|

| Inca Empire |

|---|

| Inca society |

| Inca history |

Incan agriculture was the culmination of thousands of years of farming and herding in the high-elevation Andes mountains of South America, the coastal deserts, and the rainforests of the Amazon basin. These three radically different environments were all part of the Inca Empire (1438-1533 CE) and required different technologies for agriculture. Inca agriculture was also characterized by the variety of crops grown, the lack of a market system and money, and the unique mechanisms by which the Incas organized their society. Andean civilization was "pristine"—one of six civilizations worldwide which were indigenous and not derivative from other civilizations.[1] Most Andean crops and domestic animals were likewise pristine—not known to other civilizations. Potatoes and quinoa were among the many unique crops; Camelids (llamas and alpacas) and guinea pigs were the unique domesticated animals.

The Incan civilization[2] was predominantly agricultural. The Incas had to overcome the adversities of the Andean terrain and weather. Their adaptation of agricultural technologies that had been developed by previous cultures allowed the Incas to organize production of a diverse range of crops from the arid coast, the high, cold mountains, and the hot, humid jungle regions, which they were then able to redistribute to villages that did not have access to the other regions. These technological achievements in agriculture would not have been possible without the workforce that was at the disposal of the Inca emperor, called the Sapa Inca, as well as the road system and extensive storage systems (qullqas) that allowed them to harvest and store food and to distribute it throughout their empire.

Environment

The heartland of the Inca Empire was in the high plateaus and mountains of the Andes of Peru. This area is mostly above 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) in elevation and is characterized by low or seasonal precipitation, low temperatures, and thin soils. Freezing temperatures may occur in every month of the year at these altitudes.[3]

Westward from the Andes is the Pacific Ocean, its coast often called the driest desert in the world.[4] Agriculture is only possible with irrigation waters from the many rivers originating in the Andes and crossing the desert to the ocean. Eastward from the Andes are the rugged foothills above the Amazon Basin, an area of abundant rainfall, exuberant vegetation, and tropical or sub-tropical temperatures.

Organization

In the Inca Empire, society was tightly organized. Land was divided in roughly equal shares for the emperor, the state religion, and the farmers themselves. Individual farmers were allocated land by the leader of the ayllu, the kinship group typical of both the Quechua and Aymara speakers of the Andes. The allocations of land to individual farmers depended upon kinship, social status, and number of family members.[5] The farmers were expected to produce their own sustenance from the land they were allocated. Rather than being taxed on their production, farmers were required to work on the lands of the emperor and the state religion for designated periods. On the state lands, the Incas provided the inputs—seeds, fertilizer, and tools—to farmers. The farmers contributed their labor. Communities were essentially self-sufficient, growing a variety of crops, pasturing camelids, and weaving cloth.[6]

Private property existed in the form of royal estates, especially in the Sacred Valley near the Inca capital of Cuzco. Emperors customarily confiscated large quantities of land for their own use and exploitation and the estate was inherited by descendants after the emperor's death. The famous archaeological site of Machu Picchu was a royal estate. The royal estates made use of local labor, but also were staffed by a servant class called yanakunas who were ruled directly by Inca nobles and were outside the ayllu kinship system. In some areas, such as the valley of Cochabamba in Bolivia, state farms were dedicated to the production of maize, the prestige crop of the Incas but one which could not be grown at the higher elevations of the Andes.[7]

In the oasis valleys on the desert coast, the population was more specialized, divided mostly into farmers and fishermen with trade relationships between the two.

Food security

In the Andes, high cool elevations, scarcity of flat land, and climatic uncertainty were major factors influencing farmers. The Incas, the local leaders of the ayllus, and the individual farmers decreased their risk of poor crop years with a variety of measures. The vertical archipelago was a characteristic of Andean and Incan agriculture. Different crops could only be grown in the climates associated with certain elevations and the people of the empire diversified their agricultural production by establishing colonies and reciprocity with populations living at different, usually lower, elevation than the Inca heartland. Also, land allocated to local authorities, the ayllus, was often not contiguous, but rather scattered at different elevations and climates to produce different products. The exchange of products among the scattered lands was carried out on a reciprocal basis rather than being commercially traded.[8]

The Incas placed great emphasis on storing agricultural products, constructing thousands of storage silos (qullqa or qollqas) in every major center of their empire and along their extensive road system.[9] Hillside placements were used to preserve food in storage by utilizing the natural cool air and wind to ventilate both room and floor areas.[9][10] Drainage canals and gravel floors in qollqas helped to keep foodstuffs dry.[9][10] Food could be stored for up to two years in these granaries before spoiling due to the ventilation and drainage.[9] Dried meat (jerky), freeze-dried potatoes (chuño), maize, and quinoa were among the crops stored in large quantities for the provisioning of the Inca army and officialdom and as a hedge against poor crop years. Careful records were kept of the products and quantities stored on the knotted cords, called quipu, which the Incas used in lieu of a written language.

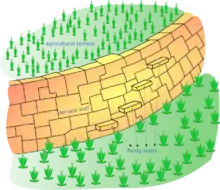

Individual farmers and communities had several techniques of reducing their risk. Farmers usually had many different, scattered plots of land on which they planted a variety of crops. If one or more crops failed, others might be productive.[11] In many areas of the Andes, farmers, communities, and the Inca state constructed agricultural terraces (andenes) to increase the amount of arable land. Andenes also reduced the threat of freezes, increased exposure to sunlight, controlled erosion, and improved the absorption of water and aeration of the soil.[12] The construction and use of andenes for crops enabled agriculture in the Andes to expand into climatically marginal areas.[3] In some areas, raised beds (Waru Waru) were used for many of the same purposes as andenes and also to facilitate drainage.[13]

On the desert coast extensive irrigation works were necessary for agriculture. The population on the coast was more specialized than the highland population with communities of farmers, fishermen, potters, weavers and others. Instead of self-sufficiency trade was extensive among the various producers. Unlike the highlands, the lowlanders utilized shells and gold as a form of money. However, in the coastal communities, the same emphasis on collective management and reciprocity prevailed as in the Andes. The sparsely populated eastern slopes of the Andes enjoyed abundant precipitation and warmer temperatures than the highlands, but also had agriculture challenges such as steep terrain. This region was important for its tropical crops, bird feathers, gold, and wood.[14][15]

The Incas transported agricultural goods by llama caravan. For example, maize grown at the state farm of Cochabamba was transported first to the regional center of Paria. Some was stored there and some was transported on to Cuzco.[16]

Crops

.jpg.webp)

A staple crop grown from about 1,000 meters to 3,900 meters elevation was potatoes.[17] Quinoa was grown from about 2,300 meters to 3,900 meters.[17] Maize was the principal crop grown up to an elevation of 3200 meters commonly and 3,500 meters in favorable locations. Cotton was a major crop near the Pacific Ocean and grown up to elevations of about 1,500 meters. On the eastern slopes of the Andes, coca was grown up to the same elevation, and cassava was a major crop of the Amazon lowlands. Tubers such as oca, mashua and maca were also grown.[18]

In addition to these staple crops the people of the Inca empire cultivated a great variety of fruits, vegetables, spices and medicinal plants. Some of these other foods grown consist of tomatoes, chili peppers, avocadoes and peanuts.[19] Many fruit trees were also utilized in crop production. Banana passionfruit can be grown from 2,000 to 3,200 meters, mountain papaya from 500 to 2,700 meters, naranjilla (or lulo) from 500 to 2,300 meters, and Cape gooseberry from 500 to 2,800 meters.[17]

Animal husbandry

The Incan agriculture system not only included a vast acreage of crops, but also numerous herds, some numbering in the tens of thousands, of animals, some taken by force from conquered enemies.[9] These animals were llamas and alpacas, the dung of which was used to fertilize the crop fields.[9] Llamas and alpacas were usually pastured high up in the Andes above cultivatable land, at 4,000 meters (13,000 ft) elevation and even higher.[20] Llamas and alpacas were very important providing "wool, meat, leather, moveable wealth," and "transportation."[9] The Inca also bred and domesticated ducks and guinea pigs as a source of meat.[21] This mixture of Animal husbandry, especially that of llamas and alpacas, was important to the economy of the Incas.[22]

Farming tools

Inca farmers did not have domesticated animals suitable for agricultural work so they relied on manual tools. These were well adapted to the mountainous terrain of the Andes and to the limited-area of terraces or andenes on which they often built and farmed. Main manual tools used include:

- Chaki taklla,[23] a human-powered foot plough that consists of a wooden pole with a curved sharp point, often made of stone or metal. Across the end of this pole ran another wooden crossbar, on which the farmer could put his foot to sink it into the earth and produce a furrow.[24] This tool is still used in the Andes for plowing, sowing, and building.[25]

- Rawk'ana,[23] a hoe with a thin sheet of wood of chachakuma, no higher than 40 cm. It was used to harvest tubers, to remove weeds and to sow small seeds.

- Waqtana, a Quechua term for a "clod buster"[26]

The chaki taklla, rawk'ana, and waqtana were used by Andean farmers for thousands of years.[26]

Other technologies used to produce foodstuffs include many tools made with sharpened cobble stones, stone or clay.[9] A mortar and pestle was used to grind up grains to be further used in cooking.[9] Stone and clay stoves were used to cook foods over fires from either wood or llama dung.[9] Generally made from cobble stones, farming tools like the hoe, clod breaker and foot plough were used to break up the soil and make it easier to aerate and plant crop seeds.[9][27]

Farming was celebrated with rituals and songs. Teams of seven or eight men, accompanied by the same number of women, would work in line to prepare fields. The men used foot plows, chaki taklla, to break the soil. The women followed, breaking the clods and planting seeds. This work was accompanied by singing and chanting, striking the earth in unison. By one account Spanish priests found the songs so pleasant that they were incorporated into church services.[28]

Land use

Inca farmers learned how to best use the land to maximize agriculture production. This expressed itself in the form of stone terraces to keep the important Andean soil from eroding down the mountain side.[17][29] These terraces also helped to insulate the roots of plants during cold nights and hold in the moisture of the soil, keeping plants growing and producing longer in the high altitudes.[17][29] Tipón was a location in the Inca Empire that was an estate for Incan nobles. It had terrace walls that were anywhere from 6 to 15 feet tall.[30] The Inca often irrigated these terraces by using water melting from nearby glaciers.[31] The Inca transported this freshly melted water to crop fields by building irrigation canals to move the water and cisterns to store the water.[17] Another method that the Inca used to gain more farm land was to drain wetlands in order to get to the rich fertile top soil underneath the shallow water.[9] The Inca also understood the value of crop rotation and planted different crops in the same fields annually replenishing the soil and producing better harvests.[9]

The Incan agricultural terraces at Moray.

The Incan agricultural terraces at Moray. Inca terrace irrigation engineering.

Inca terrace irrigation engineering. Waru waru (or camellon).

Waru waru (or camellon). In desert regions, above and below-ground puquios irrigated crops.

In desert regions, above and below-ground puquios irrigated crops.

Peruvian maize.

Peruvian maize.

See also

References

- ↑ Upton, Gary and von Hagen, Adriana (2015), Encyclopedia of the Incas, New York: Rowand & Littlefield, p. 2. Some scholars cite 6 or 7 pristine civilizations.

- ↑ "Top 5 Ancient Incan Inventions". HowStuffWorks. 2011-01-12. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- 1 2 Guillet, David and others (1987), "Terracing and Irrigation in the Peruvian Highlands," Current Anthropology, Vol. 28, No. 4, pp. 409-410. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ↑ Vesilind, Priit J. (August 2003). "The Driest Place on Earth". National Geographic Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ↑ D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003), The Incas Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, p. 198

- ↑ McEwan, Gordon F. (2006), The Incas: New Perspectives, New York: W. W. Norton & Co., pp. 87-88

- ↑ D'Altroy, pp 74, 85-87; McEwan, pp. 109-110

- ↑ McEwan, pp. 83-85

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Inca Food & Agriculture". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- 1 2 "Storage". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ↑ Earls, John (nd), "The Character of Inca and Andean Agriculture", Pontifica Universidad Catolica del Peru, p. 9, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-17. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed 15 Jan 2017 - ↑ Blossiers Piňedo, Javier, "Agricultura de Laderas a traves de Andenes, Peru, https://web.archive.org/web/20101214103311/http://www.rlc.fao.org/es/tierra/pdf/capta/siste5.pdf, accessed 16 Dec 2016

- ↑ "Raised beds and waru waru cultivation", "4.1 Raised beds and waru waru cultivation". Archived from the original on 2017-01-29. Retrieved 2017-02-22., accessed 15 Jan 2017

- ↑ D'Altroy, pp. 31,204

- ↑ Moseley, Michael E. (2001), The Incas and their Ancestors, London: Thames and Hudson, pp 41, 48-50

- ↑ La Lone, Mary B and La Lone, Darrell E. (1987), "The Inka State in the Southern Highlands: State Administrative and Production Enclaves," Ethnohistory, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 50-51

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Andean agriculture". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 2017-10-05. Retrieved 2017-11-03.

- ↑ "Farming Like the Incas". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2017-11-06.

- ↑ Malpass, Michael A. (2009-04-30). Daily Life in the Inca Empire, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313355493.

- ↑ "What Connects Llamas and Alpacas, Vicunas, and Guanacos?". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 2017-10-14. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- ↑ Malpass, Michael Andrew (2009). Daily life in the Inca empire. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-313-35548-6.

- ↑ McEwan, Gordon F. (2008). The Incas: New Perspectives. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-393-33301-5.

- 1 2 Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary)

- ↑ Inkan Agriculture Archived 2015-01-06 at the Wayback Machine, Qosqo

- ↑ "NameBright - Coming Soon". www.trophort.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- 1 2 Lentz, David Lewis; Imperfect balance: landscape transformations in the Precolumbian Americas, Columbia University Press, 2000, 547pp, p.322 ISBN 978-0-231-11156-0 (retrieved 17 February 2012 via Google Books)

- ↑ Gade, Daniel W. (1992). "Landscape, System, and Identity in the Post-Conquest Andes". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 82 (3): 460–477. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1992.tb01970.x. JSTOR 2563356.

- ↑ D'Altroy. pp 198-199

- 1 2 "Terrace (Step) farming Inca; Advantages and Disadvantages". agrifarmingtips.com. Archived from the original on 2017-11-10. Retrieved 2017-11-10.

- ↑ Wright, Kenneth R. (2006). Tipon: Water Engineering Masterpiece of the Inca Empire. Reston, Virginia: American Society for Civil Engineers. p. 36. ISBN 0-7844-0851-3.

- ↑ Chepstow-Lusty, A. J.; Frogley, M. R.; Bauer, B. S.; Leng, M. J.; Boessenkool, K. P.; Carcaillet, C.; Ali, A. A.; Gioda, A. (2009-07-22). "Putting the rise of the Inca Empire within a climatic and land management context". Clim. Past. 5 (3): 375–388. Bibcode:2009CliPa...5..375C. doi:10.5194/cp-5-375-2009. ISSN 1814-9332. Archived from the original on 2017-09-29.

Sources

- McNeill, W. H. (1999). "How the Potato Changed the World's History". Social Research, 66(1), 67–83.

- Kelly, K. (1965). "Land-Use Regions in the Central and Northern Portions of the Inca Empire". Annals Of The Association Of American Geographers, 55(2), 327–338.

- Maxwell Jr., T. J. (n.d). Agricultural Ceremonies OF THE Central Andes During Four Hundred Years of Spanish Contact. Duke University Press.

Bibliography

- (in Spanish) Rostworowski, María: Enciclopedia Temática: Incas. ISBN 9972-752-00-3.

- (in Spanish) Editorial Sol 90: Historia Universal: América precolombina ISBN 9972-891-79-8.

- (in Spanish) Muxica Editores: Culturas Prehispánicas ISBN 9972-617-10-6.

- Rivero Luque: The use of the chakitaqlla in the Andes, 1987.