.jpg.webp)

Jacob ben Abraham Zaddiq (Hebrew: יעקב בן אברהם צדיק; also written Zaddik, and known under the Latinized name Jacob Justo) was a Dutch Jewish merchant of Portuguese descent who worked in Amsterdam in the early 17th century.

Biography

Zaddiq was a Portuguese-Jewish banker and merchant[1] whose community moved to Amsterdam following the 1579 Union of Utrecht.[2] He was married to Gracia da Costa (in Hebrew, Rita Zaddiq) both had come from Hamburg to Amsterdam.[3]

Zaddiq is known also for being reported to the Amsterdam authorities as a wife-beater: testimony given in court by a number of witnesses showed he had beaten his wife (apparently he had a history of being violent toward her[3]) with a stick and thrown her down the stairs. He was sentenced to a year in prison.[4]

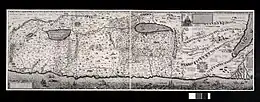

Map of Canaan

Zaddiq is responsible, with engraver Abraham Goos, for the first printed map of the Holy Land in Hebrew, printed in 1620/21.[4] In the framed colophon, in the first line it reads: Hebrew: ציור מצב ארצות כנען, lit. 'A Drawing of the Situation of the Lands of Canaan'

The map was based on the work of Christian Kruik van Adrichem.[5] Zaddiq explains, in the colophon he prepared for the map, how he copied van Adrichem's map and translated its captions into Hebrew, and that he "carefully checked that every detail would be appropriate for his Jewish audience".[6] Zaddiq made some significant changes to the original map. It contained a number of illustrations of Jesus's life at the appropriate places in Canaan, which Zaddiq removed—details such as a miniature illustrating the Exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac and one for the Transfiguration of Jesus on Mount Tabor. On the other hand, he added details appropriate to a Jewish audience, including a number of ships that fly historically important flags: a ship near the Nile delta flies a Muslim flag, signifying the Muslim rule over Egypt, and another off the coast of north Sinai flies the Star of David. According to Rehav Rubin, "This Jewish element perhaps gives voice to the author's desire to visit Eretz Yisrael or his deep yearning for the reestablishment of the Judean kingdom".[1]

In a departure from van Adrichem's map, the upper Hebrew caption on Zaddiq's map recites several Hebrew verses, the first one being a partial quote from Deuteronomy 8:15; the second verse being a partial quote from Deuteronomy 8:2; the third verse being a partial quote taken from Jeremiah 2:6; the fourth verse, where it mentions the "land of the gazelle," is an allusion to Ezekiel 20:6; the fifth verse is a partial quote taken from Exodus 3:8; the sixth verse is taken from Deuteronomy 8:7; the seventh verse from Deuteronomy 8:8; the eighth verse being from Deuteronomy 11:12; which verse, in turn, is followed by Jeremiah 3:19.

The colophon also contains a portrait of Zaddiq, and the text explains the portrait as well as the map. It states that it was engraved by Abraham Goos from Amsterdam. The map was to help Jews become acquainted with the Holy Land that God had given them, and he added the portrait "so that my people will preserve a good keepsake of me". He had himself depicted as a baroque gentleman, a reputable, dignified, and important Spanish courtier—a representation far removed from reality.[7][8]

See also

References

- 1 2 Rubin, Rehav (2018). Portraying the Land: Hebrew Maps of the Land of Israel from Rashi to the Early 20th Century. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 103–12. ISBN 9783110570656.

- ↑ Mercator's World: The Magazine of Maps, Atlases, Globes, and Charts. Aster. 1998. p. 70.

- 1 2 Lieberman, Julia Rebollo (2010). "Childhood and Family among the Western Sephardim in the Seventeenth Century". In Lieberman, Julia Rebollo (ed.). Sephardi Family Life in the Early Modern Diaspora. UPNE. p. 137. ISBN 9781584659433.

- 1 2 Garel, M. (1987). "La première carte de terre sainte en Hébreu (Amsterdam, 1620/21)". Studia Rosenthaliana. 21 (2): 131–39.

- 1 2 Freund, Richard (2014). "The Two Bethsaidas". In Ellens, J. Harold (ed.). Bethsaida in Archaeology, History and Ancient Culture: A Festschrift in Honor of John T. Greene. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 26–46. ISBN 9781443861601.

- ↑ Rubin, Rehav (2010). "A Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Map from Mantua". Imago Mundi. 62 (1): 30–45. doi:10.1080/03085690903319259. JSTOR 20720527. S2CID 161544847.

- ↑ Cohen, Richard I. (1998). "The Visual Image of the Jew". Jewish Icons: Art and Society in Modern Europe. University of California Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9780520205451.

- ↑ Michael Zell (2002). Reframing Rembrandt: Jews and the Christian Image in Seventeenth-century Amsterdam. University of California Press. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-0-520-22741-5. Retrieved 2 May 2013.