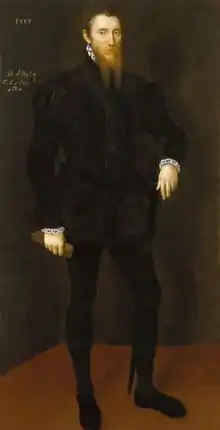

John Astley (ca. 1507 – 1595, Maidstone), also seen as Ashley, was an English courtier, Marian exile, and Master of the Jewel Office. He was a Member of Parliament on many occasions.

Life

He was connected to the Boleyn family through his mother Anne Wood, sister of Elizabeth Boleyn, Lady Boleyn who was married to James Boleyn. His father was Thomas Astley of Hilmorton, Anne being his second wife.

He married in 1545 Katherine Champernowne, later known as Kat Ashley. At this point Katherine was governess to Princess Elizabeth. Astley in Elizabeth's household met Roger Ascham, who became a friend; he prompted Ascham's work A Report of Germany on the Emperor Charles V, and is mentioned as a dinner-party guest in the introductory section of The Scholemaster (1570).[1]

In 1554 he was in Padua.[2] On the accession of Elizabeth he returned to England, and in December 1558 was appointed Master of the Jewel House and Treasurer of Her Majesty's jewels and plate. An inventory of the jewels and plate made by Astley in 1574 has been published.[3] His wife Kat was appointed chief gentlewoman of the privy chamber (she died in 1565), and he was also one of the grooms of the chamber.

He obtained from the crown a grant of the mastership of the game in Enfield Chase and park, with the office of steward and ranger of the manor of Enfield. Accompanying Elizabeth on her visit to the University of Cambridge in 1564, he was created M.A.[4] In or about 1568 the queen granted him a lease in reversion of the castle and manor of Allington, Kent, and he also had an estate at Otterden. He bought Maidstone Palace and had work done to the front of the building.[5] His death appears to have occurred about July 1595. He was aged about 88; he and his wife Margaret are buried in Maidstone church.[6]

In Parliament

He represented various constituencies in the House of Commons:

- Chippenham in 1547.[7]

- West Looe in March 1553.[7]

- St Albans in 1555.[7]

- Cricklade in 1559.[7]

- Boroughbridge in 1563.[8]

- Lyme Regis in 1571 and 1572.[9]

- Maidstone in the parliaments of 29 October 1586 and 4 February 1589.[10]

Works

Astley was the author of a work on horsemanship.[11] It harked back to his days as a Gentleman Pensioner under Henry VIII, and relayed the doctrine of the Italian riding schools, as he and other Gentleman Pensioners had understood it, particularly on training the horse to respond to the hand. Astley was on friendly terms with Thomas Blundeville, whose translation two decades earlier of the Ordini di cavalcare of Federico Grisone was the first treatise on horsemanship to be published in English, and part of which had been dedicated to him.[12] According to Smith, this is the first translation into English of the Ίππική, "On horsemanship", of Xenophon.[13]

Astley may also have been the author of the first English translation of Il cavallerizzo by Claudio Corte, also entitled The Art of Riding,[14] although this is more usually attributed to Thomas Bedingley.

Published works

- The Art of Riding, set foorth in a breefe treatise, with a due interpretation of certeine places alleged out of Xenophon, and Gryson, very expert and excellent horsemen; wherein also the true vse of the hand by the said Grysons rules and precepts is speciallie touched; and how the author of this present worke hath put the same in practise; also what profit men may reape thereby; without the knowledge whereof, all the residue of the art of riding is but vaine. Lastlie, is added a short discourse of the chaine or cauezzan, the trench, and the martingale: written by a gentleman of great skill and long experience in the said art (London: Henrie Denham, 1584)

- (authorship dubious)The Art of Riding, conteining diverse necessary Instruction, Demonstrations, Helps and Corrections, apperteining to Horsemanship, not heretofore expressed by anie other author; written at large in the Italian Toong, by Master Claudio Corte, a man most excellent in this Art. Here brieflie reduced into certeine English Discourses to the benefit of Gentlemen desirous of such knowledge (London, 1584)

- Epistle to Roger Ascham, prefixed to Ascham's The Affairs of Germany in the Reign of the Emperour Charles..., 1552[6]

Family

By his first wife Katherine, daughter of Sir John Champernowne of Devonshire, he had no issue. His second wife was Margaret, daughter of Thomas Lord Grey (a son of Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquess of Dorset),[15][16] by whom he had a son, afterwards Sir John Astley,[17] two other sons, and three daughters.

Notes

- ↑ Lawrence V. Ryan, Roger Ascham (1963), p. 103, p. 156, p. 252.

- ↑ Christina Hallowell Garrett, The Marian Exiles (1938), p. 73.

- ↑ A. Jefferies Collins, Jewels and Plate of Queen Elizabeth I, (British Museum, London, 1955)

- ↑ "Astley or Ashley, John (ASTY564J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ "IB Lending – Financial news and information on borrowing money".

- 1 2 Nichols, John (1797). The Gentleman's magazine, Volume 82. s.n. p. 548.

- 1 2 3 4 "History of Parliament". Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ↑ J. E. Neale, The Elizabethan House of Commons (1963), p. 219.

- ↑ Neale, p. 189.

- ↑ s:Astley, John (d.1595) (DNB00)

- ↑ The Art. of Riding, set foorth in a breefe treatise, with a due interpretation of certeine places alleged out of Xenophon, and Gryson, verie expert and excellent Horssemen, London, 1584.

- ↑ Joan Thirsk, The Rural Economy of England: collected essays (1984), p. 392, and note p. 390.

- ↑ Smith, Sir William (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Ed. by William Smith. Illustrated by numerous engravings on wood. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 1301. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ↑ Watt, Robert (1824). Bibliotheca Britannica, or a general index to British and foreign literature, Volume 1. Constable. p. 51.

- ↑ Lundy, Darryl. "p14824.htm#i148235". The Peerage.

- ↑ Lundy, Darryl. "p14824.htm#i148234". The Peerage.

- ↑ Lundy, Darryl. "p14824.htm#i148233". The Peerage.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Astley, John (d.1595)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Astley, John (d.1595)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.