The Viscount of Inhaúma | |

|---|---|

The Viscount of Inhaúma around the age of 56, c. 1864 | |

| Born | 1 August 1808 Lisbon, Kingdom of Portugal |

| Died | 8 March 1869 (aged 60) Rio de Janeiro, Empire of Brazil |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Rank | Admiral |

| Battles/wars | |

| Children | Antônio Carlos de Mariz e Barros |

| Other work | Minister of Navy |

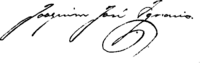

| Signature |  |

Joaquim José Inácio, Viscount of Inhaúma (Portuguese: [iɲaˈũmɐ]; 1 August 1808 – 8 March 1869), was a naval officer, politician and monarchist of the Empire of Brazil. He was born in the Kingdom of Portugal, and his family moved to Brazil two years later. After Brazilian independence in 1822, Inhaúma enlisted in the Brazilian navy. Early in his career during the latter half of the 1820s, he participated in the subduing of secessionist rebellions: first the Confederation of the Equator, and then the Cisplatine War, which precipitated a long international armed conflict with the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata.

Throughout the chaos that characterized the years when Emperor Dom Pedro II was a minor, Inhaúma remained loyal to the government. He helped quell a military mutiny in 1831 and was involved in suppressing some of the other rebellions that erupted during that troubled period. He saw action in the Sabinada between 1837 and 1838, followed by the Ragamuffin War from 1840 until 1844. In 1849, after spending two years in Great Britain, Inhaúma was given command of the fleet that was instrumental in subduing the Praieira revolt, the last rebellion in imperial Brazil.

During the 1850s, Inhaúma held a series of bureaucratic positions. He entered politics in 1861 as a member of the Conservative Party. He became a cabinet member and was given the position of navy minister. Inhaúma also became the first person to hold the Ministry of Agriculture portfolio, albeit briefly. The first professional firefighter corps in Brazil was formed during his tenure as agriculture minister. In late 1866, Inhaúma was appointed commander-in-chief of the fleet engaged in the Paraguayan War. During the fighting, he achieved the rank of admiral, the highest in the Brazilian armada. He was also awarded a noble title, eventually being raised from baron to viscount. In 1868, he was elected to the national legislature's lower house, but never assumed office.

Although he successfully prosecuted his operations in the war against Paraguay, Inhaúma's leadership was encumbered by his hesitating and procrastinating behavior. While in command in the war zone, he became mentally exhausted and contracted an unknown disease. Seriously ill, Inhaúma returned to the national capital in early 1869 and died shortly thereafter. Although historical works have not given much coverage to Inhaúma, some historians regard him among the greatest of the Brazilian navy officers.

Early life

Birth and education

Joaquim José Inácio[upper-alpha 1] was born in Lisbon, Kingdom of Portugal. Although the date on his birth certificate was 30 July 1808, his mother claimed that the correct birthdate was two days later, on 1 August.[1][2] He personally affirmed that the later date was accurate,[2] as did his younger brother, who was his biographer.[3] Regardless, some biographers, including Joaquim Manuel de Macedo[4] and Carlos Guilherme Haring,[5] have persisted in citing the date mistakenly entered on the birth certificate.

Joaquim Inácio's parents were José Vitorino de Barros and Maria Isabel de Barros. In 1808, the Portuguese Royal family moved to Brazil, then the largest and wealthiest colony of Portugal. Two years later, on 10 July 1810, José de Barros arrived in the Brazilian capital, Rio de Janeiro. As a crew member of the frigate D. Carlota, he was charged with transporting what remained of the personal property of Prince Regent Dom João, later King Dom João VI to Brazil.[6] José de Barros also brought his family on the voyage, including Joaquim Inácio, who was then one year and eight months old.[3][7] Joaquim Inácio had an older sister named Maria[3][7] and six younger siblings (who were born after the arrival in Brazil), among them Bento José de Carvalho and Antônio José Vitorino de Barros.[8]

As was common at the time, Joaquim Inácio began his education at home and was later enrolled in Seminário de São José (Saint Joseph School) and after that, in Seminário São Joaquim (Saint Joachim School), which became Pedro II School in 1837. His teachers included Januário da Cunha Barbosa, who later became one of the leading figures in the Brazilian independence movement.[9] Joaquim Inácio chose to follow his father, a naval officer who achieved the rank of second lieutenant, in his choice of a career.[10] On 20 November 1822 at the age of 14, Joaquim Inácio was admitted as aspirante a guarda-marinha (aspiring midshipman or naval cadet) at the Navy Academy. On 11 December 1823, he graduated from the academy, majoring in mathematics, with the rank of guarda-marinha (midshipman). As he had in previous studies at other schools, Joaquim Inácio proved to be a brilliant student.[9] Among his colleagues at the academy was Francisco Manuel Barroso da Silva (later Baron of Amazonas) whom he befriended.[11]

Rebellions in north and south

When Prince Dom Pedro (later Emperor Dom Pedro I), son and heir of King João VI, led the movement for the independence of Brazil, Joaquim Inácio was one of several Portuguese-born residents who sided with the Brazilian cause and joined the armada (as the Brazilian Navy was called in the imperial era). On 16 January 1824, he began his service aboard Pedro I, a ship of the line and flagship of First Admiral Thomas Cochrane, Marquis of Maranhão. Joaquim Inácio did not fight in any battles, as the Portuguese enemy forces had surrendered by that time. His baptism of fire came a few months later with the advent of the Confederation of the Equator, a secessionist rebellion in Brazil's northeastern provinces. He was given the command of the cutter Independente and aided in the suppression of rebels in Rosário do Itapecuru, a village in the province of Maranhão. The rebellion was over by early 1825,[12] and on 25 February Joaquim Inácio was promoted to second lieutenant.[9]

In June 1825, Joaquim Inácio traveled to Brazil's far south to quell a secessionist rebellion in the province of Cisplatina. The insurgents were aided by the United Provinces of the River Plate (later Argentina), which led to the Cisplatine War. Joaquim Inácio served as first officer aboard the patache Pará, which was stationed in Colônia de Sacramento (present-day Colonia del Sacramento), the second most important town in Cisplatina.[9] By late February 1826, Sacramento was besieged by enemy forces. Joaquim Inácio was sent ashore and placed in charge of the Santa Rita battery, composed of sailors and cannons from the Brazilian ships. He took an active part in successfully repelling enemy attacks upon Sacramento on 7 February, 26 February and 14 March.[13][14]

On the night of 10 March 1826 and in the midst of the siege of Sacramento, Joaquim Inácio boarded a small, unarmed boat accompanied by a single army officer and passed unnoticed through a line of nineteen enemy ships under cover of darkness. He reached the main Brazilian fleet on the morning of the next day and requested assistance from Vice-Admiral Rodrigo José Ferreira Lobo, the commander-in-chief of the naval forces operating in the war. Joaquim Inácio returned to Sacramento two days later under heavy enemy fire along with three boats carrying supplies and arms. Although welcomed as a hero in the besieged town, he was passed over for a promotion. Disregard for this achievement was due to his lack of wealth and family connections, a burden which continued to thwart his career for years to come.[15]

Loss of Cisplatina

In February 1827, Joaquim Inácio was transferred to the crew of the corvette Duquesa de Goiás, in which he was to take part in the invasion of Carmen de Patagones, a village in the northeast of the United Provinces that served as a port for corsairs. The Duquesa de Goiás sank during the expedition, killing several crew members. Joaquim Inácio insisted on being the last officer to leave the vessel.[16] He was next given the command of the schooner Constança. The invasion of Carmen was a complete failure, and the Brazilian land forces were defeated and taken prisoner. On 7 March, while Joaquim Inácio awaited news of the invasion, the Constança and another schooner were surrounded by enemy vessels. After a desperate battle, he was taken captive after refusing to surrender.[17]

The Brazilian prisoners were placed together aboard a brig bound for Buenos Aires, capital of the United Provinces. They suffered severe hardship, starving and almost naked. Under the leadership of Joaquim Inácio, the Brazilians staged an uprising, took control of the ship and made prisoners of their captors. The ship successfully eluded two corvettes and one schooner-brig that had pursued them, and sailed on to Montevideo, capital of Cisplatina, which they reached in safety on 29 August 1827.[18] Despite Joaquim Inácio's daring rescue of Brazilian prisoners of war from both the invasion's land-based forces and from the two schooners, he was reprimanded by the commander-in-chief Vice-Admiral Rodrigo Pinto Guedes, Baron of Rio da Prata (who had replaced Rodrigo Lobo) for the loss of the Constança.[19][20]

Joaquim Inácio returned to Rio de Janeiro in October, his tour of duty having lasted three years. He was then sent back to Cisplatina aboard the frigate Niterói and in December he became the first officer of the barque Grenfell.[20] On 17 February 1828, he fought in the Battle of Quilmes. During the engagement, the Brazilian barque-brig (three-masted barque) Vinte e nove de agosto ran aground and was about to be boarded. Seeing this, Joaquim Inácio positioned the Grenfell near the threatened vessel and protected her until she could be freed by the rising tide. Both ships returned to the battle, which resulted in a Brazilian victory.[21] Brazil's efforts in the war were ultimately in vain, as it eventually relinquished Cisplatina, which became the independent nation of Uruguay. In July 1829, Joaquim Inácio again returned to Rio de Janeiro,[22][23] and on 17 October he was promoted to first lieutenant.[24]

Rebellions

Further uprisings

On 17 March 1831, Joaquim Inácio married Maria José de Mariz Sarmento. Her father was an officer in the Portuguese navy whose own father and paternal grandfather had also been military officers.[25][26] Maria José de Mariz Sarmento belonged to the noble Portuguese family of Mariz and was a parent of Antônio de Mariz, one of the founders of Rio de Janeiro, as narrated in 1857 by José de Alencar in his novel The Guarani. Joaquim Inácio and Maria José had several children: Ana Elisa de Mariz e Barros, Joaquim José Inácio, Antônio Carlos de Mariz e Barros and Carlota Adelaide de Mariz e Barros. The couple also had a girl and a boy, named Constança and Manuel respectively, both of whom died in infancy.[27]

A month and a half after Joaquim Inácio's marriage, Emperor Pedro I abdicated and sailed to Europe. Since the former emperor's son and heir Dom Pedro II was a minor, a regency was formed, and more than a decade of instability and turmoil ensued. On 6 October 1831, navy artillerymen, held under suspicion of plotting a mutiny, escaped the presiganga (prison ship) in which they had been confined. Joaquim Inácio commanded the schooner Jaguaripe which, along with other vessels, had been guarding the prison ship. Seeing that the artillerymen had set sail for Rio de Janeiro, Joaquim Inácio and a few men took a boat to warn the city. They encountered musket fire from the artillerymen, who then changed course for the nearby Ilha das Cobras (Island of the Snakes) in the face of strong opposition from the mainland. They were defeated the next day when three columns of men from the Volunteer Soldier-Officers Battalion and Permanent Municipal Guard Corps invaded the island.[28]

In January 1833, strong winds forced the old and poorly built Jaguaripe aground off Santa Marta beach in the southern province of Santa Catarina, where it sank. Joaquim Inácio was again the last to abandon ship. The entire crew was rescued, though he himself barely survived. Joaquim Inácio and his younger brother Bento José (who was also a navy officer) stayed afloat by holding onto a leather basket until reaching the shore.[upper-alpha 2] Afterward, Joaquim Inácio was court martialed and absolved of any wrongdoing.[29][30] On 5 April 1833, he was given command of the barque-brig Vinte e nove de agosto (the same ship he had saved in 1828) and sailed to the province of Maranhão. The last time he had been in the province was in 1825. He remained stationed in the provincial capital (São Luís) as chief of the port until his return to Rio de Janeiro on 30 December 1836.[30][31] He was transferred to the steam barque Urânia in 1837 and later, on 19 July of the same year, to the brig Constança (a different vessel than the schooner he lost in 1827).[32]

Joaquim Inácio departed Rio de Janeiro on 11 August 1837 for Salvador, capital of the province of Bahia. He had been charged with delivering the prisoner Bento Gonçalves (leader of the rebellion known as the Ragamuffin War that had ravaged Rio Grande do Sul since 1835) to a military fortress.[33][34] On 7 September 1837, Joaquim Inácio was promoted to captain lieutenant.[35] A couple of months later, the Sabinada rebellion erupted in Salvador. The rebels freed Bento Gonçalves, who escaped back to Rio Grande do Sul. Joaquim Inácio took part in the blockade of that city until the end of the rebellion in March 1838.[36] His lack of family connections and political influence again stymied his career in 1839, when he was passed over for a well-deserved promotion.[37]

Restoration of order

On 23 July 1840, Pedro II was declared of age and Joaquim Inácio was among the naval officers representing the armada in the delegation that greeted the young emperor.[38][39] The rise of Pedro II to head the central government resulted in a slow, but steady, restoration of order in the country. On 17 December, Joaquim Inácio was named inspetor do arsenal de marinha (inspector of the navy shipyard) in Rio Grande, the second most important town in Rio Grande do Sul.[38][39] The province was still troubled by the Ragamuffin rebellion. He led the sailors manning the trenches surrounding Rio Grande and fought the Ragamuffins when they attacked the town in July 1841.[39][40]

The Ragamuffin menace was halted when the government dispatched field marshal (present-day divisional general) Luís Alves de Lima e Silva (then Baron, later Duke of Caxias) in 1842. The Baron of Caxias had been the second in command of the Volunteer Soldier-Officers Battalion when it put down the mutiny of navy artillerymen in 1831. He and Joaquim Inácio established a close, lifelong friendship.[41] Joaquim Inácio was promoted to frigate captain on 15 March 1844.[42] Soon afterward, Joaquim Inácio was relieved of command, at his own request, after becoming ever more at odds with his superior.[39][40] On 2 April 1845, he was assigned command of the frigate Constituição and in October returned to Rio Grande do Sul, which by that time had been pacified. He escorted the Emperor during his tour of the Brazilian southern provinces.[43] Pedro II was favorably impressed with the character of the ship's captain. Dark-haired and of average height, Joaquim Inácio was joyful and pleasant. He was also hard-working, intelligent and well-learned.[44][45] In addition to his native Portuguese, he could also speak and write in Latin, English and French.[46]

In August 1846, Joaquim Inácio sailed the Constituição to Devonport (then-known as Plymouth Dock) in the United Kingdom, where the ship was to undergo repairs. He paid a visit there to the elderly Thomas Cochrane, Marquis of Maranhão, who queried him regarding Brazil's state of affairs.[42][47] Joaquim Inácio returned to Brazil in May 1847 and was assigned to bureaucratic tasks.[42] In April 1848, he was stationed, again at the helm of the Constituição, in Bahia province. Later that year, the Praieira revolt erupted in the nearby province of Pernambuco. In early November, Joaquim Inácio assumed the command of the fleet protecting Recife, capital of Pernambuco. He sent many of his sailors ashore to aid in the town's defense. Recife was attacked by rebels on 2 February 1849. The insurgent attackers were defeated, and soon afterward the last rebellion of Brazil's imperial era came to an end.[48] Joaquim Inácio, who fought in the streets with his men, later remarked: "It was not a battle, but a diabolical hunt from which I have escaped by miracle."[42][49] He was awarded with a promotion to captain of sea and war on 14 March.[50]

Bureaucratic positions and politics

Navy commissions

On 26 May 1850, Joaquim Inácio was appointed inspector of the naval shipyard at Rio de Janeiro.[50] He played no role in the Platine War that pitted the Empire against the Argentine Confederation (the successor state of the United Provinces of the River Plate), which lasted from late 1851 until early 1852. He spent that period in the capital overseeing the construction and repair of several sailing vessels and steamships for the Brazilian armada.[51] He was promoted to chief of division (modern-day rear admiral) on 3 March 1852.[51]

Throughout the 1850s, Joaquim Inácio was assigned to a succession of mostly bureaucratic positions. After being removed from the office of inspector on 8 November 1854, eleven days later he was named captain of the port of Rio de Janeiro (for both the city and province).[51] From 1854 until 1860, he was appointed a member of various navy boards that dealt with matters ranging from promotions and equipment purchases to war spoils and standardization of naval uniforms.[52][53] On 2 November 1855, Joaquim Inácio was named adjutant (equivalent to adjutant general) to the navy minister.[53][54] On 2 December 1856, he was promoted to chief of fleet (modern vice admiral)[54][55] and made a Fidalgo Cavaleiro da Casa Imperial (Knight Nobleman of the Imperial Household), which raised him to a position ranking above the members of chivalry orders and below the titled nobles (barons, counts, etc.).[55][56] Joaquim Inácio also became a member and vice-president of the naval council (an advisory board) on 24 July 1858.[54][55]

As had also been the case with his predecessors, the rank of adjutant was seen by Joaquim Inácio as an embarrassment. Inside the armada administration, it denoted the most important office, as it was filled by an officer who acted as the navy minister's direct representative in the armada. Even so, the title of "adjutant" was itself perceived as demeaning. Joaquim Inácio later complained: "In what part of the world ... does the navy minister have a general officer as an adjutant? What is an adjutant, other than a young officer who transmits orders, and even messages, he receives from his chief?" He concluded: "Thus the title of adjutant cannot encumber an officer who supervises the armada's discipline and answers for it." His request to have the designation for the position changed to a more appropriate title was ignored. He also felt slighted that many of his proposals to the navy boards regarding improvements were not acted on, and on 21 November 1860, he asked to be removed from all positions.[57]

Conservative politician

Freed from the demands of his former commissions, Joaquim Inácio spent his time translating Jean-Félicité-Théodore Ortolan's Et Diplomatie De La Mer (The Diplomacy of the Sea) from French into Portuguese.[58][59] He was a cultured person whose penchants included poetry.[45] He was also interested in plays and he was an elected member of the Dramatic Conservatory (which sponsored the national theater) from 8 June 1856.[55] Joaquim Inácio was very religious and he often mentioned God and Catholic saints in his letters.[60][61] During the Paraguayan War in the late 1860s, upon learning that he was being mocked and criticized by the Paraguayans for his religious devotion, Joaquim Inácio merely replied: "Leave me my beliefs and let them call me whatever they want."[62] He was an enthusiastic member of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia (Holy House of Mercy), a charitable organization in Rio de Janeiro. When the national capital was ravaged by yellow fever in 1854, he went from door to door asking for donations to help the sick.[45][61]

Despite his staunch Catholicism, Joaquim Inácio became a freemason, joining the Loja Integridade Maçônica (Freemasonry Integrity Lodge) in 1828.[45] He eventually rose to the highest ranks of that lodge, becoming Deputy Grand Master in 1863.[45] He was also accorded membership in other Brazilian lodges,[45] became an honorary member of Portuguese Freemasonry and was a representative of the Grand Orient de France in Brazil.[63] Freemasonry opened new venues for Joaquim Inácio, providing him with connections and influence he had previously lacked and which were essential to advancing his political career. On 2 March 1861, his friend Caxias, also a freemason and staunch Catholic, became prime minister. He invited Joaquim Inácio, who became a member of the Conservative Party, to assume the naval ministry's portfolio. It was commonplace in Brazil for high-ranking military officers to engage in politics.[58][64]

He served as the first head of the newly created Ministry of Agriculture, Commerce and Public Works from 2 March 1861 until 21 April.[65] Although created by a decree of 1856 (following a suggestion made by Joaquim Inácio in 1851), the first professional firefighter corps in Brazil was effectively formed under his tenure at the head of the Ministry of Agriculture.[53] The cabinet resigned on 24 May 1862 after losing its majority in the Chamber of Deputies (the national legislature's lower house).[45][66] Joaquim Inácio returned to his position on the naval council on 2 July and left that post when he became a member of the Supreme Military and Justice Council on 2 October 1864.[45][67]

Paraguayan War

Commander-in-Chief

In December 1864, the dictator of Paraguay, Francisco Solano López, ordered an invasion of the Brazilian province of Mato Grosso (currently the state of Mato Grosso do Sul), triggering the Paraguayan War. Four months later, Paraguayan troops invaded Argentine territory in preparation for an attack on Rio Grande do Sul. The invasions resulted in an alliance between Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. Following the resignation of Caxias's government in 1862, successor cabinets were headed by the Progressive League, the rival of the Conservative Party. As a Conservative, Joaquim Inácio found himself largely sidelined. He humorously commented that the Progressives "have not lifted my excommunication by giving me a better ration of soup [i.e., any command of importance], thus I shall remain on a diet".[68] In October 1865, Joaquim Inácio was sent to the north of Brazil, charged with recruiting volunteers, but soon resigned that commission and opted to devote his time to the Holy House of Mercy.[69]

The allies invaded Paraguay in April 1866, but their advance by land was blocked by fortifications at Humaitá and naval forces faced the obstacle of entrenched defenses along the Paraguay River. The Progressive cabinet decided to create a unified command over Brazilian land and naval forces operating in Paraguay. It entrusted the command to Caxias, who in turn requested that Joaquim Inácio head the Brazilian fleet in Paraguay.[70] On 22 December, Joaquim Inácio replaced his close friend Vice-Admiral Joaquim Marques Lisboa (then-Baron and later Marquis of Tamandaré) as fleet commander.[70][71] For the sake of appearances, the new position was nominally pro tempore, since Tamandaré had virtually been forced to resign. On 5 February 1867, Joaquim Inácio was promoted to vice-admiral (equivalent to present-day squadron vice-admiral), and sixteen days later he was made permanent commander-in-chief.[70]

The allied objective was to encircle Humaitá and force its capitulation by siege. On 15 August 1867, under heavy fire, Brazilian warships forced the passage of Curupayty, an outer line of defense of Humaitá. Joaquim Inácio commanded from the bridge of the ironclad Brasil, which engaged in the operation.[72] Joaquim Inácio was afterwards awarded the noble title of Barão de Inhaúma (Baron of Inhaúma) on 27 September. The name came from Inhaúma, a region (now a neighborhood) near the city of Rio de Janeiro. His wife had grown up there,[73][74] and he himself owned a coffee farm in the area.[75] Those landowners, including the Baron of Inhaúma, who produced coffee (the most valuable Brazilian export commodity) were the wealthiest and most influential people in Brazil's southeast. They were owners of slaves, and many of them formed the core of the Conservative Party (the ultraconservative wing called saquarema) and were connected to each other through family and political ties.[76]

Operations on the Paraguay River

After Inhaúma had punched through the defenses at Curupayty, he encountered three large chains stretched across the river at Humaitá that prevented further progress upriver beyond the fortress.[77] He anchored his ships in a cove that became known as Porto Elisiário (Elisiário Port).[77] For six months, the Brazilian warships remained stationed between Curupayty and Humaitá, bombarding both strongholds without causing any serious damage.[77] The encirclement of Humaitá could not be completed until the Allies gained full control of the river. The Allied commander-in-chief, Argentine president Bartolomé Mitre, had pressed Inhaúma for months to execute that goal. The Brazilian had, however, developed second thoughts about the enterprise and procrastinated. He believed—unfairly—that Mitre would welcome the destruction of Brazil's warships, severely weakening the Empire militarily and geopolitically.[77]

There were other factors that prompted Inhaúma to have second thoughts. The level of the river had fallen and as the encirclement on land had not been completed, even "if the Brazilian ships did manage to get past the batteries they could well become stranded, with little or no fuel and possibly no supporting Allied troops on the banks".[77][78] Inhaúma also argued that the ironclads were too large and had limited manoeuvrability in the narrow channel at Humaitá, being better suited to seagoing operations than on a river. He preferred to wait for the shallow-draft monitors that were under construction in Rio de Janeiro.[78][79]

After a year in Paraguay, Inhaúma had also become ill with a lingering disease (not positively identified, although malaria is suspected) and had fallen into depression, becoming what historian Francisco Doratioto themed "no more than a ghost of an admiral".[80] By January 1868 Humaitá had been completely cut off from land reinforcement and the shallow-draft monitors had arrived. Both Inhaúma and his officers balked at putting the new vessels into action. It was Inhaúma's son-in-law, Captain of Sea and War Delfim Carlos de Carvalho (soon Baron of Passagem) who volunteered to lead a squadron. On 19 February, the Brazilian ironclads successfully made a passage up the Paraguay River under heavy fire, gaining full control of the river and thus isolating Humaitá from resupply by water.[81][82]

On 2 March 1868, parties of Paraguayans in canoes camouflaged by foliage and brush boarded Brazilian ironclads anchored in Tayí. The imperiled vessels dispatched a boat to warn Inhaúma, who was aboard the flagship Brasil downriver at Elisiário Port. By the time he arrived, the Brazilians had locked themselves inside their ships and the Paraguayans had taken control of the decks. Inhaúma ordered the Brasil and two other vessels to open fire, decimating the Paraguayans and saving the ironclads.[83] A day later he was raised from baron to viscount by Pedro II.[84] On 25 July, the allies occupied Humaitá after the Paraguayans had abandoned it and retreated further upriver.[85]

Illness and death

Unknown to Inhaúma and only a few days before the fall of Humaitá, the Progressive cabinet in Rio de Janeiro had resigned following a political crisis. The Emperor called the Conservatives, under the leadership of Joaquim Rodrigues Torres, Viscount of Itaboraí, back into power on 16 July 1868. During the Progressive administration, Inhaúma had developed a trusting friendship with the able, young Navy Minister Afonso Celso de Assis Figueiredo (later Viscount of Ouro Preto).[86] The return of the Conservatives resulted in Inhaúma's election to the Chamber of Deputies as a representative for the province of Amazonas, although he would never assume office. In the new political climate, Inhaúma was also considered a contender for a senatorial chair representing the province of Rio de Janeiro.[87]

Meanwhile, Caxias had organized an assault on the new Paraguayan defenses which López had thrown up along the Pikysyry, south of Asunción (Paraguay's capital). This stream afforded a strong defensive position which was anchored by the Paraguay River and by the swampy jungle of the Chaco region. Caxias had a road cut through the supposedly impenetrable Chaco, located on the other side of the Paraguayan River where the Allied army was camped. The Brazilian ships carried the Allied troops across the river, where they moved over the road which had been finished in December. The Allied forces outflanked the Paraguayan lines and attacked from the rear. The combined allied forces annihilated the Paraguayan army and on 1 January 1869 Asunción was occupied.[88]

Inhaúma reached the Paraguayan national capital on 3 January 1869,[89] increasingly sick and depressed. He lamented in his private journal that the conflict "cannot be called a war but a killing of people, extermination of the Paraguayan nation".[90] Inhaúma temporarily transferred his command to his son-in-law, the Baron of Passagem, on 16 January.[91][92] On 28 January, Inhaúma was officially discharged from that post and promoted to admiral, the highest rank in the armada.[93][94] Having received permission from the Conservative cabinet to depart, he left for Rio de Janeiro on 8 February,[95] arriving ten days later.[96] Although welcomed "with the greatest demonstrations of enthusiasm",[97] Inhaúma was so weak that he had to be carried from the docks to his carriage. Alfredo d'Escragnolle Taunay, Viscount of Taunay in his memoirs said that Pedro II, upon learning of Inhaúma's arrival, refused to pay a visit to him.[98][99] It had become common for officers to claim sickness so that they could withdraw from the war. The Emperor soon realized that Inhaúma was indeed very ill and asked for daily updates on his condition.[100]

Inhaúma's health steadily deteriorated, and he died on 8 March at around 04:30 in the morning.[100] According to historian Eugênio Vilhena de Morais, malaria was the cause of death.[101] His coffin was placed in a carriage reserved for the funerals of members of the imperial family. It was escorted by three cavalry squadrons and followed by three hundred carriages, while onlookers crowded both sides of the streets along the procession's route.[102] Tamandaré[102] and the future Viscount of Ouro Preto[97] were among the pallbearers. He was buried in the São Francisco Xavier cemetery (popularly known as Caju Cemetery) in Rio de Janeiro.[102]

Legacy

Soon after his death, the Viscount of Inhaúma was hailed as "one of the greatest figures of the Brazilian armada" in the Brazilian Senate.[103] He was extremely popular in the armada and was fondly called "Uncle Joaquim" by his subordinates.[2][104] The Brazilian navy's slang phrase, "andar na Inácia", which meant to behave correctly, was derived from his name.[2] Since 1870, no comprehensive biography of Inhaúma has been published, even though he, according to Francisco Eduardo Alves de Almeira, "is, and always will be, important to the navy of Brazil for his example as a modest and dedicated chief". The Inhaúma-class corvette, built in the 1980s and 1990s, was named after him. Despite the scant attention paid him in historical literature, there are some historians who share a highly positive view of Inhaúma. Américo Jacobina Lacombe said that he was "one of the greatest names in our [Brazilian] military history".[104] Max Justo Guedes regarded him among the greatest imperial navy officers,[105] and Adolfo Lumans considered him one of the greatest navy officers in Brazilian history.[106]

Titles and honors

Titles of nobility

Other titles

- Member of the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute.

- Member of the Supreme Military and Justice Council.[5]

- Provedor interino (interim steward) of the Santa Casa de Misericórdia (Holy House of Mercy) in Rio de Janeiro city.[109][110]

Honors

- Grand Cross of the Brazilian Order of the Rose.[5]

- Grand Cross of the Brazilian Order of Saint Benedict of Aviz.[5]

- Commander of the Brazilian Order of Christ.[5]

- Grand Cross of the Portuguese Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa.[5]

- Grand Officer of the French Légion d'honneur.[5]

Endnotes

- ↑ Joaquim, José and Inácio were all given names. He did not receive the family surname Barros. (Lacombe 1993, p. 57)

- ↑ Bento José de Carvalho would later perish when the corvette Isabel that he commanded sank off the coast of Morocco on 11 November 1860.(Barros 1870, p. 152)(Frota 2008, p. 19)(Lacombe 1993, p. 61)

Footnotes

- ↑ Sisson 1999, p. 387.

- 1 2 3 4 Frota 2008, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Barros 1870, p. 128.

- ↑ Macedo 1876, p. 389.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Haring 1869, p. 57.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, p. 128;

- Sisson 1999, p. 387;

- Frota 2008, p. 16.

- 1 2 Frota 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. IV.

- 1 2 3 4 See:

- Barros 1870, p. 129;

- Sisson 1999, p. 388;

- Frota 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Macedo 1876, p. 390.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 189.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, p. 129;

- Sisson 1999, p. 387;

- Frota 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Sisson 1999, p. 388.

- ↑ Barros 1870, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, pp. 130–131, 139;

- Macedo 1876, p. 390;

- Sisson 1999, p. 388;

- Frota 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, p. 136;

- Sisson 1999, p. 388;

- Frota 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, pp. 135–137;

- Macedo 1876, p. 390;

- Sisson 1999, p. 388;

- Frota 2008, p. 18.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, pp. 146–147;

- Macedo 1876, p. 390;

- Sisson 1999, pp. 388–389;

- Frota 2008, p. 18.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 139.

- 1 2 Frota 2008, p. 18.

- ↑ Barros 1870, pp. 132, 148.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 148.

- ↑ Frota 2008, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, p. 148;

- Sisson 1999, p. 389;

- Frota 2008, p. 19.

- ↑ Frota 2008, p. 19.

- ↑ Barros 1870, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 182.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, pp. 149–150;

- Sisson 1999, p. 389;

- Frota 2008, p. 19.

- ↑ Barros 1870, pp. 150–151.

- 1 2 Sisson 1999, p. 389.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 152.

- ↑ Frota 2008, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Frota 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ Lacombe 1993, p. 61.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, p. 154;

- Andréa 1955, p. 141;

- Frota 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, pp. 154–155;

- Sisson 1999, p. 390;

- Frota 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, p. 157;

- Sisson 1999, pp. 390–391;

- Frota 2008, p. 20.

- 1 2 Barros 1870, p. 158.

- 1 2 3 4 Sisson 1999, p. 391.

- 1 2 Barros 1870, p. 159.

- ↑ Silva 2003, p. 370.

- 1 2 3 4 Frota 2008, p. 21.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, p. 160;

- Sisson 1999, p. 392;

- Frota 2008, p. 21.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 161.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Frota 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Frota 2008, p. 33.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 163.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, p. 168;

- Sisson 1999, p. 392;

- Frota 2008, p. 21.

- ↑ Lacombe 1993, p. 62.

- 1 2 See:

- Barros 1870, p. 169;

- Sisson 1999, p. 392;

- Frota 2008, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 See:

- Barros 1870, p. 169;

- Sisson 1999, p. 393;

- Frota 2008, p. 22;

- Lumans 1943, p. 524

- ↑ Sisson 1999, p. 393.

- 1 2 3 Frota 2008, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Barros 1870, p. 170.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Frota 2008, p. 23.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 171.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, p. 171;

- Sisson 1999, p. 393;

- Frota 2008, p. 23

- Lacombe 1993, p. 63.

- 1 2 Barros 1870, p. 173.

- ↑ Frota 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 157.

- 1 2 Lumans 1943, p. 526.

- ↑ Lacombe 1993, p. 58.

- ↑ Silveira 2003, p. 139.

- ↑ Silva 2003, p. 282.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, p. 173;

- Sisson 1999, p. 394;

- Frota 2008, p. 23.

- ↑ Needell 2006, pp. 215–216.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 177.

- ↑ Frota 2008, p. 25.

- ↑ Frota 2008, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 Frota 2008, p. 28.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 185.

- ↑ See:

- Barros 1870, pp. 227–228;

- Lacombe 1993, pp. 66–67;

- Frota 2008, p. 30.

- ↑ Frota 2008, p. 30.

- ↑ Lumans 1943, p. 530.

- ↑ Lacombe 1993, p. 67.

- ↑ Needell 2006, p. 18, 25, 29, 62.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Doratioto 2002, p. 301.

- 1 2 Hooker 2008, p. 74.

- ↑ Doratioto 2002, pp. 304–308.

- ↑ Doratioto 2002, p. 320.

- ↑ Doratioto 2002, pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Hooker 2008, p. 82.

- ↑ Hooker 2008, p. 83.

- ↑ Frota 2008, p. 38.

- ↑ Doratioto 2002, pp. 329–330.

- ↑ Lacombe 1993, p. 71.

- ↑ Frota 2008, p. 40.

- ↑ Doratioto 2002, p. 384.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 402.

- ↑ Frota 2008, p. 276.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 411.

- ↑ Doratioto 2002, p. 393.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 415.

- 1 2 Frota 2008, p. 41.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 418.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 422.

- 1 2 Ouro Preto 1894, p. 402.

- ↑ Taunay 2004, p. 405.

- ↑ Doratioto 2002, p. 390.

- 1 2 Barros 1870, p. 438.

- ↑ Morais 1958, p. 285.

- 1 2 3 Barros 1870, p. 441.

- ↑ Brazil 1869, p. 76.

- 1 2 Lacombe 1993, p. 57.

- ↑ Guedes 1970, p. 2.

- ↑ Lumans 1943, p. 531.

- ↑ Barros 1870, pp. 156–157.

- 1 2 Lumans 1943, p. 528.

- ↑ Barros 1870, p. 160.

- ↑ Sisson 1999, p. 392.

References

- Andréa, Júlio (1955). A Marinha Brasileira: florões de glórias e de epopéias memoráveis (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Estúdio de Artes Gráficas C. Mendes Júnior.

- Barros, Antônio José Vitorino de (1870). Guerra do Paraguai: O Almirante Visconde de Inhaúma (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Tipografia do Imperial Instituto Artístico.

- Brazil (1869). Anais do Senado do Império do Brasil: primeira sessão em 1869 da décima quarta legislatura de 30 de julho a 30 de agosto (in Portuguese). Vol. 4. Rio de Janeiro: Tipografia do Diário do Rio de Janeiro.

- Doratioto, Francisco (2002). Maldita Guerra: Nova história da Guerra do Paraguai (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 85-359-0224-4.

- Lumans, Adolfo (1943). "O Almirante Visconde de Inhaúma". Anais do Museu Histórico Nacional (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional. 4.

- Frota, Guilherme de Andrea (2008). Diário pessoal do Almirante Visconde de Inhaúma durante a Guerra da Tríplice Aliança (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: G. de Andrea Frota. ISBN 978-85-7204-006-8.

- Guedes, Max Justo (1970). O Reinado de D. Pedro II e a marinha do Brazil (in Portuguese). Petrópolis: Instituto Histórico de Petrópolis.

- Haring, Carlos Guilherme (1869). Almanak Administrativo, Mercantil e Industrial (Almanaque Laemmert) (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Eduardo & Henrique Laemmert.

- Hooker, Terry D. (2008). The Paraguayan War. Nottingham: Foundry Books. ISBN 978-1-901543-15-5.

- Lacombe, Américo Jacobina (1993). Ensaios históricos (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Academia Brasileira de Letras. OCLC 30701799.

- Macedo, Joaquim Manuel de (1876). Ano Biográfico brasileiro (in Portuguese). Vol. 2. Rio de Janeiro: Tipografia e Litografia do Imperial Instituto Artístico.

- Morais, Eugênio Vilhena de (1958). "Ata da sessão comemorativa do sesquicentenário do nascimento do Almirante Joaquim José Inácio, Visconde de Inhaúma". Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional. 241.

- Needell, Jeffrey D. (2006). The Party of Order: the Conservatives, the State, and Slavery in the Brazilian Monarchy, 1831–1871. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5369-2.

- Ouro Preto, Afonso Celso, Viscount of (1894). A Marinha de outrora (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Moderna.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Silva, João Manuel Pereira da (2003). Memórias do meu tempo (in Portuguese). Brasília: Senado Federal.

- Silveira, Mauro César (2003). Adesão fatal: a participação portuguesa na Guerra do Paraguai (in Portuguese). Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS. ISBN 85-7430-374-7.

- Sisson, Sébastien Auguste (1999). Galeria dos brasileiros ilustres (in Portuguese). Vol. 2. Brasília: Senado Federal.

- Taunay, Alfredo d'Escragnolle Taunay, Viscount of (2004). Memórias (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Iluminuras. ISBN 85-7321-220-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

![]() Media related to Joaquim José Inácio, Viscount of Inhaúma at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Joaquim José Inácio, Viscount of Inhaúma at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)