Jessie Catherine Kinsley | |

|---|---|

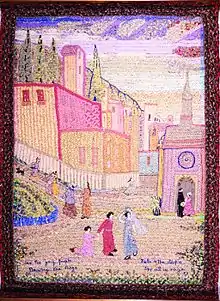

Kinsley alongside one of her braidings | |

| Born | March 26, 1858 Oneida, New York |

| Died | February 10, 1938 Oneida, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Braided Tapestries |

| Notable work | Things Not of Man's Devising, Bewitched, Tree of Life, The Picnic |

| Movement | Arts and Crafts |

Jessie Catherine Kinsley (March 26, 1858 – February 10, 1938) was an American folk artist known for braidings — an artistic medium of her own devising which grew out of her interest in colonial-style braided rugs.

Kinsley began making braidings at the age of 50, and created many pieces for friends and family. One author described her as having "typified the domestic artist”.[1] Kinsley’s works attracted attention, particularly in the Arts and Crafts world. In 1917-18 alone, her creations were displayed prominently in the annual exhibit of the National Society of Craftsmen (New York), the Craftsmen’s Exhibition of the Carnegie Institute (Pittsburgh), and the Applied Arts Exhibition of the Art Institute of Chicago.[2]

Kinsley was also a prolific diarist and correspondent. A selection of those writings and a memoir were collected into a book titled A Lasting Spring: Jessie Catherine Kinsley, Daughter of the Oneida Community, which was edited by her granddaughter Jane Kinsley Rich and historian Nelson Blake. A Lasting Spring details Kinsley's experiences growing up in a utopian community and her subsequent life.[3]

Biography

Jessie Catherine Baker was born in the Oneida Community (1848-1880), a utopian community of religious perfectionists led by John Humphrey Noyes. In keeping with the practices of the Community, she was raised in communal style.[4] Women in the Community held a wide variety of jobs, but they were typically responsible for the mending and sewing, which would have helped Jessie develop her skills from an early age.[5] The utopian community voted to disband in 1880 when Jessie was 22.[6] The Community then became a joint-stock corporation, eventually evolving into Oneida Limited.[7]

Jessie married former Community member Myron Kinsley (1836-1907) in February 1880.[8] Myron was assigned by the newly formed company to supervise the construction and operation of the Oneida Silverplate and Canning factories in Niagara Falls, N.Y. Together the couple had three children, and Jessie also helped raise Myron’s daughter from a Community relationship. After living in Niagara Falls and Chicago, the Kinsleys returned to Oneida, New York.[9]

At age 50, Jessie Catherine Kinsley began studying painting with Kenneth Hayes Miller, a leading proponent of urban genre painting. Kinsley was dissatisfied with her painting, but was inspired to create braidings. She wrote:

"So gradually, I found the fascination of this medium to my mind and fingers, and began making pictures in a wholly original way from my own designs...and unlike my painted pictures, braided pictures grew into satisfactory proportions and some large tapestries came with the years."[10]

Her work quickly grew in complexity. As Beverley Sanders noted in an article about Kinsley, she went from "chair mats to large wall hangings that resemble traditional tapestries in their subtlety of color, complexity of design and sensuous texture."[11] Kinsley created braidings until just before her death in 1938.

Style

Kinsley's braidings are "elaborate, exquisitely colored tapestries...that evoke a fairy-tale world" in the words of one craft historian.[12] Kinsley found inspiration for her braidings in poetry, and many of her pieces have quotations from poems.[13] A series of landscapes, Woodlands and To a Green Thought include verses from The Garden by Andrew Marvell, while her piece Shepherd Boy was inspired by William Blake's poem The Lamb.[14]

Kinsley once stated that she approached her designs as a painter would, by first sketching out the design and then "using the braids just as a painter uses his brush--making braids take on movement-direction-perspective." She stripped cloth into bands and made her braids by attaching three bands to the back of a chair and braiding them together. Instead of using wool or cotton scraps, Kinsley generally used silks for their more vibrant colors.[15] She assembled the braids and basted them onto the pattern she had created, bending them to cover every part of the pattern before sewing them together.[16] By the 1920s, Kinsley was creating large pieces. Her first large-scale piece, titled Things Not of Man's Devising, measured 7 feet by 7 feet. The large pieces were often divided into sections, like a triptych, to make the work possible.

Exhibitions and collections

Much of Kinsley’s work is housed at the Oneida Community Mansion House, a museum that was once home to the Oneida Community. The museum has a permanent display of her work in an exhibit titled “The Braidings of Jessie Catherine Kinsley.”[17]

Kinsley’s braidings have also been featured in a 2004 exhibit “Braidings and Benches: The Oneida Community and the Arts and Crafts Movement” at Colgate University and at an exhibit titled “The Braided Wall Hangings of the Oneida Community” at Fountain Elms, Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in 1978.[18] Kinsley's braiding The Picnic is in the collection at The Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College.[19]

Kinsley’s papers, including letters, sketches, and journals, are archived at the Oneida Community Mansion House. Other Kinsley papers are located in Syracuse University’s Oneida Community Collection in the Special Collections at Bird Library.[20]

References

- ↑ Schwartz, Helen (Winter 2000). "Jessie Kinsley and Her Braidings". Heritage. New York State Historical Association Magazine. 16.

- ↑ Wonderly, Anthony (2010). The Braidings of Jessie Catherine Kinsley. Oneida, New York: Oneida Community Mansion House.

- ↑ Kinsley, Jessie (1983). Rich, Jane Kinsley with the assistance of Nelson M. Blake (ed.). A Lasting Spring: Jessie Catherine Kinsley, Daughter of the Oneida Community. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. pp. 59.

- ↑ Jennings, Chris (2016). Paradise Now:The Story of American Utopianism. New York: Random House. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-8129-9370-7.

- ↑ Klee-Hartzell, Marlyn (Fall 1993). "'Mingling the Sexes':The Gendered Organization of Work in the Oneida Community". Syracuse University Library Associates Courier (2): 67.

- ↑ Klaw, Spencer (1993). Without Sin:The Life and Death of the Oneida Community. New York: Allen Lane, the Penguin Press. pp. 270. ISBN 0-7139-9091-0.

- ↑ Carden, Maren (1971). Oneida: Utopian Community to Modern Corporation. New York: Harper & Row.

- ↑ Kinsley, Jessie (1983). A Lasting Spring. Syracuse University Press. pp. 59.

- ↑ Linnabery, Ann Marie (February 13, 2016). "Niagara Discoveries: A visit to the home of Myron H. Kinsley".

- ↑ Kinsley, Jessie (1983). A Lasting Spring. Syracuse University Press. p. 104.

- ↑ Sanders, Beverly (May 1981). "A Scrap Bag Palette". American Craft.

- ↑ Sanders, Beverly (1981). "A Scrap Bag Palette". American Craft: 14.

- ↑ Schwartz, Helen (2000). "Jessie Kinsley and her Braidings". Heritage.

- ↑ Horton, Janice (2012). "Braids into Brushstrokes:An Artist Finds her Medium". Piecework: 44.

- ↑ Schwartz, Helen (Winter 2000). "Jessie Kinsley and her Braidings". Heritage.

- ↑ Sanders, Beverly (1981). "A Scrap Bag Palette". American Craft: 17.

- ↑ "Collections and Exhibitions". Oneida Community Mansion House.

- ↑ "Oneida Community descendants play role in Picker show". news.colgate.edu. Colgate University. March 29, 2004.

- ↑ "Wellin Collections". Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art, Hamilton College.

- ↑ "Special Collections: Religious and Utopian Communities". library.syr.edu. Syracuse University.