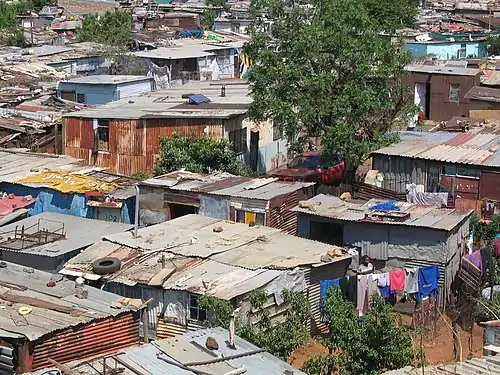

Informal housing or informal settlement can include any form of housing, shelter, or settlement (or lack thereof) which is illegal, falls outside of government control or regulation, or is not afforded protection by the state.[1] As such, the informal housing industry is part of the informal sector.[2]

To have informal housing status is to exist in "a state of deregulation, one where the ownership, use, and purpose of land cannot be fixed and mapped according to any prescribed set of regulations or the law".[1] While there is no global unified law of property-ownership,[3] the informal occupant or community will typically lack security of tenure and, with this, ready or reliable access to civic amenities (potable water, electricity and gas supply, road creation and maintenance, emergency services, sanitation and waste collection). Due to the informal nature of occupancy, the state will typically be unable to extract rent or land taxes.

The term "informal housing" is useful in capturing the informal population other than those living in slum settlements or shanty towns. UN-Habitat more narrowly defines slum housing as lacking at least one of the following criteria: durability, sufficient living space, safe and accessible water, adequate sanitation, and security of tenure.[4]

Common categories or terms associated with informal housing include: slums, shanty towns, squats, homelessness, backyard housing and pavement dwellers.

In developing countries

People around the world face issues of homelessness and insecurity of tenure. However, particularly pernicious circumstances may obtain in developing countries, leading to a large proportion of the population resorting to informal housing. According to Saskia Sassen, in the race to become a "global city" with the requisite state-of-the-art economic and regulatory platforms for handling the operations of international firms and markets, radical physical interventions in the fabric of the city are often called for, displacing "modest, low-profit firms and households".[5] Persistent conflict and insecurity can also weaken the institutions that would record and formalize housing transactions. For instance, until 1991 municipal officials possessed a registry of land in Mogadishu, Somalia. But these records are now held by a diasporic Somali living in Sweden, who charges a fee to verify land deeds.[6]

If households lack the economic resilience to repurchase in the same area or to relocate to a place that offers similar economic opportunity, they are prime candidates for informal housing. For example, in Mumbai, India, fast-paced economic growth, coupled with inadequate infrastructure, endemic corruption and the legacy of restrictive tenancy laws[7] have left the city unable to house the estimated 54% who now live informally.[8] Informal housing is often built incrementally, as householders acquire the resources, time and security to build additions and enhancements.[9]

Many cities in the developing world are experiencing a rapid increase in informal housing, driven by mass migration to cities in search of employment or fleeing from war or environmental disaster. According to Robert Neuwirth, there are over 1 billion (one in seven) squatters worldwide. If current trends continue, this will increase to 2 billion by 2030 (one in four), and 3 billion by 2050 (one in three).[10] In African cities, between half and three-quarters of new housing is developed on informally acquired land.[11] Informal homes, and the often informal livelihoods that accompany them, are set to be defining features of the cities of the future.[12]

See also

References

- 1 2 Roy, Ananya (2009). "Why India Cannot Plan Its Cities". Planning Theory. 8 (1): 80. doi:10.1177/1473095208099299. S2CID 145580709.

- ↑ "The Informal Economy: Fact Finding Study" (PDF). Department for Infrastructure and Economic Cooperation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ Fernandes, Edesio; Varley, Ann (1998). Illegal Cities: Law and Urban Change in Developing Countries. London: Zed Books. p. 4.

- ↑ "Slums: Some Definitions" (PDF). UN-Habitat. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2013.

- ↑ Sassen, Saskia (2009). "The Global City – Strategic Site/New Frontier" in Dharavi: Documenting Informalities. Delhi: Academic Foundation. p. 20.

- ↑ Bonnet, Charlotte; Bryld, Erik; Kamau, Christine; Mohamud, Mohamed; Farah, Fathia (2020-07-28). "Inclusive shelter provision in Mogadishu". Environment and Urbanization. 32 (2): 447–462. doi:10.1177/0956247820942086. ISSN 0956-2478.

- ↑ "Pro-tenant laws in India often inhibit rental market". Global Property Law Guide. 20 June 2006. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ↑ National Building Organisation (2011). Slums in India: A Statistical Compendium. Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation (Government of India).

- ↑ Van Noorloos, Femke; Cirolia, Liza Rose; Friendly, Abigail; Jukur, Smruti; Schramm, Sophie; Steel, Griet; Valenzuela, Lucía (2020-04-01). "Incremental housing as a node for intersecting flows of city-making: rethinking the housing shortage in the global South". Environment and Urbanization. 32 (1): 37–54. doi:10.1177/0956247819887679. ISSN 0956-2478. S2CID 214400055.

- ↑ Neuwirth, Robert. "Our Shadow Cities". TEDTalks. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ Andreasen, Manja Hoppe; McGranahan, Gordon; Kyessi, Alphonce; Kombe, Wilbard (2020-04-01). "Informal land investments and wealth accumulation in the context of regularization: case studies from Dar es Salaam and Mwanza". Environment and Urbanization. 32 (1): 89–108. doi:10.1177/0956247819896265. ISSN 0956-2478. S2CID 213964432.

- ↑ Laquian, Aprodicio A. Basic housing: policies for urban sites, services, and shelter in developing countries (Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 1983).