Isaac B. Desha | |

|---|---|

| Born | Isaac Bledsoe Desha January 1, 1802 |

| Died | August 13, 1828 (aged 26) |

| Other names | John Parker |

| Occupation | Tanner |

| Criminal status | Died in incarceration |

| Spouse | Cornelia Pickett |

| Children | 1 child |

| Parent(s) | Joseph and Margaret Bledsoe Desha |

| Motive | Robbery |

| Conviction(s) | Murder (January 31, 1825; new trial granted) Murder (February 1826; overturned) |

| Criminal charge | Murder |

| Penalty | Execution by hanging (pardoned) |

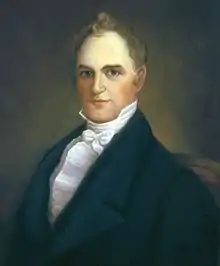

Isaac Bledsoe Desha (January 1, 1802 – August 13, 1828) was a 19th-century American tanner who was convicted of murdering one man in Kentucky, and confessed to murdering another in Texas. He was notable as the son of the Kentucky Governor, Joseph Desha. Shortly after his father's election as governor in 1824, Desha was accused of robbing and killing a man named Francis Baker, who was passing through Kentucky. Circumstantial evidence implicated Desha, who denied the crime.

Given the heated political environment of the Old Court-New Court controversy, allies of his father claimed that the governor's political enemies had framed his son. The governor's legislative allies passed legislation providing for a favorable change of venue for the trial, and the governor used his appointment power to ensure that sympathetic judges would hear the case. Isaac Desha was twice convicted, but both times, the judge in the case set aside the verdict on procedural grounds. While awaiting a third trial, Desha attempted suicide by slitting his throat, but doctors saved his life, reconnecting his severed windpipe with a silver tube. Shortly after the suicide attempt, Governor Desha issued a pardon for his son.

Isaac Desha left Kentucky and assumed an alias. He went to New Orleans. From there, he traveled with a man named Thomas Early to San Antonio, Texas. When Early went missing during their travels, Desha fell under suspicion. A former Kentuckian living in Texas recognized Desha. Arrested soon after Early's body was found, Desha confessed to the murder after being recognized by a second man from Kentucky. A day before his trial was to start, Desha died of a fever. A legend soon arose that he had faked his death and fled to Hawaii, where he married a native woman and fathered several children. Later historians have debunked that myth.

Early life and education

Isaac Bledsoe Desha was born January 1, 1802; he was one of thirteen children of Margaret (Bledsoe) and Joseph Desha.[1] He was named for his maternal grandfather.[2] Educated mostly in the local (Maysville, Kentucky) schools, for a time Isaac attended a school run by Mr. Bailey and boarded with Bailey's father.[3] In October 1817, he was apprenticed to Archibald Logan, a tanner.[3] He lived and studied with Logan until May 1821.[3]

Marriage and family

In November 1823, the young man married Cornelia Pickett.[3] Desha's sister Ellen had previously married Pickett's brother James.[3]

Political environment

Desha's father Joseph was elected as governor of Kentucky in August 1824.[2] The primary issue in the campaign was relief for the state's large debtor class, still reeling from the Panic of 1819.[4] The state's voters split between those supporting laws favorable to debtors – called the Relief Party – and those supporting laws that protected creditors – called the Anti-Relief Party.[4] Shortly before Desha's election, the Kentucky Court of Appeals had struck down some legislation as unconstitutional that had been passed by the Relief Party, then a majority in the Assembly.[5]

After Desha was elected, Relief legislators, who held majorities in both houses of the General Assembly, attempted to remove the offending judges from office.[6] Failing to achieve the needed two-thirds majority, the legislature passed a reorganization act abolishing the Court of Appeals and replacing it with a new court. Desha appointed justices favoring relief.[7] The original court continued to claim authority as the court of last resort in the state; during what became known as the Old Court-New Court controversy, both courts operated simultaneously, with both claiming legitimacy.[8] It was a politically tumultuous time.

Murder of Francis Baker

On the night of November 1, 1824, Desha attended a celebration at a neighbor's house.[3] He later stayed the night at Doggate's Tavern in Fairview, just over the county line in Fleming County.[9] The next morning, he ate breakfast at the tavern,[10] joined by eight other men, including Francis Baker. Editor of the Mississippian newspaper in Natchez, Baker was returning to his hometown of Trenton, New Jersey to marry a young woman there.[9] Over breakfast, Baker mentioned wanting to visit a friend, Captain John Bickley, who lived in the area.[10] Desha remarked that he knew where Bickley lived and, intending to ride in that direction, asked if Baker wanted to join him.[10] Baker accepted, and the two men left about 8 a.m. toward Maysville. Desha rode his bay mare and Baker his gray mare, a fine horse that had already attracted much attention during his travel through Kentucky.[11]

About 10 a.m., one of Desha's neighbors encountered the riderless gray mare, still rigged with saddle and bridle.[10] Catching the horse, he rode it up the road, shortly finding Desha's riderless bay (which he recognized), with a saddle but no bridle.[10] He noticed blood on the neck and withers of Desha's horse.[10] Further along, the neighbor encountered Desha on foot, carrying two saddlebags.[10] Desha said that he had just accepted the gray mare as payment from a man who owed him money.[10] He did not volunteer how the two horses had escaped his control, but mounted the gray mare and returned home.[9] Later that day, friends at Desha's tannery noticed that he was unusually quiet and repeatedly asked what was wrong.[12] He said that he had been kicked by a horse and severely cut his finger in separate incidents the previous day.[12]

His unusual behavior continued to the point that Desha's pregnant wife Cornelia moved out of the house and refused to return.[12] She later gave birth to their daughter and only child, who she named after her mother. She never returned to Desha.

Over the next few days, neighbors began to discover items along the route Desha and Baker had taken from Doggate's Tavern to Maysville.[12] These included a bloody glove, a pair of saddlebags with the bottoms cut out, and Desha's missing horse bridle.[12] On November 8, three men discovered a man's body – its upper half covered by a log – about 50 yards (46 m) off the road on the Fleming County side.[12] The men did not move the body, but reported it to local authorities, who returned to recover it.[12] The victim had four or five bludgeon wounds to the head, stab wounds in the chest and shoulder, and his throat had been slit, severing his windpipe.[13] The man wore a shirt, waistcoat, socks, and a single glove; a search of the area yielded pantaloons and a coat.[13] Authorities brought the body to town, where Captain John Bickley (whom Baker had been riding to visit) identified it as Francis Baker.[13]

Investigators examined the body for several days before burying it on November 11 in a local church cemetery.[13] Returning to search the area again, authorities found several changes of clothes and other accoutrements, all with marks identifying the owner cut out.[14] Also located were several pieces of paper – one with the name "Baker" written on it – a hat, a pocketbook similar to the one Desha was known to carry, and lead and a cap from a riding whip, which Desha was also known to use.[14]

Arrest and trials

With evidence strongly pointing to Desha as the murderer, General William Reed summoned Desha to his house on November 9 and ordered him to remain until an examining trial could be held.[14] Desha complied, showed no emotion when viewing Baker's body, and did not attempt to flee although left unguarded in the house.[14] The examining trial resulted in Desha's formal arrest, and he was imprisoned in Flemingsburg, Kentucky.[15] Relief Party partisans said that Desha was innocent and his arrest was fabricated by the Anti-Relief Party to embarrass his father Governor Desha and weaken him politically.[5]

On November 24, State Representative John Rowan – a Relief partisan – introduced legislation in the Kentucky General Assembly ordering the Fleming Circuit Court to convene a special session in December for Desha's trial; it provided that, at the trial, Desha would be given the option of a change of venue from Fleming County, where he lived and the murder was committed, to Harrison County, where his father lived.[16] Governor Desha appeared before the committee reviewing the bill to advocate its passage.[16] The bill was reported favorably by the committee, passed by both houses of the General Assembly, and signed by the governor on December 4, 1824.[16] On December 20, 1824, the Fleming Circuit Court returned an indictment against Desha for the murder of Francis Baker.[15] At that time, Desha requested the change of venue.[16]

Judge John Trimble, the circuit court judge in Harrison County who would have presided over the case, was appointed before the trial by Governor Desha to a seat on the "New" Court of Appeals authorized by the Assembly.[17] Trimble personally selected Judge George Shannon of Lexington to preside in his stead.[17]

Desha's trial began January 17, 1825, in Cynthiana.[15] William K. Wall, Commonwealth's Attorney for Harrison County, was the prosecutor, assisted by Fleming County Commonwealth's Attorney (and future Congressman) John Chambers and Martin P. Marshall.[18] Rowan, who had just been elected to the U.S. Senate, was Desha's primary defense counsel, assisted by the governor's Secretary of State (and later U.S. Senator) William T. Barry, former Congressman William Brown, T. P. Taul, and James Crawford.[15][19] It took two days to empanel a jury.[18] Witness testimony consumed the next week, and Governor Desha attended each day of the trial.[20] The closing statements of Rowan and Barry, both known as outstanding orators, took several days, and Chambers spoke last.[21]

The defense maintained that the evidence against Desha was largely circumstantial.[22] They said that Desha's personal items could easily have been planted where they were found.[22] They pointed out that, despite the stab wounds on Baker's body, no blood was found on the ground near the road or on the path along which the murderer had dragged the body to conceal it.[22] Finally, they contended that, although the days had been unusually warm and wild boars were known to inhabit the area, Baker's body showed no obvious signs of decomposition or disturbance by animals, as might have been expected had it been there for six days, as the prosecution had charged.[22]

On January 31, 1825, Desha was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging.[23][24] The next day, Rowan filed a motion for a new trial, citing jury tampering, and Judge Shannon sustained Rowan's motion.[23] Throughout the court's March and June terms, a jury was unable to be empaneled due to the extreme publicity the case received.[25]

During the September term, a jury was finally selected, and the trial consumed the rest of the term.[25] Much of the same evidence was presented, and the second jury also voted for a guilty verdict.[22] The date for Desha's execution was set for July 14, 1826.[22] Harry O. Brown, the judge in the case, had been temporarily appointed by Governor Desha to fill a vacancy.[6] He set aside the verdict, ruling that the prosecution had failed to prove that the murder occurred in Fleming County, as charged in the indictment.[26] The prosecution unsuccessfully argued that because a change of venue had already been granted, the place of the murder was immaterial.[6]

The process of selecting a third jury consumed a year and a half.[26] During the delay, Desha attempted suicide by cutting his throat and severed his windpipe.[22] Doctors used a silver tube to repair his windpipe, and Desha survived.[6] On the last day of the court's term in June 1827, the judge announced another continuance, since the court had not yet empaneled a jury.[27] Governor Desha stood and produced a pardon for his son.[27] Although legend holds that Governor Desha resigned immediately after issuing the pardon, records show that he served out the rest of his term.[22] The pardon damaged the governor's reputation and that of the Relief Party, which lost a number of legislative seats in the subsequent elections.[6]

Departure of Isaac Desha

Freed, Desha left Kentucky, traveling down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.[22] According to legend, he attempted to rob a flatboat skipper near Vicksburg, Mississippi.[28] It happened the skipper was a longtime acquaintance of Desha, named G. W. Crawford.[28] Crawford recognized Desha and asked why he would try to rob him.[28] Desha confessed that he had been living as an outlaw since his father's pardon.[28] Crawford urged Desha to abandon his illegal activities and offered to give him free passage to New Orleans, Louisiana.[28] Desha accepted, telling Crawford that he planned to travel on to a distant place, assume a new name, and seek a fresh start.[28]

In New Orleans, Desha assumed the name John Parker.[28] Meeting an Ohio native named Thomas Early, he learned the man was carrying a substantial amount of money and was on his way to Texas to purchase some horses and mules.[29] Desha joined Early, traveling with him on a schooner dubbed the Rights of Man across the Gulf of Mexico into Galveston Bay.[28][29] In April 1828, Desha and Early disembarked at Rightors Point (now Morgan's Point, Texas), and from there, they traveled to San Felipe de Austin, arriving in early May.[28] After a brief stay, the two set out on horseback toward San Antonio. By the time Desha reached Gonzales, he was traveling alone.[29]

Desha continued on to San Antonio, where he lost a substantial amount of money playing Monte Bank.[28] He decided to return to San Felipe.[29] Meeting two Americans and a Mexican cigar maker travelling that way, with their permission, he traveled with them.[29] After his return to San Felipe, the citizens began to suspect Desha of murdering Early.[29] A few days after Desha's arrival, Early's clothing was found in a nearby creek. Scattered nearby, a search party located skeletal remains believed to be Early's.[30]

Thomas Duke Marshall, a nephew of Chief Justice John Marshall and former resident of Washington County, Kentucky, was living in San Felipe. He noticed that the man called John Parker bore a strong resemblance to the Desha family of Kentucky and that he breathed through a silver tube like the one used by Isaac Desha.[30] Marshall arrested Desha. After another former Kentuckian in the area also said he believed the suspect was Isaac Desha, Desha admitted his identity and confessed to murdering Early.[30] He said he had intended to rob the Americans who had traveled with him from San Antonio, but the Mexican had watched him too closely.[29] Although there was no jail in the town, a local blacksmith was commissioned to construct irons to restrain Desha until his trial.[30]

Death and legend of escape to Hawaii

Desha's trial for Early's murder was set for August 14, 1828, but he died of a fever the day before the trial was to start.[29] He was buried in San Felipe de Austin.[29]

After his death, a legend arose that he had not died, that his funeral was staged, and that he had escaped to Hawaii, married a native woman, and fathered several children with her.[31] Andrew Forest Muir, writing in 1956 in the Filson Club History Quarterly, debunked this legend. He documented that the first Deshas in Hawaii did not arrive until nearly two decades after Isaac Desha's death. At the time of Baker's murder, the progenitor of the Hawaiian Desha family had been four years old.[32] That progenitor was John R. Langherne Desha, a grandson of Governor Joseph Desha and nephew of Isaac Desha. In Honolulu, he helped establish Queen's Hospital and worked there until his death.[32]

References

- ↑ Cisco, p. 171

- 1 2 McCarthey, p. 293

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McCarthey, p. 294

- 1 2 Johnson, p. 34

- 1 2 Johnson, p. 35

- 1 2 3 4 5 Theis, "Murder and Inflation: the Kentucky Tragedy"

- ↑ Stickles, p. 60

- ↑ Harrison and Klotter, p. 111

- 1 2 3 McCarthey, p. 295

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 McCarthey, p. 296

- ↑ McCarthey, pp. 295–296

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 McCarthey, p. 297

- 1 2 3 4 McCarthey, p. 298

- 1 2 3 4 McCarthey, p. 299

- 1 2 3 4 McCarthey, p. 300

- 1 2 3 4 Johnson, p. 38

- 1 2 Johnson, p. 39

- 1 2 Parish, p. 50

- ↑ Parish, p. 49

- ↑ Parish, p. 52

- ↑ Parish, p. 56

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 McCarthey, p. 302

- 1 2 McCarthey, p. 301

- ↑ Clark and Lane, p. 22

- 1 2 Parish, p. 61

- 1 2 Parish, p. 62

- 1 2 Parish, p. 63

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Muir, p. 320

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 McCarthey, p. 303

- 1 2 3 4 Muir, p. 321

- ↑ Muir, p. 319

- 1 2 Muir, p. 322

Bibliography

- Cisco, Jay Guy (1909). Historic Sumner County, Tennessee: With Genealogies of the Bledsoe, Cage and Douglass Families and Genealogical Notes of Other Sumner County Families. Folk-Keelin printing company. ISBN 0806351276.

- Clark, Thomas D.; Margaret A. Lane (2002). The People's House: Governor's Mansions of Kentucky. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2253-8.

- Harrison, Lowell H.; James C. Klotter (1997). A New History of Kentucky. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2008-X.

- Johnson, Lewis Franklin (1916). "The Assassination of Francis Baker by Isaac B. Desha, in 1824". Famous Kentucky Tragedies and Trials: A Collection of Important and Interesting Tragedies and Criminal Trials which Have Taken Place in Kentucky. Baldwin Law Book Company, Incorporated.

- McCarthy, Jeanette (October 1962). "The Strange Case of Isaac B. Desha". Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 60 (4).

- Muir, Andrew Forest (October 1956). "Isaac Desha, Fact and Fancy". Filson Club History Quarterly. 30 (4).

- Parish, John Carl (1909). John Chambers. State Historical Society of Iowa. Archived from the original on 2005-03-08. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- Stickles, Arndt M. (1929). The Critical Court Struggle in Kentucky, 1819–1829. Indiana University.

Further reading

- Bruce, Dickson D. (2006). The Kentucky Tragedy: A Story of Conflict and Change in Antebellum America. Louisiana State University Press.

- Thies, Clifford F. (2007-02-07). "Murder and Inflation: the Kentucky Tragedy, Review of 'The Kentucky Tragedy' by Dickson Bruce". Ludwig von Mises Institute.