| Iron Quadrangle | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Paleoproterozoic ~ | |

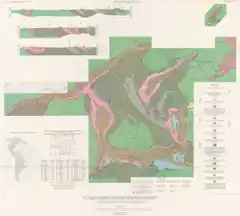

Geologic map of the Iron Quadrangle | |

| Type | Mining district |

| Unit of | Minas Supergroup |

| Underlies | Itacolomi Group |

| Overlies | Rio das Velhas Supergroup |

| Area | 7,000 square kilometres (2,700 sq mi) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Pegmatite, granitoid |

| Other | Itabirite |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 19°54′S 43°12′W / 19.9°S 43.2°W |

| Region | Minas Gerais |

| Country | Brazil |

| Extent | São Francisco craton |

Iron Quadrangle (Brazil) | |

The Iron Quadrangle (Portuguese: Quadrilátero Ferrífero) is a mineral-rich region covering about 7,000 square kilometres (2,700 sq mi) in the central-southern part of the Brazilian state Minas Gerais. The area is known for its extensive deposits of gold, diamonds, and iron ore, being the source of approximately 40% of all gold produced in Brazil between the years 1500 and 2000. The deposits themselves pertain to the Minas Supergroup, a sequence of meta-sedimentary rocks initially formed in the Paleoproterozoic, about 2.5 Ga. In the 2010s, there have been two collapses of large tailings dams, which caused extensive damage and loss of life.

Demographics

The Iron Quadrangle is located in the south-central portion of the state of Minas Gerais and is home to more than 4 million people.[1] The largest city in the region, Belo Horizonte, acts as the regional economic hub and processes most of the gem and mineral wealth produced by the region. Other large settlements include Santa Luzia, Ibirité, and Itabira. The local economy is dependent on mining and associated activities (steel production and metallurgy), tourism and agriculture.

History

The mineral wealth of the Iron Quadrangle has been known since the year 1690. European discovery of gold was followed shortly by discovery of diamonds. The Portuguese Empire exerted strong control over the mining operations, collecting 20% of all production in taxes. During the larger Brazilian Gold Rush of the late 17th to late 19th century, hundreds of thousands of Europeans migrated to the region from both Europe and Northern Brazil, and at least half a million slaves were imported from Africa to work in the mines and lavras.[2] This concentration of wealth and population shifted the economic and political focus of Portuguese Brazil away from the sugar plantations of the north of the country. After gold production slowed in the late 18th century, the economic focus redirected to production of iron ore and agriculture, especially coffee and dairy.

Geology

The iron ore deposits of the Iron Quadrangle are hosted within the Cauê Formation, part of the Minas Supergroup. The Minas Supergroup was initially deposited approximately 2.5 Ga ago on the edge of the São Francisco craton, the geologic core of southern Brazil. The larger Iron Quadrangle contains the following five lithostratigraphic units:[3]

- Archean Basement rock (3.2–2.61 Ga): Gneiss and migmatites of the São Francisco craton. At the time, this craton would have been connected to the Congo craton and would not have been associated with the rest of South America. Also included in this unit are calc-alkaline and granitic plutons emplaced during the Late Archean.

- Rio das Velhas Supergroup (2.86–2.6 Ga): Greenstone and intercalated sedimentary rocks, including Algoman-type banded iron formations (BIF)

- Minas Supergroup (2.6–2.12): Metamorphosed sedimentary units deposited on the shelf of the São Francisco craton. The lowermost units (Tamanduã and Caraça Groups) show a typical marine regression sequence, with conglomerates and sandstones fining upward into marine pelites. These are overlain by the Cauê Formation, Lake Superior-type banded iron formations which are in turn overlain by carbonates of the Gandarela Formation and shallow water to deltaic sediments of the Piracicaba Group. Lastly, the whole sequence is unconformably overlain by the Sabará Group, a mix of turbidites, volcaniclastics, conglomerates and diamictites.

- Post-Minas intrusives (various ages): Pegmatitic dikes and granitoid plutons which intruded into the Minas Supergroup. It is these pegmatites which host the gemstones being mined in the region.

- Itacolomi Group (2.1 Ga): coarse sandstone and conglomerates which overlie the Minas Supergroup. This unit contains banded iron formation clasts which might be derived from the Cauê Formation.

The area shows evidence for a collisional event (the Transamazonian Orogeny) approximately from 2.2 to 1.8 Ga, based on mapped folds and thrust faults. It has been suggested that this event relates to other contemporaneous orogenies around the world, leading to the assemblage of the Supercontinent Columbia.[4][5]

The iron ore in the region is of the type known as itabirite. Itabirite is a metamorphosed variant of banded iron formation in which the original bands of quartz and jasper have been recrystallized to macroscopically distinguishable quartz grains. The iron minerals (hematite and magnetite) are typically present in thin bands.[6] This material typically produces a high-grade iron ore, as impurities such as sulfur or phosphate were removed during the metamorphic processes.

IUGS geological heritage site

In respect of the importance of this record of banded ironstone formations and the ferruginous caves which it hosts, the 'Paleoproterozoic Banded Iron Formations of the Quadrilátero Ferrífero' was included by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) in its assemblage of 100 'geological heritage sites' around the world in a listing published in October 2022. The organisation defines an 'IUGS Geological Heritage Site' as 'a key place with geological elements and/or processes of international scientific relevance, used as a reference, and/or with a substantial contribution to the development of geological sciences through history.'[7]

Mining disasters

There have been 2 major mining disasters in the Iron Quadrangle in the 2010s. In both cases, tailings dams at mines operated in part by Vale S.A. collapsed, leading to flooding and destruction of the downstream areas, as well as severe environmental contamination. On November 5, 2015, the Fundão dam (part of the Germano mining complex) in the Mariana region collapsed, causing 19 fatalities and the destruction of around 200 homes. On January 25, 2019, Dam I at the Córrego do Feijão iron mine collapsed, causing the deaths of 165 people,[note 1] and extensive damage to nearby agricultural lands, bridges and the city of Brumadinho. Between the two events, approximately 72,000,000 cubic metres (2.5×109 cu ft) of mining waste was released to the environment, with much of that waste being washed into nearby major rivers. After the collapse of the Fundão dam, contamination of the Rio Doce caused water shortages for people living downstream.

In response to the 2019 disaster, Vale S.A. halted operations at other nearby mines and has reconfirmed their commitment to decommissioning all upstream tailings dams within the next three years. Vale SA has also been fined R$ 250 million by the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources. Brazilian Authorities have also frozen Vale assets worth R$11.8 billion to ensure funding for recovery efforts.[8]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ as of February 12, 2019

References

- ↑ "IGBE 2010 Census". Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ↑ "E os bandeirantes descobrem o ouro (And the bandeirantes discover the gold)". Brazilian Association of Metals. Archived from the original on 2014-01-09.

- ↑ Alkmim & Marshak, 1998

- ↑ Zhao et al., 2004

- ↑ Zhao et al., 2002

- ↑ "Iron Quadrangle, Minas Gerais, Brazil". Mindat.org. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ↑ "The First 100 IUGS Geological Heritage Sites" (PDF). IUGS International Commission on Geoheritage. IUGS. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ↑ "Vale updates on latest information about Brumadinho". Retrieved 10 February 2019.

Bibliography

- Alkmim, F.F., and S Marshak. 1998. Transamazonian Orogeny in the Southern Sao Francisco Craton Region, Minas Gerais, Brazil: evidence for Paleoproterozoic collision and collapse in the Quadrilatero Ferrifero. Precambrian Research 90(1–2). 29–58. Accessed 2019-02-20.

- Cabral, Alexandre Raphael; Zeh, Armin; Koglin, Nikola; Seabra Gomes, Antônio Augusto; Viana, Deiwys José; Lehmann, Bernd (2012-05-01). "Dating the Itabira iron formation, Quadrilátero Ferrífero of Minas Gerais, Brazil, at 2.65Ga: Depositional U–Pb age of zircon from a metavolcanic layer". Precambrian Research. 204–205: 40–45. Bibcode:2012PreR..204...40C. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2012.02.006. ISSN 0301-9268.

- Zhao, G.; M. Sun; S.A. Wilde, and S. Li. 2004. A Paleo-Mesoproterozoic supercontinent: assembly, growth and breakup. Earth-Science Reviews 67(1–2). 91–123. Accessed 2019-02-20.

- Zhao, G.; P.A. Cawood; S.A. Wilde, and M. Sun. 2002. Review of global 2.1 – 1.8 Ga orogens: implications for a pre-Rodinia supercontinent. Earth-Science Reviews 59(1–4). 125–162. Accessed 2019-02-20.