village of Šiška (apud Sisciam) (now part of Ljubljana) under the Republic of Venice.[1] The Venetians retained the town until 1378, when it became the property of the Patriarchate of Aquileia.[2] Discontent with the patriarch's rule, the main citizens of Trieste in 1382 petitioned Leopold III of Habsburg, Duke of Austria to become part of his domains, in exchange for his defence.[2] This united Charlemagne's southern marches under Habsburg rule,[3] subsequently consolidated as the Austrian Littoral (German: Österreichisches Küstenland).

Trieste in the Holy Roman Empire

Following an unsuccessful Habsburg invasion of Venice in the prelude to the War of the League of Cambrai, the Venetians occupied Trieste again in 1508, and under the terms of the peace were allowed to keep the city. The Habsburg Empire recovered Trieste a little over a year later, however, when conflict resumed. With their acquisition by the Habsburgs, Carniola and the Julian March ceased to act as an east-facing outpost of Italy against the unsettled peoples of the Danube basin, becoming a region of contact between the land-based Austrian domains and the maritime republic of Venice, whose foreign policy depended on control of the Adriatic.[3] Austro-Venetian rivalry over the Adriatic weakened each state's efforts to repel the Ottoman Empire's expansion into the Balkans (which caused many Slavs to flee into the Küstenland, sowing the seeds of future Yugoslav union), and paving the way for the success of Napoleon's invasion.[3]

On the Habsburg's annexation, Trieste had a patriciate, a bishop and his chapter, two municipal chapters totalling 200 people, armed forces and institutions of higher education.[4] Italian irredentism was continually popular — writing in 1917, the Italian nationalist Litta Visconti Arese described the city as:

The last of the Italian Comuni still struggling in the twentieth century against the Germanic Empire and the Invasion of the Barbarians.[5]

Trieste became an important port and trade hub. In June 1717,[4] it was made a free port within the Habsburg Empire by Emperor Charles VI (r. 1711–40), effective from his visit to the city on 10 September 1718,[4] and remained a free port until 1 July 1891, when it was eclipsed by Fiume (now Rijeka).[6] From June 1734, Charles VI began assembling a navy in the city.[4] The reign of Charles VI's successor, Maria Theresa (r. 1740–65), marked the beginning of a flourishing era for the city, starting with her order for the dismantling of the city walls in 1749, in order to allow the freer expansion of the city, and ordering expansive building works and canal dredging.[4]

In 1768, the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann was murdered by a robber in Trieste, while on his way from Vienna to Italy.

French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars

Trieste was occupied by French troops three times during the Napoleonic Wars, in 1797, 1805 and in 1809. Between 1809 and 1813, it was annexed to the Illyrian Provinces, interrupting its status as a free port and causing a loss of the city's autonomy; the municipal autonomy was not restored after the return of the city to the Austrian Empire in 1813. For the French, the Illyrian Provinces provided a military frontier against the remaining Austrian lands and a military base against the Turks, as well as providing distant endowments for Marshals of the Empire.[3]

When Napoleon defeated the Republic of Venice in 1797, he found that Istria was populated by Italians on the coast and in the main cities, but the interior was populated mainly by Croats and Slovenians; this dual ethnicity in the same peninsula created antagonism between Slavs and Italians for the supremacy of Istria, when nationalism first started to rise after Napoleon's fall. The restoration of Istria to the Austrian Empire was confirmed at the Congress of Vienna, but a nationalistic feud began to develop between the Slavs and the Italians.[7]

Trieste in the Austrian Empire and Austria–Hungary

Following the Napoleonic Wars, Trieste continued to prosper as the free imperial city of Trieste (German: Reichsunmittelbare Stadt Triest), a status that granted economic freedom, but limited its political self-government. The city's role as main Austrian trading port and shipbuilding centre was later emphasised with the foundation of the merchant shipping line Austrian Lloyd in 1836, whose headquarters stood at the corner of the Piazza Grande and Sanità. By 1913, Austrian Lloyd had a fleet of 62 ships comprising a total of 236,000 tons.[8] With the introduction of the constitutionalism in the Austrian Empire in 1860, the municipal autonomy of the city was restored, with Trieste becoming capital of the Adriatisches Küstenland, the Austrian Littoral region.

In the later part of the 19th century, Pope Leo XIII considered moving his residence to Trieste (or to Salzburg), due to what he considered a hostile anti-Catholic climate in Italy, following the capture of Rome by the newly founded Kingdom of Italy. However, the Austrian monarch Franz Josef I gently rejected this idea.[9]

The modern Austro-Hungarian Navy used Trieste's shipbuilding facilities for construction and as a base. The Austrian acquisition of Lombardy-Veneto (1815–66) meant that Trieste was no longer in a frontier zone,[3] encouraging the construction of the first major trunk railway in the Empire, the Vienna–Trieste Austrian Southern Railway (German: Südbahn), was completed in 1857, a valuable asset for trade and the supply of coal. The importance of Trieste as a trading and shipbuilding city to the Empire is testified by the expenditure made. The construction of Porto Nuovo cost 29 million crowns over 15 years (1868–83) and in the following decade another 10 million crowns were spent extending the port[3] (roughly equivalent to 12 tons of gold). Up until 1914, over 14 million crowns of subsidies were paid to Austrian shipping companies using Trieste.[3] This investment and railway-building resulted in a rapid expansion of Triestine trade, which peaked in 1913 at over 6 million tons of goods, with the port almost entirely reliant on Austro-Hungarian trade, as opposed to transshipment;[3] even after the Italian acquisition of the city, Trieste continued to be a port for central and southeastern Europe, rather than Italian trade,[3] mainly for coffee, sugar and tropical fruits, wines, oils, cotton, iron, wood and machinery.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Trieste was a buzzing cosmopolitan city frequented by artists and philosophers such as James Joyce, Italo Svevo, Sigmund Freud, Dragotin Kette, Ivan Cankar, Scipio Slataper, and Umberto Saba. The city was the major port of the Austrian Riviera, and perhaps the only real enclave of Mitteleuropa south of the Alps. Viennese architecture and coffeehouses still dominate the streets of Trieste to this day.

End of Austrian Trieste

Together with Trento, Trieste was a main focus of the irredentist movement,[10] which aimed for the annexation to Italy of all the lands they claimed were inhabited by an Italian-speaking population. Many local Italians enrolled voluntarily in the Royal Italian Army (a notable example is the writer Scipio Slataper).[11]

After the end of World War I, the Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved, and many of its border areas, including the Austrian Littoral, were disputed among its successor states. On November 3, 1918, the Armistice of Villa Giusti was signed ending hostilities between Italy and Austria-Hungary. Trieste, with Istria and Gorizia was occupied by the Italian Army after the Austro-Hungarian troops had been ordered to lay down their arms, a day before the Armistice was due to enter into effect, effectively allowing the Italians to claim the region had been taken before the cessation of hostilities (a similar situation occurred in South Tyrol). Trieste was lost to Austria at Saint-Germain-en-Laye and officially annexed to the Kingdom of Italy at Rapallo in 1920. If the Liberal governments ruling Italy at time granted Trieste of its ancient autonomy, maintained most of former Austrian laws, and simply gave a new name to the Austrian Littoral as Julian March (Italian: Venezia Giulia) without any other legal change, Fascist violence which occurred to Socialists and Christian Democrats in other parts of Italy, were suffered by Slovene organizations in Trieste.[12]

The union to Italy brought a loss of importance to the city, as it was now a city on the margin of Italy's map, cut off from its economic hinterland. The Slovene ethnic group (around 25% of the population according to the 1910 census)[13][14][15][16][17][18] suffered persecution by rising Italian Fascism. The period of violent persecution of Slovenes began with riots on 13 April 1920, which were organized as a retaliation for the assault on Italian occupying troops in Split by the local Croatian population. Many Slovene-owned shops and buildings were destroyed during the riots, which culminated when a group of Italian Fascists, led by Francesco Giunta, burned down the Narodni dom ("National Hall"), the community hall of Trieste's Slovenes.

The end of Trieste autonomy was a consequence of the March on Rome in 1922. Immediately after their rose to power, the Fascists abolished the Austrian administrative structure of the Julian March, which was divided between the newly formed Province of Trieste, of which Trieste became a mere municipality, and the Province of Pola; the remainder of the territory was annexed by the Province of Udine.[19]

Demographics

The particular Friulian dialect, called Tergestino, spoken until the beginning of the 19th century, was gradually overcome by the Triestine dialect (with a Venetian base, deriving directly from vulgar Latin) and other languages, including German grammar, Slovene and standard Italian languages. While Triestine was spoken by the largest part of the population, German was the language of the Austrian bureaucracy and Slovene was predominant in the surrounding villages. From the last decades of the 19th century, Slovene language speakers grew steadily, reaching 25% of the overall population of the municipality of Trieste in 1911 (30% of the Austro-Hungarian citizens in Trieste).[17]

According to the 1911 census, the proportion of Slovene speakers amounted to 12.6% in the city centre, 47.6% in the suburbs, and 90.5% in the surroundings.[20] They were the largest ethnic group in 9 of the 19 urban neighborhoods of Trieste, and represented an absolute majority in 7 of them.[20] The Italian speakers, on the other hand, were 60.1% of the population in the city centre, 38.1% in the suburbs, and 6.0% in the surroundings. They were the largest linguistic group in 10 of the 19 urban neighborhoods and represented the majority in 7 of them (including all 6 in the city centre). Of the 11 villages included within the city limits, the Slovene speakers had an overwhelming majority in 10, and the German speakers in one (Miramare).

German speakers amounted to 5% of the city's population, with the highest proportions in the city centre. A small number of the population spoke Serbo-Croatian (around 1.3% in 1911), and the city also counted several other smaller ethnic communities: Czechs, Istro-Romanians, Serbs and Greeks, which mostly assimilated either to the Italian or Slovene-speaking community.

See also

References

- ↑ L'Archeografo triestino (PDF). Classic Reprint Series (in Italian). Vol. 1. Forgotten Books. 1870. p. 298.

- 1 2 Anka Benedetič (1976), "Iz zgodovine Šiške", Javna tribuna (Ljubljana-Šiška) (in Slovenian), vol. 16, no. 130 (Digitalna Knjižnica Slovenije)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A. E. Moodie (February 1943). "The Italo-Yugoslav Boundary". The Geographical Journal. 101 (2): 49–63. doi:10.2307/1789641. JSTOR 1789641.

- 1 2 3 4 5 R Burton (1875). "The port of Trieste, ancient and modern". Foreign and Commonwealth Office Collection. pages 979–86, 996–1006. JSTOR 60235914.

- ↑ The Duke of Litta Visconti Arese, quoting an unnamed source (October 1917). "Unredeemed Italy". The North American Review. 206 (743): 568. JSTOR 25121657.

- ↑ Reşat Kasaba; Çağlar Keyder; Faruk Tabak (Summer 1986). "Eastern Mediterranean Port Cities and Their Bourgeoisies: Merchants, Political Projects, and Nation-States". Review (Fernand Braudel Center). 10 (1): 121–35. JSTOR 40241050.

- ↑ Bernardo Benussi (1997). L'Istria nei suoi due millenni di storia [Istria in its two millennia of history]. Unione Italiana Fiume / Università Popolare di Trieste. p. 63. ISBN 978-88-317-6751-4. OCLC 38131096.

- ↑ Franz Hubmann (1972). Andrew Wheatcroft (ed.). The Habsburg Empire, 1840–1916. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-7230-6.

- ↑ Josef Schmidlin [in German] (1934). Papstgeschichte der neueren Zeit, Vol 1: Papsttum und Päpste im Zeitalter der Restauration (1800–1846) [Papal History in the Modern era, Volume 1: The Papacy and the Popes in the Early Restoration (1800–1846)] (in German). Munich: Kösel-Pustet. p. 414. OCLC 4533637.

- ↑ Glenda Sluga (2001). The Problem of Trieste and the Italo-Yugoslav Border. SUNY Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7914-4823-6.

- ↑ Alberto Mario Banti (1978). "Chapter 2". In Alberto Mario Banti; Paul Ginsborg (eds.). Storia d'Italia, Vol 22: Il Risorgimento [History of Italy, Volume 22: The Risorgimento] (in Italian). Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-16729-5.

- ↑ "90 let od požiga Narodnega doma v Trstu" [90 Years From the Arson of National Hall in Trieste]. Primorski dnevnik (in Slovenian). 2010. pp. 14–15. COBISS 11683661. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ↑ Carlo Schiffrer (1946). Autour de Trieste, point névralgique de l'Europe. Les populations de la Vénetie julienne [Around Trieste, nerve point of Europe. The populations of the Julian March] (in French). Paris: Fasquelle Éditeurs. p. 48. OCLC 22254249.

- ↑ Giampaolo Valdevit (2004). Trieste: Storia di una periferia insicura [Trieste: History of an insecure periphery] (in Italian). Milan: Bruno Mondadori. p. 5. ISBN 978-88-424-9182-8.

- ↑ Angelo Vivante (1945) [1912]. Irredentismo adriatico [Adriatic Irredentism] (in Italian). Florence. pp. 158–164. ISBN 9788878000001.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Carlo Schiffrer (1946). Historic Glance at the Relations between Italians and Slavs in Venezia Giulia. Trieste: Stab. Tip. Nazionale. pp. 25–34.

- 1 2 Pavel Stranj; Vladimir Klemenčič; Ksenija Majovski (1999). Slovensko prebivalstvo Furlanije-Julijske krajine v družbeni in zgodovinski perspektivi [Slovenian population of Friuli-Venezia Giulia in the socio-historical perspective] (in Slovenian). Trieste: Slovenski raziskovalni inštitut. pp. 296–302.

- ↑ Jean-Baptiste Duroselle [in French] (1966). Le conflit de Trieste 1943–1954 [Conflict in Trieste, 1943–1954] (in French). Brussels: Université libre de Bruxelles. pp. 35–41. OCLC 1066087.

- ↑ Royal decree n°53 of January 18, 1923, by King Victor Emmanuel III and Prime Minister Benito Mussolini.

- 1 2 Spezialortsrepertorium der Österreichischen Länder. VII. Österreichisch–Illyrisches Küstenland [Special geographical report of the Austrian Länder VII: Austrian–Illyrian Littoral] (in German). Vienna: Verlag der K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei. 1918.