Jan Kochanowski | |

|---|---|

Jan Kochanowski | |

| Born | 1530 |

| Died | August 22, 1584 (aged 53–54) |

| Resting place | Zwoleń |

| Other names | Jan z Czarnolasu |

| Alma mater | University of Padua |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1550–1584 |

| Known for | Major influence on Polish poetry; first major Polish poet |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouse |

Dorota Podlodowska

(m. 1575) |

| Children | 7 |

| Signature | |

| |

Jan Kochanowski (Polish: [ˈjan kɔxaˈnɔfskʲi]; 1530 – 22 August 1584) was a Polish Renaissance poet who wrote in Latin and Polish and established poetic patterns that would become integral to Polish literary language. He has been called the greatest Polish poet before Adam Mickiewicz (the latter, a leading Romantic writer)[1][2] and one of the most influential Slavic poets prior to the 19th century.[3]: 188 [4]: 60

In his youth Kochanowski traveled to Italy, where he studied at the University of Padua, and to France. In 1559 he returned to Poland, where he made the acquaintance of political and religious notables including Jan Tarnowski, Piotr Myszkowski (whom he briefly served as courtier), and members of the influential Radziwiłł family.

From about 1563, Kochanowski served as secretary to King Sigismund II Augustus. He accompanied the King to several noteworthy events, including the Sejm of 1569 (held in Lublin), which enacted the Union of Lublin, formally establishing the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In 1564 he was made provost of Poznań Cathedral. By the mid-1570s he had largely retired to his estate at Czarnolas, where in 1584 he died, most likely of a heart attack.

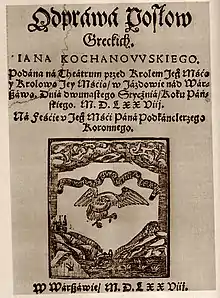

All his life, Kochanowski was a prolific writer. Works of his that are pillars of the Polish literary canon include the 1580 Treny (Laments), a series of nineteen threnodies (elegies) on the death of his daughter Urszula; the 1578 tragedy Odprawa posłów greckich (The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys), inspired by Homer; and Kochanowski's Fraszki (Epigrams), a collection of 294 short poems written during the 1560s and 1570s, published in three volumes in 1584.[1][5][6] One of his major stylistic contributions was the adaptation and popularization of Polish-language verse forms.[7]: 32

Life

Early life (1530–1550s)

Details of Jan Kochanowski's life are sparse and come primarily from his own writings.[8]: 61 He was born in 1530 at Sycyna, near Radom, Kingdom of Poland, to a Polish szlachta (noble) family of the Korwin coat of arms.[3]: 185 His father, Piotr Kochanowski, was a judge in the Sandomierz area; his mother, Anna Białaczowska, was of the Odrowąż family.[3]: 185 Jan had eleven siblings and was the second son; he was an older brother of Andrzej Kochanowski and Mikołaj Kochanowski, both of whom also became poets and translators.[3]: 185 [4]: 61 [9]

Little is known of Jan Kochanowski's early education. At fourteen, in 1544, he was sent to the Kraków Academy.[3]: 185 Later, around 1551-52, he attended the University of Königsberg, in Ducal Prussia (a fiefdom of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland); then, from 1552 to the late 1550s, Padua University in Italy.[3]: 185-186 At Padua, Kochanowski studied classical philology[4]: 61 and came in contact with the humanist scholar Francesco Robortello.[3]: 185 During his "Padua period", he traveled back and forth between Italy and Poland at least twice, returning to Poland to secure funding and attend his mother's funeral.[3]: 185-186 [4]: 61 Kochanowski concluded his fifteen-year period of studies and travels with a visit to France, where he visited Marseilles and Paris and met the poet Pierre de Ronsard.[3]: 186 [4]: 61 It has been suggested that one of his travel companions in that period was Karl von Utenhove, a future Flemish scholar and poet.[3]: 186

Career and royal court (1559–1570s)

In 1559 Kochanowski permanently returned to Poland, where he was active as a humanist and a Renaissance poet. He spent the next fifteen years as a courtier, though little is known about his first few years on return to Poland. The period covering the years 1559-1562 is poorly documented. It can be assumed that the poet established closer contacts with the court of Jan Tarnowski, the voivode of Kraków, and the Radziwiłłs.[10] In mid-1563, Jan entered the service of the Vice Chancellor of the Crown and bishop Piotr Myszkowski, thanks to whom he received the title of royal secretary. There are no details concerning the duties performed by Jan at the royal court. On 7 February 1564 Kochanowski was admitted to the provostship in the Poznań cathedral, which Myszkowski had renounced.[11]: 114–121

Around 1562–63 he was a courtier to Bishop Filip Padniewski and Voivode Jan Firlej. From late 1563 or early 1564, he was affiliated with the royal court of King Sigismund II Augustus, serving as a royal secretary. During that time he received two benefices (incomes from parishes). In 1567 he accompanied the King during an episode of the Lithuanian-Muscovite War, itself a part of the Livonian War: a show of force near Radashkovichy. In 1569 he was present at the sejm of 1569 in Lublin which enacted the Union of Lublin establishing the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[3]: 186 [4]: 61

Late life and Czarnolas (1571–1584)

From 1571 onward, Kochanowski began to spend more time at a family estate in the village of Czarnolas located near Lublin.[3]: 186 In 1574, following the decampment of Poland's recently elected King Henry of Valois (whose candidacy to the Polish throne Kochanowski had supported), Kochanowski settled permanently in Czarnolas to lead the life of a country squire. In 1575 he married Dorota Podlodowska (daughter of Sejm deputy Stanisław Lupa Podlodowski),[3]: 186 with whom he had seven children. At Czarnolas, following the death of his daughter Ursula, which affected him greatly, he wrote one of his most memorable works, Treny (the Laments).[3]: 187

In 1576 Kochanowski was a royal envoy to the sejmik (local assembly) in Opatów.[12] Despite the urging of people close to him, including the Polish nobleman and statesman Jan Zamoyski, he decided not to take an active part in the political life of the court. Nonetheless, Kochanowski remained socially active on a local level and was a frequent visitor to Sandomierz, the capital of his voivodeship.[13] On October 9, 1579, the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Stefan Batory signed in Vilnius the nomination of Kochanowski as the standard-bearer of Sandomierz.[11]: 291–292 [14]

Kochanowski died, probably of a heart attack, in Lublin on 22 August 1584, aged 54. He was buried in the crypt of a parish church in Zwoleń.[3]: 187 [4]: 61 [15][16] According to historical records, at least two tombstones were erected for Kochanowski, one in Zwoleń and another in Policzno, neither of which survives. In 1830 Kochanowski's remains were moved to his family crypt by the Zwoleń church authorities. In 1983 they were returned to the church, and in 1984 another funeral was held for the poet.[17]

In 1791 Kochanowski's reputed skull had been removed from his tomb by Tadeusz Czacki, who kept it in his estate at Porycko.[18] He later gave it to Izabela Czartoryska; by 1874, it had been transported to the Czartoryski Museum, where it currently resides. However, anthropological studies in 2010 showed it to be the skull of a woman, possibly Kochanowski's wife.[19]

Works

Kochanowski's earliest known work may be the Polish-language Pieśń o potopie (Song of the Deluge), possibly composed as early as 1550. His first publication was the 1558 Latin-language Epitaphium Cretcovii, an epitaph dedicated to his recently deceased colleague Erazm Kretkowski. Kochanowski's works from his youthful Padua period comprise mostly elegies, epigrams, and odes.[3]: 187

Upon his return to Poland in 1559, his works generally took the form of epic poetry and included the commemoratives O śmierci Jana Tarnowskiego (On the Death of Jan Tarnowski, 1561) and Pamiątka wszytkimi cnotami hojnie obdarzonemu Janowi Baptiście hrabi na Tęczynie (Remeberance for the All-Blessed Jan Baptist, Count at Tęczyna, 1562-64); the more serious Zuzanna (1562) and Proporzec albo hołd pruski (The Banner, or the Prussian Homage, 1564); the satirical[1][5] social- and political-commentary poems Zgoda (Accord, or Harmony, ca. 1562) and Satyr albo Dziki Mąż (The Satyr, or the Wild Man, 1564); and the light-hearted Szachy (Chess, ca. 1562-66).[3]: 187 The last, about a game of chess, has been described as the first Polish-language "humorous epic or heroicomic poem".[20]: 62

Some of his works can be seen as journalistic commentaries, before the advent of journalism per see, expressing views of the royal court in the 1560s and 1570s, and aimed at members of parliament (the Sejm) and voters.[20]: 62–63 This period also saw most of his Fraszki (Epigrams), published in 1584 as a three-volume collection of 294 short poems reminiscent of Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron. They became Kochanowski's most popular writings, spawning many imitators in Poland.[3]: 187 Czesław Miłosz, 1980 Nobel lureate Polish poet, calls them a sort of "very personal diary, but one where the personality of the author never appears in the foreground".[20]: 64 Another of Kochanowski's works from the time is the non-poetic political-commentary dialogue, Wróżki (Portents)..[3]: 188

A major work from that period was Odprawa posłów greckich (The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys, written ca. 1565-66 and first published and performed in 1578; translated into English in 2007 by Bill Johnston as The Envoys[21]). This was a blank-verse tragedy that recounted an incident, modeled after Homer, leading to the Trojan War.[9][22] It was the first tragedy written in Polish, and its theme of the responsibilities of statesmanship resonates to this day. The play was performed on 12 January 1578 in Warsaw's Ujazdów Castle at the wedding of Jan Zamoyski and Krystyna Radziwiłł (Zamoyski and the Radziwiłł family were among Kochanowski's important patrons).[3]: 188 [23][24] Miłosz calls The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys "the finest specimen of Polish humanist drama".[20]: 68

During the 1560s and 1570s, Kochanowski completed a series of elegies titled Treny, which were later published in three volumes in 1584 (in English generally titled Laments rather than Threnodies). The poignant nineteen elegies mourn the loss of his cherished two-and-a-half-year-old daughter Urszula. In 1920, the Laments were translated into English by Dorothea Prall, and in 1995 by the duo, Stanisław Barańczak and Seamus Heaney.[6] As with Kochanowski's Fraszki, it became a perennially popular wellspring of a new genre in Polish literature.[3]: 188 [4]: 64 Milosz writes that "Kochanowski's poetic art reached its highest achievements in the Laments": Kochanowski's innovation, "something unique in... world literature... a whole cycle... centered around the main theme", scandalized some contemporaries, as the cycle applied a classic form to a personal sorrow – and that, to an "insignificant" subject, a young child.[20]: 75–76

In 1579 Kochanowski translated into Polish one of the Psalms, Psalterz Dawidów (David's Psalter). By the mid-18th century, at least 25 editions had been published. Set to music, it became an enduring element of Polish church masses and popular culture. It also became one of the poet's more influential works internationally, translated into Russian by Symeon of Polotsk and into Romanian, German, Lithuanian, Czech, and Slovak.[3]: 188 [25] His Pieśni (Songs), written over his lifetime and published posthumously in 1586, reflect Italian lyricism and "his attachment to antiquity", in particular to Horace,[4]: 65–66 and have been highly influential for Polish poetry.[3]: 187

Kochanowski also translated into Polish several ancient classical Greek and Roman works, such as the Phenomena of Aratus and fragments of Homer's Illiad.[3]: 188 Kochanowski's notable Latin works include Lyricorum libellus (Little Book of Lyrics, 1580), Elegiarum libri quatuor (Four Books of Elegies, 1584), and numerous occasional poems. His Latin poems were translated into Polish in 1829 by Kazimierz Brodziński, and in 1851 by Władysław Syrokomla.[1][5]

In some of his works, Kochanowski used Polish alexandrines, wherein each line comprises thirteen syllables, with a caesura following the seventh syllable.[20]: 63 Among works published posthumously, the historical treatise O Czechu i Lechu historyja naganiona (Woven Story of Czech and Lech) offered the first critical literary analysis of Slavic myths, focusing on the titular origin myth about Lech, Czech, and Rus'.[3]: 188

Views

Like many persons of his time he was deeply religious, and a number of his works are inspired by religion. However, he avoided taking sides in the strife between the Catholic Church and the Protestant denominations; he stayed on friendly terms with figures of both Christian currents, and his poetry was viewed as acceptable by both.[20]: 62

Influence

Kochanowski has been described as the greatest Polish poet prior to Adam Mickiewicz.[1][2] The Polish literary historian Tadeusz Ulewicz writes that Kochanowski is generally regarded as the foremost Renaissance poet not only in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth but across all Slavic nations. His primacy remained unchallenged until the advent of the 19th-century Polish Romantics (aka Polish Messianists), especially Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki, and Alexander Pushkin in Russia.[3]: 188

According to Ulewicz, Kochanowski both created modern Polish poetry and introduced it to Europe.[3]: 189 An American Slavicist, Oscar E. Swan, holds that Kochanowski was "the first Slavic author to attain excellence on a European scale".[26] Similarly Miłosz writes that "until the beginning of the nineteenth century, the most eminent Slavic poet was undoubtedly Jan Kochanowski" and that he "set the pace for the whole subsequent development of Polish poetry".[4]: 60 The British historian Norman Davies names Kochanowski the second most important figure of the Polish Renaissance, after Copernicus.[27]: 119 Polish poet and literary critic Jerzy Jarniewicz called Kochanowski "the founding father of Polish literature".[28]

Kochanowski never ceased writing in Latin. One of his major achievements was the creation of Polish-language verse forms that made him a classic for his contemporaries and posterity.[7]: 32 He greatly enriched Polish poetry by naturalizing foreign poetic forms, which he knew how to imbue with a national spirit.[1][5] Kochanowski, writes Davies, can be seen as "the founder of Polish vernacular poetry [who] showed the Poles the beauty of their language".[27]: 119

American historian Larry Wolf argues that Kochanowski "contributed to the creation of a vernacular culture in the Polish language";[29] Polish literary historian Elwira Buszewicz describes him as "the 'founding father' of elegant humanist Polish-language poetry";[25] and American Slavicist and translator David Welsh writes that Kochanowski's greatest achievement was his "transformation of the Polish language as a medium for poetry".[26]: 136 [30][3]: 187 Ulewicz credits Kochanowski's Songs as most influential in this regard, while Davies writes that "Kochanowski's Psalter did for Polish what Luther's Bible did for German".[31]: 259 Kochanowski's works also influenced the development of Lithuanian literature.[24]

Legacy

Kochanowski's first published collection of poems was his David's Psalter (printed 1579).[20]: 63 A number of his works were published posthumously, first in a series of volumes in Kraków in 1584–90, ending with Fragmenta albo pozostałe pisma (Fragments, or Remaining Writings).[3]: 189 [5] That series included works from his Padua period and his Fraszki (Epigrams).[3]: 187 1884 saw a jubilee volume published in Warsaw.[3]: 189 [5]

In 1875 many of Kochanowski's poems were translated into German by H. Nitschmann.[5] In 1894 Encyclopedia Britannica called Kochanowski "the prince of Polish poets".[32] He was, however, long little known outside Slavic-language countries. The first English-language collection of Kochanowski's poems was released in 1928 (translations by George R. Noyes et al.), and the first English-language monograph devoted to him, by David Welsh, appeared in 1974.[33] As late as the early 1980s, Kochanowki's writings were generally passed over or given short shrift in English-language reference works.[34] However, more recently further English translations have appeared, including The Laments, translated by Stanisław Barańczak and Seamus Heaney (1995), and The Envoys, translated by Bill Johnston (2007).[33][21][35]

Kochanowski's oeuvre has inspired modern Polish literary, musical, and visual art. Fragments of Jan Kochanowski's poetry were also used by Jan Ursyn Niemcewicz in the libretto for the opera Jan Kochanowski, staged in Warsaw in 1817.[36] In the 19th century, musical arrangements of Lamentations and the Psalter gained popularity. Stanisław Moniuszko wrote songs for bass with piano accompaniment to the texts of Lamentations III, V, VI and X.[37] In 1862, the Polish history painter Jan Matejko depicted him in the painting Jan Kochanowski nad zwłokami Urszulki (Jan Kochanowski and his Deceased Daughter Ursula). In 1961 a museum (the Jan Kochanowski Museum in Czarnolas) opened on Kochanowski's estate at Czarnolas.[3]: 189

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- 1 2 Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Ulewicz, Tadeusz (1968). "Jan Kochanowski". Polski słownik biograficzny (in Polish). Vol. 13. Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich - Wydawawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Milosz, Czeslaw (24 October 1983). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- 1 2 Smusz, Aleksandra (11 September 2021). "Jan Kochanowski - informacje o autorze, biografia". lekcjapolskiego.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 17 October 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- 1 2 Zaremba, Charles (30 September 2021). "A child's death, the poet's immortality. Jan Kochanowski's Laments". In Bilczewski; Stanley, Bill; Popiel, Magdalena (eds.). The Routledge World Companion to Polish Literature. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-45359-1.

- ↑ Milosz, Czeslaw (24 October 1983). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- 1 2 Kotarski, Edmund. "Jan Kochanowski". Virtual Library of Polish Literature. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ↑ Korolko, Mirosław (1985). Jana Kochanowskiego żywot i sprawy: materiały, komentarze, przypuszczenia (in Polish). Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna. pp. 86–90. ISBN 978-83-214-0379-3.

- 1 2 Garbaczowa, Maria; Urban, Wacław, eds. (1985). Źródła urzędowe do biografii Jana Kochanowskiego [Official sources for the biography of Jan Kochanowski] (in Polish). Warszawa: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

- ↑ Kriegseisen, Wojciech (1991). Sejmiki Rzeczypospolitej szlacheckiej w XVII i XVIII wieku (in Polish). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Sejmowe. p. 57. ISBN 83-7059-009-8.

- ↑ Urban, Wacław (1981). "Poznań skarbnicą materiałów do Kochanowskiego". Pamiętnik Biblioteki Kórnickiej. 17: 290. ISSN 0551-3790.

- ↑ Józef, Gacki (1869). O rodzinie Jana Kochanowskiego, o jej majętnościach i fundacyach: Kilkanaście pism urzędowych (in Polish). Warszawa: Gebethner i Wolff. pp. 75–76.

- ↑ "Krypta ze szczątkami Jana Kochanowskiego dostępna dla turystów". Dzieje.pl (in Polish). Warsaw: Polish Press Agency and Polish History Museum. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ↑ Pisze, Jakub (3 September 2012). "W poszukiwaniu wiecznego spoczynku – tułaczka szczątków Jana z Czarnolasu". HISTORIA.org.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ↑ Pelc, Janusz (2001). Kochanowski. Szczyt renesansu w literaturze polskiej (in Polish). Warszawa: Polskie Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 143. ISBN 83-01-01196-3.

- ↑ Zgorzelski, Czesław (1930). "Czesław Zgorzelski, Sycyna, Czarnolas i Zwoleń w opisach wędrówek po kraju". Alma Mater Vilnensis (in Polish). Wilno. 9: 37.

- ↑ Mrowiec, Małgorzata (15 November 2010). "Głosy sceptyków nad żeńską czaszką Jana Kochanowskiego". Dziennik Polski (in Polish). Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Milosz, Czeslaw (24 October 1983). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- 1 2 Kochanowski, Jan (2007). The envoys. Bill Johnston, Krzysztof Koehler. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka. ISBN 978-83-7188-870-0. OCLC 226295845.

- ↑ Paczkowski, Grzegorz (31 July 2021). "Odprawa posłów greckich - streszczenie – Jan Kochanowski, Odprawa posłów greckich - opracowanie – Zinterpretuj.pl" (in Polish). Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ↑ Bogucka, Maria; Kieniewicz, Stefan, eds. (1984). Warszawa w latach 1526-1795 (in Polish) (Wyd. 1 ed.). Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawn. Nauk. pp. 157–58. ISBN 83-01-03323-1. OCLC 11843473.

- 1 2 Niedźwiedź, Jakub (2008). "Jan Kochanowski, poeta Litewski". Acta historica universitatis Klaipedensis. 16: 179–187. ISSN 1392-4095.

- 1 2 Buszewicz, Elwira (2023). "Jan Kochanowski's Psalter – a Source of Polish Poetry and Mirror of the Human Mind". The Biblical Annals. 13 (70/3): 419–437. doi:10.31743/biban.14572. ISSN 2083-2222. S2CID 260784636.

- 1 2 Swan, Oscar (1975). "Review of Jan Kochanowski". The Slavic and East European Journal. 19 (3): 344–346. doi:10.2307/306298. ISSN 0037-6752. JSTOR 306298.

- 1 2 Davies, Norman (24 February 2005). God's Playground A History of Poland: Volume 1: The Origins to 1795. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-925339-5.

- ↑ Jarniewicz, Jerzy (March 2016). "From Miłosz to Kochanowski: The uses of Polish poetry in Seamus Heaney's work". Journal of European Studies. 46 (1): 24–36. doi:10.1177/0047244115617714. ISSN 0047-2441. S2CID 164055835.

- ↑ Wolff, Larry (17 June 2014). "Cultural Precedence and Reciprocity between Eastern Europe and Western Europe: Some American Reflections on Jerzy Jedlicki's "Europe's Eastern Borderland"". East Central Europe. 41 (1): 105–111. doi:10.1163/18763308-04102006. ISSN 1876-3308.

- ↑ Welsh, David J. (1974). Jan Kochanowski. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-2490-5.

- ↑ Davies, Norman (31 May 2001). Heart of Europe: The Past in Poland's Present. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-164713-0.

- ↑ The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature. Maxwell Sommerville. 1894.

- 1 2 Segel, Harold B. (1976). "Review of Jan Kochanowski". Slavic Review. 35 (3): 583–584. doi:10.2307/2495176. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2495176. S2CID 164224517.

- ↑ ULEWICZ, TADEUSZ (1982). "The Portrait of Jan Kochanowski in the Encyclopaedias of Non-Slavic Countries: A Critical Survey". The Polish Review. 27 (3/4): 3–16. ISSN 0032-2970. JSTOR 25777888.

- ↑ Kochanowski, Jan (1995). Laments. Stanisław Barańczak, Seamus Heaney (1st ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-18290-6. OCLC 32237008.

- ↑ Niziurski, Mirosław (1981). "Muzyczne opracowania tekstów Jana Kochanowskiego". Rocznik Świętokrzyski. IX: 199–210.

- ↑ Opieński, Henryk (7 June 1930). "Kurier Poznański". Vol. 261. p. 25.

Further reading

- Welsh, David J. (1974). Jan Kochanowski. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-2490-5.

External links

- Digitized works by Jan Kochanowski in Polish Digital National Library

- Works by Jan Kochanowski at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Jan Kochanowski at Internet Archive

- Works by Jan Kochanowski at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Kochanowski with commentary at WolneLektury.pl

- Selection of translated poems

- Translations of Jan Kochanowski Archived 3 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa

- Translations of Jan Kochanowski by Michał J. Mikoś

- Jan Kochanowski at culture.pl

- Jan Kochanowski collected works (Polish)