James Gibbs | |

|---|---|

James Gibbs, with a ghostly view of his Radcliffe Camera, ca 1750 by Andrea Soldi | |

| Born | 23 December 1682 |

| Died | 5 August 1754 London, England, Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Alma mater | University of Aberdeen |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | The Senate House Radcliffe Camera St Martin-in-the-Fields St Mary le Strand Ditchley House |

James Gibbs (23 December 1682 – 5 August 1754) was one of Britain's most influential architects. Born in Aberdeen, he trained as an architect in Rome, and practised mainly in England. He is an important figure whose work spanned the transition between English Baroque architecture and Georgian architecture heavily influenced by Andrea Palladio. Among his most important works are St Martin-in-the-Fields (at Trafalgar Square), the cylindrical, domed Radcliffe Camera at Oxford University, and the Senate House at Cambridge University.

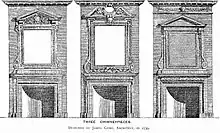

Gibbs very privately was a Roman Catholic and a Tory. Because of this and his age, he had a somewhat removed relation to the Palladian movement which came to dominate English architecture during his career. The Palladians were largely Whigs, led by Lord Burlington and Colen Campbell, a fellow Scot who developed a rivalry with Gibbs. Gibbs' professional Italian training under the Baroque master Carlo Fontana also set him uniquely apart from the Palladian school.[1] However, despite being unfashionable, he gained a number of Tory patrons and clients, and became hugely influential through his published works, which became popular as pattern books for architecture. The naming of the Gibbs surround for doors and windows, which he certainly did not invent, testifies to this influence.

His architectural style did incorporate Palladian elements, as well as forms from Italian Baroque and Inigo Jones (1573–1652), but was most strongly influenced by the work of Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723), who was an early supporter of Gibbs. Overall, Gibbs was an individual who formed his own style independently of current fashions. Architectural historian John Summerson describes his work as the fulfilment of Wren's architectural ideas, which were not fully developed in his own buildings.[2] Despite the influence of his books, Gibbs, as a stylistic outsider, had little effect on the later direction of British architecture, which saw the rise of Neoclassicism shortly after his death.

Biography

Background and education

James Gibbs was born on 23 December 1682 in Fittysmire, Aberdeen,[3] Scotland, a younger son of Patrick Gibbs, merchant, and his second wife Ann (née Gordon). The family was Roman Catholic; there was a half-brother, William, from Patrick's first marriage to Isabel (née Farquhar).[4] Gibbs was educated at Aberdeen Grammar School and Marischal College.[5] After the death of his parents he went in 1700 to stay with relatives in Holland.[5] He later travelled through Europe, visiting Flanders, France, Switzerland and Germany. Some time afterwards he left for Rome, travelling via France. On 12 October 1703 he registered as a student at The Scots College.[6] He would have been studying for the Catholic priesthood but had second thoughts.[6] By the end of 1704 he was studying architecture under Carlo Fontana;[7] he was also taught by Pietro Francesco Garroli, professor of perspective at the Accademia di San Luca.[8] While in Rome Gibbs met John Perceval, 1st Earl of Egmont, who attempted to persuade him to move to Ireland.[8] He moved to London in November 1708;[8] his return was probably due to the terminal illness of his half-brother William, who died before James reached Britain.[9]

Career

Still intending to take up the offer of work in Ireland, he had been befriended by John Erskine, Earl of Mar, while abroad. The Earl persuaded Gibbs to remain in London, offering him his first commission, alterations to his house in Whitehall.[8] Around this time he met Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, who would be a powerful patron and friend (Gibbs would later remodel the Earl's house Wimpole Hall) and James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos (for whom he would be one of the architects to work at Cannons from 1715 to 1719[10]). Gibbs was one of the sixty founder members of Godfrey Kneller's Academy of Painting, founded in 1711.[11] In August 1713 Gibbs discovered that William Dickinson was resigning as architect from the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches; the commissioners included Sir Christopher Wren, Sir John Vanbrugh and Thomas Archer. With the backing of, amongst others, the Earl of Mar and Sir Christopher Wren, Gibbs was appointed architect to the commission on 18 November 1713,[12] where he would have worked with Nicholas Hawksmoor, his fellow architect to the commission. But a combination of events would ensure Gibbs was deprived of his place as architect to the commission by December 1715: Queen Anne had died and a Whig government had replaced the Tories; and the failure of the 1715 Jacobite rising that was supported by the Earl of Mar were all factors.[12] Still he was able to complete one church, St Mary-le-Strand, that he described as "the first publick (sic) building I was employed in after my arrival from Italy; which being situated in a very publick place, the Commissioners... spar'd no cost to beautify".[12] On 18 December 1716 Gibbs joined the "Vandykes clubb" (sic), also called the Club of St Luke for "Virtuosi in London". Fellow architects who were members included William Kent and William Talman; other notable members with whom Gibbs would later work included the garden designer Charles Bridgeman and the sculptor John Michael Rysbrack, who sculpted many of the memorials Gibbs designed.[13] In March 1721 Charles Bridgeman, James Thornhill, John Wootton and Gibbs were all travelling together from London to Wimpole Hall where they were all working for Edward Harley, the Earl of Oxford; Thornhill recalled that they drank Harley's "healths over and over, as well in our civil as bacchanalian hours" and talked "of building, pictures and may be towards the close of politics or religion".[14]

.jpg.webp)

In 1720 Gibbs was invited along with other architects to enter a competition to design a new church to replace the dilapidated church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. He won, and on 24 November 1720 he was appointed architect of the new church,[15] which was to be his most famous building. Horace Walpole described Gibbs as being around 1720 as "the architect most in vogue".[16] In 1720 Gibbs was approached by the Provost of King's College, Cambridge to complete the college. The scheme consisted of three buildings, all 53 feet (16 m) high, forming a courtyard 240 by 282 feet (73 by 86 m) to the south of the Chapel. In the end only the western block, the 236-foot (72 m) long Fellows' Building, was constructed from 1721 to 1724; the eastern Fellows' Building would have been identical, and the southern building would have had a great octastyle Corinthian portico, and been 236 feet (72 m) long, containing the great dining hall, Provost's Lodge and offices.[17] On 11 December 1721 Edward Lany, one of the Syndics of University of Cambridge, thanked Edward Harley Earl of Oxford for sending "Mr Gibbs's design for our building. I design to offer it to the Syndics as soon as they meet...I have not skill enough myself to judge of it".[18] This referred to a design for a new central building for the University to house the library, Senate House, the Consistory and Register Offices. Gibbs produced a second larger design in 1722, consisting of a courtyard building with two projecting wings to the east, 189 by 118 feet (58 by 36 m).[18] Work started on the building in November 1722, but in the end only the Senate House, 110 by 50 feet (34 by 15 m), the northern of the two east wings, was built. It was finished in 1730.

By 1723 Gibbs was rich enough to open an account at Drummonds Bank, with his first year's balance being £1055 11 shillings 4 pence.[19] 1723 also saw Gibbs being made a governor of St Bartholomew's Hospital;[20] other governors included fellow architects Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and George Dance the Elder. On 1 August 1728 it was decided to rebuild the Hospital.[20] Gibbs offered his service for free, and designed a quadrangle of 200 by 160 feet (61 by 49 m) with four near-identical plain blocks. In March 1726 Gibbs was made a member of the Society of Antiquaries of London.[21] and in 1727 he was awarded with the only government post he ever held, Architect of the Ordnance,[21] which he held for life. He was given it thanks to the Duke of Argyll who was Master of the Ordnance and in 1729 he was elected to the Royal Society.[21] One of the most serious disappointments of Gibbs's career was his failure to win the commission for the Mansion House, London. There were two competitions for the building, both of which he entered – the first in 1728 and a second in 1735; in the end George Dance the Elder won the commission.[22] In 1735, Gavin Hamilton painted A Conversation of Virtuosis... at the Kings Arms, a group portrait that included Michael Dahl, George Vertue, John Wootton, Gibbs and Rysbrack, along with other artists who were instrumental in bringing the Rococo style to English design and interiors.[23] After the death in 1736 of Nicholas Hawksmoor, who was architect for the Radcliffe Camera, Gibbs was appointed on 4 March 1737 to replace him.[24] The Radcliffe Camera was finished by 19 May 1749.[25] Gibbs was awarded by Oxford University an honorary degree of Master of Arts in 1749 recognition of the completion of the Radcliffe Camera.[4]

Collections

A list of the nearly 700 books in his library is preserved in the Bodleian Library.[26] While architecture and related crafts made up the bulk of his books, other subjects covered included antiquities, coins, and heraldry; histories of England, Scotland and Rome and other nations; literature including works by Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, Daniel Defoe and Matthew Prior; travel books including Egypt, the South Seas, Russia, Hungary, Lapland, Virginia, Ceylon and Abyssinia; missionary travels including China, Formosa, Guinea, Borneo and the East Indies; books on religion including both Anglican and Roman Catholic works; and even cookery books. The most significant of the architectural works were Vincenzo Scamozzi's L'Idea dell'Architettura Universale, Sebastiano Serlio's Sette Libri d'Architettura, Domenico Fontana's Della transportatione dell'obelisco Vaticano e delle fabriche di Sisto V, Colen Campbell's Vitruvius Britannicus, Giacomo Leoni's The Architecture of A. Palladio, in Four Books, William Kent's The Designs of Inigo Jones and Robert Wood's The ruins of Palmyra. Gibbs is also known to have owned at least 117 paintings, including works by Canaletto, Giovanni Paolo Panini, Sebastiano Ricci, Antoine Watteau and Willem van de Velde the Younger.[27] Sculptures owned by Gibbs included a bust of Flora by François Girardon, a bust of Matthew Prior by Antoine Coysevox and busts of Alexander Pope and Gibbs by Rysbrack.[27]

Death and will

By 1743 Gibbs, who was fond of wine and food, was described as "corpulent".[28] In June 1749 Gibbs set out for the spa town of Aix-la-Chapelle for treatment: he long suffered from kidney stones and had lost weight and was in pain. He remained until September when he returned to London.[29] Gibbs never married.[30] He died in his London house on the corner of Wimpole Street and Henrietta Street on 5 August 1754 and was buried in St Marylebone Parish Church, and a modest wall tablet was erected with this inscription:[31][lower-alpha 1]

Underneath lye the Remains of JAMES

GIBBS Esqr. whose Skill in Architecture

appears by his Printed Works as well

as the Buildings directed by him,

Among other Legacys & Charitys

He left One Hundred Pounds towards

Enlarging this Church

He died Augt. 5th. 1754.

Aged 71.

In his will made on 9 May 1754, Gibbs left £1000, his Plate, and three houses in Marylebone to Lord Erskine in gratitude for favours from his father the late Earl of Mar. Further bequests included £1,400 and two houses in Marylebone and Argyll Ground Westminster to John Sherwine of Soho plus £100 to be given to a charity of Sherwine's daughters choice, to Robert Pringle of Clifton a Cavendish Square house and £400 and to Cosmo Alexander (1724–1772) a Scottish painter "my house I live in withall [sic] its furniture as it stands with pictures bustoes [sic] etc". Further bequests of £100 each went to William Thomas, Dr. William King, St Bartholomew's Hospital and the Foundling Hospital. The Trustees of Radcliffe Camera were given "all my printed books, Books of Architecture books of prints and drawings books of maps and a pair of globes with leather covers to be placed ... in the library... of which I was architect ... next to my Bustoe".[33]

Architecture

Early works

Mar attached Gibbs' name among the list of architects to be responsible for the new churches to be built under the Act for Fifty New Churches, and in 1713 he was appointed one of the Commission's two surveyors, the contemporary term for an architect, alongside Nicholas Hawksmoor. He held this post for two years, until he was forced out by the Whigs, because of his Tory sympathies, and replaced by John James.[34] During his tenure he completed his first important commission, the church of St Mary-le-Strand (1714–17), in the City of Westminster. A previous design had been prepared by the English Baroque architect Thomas Archer, which Gibbs developed in an Italian Mannerist style, influenced by the Palazzo Branconio dall'Aquila in Rome, attributed to Raphael, as well as incorporating elements from Wren.[35] Such strong Italian influence was not popular with the Whigs, who were now taking political control following the accession of King George I in 1714, leading to Gibbs' dismissal, and causing him to modify the foreign influences in his work.[36] Colen Campbell's Vitruvius Britannicus (1715), which promoted the Palladian style, also contains unfavourable comments regarding Carlo Fontana and St Mary-le-Strand.[36] Campbell went on to replace Gibbs as the architect of Burlington House around 1717, where the latter had designed the offices and colonnades for the young Lord Burlington.

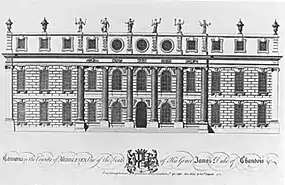

Other early designs include the house of Cannons, Middlesex (1716–20), for James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, and the tower of Wren's St Clement Danes (1719).[37] At Twickenham he designed the pavilion at Orleans House, called the Octagon Room, for a Scottish patron, James Johnston (1655–1737) former Secretary of State for Scotland, about 1720.[38] It is the only part of the house and grounds that has survived.

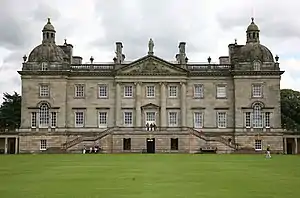

Country houses

Gibbs' mature style emerges in the early 1720s, with the house of Ditchley, Oxfordshire (1720–22), for George Lee, 2nd Earl of Lichfield. It typifies his conservative domestic manner, which changed little throughout the rest of his career.[39] His other houses include Sudbrooke Lodge, Petersham (1728), for the Duke of Argyll, works at Wimpole Hall, Cambridgeshire, for the 2nd Earl of Oxford, Patshull Hall, Staffordshire (1730) for Sir John Astley, and modifications to Colen Campbell's designs at Houghton Hall in Norfolk. Gibbs also completed the Gothic Temple (1741–48), a triangular folly at Stowe, Buckinghamshire, and now one of the properties leased and maintained by The Landmark Trust. Other garden buildings at Stowe include the pair of "Boycott Pavilions", which were altered by Giovanni Battista Borra in 1754 to replace the pyramidal stone roofs with more conventional domes.[40]

Churches

Gibbs designed one church for the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches, St Mary le Strand. Construction began in 1714 and it was complete by 1717. Between 1721 and 1726 Gibbs designed his most important and influential work, the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, located in Trafalgar Square, London. Gibbs' initial radical design for the commission was for a circular church, derived from a design by Andrea Pozzo; its illustration in Gibbs' book was to influence several adaptations by Neoclassical architects.[41] This was rejected by the commission, and Gibbs developed the present rectangular design. The layout and detailing of the building owes much to Wren, in particular the church of St James', Piccadilly.[42] However, Gibbs' innovation at St Martin's was to place the steeple centrally, behind the pediment.[43] By contrast, Wren's steeples were usually adjacent to the church, rather than within the walls. This apparent incongruity was criticised at the time,[43] but St Martin-in-the-Fields nevertheless became a model for church buildings, particularly for Anglican worship, across Britain and around the world.[41]

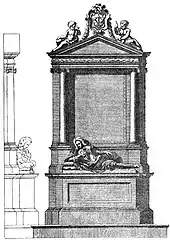

At the same time, Gibbs designed a chapel of ease for the 1st Earl of Oxford, now known as St Peter, Vere Street (1721–24).[39] In 1725 he designed All Saints', Derby, now Derby Cathedral, on similar lines to St Martin's, although at Derby the original gothic steeple was retained.[43] Gibbs, the first British architect to do so,[44] created numerous designs for funeral monuments, often collaborating with the sculptor Michael Rysbrack. In 1733 Gibbs was commissioned by Lord Foley to adapt the chapel from Cannons House (Gibbs was one of the architects involved in designing Cannons), as the parish church at Great Witley.[45]

St Bartholomew's Hospital

In 1723 Gibbs was appointed a governor of St Bartholomew's Hospital,[46] which led to him being commissioned to redesign the hospital. In 1728 he produced a design with four near identical blocks around a square 200 by 160 feet (61 by 49 m); he gave his services for free.[47] The first block to be built, the north, administration block was constructed from 9 June 1730, using Bath Stone (this would be used for all the blocks). It was finished in 1732 and contains the Great Hall and the main staircase, the walls of which are covered by murals painted by William Hogarth, depicting Christ healing the sick at the Pool of Bethesda and the parable of the good Samaritan. The other blocks contained wards. The south block was built from 1735 to 1740 (demolished 1937). the west block was built from 1743 to 1753; it was delayed due to the War of the Austrian Succession. The east block was built 1758–68 to Gibbs' design.

Universities

Gibbs worked at both Oxford and Cambridge Universities. He shares the credit, with James Burrough, for designing the Senate House at Cambridge.[48] The Fellows' Building at King's College (1724–30) is his work entirely. A simple composition, similar in style to his houses, the building is enlivened by a central feature incorporating an arch, within a doric portal, and a Diocletian window, all under a pediment. This mannerist composition of features from Wren and Palladio is an example of Gibbs' more adventurous Italian style.[43]

More adventurous still was Gibbs' last major work, the Radcliffe Camera, Oxford (1739–49). A circular library building was first planned by Hawksmoor around 1715, but nothing was done at the time. Sometime before 1736, new designs were submitted by Hawksmoor and Gibbs, with the latter's rectangular design being preferred. However, this plan was abandoned in favour of a circular plan by Gibbs, which drew on Hawksmoor's 1715 scheme, although it was very different in detail.[49] Gibbs' design saw him returning to his Italian mannerist sources, and in particular shows the influence of Santa Maria della Salute, Venice (1681), by Baldassarre Longhena. The building incorporates unexpected vertical alignments: for instance, the ribs of the dome do not line up with the columns of the drum, but lie in between, creating a rhythmically complex composition.[49]

Published works

Gibbs published the first edition of A Book of Architecture, containing designs of buildings and ornaments in 1728, dedicated to one of his patrons John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll. It was a folio of his building designs both executed and not, as well as numerous designs for ornaments and including 150 engraved plates covering 380 different designs. He was the first British architect to publish a book devoted to his own designs.[50] The major works illustrated include St Martin-in-the-Fields (including the unexecuted version with a circular nave), St Mary le Strand, the complete schemes for King's College Cambridge and the Public Building (including the Senate House) at Cambridge University, numerous designs for medium-sized country houses, garden building and follies, obelisks and memorial columns, church memorials and monuments, as well as wrought-iron work, fireplaces, window and door surrounds, Cartouche (design) and urns. The first page of the introduction included: '...such a Work as this would be of use to such Gentleman as might be concerned in Building, especially in the remote parts of the Country, where little or no assistance for designs can be procured'. It was intended to be a pattern book for both architects and clients, and became, according to John Summerson, "probably the most widely-used architecture book of the century, not only throughout Britain, but in the American colonies and the West Indies".[49] For example, Plate 58 was an inspiration for the river façade of Mount Airy, Richmond County, Virginia, and perhaps also for the floorplan of Drayton Hall in Charleston County, South Carolina.[51]

Other published works by Gibbs include The Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture (1732), which explained how to draw the Classical orders and related details and was used well into the 19th century,[49] and Bibliotheca Radcliviana subtitled A Short Description of the Radcliffe Library Oxford (1747) to celebrate the Radcliffe Camera, including a list of all the craftsmen employed in the building's construction as well as twenty-one plates.[52] In 1752 he published a two-volume translation of the Latin book De Rebus Emanuelis by a 16th-century Portuguese Bishop Jerome Osorio da Fonseca; his English title was The History of the Portuguese during the Reign of Emanuel. It is a history book with accounts of warfare, voyages of discovery from Africa to China (including descriptions of the religious beliefs of these countries) and also the initial colonisation of Brazil.[53]

List of architectural works

The following list includes Gibbs' most significant works.[54]

Secular works

- Senate House, Cambridge University 1721–30

- King's College, Cambridge, Fellows Building 1724–42, sole completed part of Gibbs' proposed rebuilding of the college

- Oxford Market House, Marylebone, London, 1726–37, demolished 1880–81

- St Bartholomew's Hospital, Smithfield, London 1728–68, rebuilding of medieval and later hospital,Gibbs south block demolished 1937

- Marylebone Court House, Marylebone, London, 1729–33, demolished 1803–04

- Radcliffe Camera, Oxford University 1736–49

- Hertford Town Hall, 1737 (unexecuted)

- Codrington Library, All Souls College, Oxford, completion of interior following the death of architect Nicholas Hawksmoor, 1740–50

- St John's College, Oxford, new screen in the Hall, 1743

Radcliffe Camera, Oxford University

Radcliffe Camera, Oxford University Interior, Radcliffe Camera, Oxford University

Interior, Radcliffe Camera, Oxford University

Detail of pediment, Senate House, Cambridge

Detail of pediment, Senate House, Cambridge East front, Fellows' Building, King's College Cambridge

East front, Fellows' Building, King's College Cambridge Great Hall, St Bartholomew's Hospital

Great Hall, St Bartholomew's Hospital Staircase with Hogarth mural paintings, St Bartholomew's Hospital

Staircase with Hogarth mural paintings, St Bartholomew's Hospital Centre of east block, St Bartholomew's Hospital

Centre of east block, St Bartholomew's Hospital

Ecclesiastical works

- St Mary le Strand, London, 1713–24

- Steeple, added to Christopher Wren's church of St Clement Danes, London, 1719–21

- St Martin-in-the-Fields, London, 1720–27

- Marybone Chapel (now St Peter's Vere Street, used as offices), London, 1721–24

- St Giles Church, Shipbourne, Kent, 1722–23, rebuilt 1880–81

- St Mary's Church, Mapleton, Derbyshire, c.1723

- Derby Cathedral, formerly All Saints, Derby, rebuilding of existing church except for the tower, 1723–26

- Lincoln Cathedral, strengthening of western towers, 1725–26

- St Michael and All Saints, Great Witley, Worcestershire, using decoration and fittings from the chapel at Cannons, 1733–47

- Chandos Mausoleum, St Lawrence, Whitchurch, Middlesex, for James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos, 1735–36

- Kirk of St Nicholas, Aberdeen, new nave 1741–55

- Turner Mausoleum, Kirkleatham Church, North Yorkshire, 1740

- Sir William Turner's Hospital Chapel, Kirkleatham 1741

- St Mary's Church, Patshull Hall, Staffordshire, 1742

West front, St Mary le Strand

West front, St Mary le Strand East front, St Mary le Strand

East front, St Mary le Strand Interior looking east, St Mary le Strand

Interior looking east, St Mary le Strand Steeple, St Clement Danes

Steeple, St Clement Danes West front, St Martin-in-the-Fields

West front, St Martin-in-the-Fields Interior looking west, St Martin-in-the-Fields

Interior looking west, St Martin-in-the-Fields The font, St Martin-in-the-Fields

The font, St Martin-in-the-Fields St Peter Vere Street

St Peter Vere Street The nave, Derby Cathedral

The nave, Derby Cathedral St Michael and All Saints, Great Witley

St Michael and All Saints, Great Witley Looking east, St Michael and All Saints, Great Witley

Looking east, St Michael and All Saints, Great Witley Chapel, Sir William Turner's Almshouses, Kirkleatham

Chapel, Sir William Turner's Almshouses, Kirkleatham Mausoleum on right, St Cuthberts Kirkleatham

Mausoleum on right, St Cuthberts Kirkleatham Mausoleum, St Cuthberts Kirkleatham

Mausoleum, St Cuthberts Kirkleatham South front, St Mary, Patshull

South front, St Mary, Patshull.jpg.webp) Chandos mausoleum, St Lawrence, Little Stanmore

Chandos mausoleum, St Lawrence, Little Stanmore

Church memorials

- Westminster Abbey, to John Dryden, poet, 1720–21

- Westminster Abbey, to John Sheffield, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Normanby, 1721–22

- Westminster Abbey, to John Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, 1721–23, sculpted by Francis Bird.

- Westminster Abbey, to Matthew Prior, 1721–23

- Westminster Abbey, to Ben Jonson, playwright, c.1723

- Westminster Abbey, to John Smith, 1723

- St Giles Church, Shipbourne, to Christopher Vane, 1st Baron Barnard, 1723, re-erected when the church was rebuilt

- Westminster Abbey, to William Johnstone, 1st Marquess of Annandale, James Johnstone, 2nd Marquess of Annandale and his wife Sophia Fairholm, 1723

- Westminster Abbey, to James Craggs the Younger, 1724–27

- St Mary's Amersham, to Montague & Jane Drake, 1725

- SS. Peter & Paul, Aston, to Sir John & Lady Bridgeman, 1726

- SS. Peter & Paul, Mitcham, to Sir Ambrose & Lady Crowley, c.1727

- St Mary's Bolsover, to Henry Cavendish, 2nd Duke of Newcastle, 1727–28, sculpted by Francis Bird.

- Westminster Abbey, Catherina Boevey, 1727–28, sculpted by John Michael Rysbrack.

- St Margaret's, Westminster, to Robert Stuart, 1728

- All Saints' Church, Bristol, to Edward Colston, slave-trader and philanthropist, 1728–29, sculpted by John Michael Rysbrack.

- All Saints, Maiden Bradley, to Sir Edward Seymour, 4th Baronet, 1728–30, sculpted by John Michael Rysbrack.

- Westminster Abbey, to Dr John Friend, 1730–31

- Turner Mausoleum, Kirkleatham Church, Monument to Marwood William Turner, 1739–41

- All Saints Soulbury, to Robert Lovett, c.1740

- St Marylebone Parish Church, own memorial (Gibbs was buried in the previous church, 1754), transferred to the present church

Edward Colston's Monument, All Saints' Church, Bristol

Edward Colston's Monument, All Saints' Church, Bristol

London houses

- Houses in the Privy Gardens, Whitehall, London, 1710–11, demolished 1807

- Burlington House, Piccadilly, wings and twin colonnades in forecourt, 1715–16, demolished

- Thanet House, Great Russell Street, Covent Garden 1719, demolished

- 9–11 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden 1723–27, demolished 1956; drawing room from No.11 preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum

- 52 Grosvenor Street, Mayfair alterations 1727

- Savile House, 6 Leicester Square, 1733, demolished

- 25 Leicester Square, 1733–34 demolished

- 49 Great Ormond Street, new library, 1734, demolished

- 16 Arlington Street, Mayfair 1734–40

- House in Mortimer Street, Marylebone, London 1735–40, demolished

- Houses in Argyll Street, Westminster 1736–1761

- House in Hanover Square, 1740, demolished

Burlington House forecourt, showing Gibbs' wings and a colonnade

Burlington House forecourt, showing Gibbs' wings and a colonnade Burlington House, one of the colonnades

Burlington House, one of the colonnades Drawing room from 11 Henrietta Street, now in V&A Museum

Drawing room from 11 Henrietta Street, now in V&A Museum

New country houses

- Sudbrook Park, Petersham, 1715–19 (now Richmond Golf Club)

- Cannons, one of several architects involved, 1716–19, demolished 1747

- Shrewsbury House, Isleworth, 1718–22, demolished c.1810

- Ditchley House, 1720-7

- Antony House, Cornwall, 1720-4

- Balveny House, Banffshire, 1724, demolished 1929

- House for Bartholomew Clarke and Hitch Young, Roehampton, c. 1724–29, demolished c. 1788

- Acton Place, Acton, Suffolk, c. 1725–26, demolished 1825

- Whitton Place, Whitton, London, 1725–31, demolished 1935

- Stowe House, various garden temples from 1726 to 1749

- Houghton Hall, one of several architects that worked on the building, c. 1727–35

- Kelmarsh Hall, 1728–32

- Kirkleatham Hall, designs 1728, probably not executed

- Gumley House, Isleworth, 1729

- Hamstead Marshall, work was started on a new house, 1739, but abandoned after the client died the year work started

- Catton Hall, 1741

- Patshull Hall, Staffordshire. 1742–54. The house was completed by William Baker of Audlem[55]

- Bank Hall, Warrington, 1749–50 (now Town Hall)

Sudbrook House

Sudbrook House Ditchley House

Ditchley House Cannons House

Cannons House Antony House, Cornwall

Antony House, Cornwall Eastern Boycott Pavilion, 1728, Stowe House, dome altered; it used to have a spire like the Turner Mausoleum

Eastern Boycott Pavilion, 1728, Stowe House, dome altered; it used to have a spire like the Turner Mausoleum The Fane of Pastoral Poetry, 1729, Stowe House

The Fane of Pastoral Poetry, 1729, Stowe House Palladian bridge, 1738, Stowe House, based on the bridge at Wilton House

Palladian bridge, 1738, Stowe House, based on the bridge at Wilton House Ruined Temple of Friendship, 1739, Stowe House

Ruined Temple of Friendship, 1739, Stowe House Gothic Temple, 1748, Stowe House

Gothic Temple, 1748, Stowe House Houghton Hall, showing two of Gibbs' domes

Houghton Hall, showing two of Gibbs' domes.jpg.webp) Kelmarsh Hall

Kelmarsh Hall Catton Hall

Catton Hall Patshull Hall

Patshull Hall Bank Hall, Warrington

Bank Hall, Warrington

Alterations to existing country houses

- Orleans House, Twickenham, the Octagon room, c.1716–21

- Alexander Pope's Villa, Twickenham, additions, 1719–20, demolished 1807–08

- Wimpole Hall, remodelling, including the Chapel 1722–27, new library and main staircase 1732

- Fairlawne, Shipbourne, extension, c.1723

- Hartwell House, Buckinghamshire, remodelling of interiors 1723–25

- Wentworth Castle, designed the wainscoting in the gallery 1724–25

- Compton Verney House, stables, 1740

- Hackwood Park, Hampshire, new portico, 1740

- Badminton House, further remodelling of north front already remodelled by William Kent, 1745

- Ragley Hall, interiors of the house, original architect Robert Hooke had left unfinished, 1751–c.1760

Orleans House, Gibbs' Octagon on the left

Orleans House, Gibbs' Octagon on the left.jpg.webp) Octagon, Orleans House

Octagon, Orleans House.jpg.webp) Interior of the Octagon, Orleans House

Interior of the Octagon, Orleans House Wimpole Hall, Gibbs' Library on the right

Wimpole Hall, Gibbs' Library on the right The Chapel, Wimpole Hall

The Chapel, Wimpole Hall Badminton House, north front as remodelled by Gibbs

Badminton House, north front as remodelled by Gibbs

,

See also

- Category:James Gibbs buildings

Notes

- ↑ His home on Henrietta Street became the site of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1910.[32]

References

- ↑ Howard Colvin, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600–1840, 3rd ed. 1995, s.v. "Gibbs, James".

- ↑ Summerson, pp.330, 333

- ↑ Friedman, p.3

- 1 2 Friedman, p.2

- 1 2 Friedman, p.4

- 1 2 Friedman, p.5

- ↑ Friedman, p.6

- 1 2 3 4 Friedman, p.7

- ↑ Little, p.25

- ↑ Friedman, p.13

- ↑ Friedman, p.20

- 1 2 3 Friedman, p.10

- ↑ Friedman, p.21

- ↑ Friedman, p.23

- ↑ page 21 St Martin-in-the-fields, Malcolm Johnson, 2005, Phillimore, ISBN 1-86077-323-0

- ↑ Page 45, 'Anecdotes of Painting in England' 1771

- ↑ pages 27 to 29, the Architectural Drawings Collection of King's College, Cambridge, Allan Doig, 1979, Avebury Publishing

- 1 2 Friedman, p.225

- ↑ Friedman, p.15

- 1 2 Friedman, p.214

- 1 2 3 Friedman, p.16

- ↑ Friedman, p.222

- ↑ Friedman, p.22

- ↑ page xii, The Building Accounts of the Radcliffe Camera, S.G. Gillam, 1958, Oxford University Press

- ↑ page xviii, The Building Accounts of the Radcliffe Camera, S.G. Gillam, 1958, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Little, p.164

- 1 2 Little, p.23

- ↑ Little, p.168

- ↑ Friedman, p.18

- ↑ Little, p.163

- ↑ "Marylebone Pages 242-279 The Environs of London: Volume 3, County of Middlesex. Originally published by T Cadell and W Davies, London, 1795". British History Online. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ↑ Hunting, P (1 January 2005). "The Royal Society of Medicine". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 81 (951): 45–48. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2003.018424. ISSN 0032-5473. PMC 1743179. PMID 15640428.

- ↑ Friedman, pp.17–20

- ↑ Summerson, p.280

- ↑ Summerson, p.286

- 1 2 Summerson, p.324

- ↑ Summerson, p.325

- ↑ Illustrated in Gibbs, A Book of Architecture plate 71: Colvin 1995.

- 1 2 Summerson, p.326

- ↑ Colvin 1995.

- 1 2 Summerson, p.327

- ↑ Summerson, p.328

- 1 2 3 4 Summerson, p.330

- ↑ Colvin 1995

- ↑ Page 325-6, Terry Friedman, James Gibbs, 1984, Yale University Press

- ↑ Friedman, p.213

- ↑ "Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer. 25 June 1726 "William Gibbs, King's Surveyor" has provided a scheme for rebuilding St Bartholomew's Hospital".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ T. P. Hudson, "James Gibbs's Design for University Buildings at Cambridge", The Burlington Magazine 114 (1972): 844.

- 1 2 3 4 Summerson, p.333

- ↑ page 210, British Architectural Books and Writers 1556–1785, Eileen Harris, 1990, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-38551-2

- ↑ The Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc., "Palladio and Patternbooks in Colonial America."

- ↑ Little, p.36

- ↑ Little, p.155

- ↑ Based on Friedman, pp.290–326

- ↑ Victoria County History of Staffordshire, Vol 20, 165–7

Bibliography

- Terry Friedman and Peter Burman, James Gibbs as a Church Designer: An Exhibition Celebrating the Restoration of the Cathedral Church of All Saints at Derby, 1972, Chapterhouse Press, 1972.

- Friedman, Terry (1984) James Gibbs. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03172-6

- Little, Bryan (1955) The Life and Work of James Gibbs 1682–1754. Batsford Books.

- Summerson, John (1993) Architecture in the United Kingdom, 1530–1830 9th edition. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05886-4

External links

- James Gibbs, Twickenham Museum