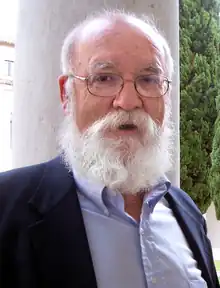

An intuition pump is a type of thought experiment that leads the audience to a specific conclusion through intuition. Daniel Dennett, who coined the term, also called them "persuasion machines."[1]

In Dennett's work

The term was coined by Daniel Dennett.[2] In Consciousness Explained, he uses the term to describe John Searle's Chinese room thought experiment, characterizing it as designed to elicit intuitive but incorrect answers by formulating the description in such a way that important implications of the experiment would be difficult to imagine and tend to be ignored.

In the case of the Chinese room argument, Dennett considers the intuitive notion that a person manipulating symbols seems inadequate to constitute any form of consciousness, and says that this notion ignores the requirements of memory, recall, emotion, world knowledge, and rationality that the system would actually need to pass such a test. "Searle does not deny that programs can have all this structure, of course", Dennett says.[3] "He simply discourages us from attending to it. But if we are to do a good job imagining the case, we are not only entitled but obliged to imagine that the program Searle is hand-simulating has all this structure—and more, if only we can imagine it. But then it is no longer obvious, I trust, that there is no genuine understanding of the joke going on."[4]

Searle responded that Dennett fundamentally did not understand the concept of the Chinese room, and that it was intended to illustrate a semantic point. The point illustrated by the Chinese room was not that the system did not constitute any form of consciousness, according to Searle, but that "[the man in the Chinese room] does not understand Chinese at all, because the syntax of the program is not sufficient for the understanding of the semantics of a language, whether conscious or unconscious."[5]

In his 1984 book Elbow Room, Dennett used the term in a positive sense to describe thought experiments which facilitate the understanding of or reasoning about complex subjects by harnessing intuition:[6]

A popular strategy in philosophy is to construct a certain sort of thought experiment I call an intuition pump. ... Intuition pumps are cunningly designed to focus the reader's attention on "the important" features, and to deflect the reader from bogging down in hard-to-follow details. There is nothing wrong with this in principle. Indeed one of philosophy's highest callings is finding ways of helping people see the forest and not just the trees. But intuition pumps are often abused, though seldom deliberately.

In other scholarship

Dorbolo defines intuition pumps as thought experiments designed to "transform" thinking in their audience, as opposed simply to posing a philosophical problem.[7] The distinction between intuition pumps and thought experiments in general is not entirely clear, however; some writers use the two terms synonymously.[8] Brendel goes further, distinguishing "bad" intuition pumps that discourage considered reflection from "legitimate" thought experiments permissible in philosophical argument.[9] Dowe suggests that intuition pumps constitute a middle ground between Moorean facts, or propositions that are so obviously true that they refute arguments to the contrary; and conceptual analysis.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel. "Daniel Dennett: An Introduction to Intuition Pumps". BigThink.com.

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel (1980). "The Milk of Human Intentionality". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 3 (3): 429. doi:10.1017/s0140525x0000580x. ISSN 1469-1825. S2CID 144583974.

Searle's form of argument is a familiar one to philosophers: he has constructed what one might call an intuition pump, a device for provoking a family of intuitions by producing variations on a basic thought experiment. An intuition pump is not, typically, an engine of discovery, but a persuader or pedagogical tool—a way of getting people to see things your way once you've seen the truth, as Searle thinks he has. I would be the last to disparage the use of intuition pumps—I love to use them myself—but they can be abused. In this instance I think Searle relies almost entirely on ill-gotten gains: favorable intuitions generated by misleadingly presented thought experiments.

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel (1991). Consciousness Explained. Allen Lane: The Penguin Press. p. 438.

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel (1991). Consciousness Explained. The Penguin Press. p. 438.

- ↑ "'The Mystery of Consciousness': An Exchange". The New York Review. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel Clement (1984). Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-585-36508-4. OCLC 47010245.

- ↑ Dorbolo 2011, p. 1644.

- ↑ Dorbolo 2011, p. 1646.

- ↑ Brendel 2005, p. 90.

- ↑ Dowe, Phil (2010). "Proportionality and Omissions". Analysis. 70 (3): 447. doi:10.1093/analys/anq033. ISSN 0003-2638. JSTOR 40930216.

Sources

- Brendel, Elke (23 June 2005). "Intuition Pumps and the Proper Use of Thought Experiments". Dialectica. 58 (1): 89–108. doi:10.1111/j.1746-8361.2004.tb00293.x.

- Dorbolo, Jon Louis (5 October 2011). "Intuition Pumps and Augmentation of Learning". In Seel, Norbert M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 1644–1647. ISBN 978-1-4419-1427-9.

External links

- Dennett, Daniel C. (2013). Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393082067.

- Dennett, D. C., "Intuition Pumps", pp. 180–197 in Brockman, J., The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution, Simon & Schuster, (New York), 1995. Archived 12 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Computer Models as "Intuition Pumps"

- "'The Mystery of Consciousness': An Exchange". The New York Review. Retrieved 25 May 2021.