| ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

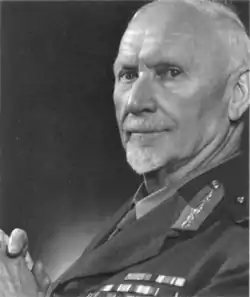

Jan Christiaan Smuts, OM (24 May 1870 – 11 September 1950) was a prominent South African and Commonwealth statesman and military leader. He served as a Boer General duning the Boer War, a British General during the First World War and was appointed Field Marshal during the Second World War. In addition to various Cabinet appointments, he served as Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa from 1919 to 1924 and from 1939 to 1948. He played a leading part in the post war settlements at the end of both world wars, making significant contributions towards the creation of both the League of Nations and the United Nations.

This article is about Jan Smuts in the government of South Africa when part of the British Empire, from the Transvaal's defeat at the end of the Second Boer War in 1902 until the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910. Smuts emerged from the Boer War as one of the foremost Afrikaner leaders. Working closely with Louis Botha, Smuts engineered the restoration of autonomy. Having won the elections to the restored Transvaal Parliament, Smuts and Botha proceeded to negotiate beneficial terms of unification.

Out of Their Hands

Back to the Day Job

The Second Boer War had irrevocably changed the face of South Africa, but, for Smuts, it was back to work as usual. Whilst Christiaan De Wet, Koos de la Rey, and Louis Botha toured Europe, hailed as conquering heroes, Smuts returned to his former day job, as a mediocre lawyer. Smuts was as restless in this capacity as ever, and yearned to take part in politics again. Alas for Smuts, the British dominance of South Africa since Vereeniging made it almost impossible for an Afrikaner, no matter how well versed in the English language or British thinking, to break through. More worrying for Smuts, many Boers disapproved of his, and others', leadership during the war: some wished for a fight to the death, whilst some wished that the war had ended after the fall of Pretoria.

Having seen the generosity of the British treasury in London, Botha came to the conclusion a unified South Africa, within the British Empire, would serve both Briton and Afrikaner well. However, Baron Milner was the enemy of the Afrikaner, being chiefly responsible for creating a British monopoly on government posts (called Milner's Kindergarten). He saw no place for Dutch-speakers in the government of South Africa. To counter Milner, and to unite the Afrikaners, the former generals of the Transvaal army, including Smuts, formed the Het Volk party in January 1905. The objective of the party was straightforward enough: self-government, and, ultimately, the creation of a unified South African state.

Changing of the Guard

In 1905, Milner's term as High Commissioner came to an end, and, for Smuts, it could not come a minute too soon. Milner was replaced by a more conciliatory man, Lord Selborne, who was in deep admiration of Smuts. Selborne was keen to discuss any manner of constitutional arrangement, but, without the backing of the Conservative government in London, Selborne could advance the process no further than Smuts could. Of course, the Conservative government was dependent upon the support of the British people, and that soon dried up.

Later that year, the Conservative government resigned, and was replaced by a Liberal one under Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, which was later confirmed at a general election in February 1906. The new government was led by some of the more active anti-Imperialists in Parliament, including a few that had sympathised with the Boer republics in the South African War. Smuts recognised this opportunity, and set off for London as soon as he heard the news. When he arrived, he was astonished to find so much opposition to the Conservatives' policy in South Africa.

Smuts negotiated from a starting position of full self-government for the Transvaal within British South Africa. Whilst this was dismissed by the Conservatives as unrealistic and counter-productive, most Liberal politicians saw things Smuts' way. Campbell-Bannerman failed to understand the Afrikaners' refusal to work with Milner. Regardless, he was compelled to agree. The Liberal government had been elected partly on the back of opposition to the Chinese indentured labour that had saved the gold mines. Campbell-Bannerman realised that the Chinese workers could not be removed, for that would cripple the economy, and knew that the Afrikaners could never be outnumbered by the British in South Africa. Thus, he decided to pass the buck to the Afrikaners, under whose remit of self-government the miners would fall. He persuaded the cabinet to accept Smuts' demands.

Back in Charge

Election

In December 1906, a new constitution for the Transvaal was drawn up, under which an immediate election would find a government. This gave Het Volk two advantages. First, it was fighting an election according to a constitution that it had written. Second, it was fighting an election at a time at which it was the predominant force in Transvaal politics. Nonetheless, neither Botha nor Smuts, the two leaders took the task of election too lightly.

Across the Transvaal they toured, whipping up public support for their cause and their candidates. Botha was a natural-born politician, and the crowds loved him. Less popular was the shy and distant Smuts. Despite his quiet nature, and the controversies of the Boer War, Smuts was comfortably elected in the Wonderboom constituency, near Pretoria. Across the board, Het Volk had scored a massive victory. Botha became the prime minister, forming his government solely from Het Volk. Chief amongst his ministers was Smuts, who became both the Colonial Secretary and the Education Secretary: two of the top positions.

Ruling the Transvaal

Immediately, Botha set off on a diplomatic tour of Europe, taking advantage of his celebrity, and left Smuts in charge of the Transvaal. Smuts took a disliking to the bureaucracy, the discussion and the compromise of government. He saw action as the best response to crisis. Crisis came soon, in the form of the Dutch Reformed Church. The Calvinist movement pressed Smuts to take advantage of self-government, by making Afrikaans and Calvinism compulsory for schoolchildren. Although a Calvinist himself, Smuts had grown out of his former zealotry, and found that he could not agree with their aims. He wanted a secular state, and he wanted the next generation to be well versed in the English language, not Afrikaans.

Smuts was attacked for being irreligious, or even blasphemous, and the pastors of the Dutch Reformed Church campaigned heavily against Smuts. In the end, though, there was little that the church could do in the face of the government, backed by the Selborne administration in Cape Town. Smuts knew that, if there was one thing Afrikaners could do, it was to bear a grudge. The Reformed Church, counting three-quarters of Afrikaners amongst its members, could certainly wield great political power.

Gandhi

A great number of immigrants from other parts of the Empire flooded to South Africa. The two largest groups were Malays and South Asians. For the Afrikaners, this was a problem. They threatened to undercut European wages, and to take a slice of the wealth created by the mines. Smuts sought to clamp down on the stream of immigrants by any method necessary. He tore into the gangs that smuggled them into the country, limited Indian employment rights, and had each foreign worker register with the government. Opposing Smuts was an Indian lawyer by the name of Mohandas Gandhi.

Gandhi responded to the Transvaal's heavy-handedness with non-violent resistance, as he would in India years later. Smuts imprisoned the most vocal opponents in the Asian population, including Gandhi. The press was outraged, and caricatured Smuts as though he were another Paul Kruger: Crude, fierce, and unyielding. Smuts caved in to Gandhi's passive resistance, letting the Indians go but offering Gandhi no definite promise of concessions.

Incidents such as these were few and far between. Smuts' battle with the Dutch Reformed Church was more representative of his tenure in power. He knew how to fight fire with fire, but Gandhi got under Smuts' skin without so much as raising his fists. The Indian affairs aside, by 1909, Smuts had created a very strong government, backed by a booming economy. Nonetheless, the issue of Union was still as pressing as ever.

Creating a Country

Smuts' Vision

As it always had, friction developed and increased between the component parts of South Africa. After Vereeniging, a compromise had been reached on railway harmonisation and customs union, but, with its architect, Lord Milner, out of the picture, a new agreement had to be reached. Although treated, politically, as parts of one whole, the Transvaal and the three colonies could not be more dissimilar. All of South Africa's wealth came from the Transvaal, whilst the three colonies would have been destitute without the Transvaal's need for support services. Botha and Smuts held all the cards.

Smuts argued that there could be no South Africa without complete political union. During the war, Smuts had grown to despise the enmity of the British and the Boers, and to realise the futility of South African fratricide. Smuts made impassioned pleas to the Transvaal Parliament: "There is only one road to salvation, the road to Union and to a South African Nation".

For Smuts, union meant unitary. He had examined the failures of the American federal system, and was disappointed at its inertia and its great disparities. Not all parties were agreed. Smuts, having faith in his intellect and rhetoric, called for a convention to be held in Durban, where Briton and Afrikaner alike could be persuaded of his ambition.

Convention and Union

The summer of 1908-9 was stiflingly hot in Durban. Nonetheless, in October 1908, delegates from across South Africa braved the heat and humidity to attend Smuts' convention. Smuts had planned carefully his line of attack, tailored to the needs and demands of each delegate, and he was sure that he would succeed. He knew that compromise on all issues would be impossible, so he focused on the general principles, intending to leave more technical and less significant matters to the future South African Parliament.

The delegates, though, jealously guarded their own interests, and there were numerous disputes: On the powers of the provincial councils, the extension of the franchise, the location of the capital, the official language of the Union, and even the size of the standard track gauge. Smuts resolved these issues with careful wording, vague promises, and compromise.

The most hard-fought battles were between Smuts and the Orange delegates. Steyn and Hertzog were indomitable, and keen not to allow the Transvaal to dictate the general message of the Afrikaner people. Smuts was willing to compromise to achieve consensus. He agreed to create three separate capitals, at Cape Town, Pretoria, and Bloemfontein. He agreed to give Dutch equal status to English in the constitution. Nevertheless, Smuts could not concede on any of his broader point of Union. Steyn and Hertzog were opposed to any Union that would reduce the powers of the provincial parliaments.

Whilst Steyn and Hertzog could never accept such a conclusion, the other delegates already had. Gradually, over time, the resolve of the Orange delegates was worn down. The summer was drawing to a close, and the environment better set for conciliation. Smuts lay out his proposals in one final speech, drawing on the constitutions of a dozen nations, and argued passionately in favour of his ideal. In the end, the Orange delegates were forced to agree. They could not afford the Orange colony to become a footnote in South Africa, isolated from Smuts' grand ambitions. Besides, Steyn and Hertzog had secured many concessions that would compensate for the loss of sovereignty.

Smuts drew up a final draft, to which all the delegates agreed. The constitution was ratified by the Parliaments of the Cape Colony, Orange River Colony, and the Transvaal. Natal even held a referendum, which was passed by a massive majority of the white electorate. Smuts and Botha took the constitution to London to be passed by the British Parliament. With the aid of more impassioned Smuts speeches, The Act of Union was passed. It was given Royal Assent by King Edward VII in December 1909. The Union of South Africa was born.