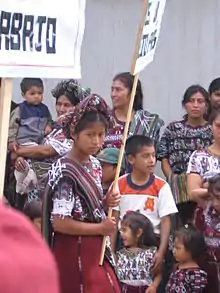

Ixil people at a festival in Nebaj, Guatemala. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 133,329[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| (Campeche, Quintana Roo) | |

| (Santa Maria Nebaj) | |

| Languages | |

| Ixil, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Catholic, Evangelical, Maya religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Awakatek | |

The Ixil (pronounced [iʂil]) are a Maya people located in the states of Campeche and Quintana Roo in Mexico and in the municipalities of Santa Maria Nebaj, San Gaspar Chajul, and San Juan Cotzal in the northern part of the Cuchumatanes mountains of the department of Quiché, Guatemala. These three municipalities are known as the Ixil Triangle and are the place of origin of the Ixil culture and where the majority of the population lives.

During the Guatemalan Civil War in the decade of 1980, the Ixil people was victim and target of a military repression and violence by the army and government of Guatemala; due to this military campaign against the Ixil people, they were forced to migrate to Mexico to survive. Once in Mexican territory, they established refugee camps that later turned to new towns and permanent communities.[2]

Language

The Ixil language belongs to the Mamean branch of Mayan languages and has two dialects: Ixil Nebajeño and Ixil Chajuleño. It is very closely related to the Awakatek language.[3]

Location

In Campeche, the Ixil live in the communities of Quetzal Edzná and Los Laureles from the Campeche municipality and in Maya Tecún II from the municipality of Champotón. In Quintana Roo they live in the localities of Kuchumatán and Maya Balam from the Bacalar municipality.[4]

Genocide in Guatemala

In the early 1980s, the Ixil Community was one of the principal targets of a genocide operation, involving systematic rape, forced displacements and hunger during the Guatemalan civil war. In May 2013 Efraín Ríos Montt was found guilty by a Guatemala court of having ordered the deaths of 1,771 Ixil people. The presiding judge, Jazmin Barrios, declared that "[t]he Ixils were considered public enemies of the state and were also victims of racism, considered an inferior race."[5] According to a 1999 United Nations truth commission, between 70% and 90% of Ixil villages were razed and 60% of the population in the altiplano region were forced to flee to the mountains between 1982 and 1983. By 1996, it was estimated that some 7,000 Maya Ixil had been killed.[6] The violence was particularly heightened during 1979–1985 as successive Guatemalan administrations and the military pursued an indiscriminate scorched-earth (in Spanish: tierra arrasada) policy.[7]

In 2013, General Efraín Ríos Montt, who served as President of Guatemala from 1982 to 1983, was found guilty of genocide against the Ixil people.[8]

Celebrations

In Campeche, the Ixil celebrate the Day of the Nature with a ceremony to thank Mother Earth for the food granted to them. This ceremony starts near a body of water where the people come together to share cultivated products like corn, beans, fruits and vegetables.[9]

Religion

In Campeche, the Ixil people praise the Sun (K'ii in Ixil) in a daily ritual where the head of the family goes right to the sunset, and in ceremonial manner thanks the Sun for its light and for guiding his path to work, asking to not suffer any accident along the way or get lost.[10]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Resultados Censo 2018" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadistica Guatemala. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ↑ "Atlas de los Pueblos Indígenas de México. Ixiles - Historia".

- ↑ "Catálogo de las lenguas indígenas nacionales: Variantes lingüísticas de México con sus autodenominaciones y referencias geoestadísticas. Ixil".

- ↑ "Codice México: Ixil".

- ↑ "Guatemala's Rios-Montt found guilty of genocide". BBC News. 11 May 2013.

- ↑ Myers, Laura (15 May 2013). "View from Chajul: The Rios Montt Genocide Trial". The Globalist. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ See the section "Agudización de la violencia y militarización del Estado (1979-1985)" Archived 2013-05-06 at the Wayback Machine of CEH's report (CEH 1999, ch. 1). In particular, see para. 361, which records of the Guatemalan governments at the time that "...le dio continuidad a la estrategia de tierra arrasada, destruyendo cientos de aldeas, principalmente en el altiplano, y provocando un desplazamiento masivo de la población civil que habitaba las áreas de conflicto."

- ↑ Malkin, Elisabeth (10 May 2013). "Former Leader of Guatemala Is Guilty of Genocide Against Mayan Group". New York Times. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "Atlas de los Pueblos Indígenas de México. Ixiles - Fiestas".

- ↑ "Atlas de los Pueblos Indígenas de México. Ixiles - Religión y cosmovisión".

References

- CEH [Comisión de Esclarecimiento Histórico] (1999). Guatemala, Memoria del silencio = Tz'inil na'tab'al (online reproduction by the Science and Human Rights Program of the AAAS) (in Spanish). Guatemala City: CEH. ISBN 99922-54-00-9. OCLC 47279275. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- Colby, Benjamin N. (January 1976). "The Anomalous Ixil - Bypassed by the Postclassic?". American Antiquity. Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology. 41 (1): 74–80. doi:10.2307/279043. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 279043. OCLC 1479302. S2CID 55074656.

- Colby, Benjamin N.; Lore M. Colby (1981). The Daykeeper: The Life and Discourse of an Ixil Diviner. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-19409-8. OCLC 7197630.

- Colby, Benjamin N.; Pierre L. Van Den Berghe (1969). Ixil Country: A Plural Society in Highland Guatemala. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 23254.