Sir John Cornwall | |

|---|---|

| Member of the English Parliament for Shropshire | |

| In office 30 September 1402 – 25 November 1402 Serving with Sir Adam Peshale | |

| Preceded by | Sir Hugh Cheyne, John Burley |

| Succeeded by | John Burley, George Hawkestone |

| In office 20 October 1407 – 12 December 1407 Serving with David Holbache | |

| Preceded by | David Holbache, Thomas Whitton |

| Succeeded by | John Burley, David Holbache |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1366 |

| Died | 3 July 1414 (aged 47–48) |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse(s) | Joan Wasteneys of Eastham Maud |

| Children | Elizabeth and Margaret |

| Occupation | Landowner, soldier. |

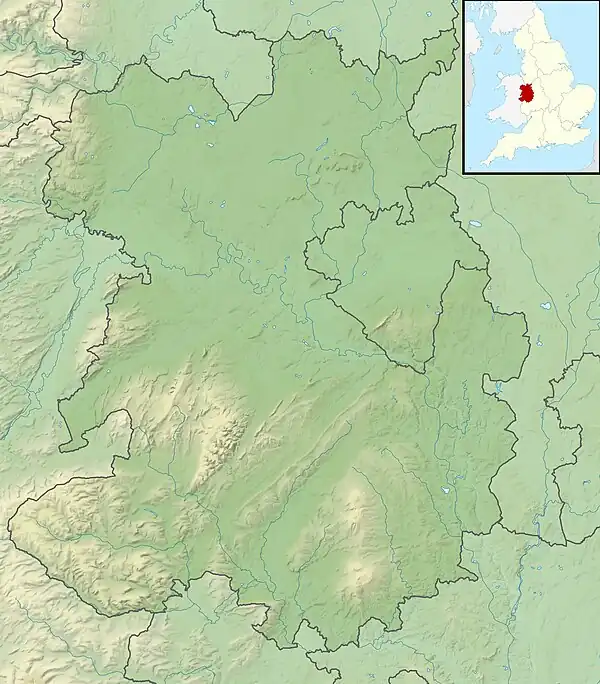

Sir John Cornwall (c.1366–1414) was an English soldier, politician and landowner, who fought in the Hundred Years' War and against the Glyndŵr Rising. He had considerable prestige, claiming royal descent.[1] As he was part of the Lancastrian affinity, the retainers of John of Gaunt, he received considerable royal favour under Henry IV. He represented Shropshire twice in the House of Commons of England. However, he regularly attracted accusations of violence, intimidation and legal chicanery. Towards the end of his life he fell into disfavour and he died while awaiting trial in connection with a murder.

Background

John Cornwall was the son of Brian de Cornwall (died 1391) of Kinlet, Shropshire, second son of Edmund de Cornwall of Thonock, Lincolnshire,[2] and Maud Le Strange, daughter of Fulk, 1st Baron Strange of Blackmere.[3]

Edmund de Cornwall, John's grandfather, was the eldest son of Sir Richard of Cornwall, an illegitimate son of Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall, a very wealthy brother of Henry III who was also for a time King of the Romans.[4] Hence the entire Cornwall line could justly claim descent from King John.[5] Before the Cornwalls, their chief manor of Kinlet had belonged to Brian Brampton,[6] who died late in 1294.[7] His inquisition post mortem[8] revealed a considerable portfolio of estates in the counties of Shropshire and Herefordshire in the Welsh Marches. Edmund took custody of the Brampton estates during the minority of Brian de Brampton's daughters and heiresses, Margaret and Elizabeth, under a grant made by Edward I on 2 January 1305, which called him the "king's yeoman and kinsman".[9][10] However, it seems the grant was only in confirmation, as Cornwall had levied scutage on the Brampton estates in 1300.[11] He acquired Kinlet by marrying Elizabeth, the younger of the two heiresses: she was born on 16 December 1294, probably after her father's death.[12] This Brampton inheritance included other estates, like Ashton in Herefordshire[13] and Idbury in Oxfordshire.[14] Edmund served his cousin the king in the First War of Scottish Independence,[9] perhaps with some distinction and cost to himself, as the fact is mentioned in a royal licence to fell and sell 100 oaks in the Wychwood.[15] After his death in 1354, his estates passed initially to his eldest son, also called Edmund, said variously to be 30 or 40 or more years of age,[16] whose only son predeceased him sine prole.

Brian, as second son, had been recorded as tenant of Idbury, along with Robert Harley, the husband of his aunt Margaret Brampton,[17] as early as 1346.[18] He was granted a collection of Shropshire estates by his mother,[19] and ultimately inherited also those in Herefordshire and Oxfordshire, but not Thonock. He had already proved himself in battle, going to France in 1346 in the retinue of John, 2nd Baron Strange of Blackmere, under the overall command of Richard FitzAlan, 10th Earl of Arundel. There he fought in the Battle of Crécy and the Siege of Calais, winning valuable exemptions from tax and future services.[20] At some point he married John Le Strange's sister, Maud,[21] and John was their eldest surviving son, born around 1366. John had three brothers, Henry, Brian and Thomas, who all died without issue.[3] He also had a sister, Isabel. In 1383 she married John Blount of Sodington,[22] who twice served as MP for Worcestershire.[23]

Landowner

Brian Cornwall died in 1391. The date is variously given as 5 May,[1] and 18 August:[24] the inquisition held at Standlake, Oxfordshire, in early September recorded it as the Friday after the Assumption and stated that John, his heir, was 24 and more years of age – the best evidence for his birth date. It noted that his estates in the county included the manor of Asthall-under-Wychwood, which was held in chief: this was a property that went back to Richard of Cornwall himself, who was granted it in 1227 by his brother, Henry III.[25] There was also Idbury, held of the Earl of March.[26] The inquisition taken at Bridgnorth the following day recorded the manor of Kinlet, also held of the Earl of March, as worth nothing beyond outgoings.[27] It also listed various pieces of land in the vicinity of Kinlet, including a small estate at Catsley. At Leominster an inquisition recorded Brian's moiety of Ashton as held in joint feoffment with his wife Maud, who had survived him.[28] The succession posed few legal issues and on 25 September the escheators were ordered to hand over to John Cornwall all his lands held in chief.[29]

Three years earlier, John had agreed to allow his mother two thirds of Ashton for her lifetime, which was over and above her dower.[30] Maud had omitted to present her proofs of ownership at Idbury and the inquest had left open the question of the terms on which it was held. In November the king, Richard II, gave her extra time to complete the formalities, promising not to penalise the escheator for the resulting deficient accounts.[31] As Ashton was not held in chief but of the Earl of March, the king gave orders on 8 February 1392 to have it released to Maud without delay.[32] The whole question of Maud's dower now appeared settled, with the escheator of Oxfordshire ordered to take her oath and release the property on 30 April, and his counterpart in Shropshire simply to assign the dower.[33] However, further delays did actually occur, perhaps as a result of the handover to a new escheator in Oxfordshire, who was ordered to meddle no further with the Idbury estate in May 1393.[34] In addition to the lands revealed by the inquisitions, John Cornwall inherited small estates close to the Welsh border, including a moiety of Worthen,[1] which had been listed among Edmund Cornwall's holdings and took in an area of the Forest of Caus.[16]

Although he inherited several estates, John Cornwall was not left with great wealth. His mother took the proceeds of well over a third of the estates while she lived. Moreover, Kinlet, the Shropshire seat seems to have been especially unprofitable, producing no surplus. Cornwall did not even acquire the advowson of Kinlet church with the lordship: it was held[35] and exercised by the abbot and convent of Wigmore Abbey.[36] The dire situation here was not unusual, as 14th century had been a time of great suffering in the countryside, with a major agrarian crisis in 1315-22[37] and the onset of the Black Death in 1349.[38] In the worst times, Shropshire inquisitions declared estates worthless or nearly so,[39] and landowners sometimes struggle to meet even modest rents,[40] mainly because it was hard to find tenants or labour in the depopulated countryside, although this placed the survivors in an advantageous bargaining position. Landlords tended to suffer from the falling value of their estates until at least the 1370s[41] but there was then an upturn and the last decades of the century were a time of growing, if modest, prosperity.

Cornwall also acquired control of the manor of Eastham, Worcestershire by marriage to Joan Wasteneys or Westneys.[42] Before Joan's father, Sir William Wasteneys there had been a fairly rapid succession of manorial lords at Eastham, where the advowson belonged to the lord of the manor,[43] allowing a succession to be traced through the details of presentations to the rectory in the episcopal registers. In June 1349, just after the onset of the Black Death, it was Thomas de Doverdale who presented to the church[44] but in May 1357 it was Joan de Carru.[45] In 1361, a peak plague year, John de la More and John Fyman, chaplain, were described as "lords of Eastham" when presenting William de la More to the church.[46] Walter Hewet, grandfather of Cornwall's wife, appears in 1368, alongside the priest William de la More, among a group who obtained a licence to enlarge their park at Eastham by 300 acres.[47] By 1381 Sir William Wasteneys was in charge, approving an exchange of clergy.[48] However, another exchange took place on 28 October 1395.[49] and this time the patron was not Sir William, but his wife Dame Alice.[50] Not until January 1405 does Sir John Cornwall appear as the patron, jointly with his son-in-law William Lichfield and chaplain John Leye.[51] It seems that he had to wait some time before effective control at Eastham. Moreover, the value of the manor was not high, given as just 20 marks in a Chancery inquisition of 1431 after the death of Roger Corbet, who married Cornwall's granddaughter.[52] During Cornwall's time Eastham was held of Richard Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick.

Political and military career

Active service and royal favour

Cornwall formally entered the Lancastrian affinity on 12 March 1395 at Saint-Seurin in Bordeaux through an indenture with John of Gaunt.[53] This was at a time of truce in the Hundred Years' War, with Richard II's effective power confined to very small enclaves along the west coast of France. Cornwall was still an esquire and the indenture is unusual in giving him both wages and bouche of court – a privilege reserved for knights.[54] He promised to serve Gaunt tant en temps de pees come de guerre al terme de sa vie – alike in times of peace and war to the end of his life. He was bound to turn out for war mounted and arrayed in a way suitied to his station in life. In return he was assigned an annuity of 20 marks, drawn from the revenues of the manor of Aldbourne in Wiltshire.[55] The payment would rise to £20 when he was knighted.

Simon Walker's study of the Lancastrian affinity lists Cornwall as plain John, beneath Sir John Cornwall, also a long-serving member of Gaunt's retinue who received the £20 appropriate to a knight.[56] Cornwall of Kinlet is recorded as receiving his 20 marks up to 1399. On 9 June 1397 John Cornewale, knight, was listed as one of those granted royal protection for the expedition to Ireland, commanded by Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, the king's Lieutenant.[57] Mortimer was overlord at Kinlet and Ashton, and medieval records are fairly imprecise about knightly status, which makes it quite probable this Cornwall was the subject of this article. However, there is a strong possibility that it was actually his namesake, who later became Baron Fanhope.

As an established part of the Lancastrian affinity, Cornwall benefited from the overthrow of Richard II in 1399 and was in immediately in favour with Henry IV. He was knighted and was made Sheriff of Shropshire on the first day of the new reign. His annuity was also confirmed. However, his good standing with the new régime was soon threatened by allegations of criminality.

Withiford rustling case

Cornwall was accused of cattle rustling at Wytheford (also rendered Withiford) in Shropshire in April 1401.[58] Cornwall claimed, through his attorney, that he had been acting on behalf of John de Knyghteley. In support of this he offered a long and complex supporting narrative, starting with the death of Thomas de Charlton, who had held the estate until 1388, and whose heirs were minors.[59] The king had sold their marriages and the custody of their estates to speculators, who in turn sold them to Knyghteley. However, the custody had itself now descended to a minor, and Cornwall claimed to be acting in his interests to reclaim arrears. The case affected the king's interests, as the plaintiffs, who were demanding £100, alleged that their cattle had already been taken into the custody of the county escheator when Cornwall removed them.[60] By the time the case came up for trial in 1402, John Darras was Sheriff of Shropshire.[61] Darras could be relied upon to assist Cornwall as he was both a personal friend and had been married to Joan Corbet, his first cousin. In April 1402 he was one of four local gentry who made mainprise (essentially similar to bail) at Westminster for Cornwall that he would keep the peace,[62] creating a conflict of interest. The case was moved to the Shrewsbury assizes by a writ of nisi prius and there the plaintiffs claimed that Darras had allowed Cornwall to nominate the panel of jurors.[60] Consequently, the jury was dismissed, the case adjourned, and Darras ordered to summon new jurors for the next assizes. Darras was also the returning officer when Cornwall was elected to Parliament.[61]

Member of Parliament, 1402

Cornwall was returned as a Member of the House of Commons of England, with Sir Adam de Peshale. During the course of the parliament he accused Maud Copel, also known as Knyton, of being a spy for Owain Glyndŵr, leader of the Welsh rebellion. Maud was imprisoned on his accusation but doubts seem to have arisen fairly quickly and on 17 October the king ordered her release, on the grounds that there were credible witnesses to the contrary.[63]

The Welsh rebellion

The Glyndŵr Rising now loomed large in Cornwall's career. In September 1403 he was ordered by the king to garrison and to hold Manorbier Castle. Presumably he did this efficiently as he was next given a major organisational task. Instructions given to Cornwall, John Burley and Thomas Young, at the Parliament of 1404, which took place in Coventry, but they were embodied in a formal commission on 24 March 1405.[64] They were to supervise the musters of troops in Shropshire and Cheshire and to report back on numbers, as Prince Henry had been appointed the king's lieutenant in North Wales and needed 500 men-at-arms and up to 3000 archers for a punitive expedition.

Both of Cornwall's collaborators, Burley[65] and Young[66] were key members of the Arundel affinity. The FitzAlan earls of Arundel were the richest and most important landowners in Shropshire,[67] and had long been so. Richard II had executed Richard FitzAlan, 11th Earl of Arundel, one of the Lords Appellant, in 1397. His brother, Archbishop Thomas Arundel, and his dispossessed son, Thomas FitzAlan, 12th Earl of Arundel, were supporters of Henry IV in his bid for power. The restored young earl dominated the politics and parliamentary representation of Shropshire through his extensive network of retainers,[68] which included soldiers, landowners, lawyers and clerics. Cornwall's friend John Darras was a member of the Arundel affinity, valued by the earl and the king for his service in Wales.[61] Arundel himself was closely involved in mobilising and commanding troops for the Welsh campaigns. On 7 October 1405, Cornwall, Burley and Roger Haldenby, a cleric, were commissioned to raise troops for him to garrison castles in North Wales and Shropshire.[69] On the same day Cornwall, Arundel and Burley were issued a commission of oyer and terminer to hunt down people in Shropshire who were secretly supplying the rebels. In January 1406 Prince Henry was commissioned to extend his operations to South Wales, while Cornwall, Burley and Haldenby were commissioned to raise further troops in the Welsh Marches.[70] In June of that year, perhaps in connection with the campaigns and investigations, the king issued a pardon to one of Cornwall's servants from Worcestershire.[71]

Member of Parliament, 1407

Cornwall was knight of the shire for Shropshire again in 1407, returned alongside David Holbache, a man of Welsh origins, a close aide and lawyer to Arundel.[72]

Keeper of Morfe and Shirlett

Cornwall's friend, John Darras hanged himself at his own manor of Neenton in 1408, the first notice of the suicide being a commission from the king, issued on 30 March, to four Shropshire gentry to investigate possible concealment of the deceased's goods.[73] Darras had been keeper of Morfe and Shirlett, areas of Royal forest on either side of the Severn in Shropshire, a post his he held in recognition of his military service in the Welsh campaigns.[74] Soon after his suicide, on 2 April, the king conferred the office on Cornwall, described as a "king's knight."[75] The grant made clear the value of the appointment, "with all wages, fees, profits and commodities as John Darras, deceased, had while he lived." This was a rectification of previous confusion, as the keepership seems to have been promised to one Nicholas Gerard. Cornwall seems to have been a trusted man at this point, as on 5 April he and Burley were among those commissioned to investigate a murder in Shropshire.[76] Such judicial tasks continued, with Cornwall delivering writs and making arrests for the king.[77]

However, Cornwall proved himself overbearing and vexatious in office. In March 1410 the king ordered Arundel and his legal team, John Burley, David Holbache and Thomas Young, with the addition of Lord Furnival, one of Arundel's rivals, to investigate breaches of customary manorial and grazing rights at Worfield in Morff Forest,[78] made by Arundel's brother-in-law, William de Beauchamp, 1st Baron Bergavenny. Beauchamp's complaint did not cite Cornwall by name but mentioned only "certain evildoers." He alleged he had been hindered in his view of frankpledge and in holding his biannual court leet and that both he and his tenants were not able freely to enjoy their customary common pasture, both within and without the royal forest. It was reckless of Cornwall to challenge a man so powerful on his own account and so closely connected to Arundel. However, there had been similar complaints from William Ferrers, 5th Baron Ferrers of Groby. Clearly Cornwall was not deterred by aristocratic and royal concern, as Joan Beauchamp, Arundel's sister made an almost identical complain about Cornwall in late 1411 or early 1412, after she was widowed,[79] and the same team was once again commissioned to investigate. The following year the king received a complaint from John Marshall, Dean of his royal free chapel at Bridgnorth, this time naming Cornwall clearly as the culprit.[80] Marshall alleged that he and the king's tenants at Claverley were being forced to pay an annual fine to access their time-honoured common grazing for sheep, pigs and other animals. Even before sending in Arundel's lawyers to investigate, the king secured Cornwall's resignation and on 13 February 1413 installed Roger Willey, Darras's old business partner, as keeper of Morfe and Shirlett in his place.[81]

Murder charge and death

In April 1413 a group of Midlands gentry, led by William Lichfield, Cornwall's son-in-law, made mainprise of £100 for him at Westminster and he undertook, under a pain of £500, to do no harm to anyone. This was a prelude to a case tried at Court of King's Bench at Shrewsbury in Trinity term. Henry V was present in person,[82] along with William Hankford, the Chief Justice of the King's Bench, in response to complaints about the prevalence of bad governance and murder in Shropshire made at the Fire and Faggot Parliament in Leicester, earlier that year.[68] The business was dominated by the aftermath of large-scale violence between the Arundel affinity and the followers of Lord Furnival in 1413. However, Cornwall was accused of procuring Henry Cornwall of Catsley, possibly his own illegitimate son,[1] to commit a murder and of harbouring him after the event.[83] Henry seems to have had a reputation for violence, as he was also accused of a serious assault on a cleric in 1412. The murder had taken place in August 1413 at Sir John Cornwall's own manorial court in Kinlet, emphasising the likelihood of his complicity.

Before the case against him could proceed further, Cornwall died on the Thursday after the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul,[22] which was 3 July 1414.[84]

Family

Marriages

Sir John Cornwall is known to have married twice By 1390 Cornwall had married Joan Wasteneys, the daughter of

- Sir William Wasteneys of Eastham

- Alice, daughter of Walter Hewet.

The marriage seems to have produced two daughters, although only Elizabeth was involved in the succession.

Cornwall's first wife seems to have died after a few years and by 1397 he had a second wife called Maud.

Succession

An inquisition at Much Wenlock on 23 September 1414, recording his Shropshire lands as consisting of only an acre at Great Meaton. It is possible he had already settled his estates on his successors, giving the reversion of the Shropshire estates to his sister's family.[85] The inquisition also recognised that the heir to Cornwall's estates was his daughter Elizabeth, about 24 years of age at Sir John's death.[84] She had married William Lichfield, who took his name from the cathedral town of Lichfield in Staffordshire and became wealthy through both marriage and inheritance.

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Roskell, J.S.; Woodger, L.S. (1993). "CORNWALL, Sir John (c.1366–1414), of Kinlet, Salop.". In Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Members. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ↑ Blakeway, p. 84-5.

- 1 2 Blakeway, p. 115-6.

- ↑ Marshall, p. 225-6

- ↑ Blakeway, p. 114.

- ↑ Feudal Aids, volume 4, p. 246.

- ↑ Eyton. Antiquities of Shropshire, volume 4, p. 252.

- ↑ Inquisitions Post Mortem, volume 3, p. 189-90, nos. 290-1.

- 1 2 Foljambe and Reade, p. 56. This source gives the year as 1304, presumably adopting Old Style.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1301–1307, p. 308.

- ↑ Eyton. Antiquities of Shropshire, volume 4, p. 254.

- ↑ Eyton. Antiquities of Shropshire, volume 4, p. 244.

- ↑ Feudal Aids, volume 2, p. 328.

- ↑ Feudal Aids, volume 4, p. 160. and p. 164.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1301–1307, p. 461.

- 1 2 Inquisitions Post Mortem, volume 10, p. 138-9, no. 158.

- ↑ Foljambe and Reade, p. 57.

- ↑ p. 184.

- ↑ Foljambe and Reade, p. 65.

- ↑ Le Strange, p. 314-5.

- ↑ Foljambe and Reade, p. 66.

- 1 2 Marshall, p. 229

- ↑ Woodger, L.S. (1993). "BLOUNT, John II (aft.1345-1425), of Sodington, Worcs.". In Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Members. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ↑ Blakeway, p. 116.

- ↑ Rotuli Litterarum Clausarum In Turri Londinensi Asservati, volume 2, p. 198.

- ↑ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, volume 16, no. 1102.

- ↑ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, volume 16, no. 1103.

- ↑ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, volume 16, no. 1104.

- ↑ Calendar of Fine Rolls, 1391–1399, p. 14.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1385–1389, p. 622.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1389–1392, p. 510.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1389–1392, p. 443.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1389–1392, p. 460.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1392–1396, p. 60.

- ↑ Eyton. Antiquities of Shropshire, volume 4, p. 255.

- ↑ Registrum Roberti Mascall, p. 183.

- ↑ D. C. Cox; J. R. Edwards; R. C. Hill; Ann J Kettle; R. Perren; Trevor Rowley; P. A. Stamper (1989). "Domesday Book: 1300-1540". In Baugh, G. C.; Elrington, C. R. (eds.). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 4., note anchor 4.

- ↑ D. C. Cox; J. R. Edwards; R. C. Hill; Ann J Kettle; R. Perren; Trevor Rowley; P. A. Stamper (1989). "Domesday Book: 1300-1540". In Baugh, G. C.; Elrington, C. R. (eds.). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 4., note anchor 13.

- ↑ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, Edward III, Volume 11, File 179, no. 537.

- ↑ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, Edward III, Volume 11, File 166, no. 233.

- ↑ D. C. Cox; J. R. Edwards; R. C. Hill; Ann J Kettle; R. Perren; Trevor Rowley; P. A. Stamper (1989). "Domesday Book: 1300-1540". In Baugh, G. C.; Elrington, C. R. (eds.). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 4., note anchor 26.

- ↑ Page, William Henry; Willis-Bund, John William, eds. (1924). "Parishes: Eastham". A History of the County of Worcester., note anchor 41.

- ↑ Page, William Henry; Willis-Bund, John William, eds. (1924). "Parishes: Eastham". A History of the County of Worcester., note anchor 131.

- ↑ Registrum Johanis de Trillek, p. 176.

- ↑ Registrum Johanis de Trillek, p. 189.

- ↑ Registrum Ludowici de Charltone, p. 63.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1364–1367, p. 295.

- ↑ Registrum Johannis Gilbert, p. 123.

- ↑ Registrum Johannis Trefnant, p. 189.

- ↑ Registrum Johannis Trefnant, p. 180.

- ↑ Registrum Roberti Mascall, p. 170.

- ↑ E-CIPM 23-489: Roger Corbet, Esquire at Mapping the Medieval Countryside.

- ↑ Walker, p. 299.

- ↑ Walker, p. 293.

- ↑ Walker, p. 300.

- ↑ Walker, p. 267.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1396–1399, p. 146.

- ↑ Wrottesley (1894), p. 102.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1385–1389, p. 484.

- 1 2 Wrottesley (1894), p. 103.

- 1 2 3 Woodger, L. S. (1993). "DARRAS, John (c.1355–1408), of Sidbury and Neenton, Salop.". In Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Members. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1399–1402, p. 555.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1402–1405, p. 20.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 6.

- ↑ Woodger, L. S. (1993). "BURLEY, John I (d.1415/16), of Broncroft in Corvedale, Salop.". In Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Members. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Woodger, L. S. (1993). "YOUNG, (YONGE), Thomas I, of Sibdon Carwood, Salop.". In Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Members. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ D. C. Cox; J. R. Edwards; R. C. Hill; Ann J Kettle; R. Perren; Trevor Rowley; P. A. Stamper (1989). "Domesday Book: 1300-1540". In Baugh, G. C.; Elrington, C. R. (eds.). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 4., note anchor 46.

- 1 2 Woodger, L. S. (1993). "Shropshire". In Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Constituencies. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 147.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 156.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 183.

- ↑ Woodger, L. S. (1993). "HOLBACHE, David (d.c.1422), of Dudleston and Oswestry, Salop.". In Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Members. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 485.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 296.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 424.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 474.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 66.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 182.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 377.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 477.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 465.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 390.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 393.

- 1 2 Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, Henry V, volume 20, no. 253: C 138/10, no. 45.

- ↑ Blakeway, p. 117.

References

- Blakeway, John Brickdale (1908). "Notes on Kinlet". In Baldwyn Childe, Frances C. (ed.). Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. 3. Vol. 8. Shrewsbury: Adnitt and Naunton. pp. 83–150. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Capes, William W., ed. (1916). Registrum Johannis Trefnant, Episcopi Herefordensis. Vol. 20. London: Canterbury and York Society. Retrieved 10 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Christina Colvin; Carol Cragoe; Veronica Ortenberg; R B Peberdy; Nesta Selwyn; Elizabeth Williamson (2006). "Asthall: Manors and other estates". In Townley, Simon (ed.). A History of the County of Oxford. Vol. 15. London: British History Online. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Corbet, Augusta Elizabeth Brickdale. The Family of Corbet; its Life and Times. Vol. 2. London: St. Catherine Press. Retrieved 3 October 2013. at Internet Archive.

- D. C. Cox; J. R. Edwards; R. C. Hill; Ann J Kettle; R. Perren; Trevor Rowley; P. A. Stamper (1989). "Domesday Book: 1300-1540". In Baugh, G. C.; Elrington, C. R. (eds.). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 4. London: British History Online. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Dawes, M.C.B., ed. (1935). Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem: Edward III. Vol. 11. London: HMSO. Retrieved 8 July 2016. at British History Online.

- M. C. B. Dawes; M. R. Devine; H. E. Jones; M. J. Post, eds. (1974). Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem: Richard II. Vol. 16. London: HMSO. Retrieved 7 July 2016. at British History Online.

- Eyton, Robert William (1857). Antiquities of Shropshire. Vol. 4. London: John Russel Smith. Retrieved 7 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Fletcher, W. G. D., ed. (1907). "Some proceedings at the Shropshire Assizes, 1414". Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. 3. Vol. 7. Shrewsbury: Adnitt and Naunton. pp. 390–396. Retrieved 12 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Foljambe, Cecil G. S.; Reade, Compton (1908). The House of Cornewall. Hereford: Jakeman and Carver. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Hardy, Thomas Duffus, ed. (1844). Rotuli Litterarum Clausarum In Turri Londinensi Asservati. Vol. 2. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode. Retrieved 13 July 2016. at Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Digitale Bibliothek.

- Kirby, J. L., ed. (1995). Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem: Henry V. Vol. 20. London: HMSO. Retrieved 13 July 2016. at British History Online.

- Leland, John (1770). Hearne, Thomas (ed.). De Rebus Britannicis Collectanea. Vol. 1. London. Retrieved 16 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- "Mapping the Medieval Countryside". University of Winchester/King's College London. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- Marshall, George William (1879). "The Barons of Burford". The Genealogist. Vol. 3. London: George Hill. pp. 225–230. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1912). Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem: Edward I. Vol. 3. London: HMSO. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Internet Archive .

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1921). Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem: Edward III. Vol. 10. London: HMSO. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1921). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1385–1389. Vol. 3. London: HMSO. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1922). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1389–1392. Vol. 4. London: HMSO. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1925). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1392–1399. Vol. 5. London: HMSO. Retrieved 8 July 2016. at Brigham Young University.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1927). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1399–1402. Vol. 1. London: HMSO. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1929). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1402–1405. Calendar of close rolls : Henry IV. Vol. 2. London: HMSO. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1929). Calendar of the Fine Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1391–1399. Vol. 11. London: HMSO. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1898). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward I, 1301–1307. London: HMSO. Retrieved 7 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1912). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward III, 1364–1367. Vol. 13. London: HMSO. Retrieved 10 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1900). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1385–1389. Vol. 3. London: HMSO. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1909). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1396–1399. Vol. 6. London: HMSO. Retrieved 11 July 2016. at Brigham Young University.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1907). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1405–1408. Vol. 3. London: HMSO. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1909). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1408–1413. Vol. 4. London: HMSO. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1900). Inquisitions and Assessments relating to Feudal Aids, A.D. 1284-1431. Vol. 2. London: HMSO. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1906). Inquisitions and Assessments relating to Feudal Aids, A.D. 1284-1431. Vol. 4. London: HMSO. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1908). Inquisitions and Assessments relating to Feudal Aids, A.D. 1284-1431. Vol. 5. London: HMSO. Retrieved 6 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Page, William Henry; Willis-Bund, John William, eds. (1924). "Parishes: Eastham". A History of the County of Worcester. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 8 July 2016. at British History Online

- Parry, Joseph Henry, ed. (1912). "Registrum Johanis de Trillek, Episcopi Herefordensis". Canterbury and York Series. Vol. 8. London: Canterbury and York Society. Retrieved 10 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Parry, Joseph Henry, ed. (1914). "Registrum Ludowici de Charltone, Episcopi Herefordensis". Canterbury and York Series. Vol. 14. London: Canterbury and York Society. Retrieved 10 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Parry, Joseph Henry, ed. (1915). Registrum Johannis Gilbert, Episcopi Herefordensis. Vol. 18. London: Canterbury and York Society. Retrieved 10 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Parry, Joseph Henry, ed. (1918). Registrum Robert Mascall, Episcopi Herefordensis. Vol. 21. London: Canterbury and York Society. Retrieved 10 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Roskell, J. S.; Clark, L.; Rawcliffe, C., eds. (1993). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Constituencies. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L., eds. (1993). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Members. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Le Strange, Hamon (1916). Le Strange Records. London: Longman, Green. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Walker, Simon (1990). The Lancastrian Affinity 1361–1399. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820174-5.

- Wrottesley, George, ed. (1894). "Extracts from the Plea Rolls, 1387–1405". Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 15. London: Harrison. pp. 1–126. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Wrottesley, George, ed. (1896). "Extracts from the Plea Rolls of the Reigns of Henry V and Henry VI". Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Vol. 17. London: Harrison. pp. 1–153. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- Wrottesley, George, ed. (1905). Pedigrees from the Plea Rolls. London: Public Record Office. Retrieved 12 July 2016.