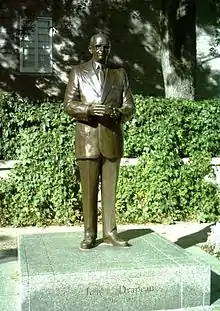

Mayor Jean Drapeau | |

|---|---|

Jean Drapeau in 1954 | |

| 37th Mayor of Montreal | |

| In office 1954–1957 | |

| Preceded by | Camillien Houde |

| Succeeded by | Sarto Fournier |

| In office 1960–1986 | |

| Preceded by | Sarto Fournier |

| Succeeded by | Jean Doré |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 February 1916 Montreal, Quebec, Canada |

| Died | 12 August 1999 (aged 83) Montreal, Quebec, Canada |

| Political party | Civic Party of Montreal |

| Spouse | Marie-Claire Boucher |

| Alma mater | Université de Montréal |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

Jean Drapeau CC GOQ (18 February 1916 – 12 August 1999) was a Canadian politician who served as mayor of Montreal, Canada for 2 non-consecutive terms from 1954 to 1957 and from 1960 to 1986. Major accomplishments of the Drapeau Administration include the development of the Montreal Metro entirely underground mass transit subway system running on 'whisper quiet' rubber wheels, a successful international exposition Expo 67 as well as the construction of a major performing arts centre, the Place des Arts. Drapeau also secured the hosting of the 1976 Summer Olympics and was instrumental in building the Olympic Stadium and then world's tallest inclined tower. Drapeau was responsible for securing a Major League Baseball franchise, with the creation of the Montreal Expos in 1969. Drapeau's main legacy is Montreal's attainment of global status under his administration.

Early life and career

The son of Joseph-Napoléon Drapeau and Alberta (Berthe) Martineau, Jean Drapeau was born in Montreal in 1916. His father, an insurance broker, city councillor and election worker for the Union nationale, introduced him to politics. Jean Drapeau studied law at the Université de Montréal.

Drapeau was a protégé of nationalist priest Lionel Groulx in the 1930s and 1940s,[1] and was a member of André Laurendeau's anti-conscription Ligue pour la défense du Canada. In 1942, he ran as a candidate of the nationalist Bloc populaire, which opposed Canadian conscription during World War II, in a federal by-election. Drapeau lost the election. He was also a Bloc populaire candidate in the 1944 provincial election but was badly defeated in his Montreal constituency.[1]

He began his practice as a criminal lawyer in Montreal in 1944. During the Asbestos strike of 1949, he took on the legal defence of some of the strikers.[1]

In 1945, he married Marie-Claire Boucher. They had three sons.

Mayor of Montreal

Drapeau's profile grew as the result of his role in a public inquiry led by Pacifique Plante into police corruption in the early 1950s. When Camillien Houde retired as mayor of Montreal, Drapeau was well poised to succeed him.[1]

Drapeau was elected mayor of Montreal in 1954 at the age of 37, as the candidate of the Civic Action League, on a platform of cleaning up the administration. He ran an exceptionally wide-flung campaign, uniting a large coalition of voters from English-speaking and French-speaking parts of Montreal. Drapeau's charismatic demeanor, accessible style, and his fluency in both English and French (unprecedented for a mayoral candidate) propelled him to such popularity. In 1957, he lost to Sarto Fournier who was backed by the Premier of Quebec Maurice Duplessis,[1] but Drapeau was elected again in the election of 1960 at the helm of his newly formed Civic Party. He was re-elected without interruption until he retired from political life in 1986. By the end of the decade, Montreal was a virtual one-party state, with Drapeau and his party only facing nominal opposition in City Hall.

During Drapeau's tenure as mayor, he initiated the construction of the Montreal Metro mass transit subway system with trains running on whisper quiet rubber wheels, Place des Arts, and Expo 67, the universal exposition of 1967.[1] To support the expenditures, Drapeau created the first public lottery in Canada in 1968, which he called simply a "voluntary tax", an idea that would later gain favour and become enlarged by the provincial government by creating Loto-Québec corporation in 1970. The 1970s were busy times for the preparation of the 1976 Summer Olympics. Cost overruns and scandals forced the Quebec government to take over the project eight months before the Games opened.[2] Almost a year after the Games had ended, Quebec Premier René Lévesque appointed a commission to investigate the high cost overruns of the games, led by Quebec supreme court judge Albert Malouf. The inquiry found that Drapeau had made some serious and costly mistakes. The debt taken on by the city under Drapeau, coupled with a crime wave as young upstarts challenged the mafia that controlled the city's underworld, helped lead to the Murray-Hill riot, unrest caused by a wildcat strike by the Montreal police over pay on 7 October 1969. Drapeau retired ahead of the 1986 elections. Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney appointed Drapeau to the position of Canadian ambassador to UNESCO in Paris.[1]

Despite the nationalism of his youth, Drapeau remained neutral during the 1980 Quebec referendum.[1]

In 1967, Drapeau was made a Companion of the Order of Canada and received the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada's gold medal.[3] He was named a Grand Officer of the National Order of Quebec in 1987.

After his death in 1999 (at age 83), Drapeau was interred in the Notre Dame des Neiges Cemetery in Montreal.

One of the biggest parks in Montreal, Parc Jean-Drapeau, composed of Notre Dame Island and Saint Helen's Island in the middle of the Saint Lawrence River, site of the universal exposition of 1967, was renamed in his honour, as was the Metro station serving the park.

Drapeau was also instrumental in the demolition of the historic Van Horne Mansion on Sherbrooke street; a classic greystone house built in 1869 for John Hamilton, president of the Merchant's Bank of Montreal. The building was controversially bulldozed in the middle of the night by developer David Azrieli in 1973 under the mayoralty of Drapeau, who declared that it was impossible to preserve it for cultural reasons because it was not part of Quebec's culture - Hamilton and Van Horne being Anglophone Quebecers (Hamilton was from Ontario and Van Horne was American). It was replaced by a sixteen-storey concrete tower. The mansion's destruction sparked the creation of the heritage preservation group Save Montreal. Journalist William Weintraub includes the house and its demolition in his 1993 documentary, The Rise and Fall of English Montreal, identifying the significance of the building to the local Anglo community's heritage.

Quotations

During a public transport strike, Drapeau said: "If bus and metro subway train drivers are not at work tomorrow morning, I will personally drive a metro train. If you want to ensure something gets done, the best way is to do it yourself."

Drapeau said "The Olympics can no more lose money than a man can have a baby,"[4] after announcing the budget for the Montreal Olympic games. Following the Olympics, the city was left with a debt of $1 billion, leading to the Aislin editorial cartoon of a pregnant Drapeau calling Canadian physician and abortion rights advocate Henry Morgentaler.[5]

Drapeau was on a TV show every week where Montrealers could phone and discuss live with Drapeau specific problems a particular citizen were having. Drapeau knew every lane and every street in the city by heart. One caller mentioned a street light not working. Drapeau, on live TV, and without any prior knowledge of the issue raised answered: "Are you talking about the street light on the west side of rue Fabre, precisely the one facing 4429 Fabre near Mont-Royal street?"

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 McKenna, Brian (12 June 2011). "Jean Drapeau". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022.

- ↑ "Jean Drapeau: Hardly your average mayor". Google News Archive. The Montreal Gazette. 3 June 1980. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023.

- ↑ "RAIC Gold Medal". Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. Archived from the original on 16 June 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ↑ "1976: Queen opens Montreal Olympics". CBC Digital Archives. Canadian Broadcasting Company. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ↑ "Aislin looks back at the 1976 Summer Olympics", Montreal Gazette, 27 July, 2016.

External links

- Canadian Encyclopedia entry on Jean Drapeau

- CBC Archives Drapeau's vision of bringing the Eiffel Tower to Montreal for Expo 67.

- Jean Drapeau Collection McGill University Library & Archives.