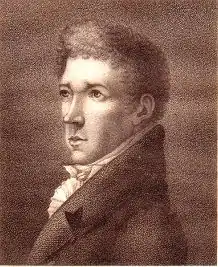

John DeWolf | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Born | October 6, 1779 |

| Died | March 8, 1872 (aged 92) |

| Resting place | Forest Hills Cemetery, Jamaica Plain, Boston |

| Other names | John D'Wolf |

| Occupation(s) | Maritime fur trader, sea captain, and businessman |

| Known for | Maritime fur trade, Russian-American Company, uncle of Herman Melville |

| Notable work | A Voyage to the North Pacific and a Journey Through Siberia: More Than Half a Century Ago |

| Spouse | Mary Melville |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame |

John DeWolf (6 September 1779 - 6 March 1872), also known as John D'Wolf, John D'Wolfe, John DeWolfe, John DeWolf II, Norwest John or Nor'west John, was a sea captain, merchant, and businessman known for his role in the maritime fur trade in the Pacific Northwest, and his influence on the Russian-American Company in Novo-Arkhangelsk (today Sitka, Alaska) in Russian America, and for being an uncle of Herman Melville. Melville was inspired by DeWolf's stories, including an encounter with a large whale that contributed to Melville's Moby-Dick, which Melville describes explicitly in Moby Dick, "Chapter XLV: The Affidavit".[1] "Captain D'Wolf" is also described in the same chapter.[2] John DeWolf was the first American known to have travelled overland across Siberia,[3] and probably the first person ever to circumnavigate the globe by way of crossing Asia overland.[4][5]

Early life

John DeWolf was born in Bristol, Rhode Island, the only child of Simon DeWolf and Hannah May, Simon having died in 1779 at age 26. John was part of the prominent DeWolf family of Rhode Island, which had become wealthy through the Atlantic slave trade, starting with DeWolf's grandfather Mark Anthony DeWolf. The DeWolf family had a major influence on Bristol during the early United States era. The family dominated Bristol shipping, slaving, banking, trading, and politics from the late 18th century through the early 19th century. DeWolf lived through the family's mid-19th century shift from maritime commerce to industry in Bristol.[6]

DeWolf went to sea at a young age, participating in his family's slave trading business. He wrote that he disliked the slave trade and wished to end his involvement in it by trying his luck in the maritime fur trade, which involved trading with the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast for sea otter furs, which commanded a high price in China.[7] At the same time, about 1800, James DeWolf, the elder patriarch of the DeWolf family and John's uncle, began working to diversify the DeWolf family business, due to increasing restrictions on the slave trade. The maritime fur trade was booming around 1800 and the DeWolf family was well positioned to join in the trade. At least one maritime fur trading expedition was conducted by the DeWolf family from 1801 to 1804. This voyage, done with one of the DeWolf family's ships, Juno, under Captain Jabez Gibbs, returned to New England in 1804.[8]

DeWolf also returned to New England in 1804, after a long voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, on what was probably a slave trading venture. Shortly after DeWolf's return the Juno was re-registered with George and John DeWolf as the primary owners, in preparation for the Juno being sent on another maritime fur trading venture, this time with DeWolf as captain.[8]

The Juno

In 1799, shipwrights in Dighton, Massachusetts, completed construction of the ship Juno. According to ship registries in Rhode Island, where the Juno was registered in 1800, she measured 82.5 ft (25.1 m) long, 24 ft (7.3 m) wide, and 12 ft (3.7 m) deep, and could displace up to 295 tons burden fully loaded.[9] A three-masted ship with two decks, the Juno was a fast sailing merchant vessel that had a sharp keel lined with copper. Records say that she was fitted with a female figurehead on the bow, likely a representation of her Roman namesake. She was armed with eight cannons. Her shape and guns gave Juno what DeWolf called a “formidable and warlike appearance.”[9]

Juno was taken to the Pacific Northwest on a maritime fur trading venture from 1802 to 1804, under Captain Jabez Gibbs. This voyage was not well documented and little is known about it. As during the second voyage under John DeWolf, at times Juno sailed in company with Mary, another maritime fur trading ship, based out of Boston and under the command of Captain William Bowles during the first voyage, and Captain Trescott during the second. On the first voyage, Mary and Juno unsuccessfully attempted to rescue the survivors of the Boston at Nootka Sound. Earlier in 1803 the Boston, under John Salter, had been captured by Chief Maquinna. The two survivors, John Thompson and John R. Jewitt, lived as Maquinna's slaves. Their plight was well known to other trading ships. They were eventually rescued in July 1805 by Captain Samuel Hill of the trading ship Lydia.[8]

After the return of the Juno in 1804 the ship was re-registered by John DeWolf's uncles James and Charles DeWolf, his cousin George DeWolf, and John DeWolf himself. John and George were the primary owners. The DeWolf family had owned the Juno since its construction in 1799, and several other ships named Juno as well.[8]

Voyage to the Pacific Northwest and Siberia

John DeWolf acquired partial ownership of Juno and, at age 24 was made captain and supercargo and provided with a crew of 26 men and boys. After preparing the ship for the long voyage, including a large cargo of trade goods including hardware, rum, tobacco, beads, dried beef, firearms, and cottons,[10] intended for both the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast and the Russians of Russian Alaska, DeWolf left Rhode Island on 13 August 1804.[11] He passed Cape Verde on 20 September. On 9 October crossed the equator and soon was near Rio de Janeiro.[12]

On 13 November 1804 Juno fell in with the Mary, another maritime fur trading vessel heading for the Pacific Northwest under Captain Trescott of Boston. Sailing together the two ships passed the Falkland Islands in mid-November, then prepared to round Cape Horn. They experienced rough seas and gale force winds. On 19 November 1804 the Juno and Mary collided during a storm. They suffered damage of various kinds, especially to their rigging, but were able to continue on after getting untangled. The ships lost sight of each other for most of the rest of December.[12]

By 10 December 1804 DeWolf judged that Juno was northwest of Cape Horn and the worst of the danger was over. He decided to stop in Spanish Chile for much needed repairs. Captain Trescott of Mary did not want to stop, so the ships parted company on 29 December 1805. DeWolf approached Concepción, stopped briefly at Valparaíso, then stayed at Coquimbo from 20 to 28 January 1805. With Juno substantially repaired, DeWolf then sailed to the Pacific Northwest Coast.[12]

On 7 April 1805 DeWolf reached the maritime fur trading site Nahwitti, at the north end of Vancouver Island. He found the Mary already there, along with another trading ship named Pearl, under John Ebbets, who helped pilot Juno into the harbor. DeWolf found trading with the indigenous peoples at Nahwitti, mostly Kwakwakaʼwakw, difficult. By 1805 sea otters populations had been greatly reduced and the prices demanded were mostly too high for DeWolf. On 20 April 1805 he set sail for the more northernly trading site of Kaigani. Some trading stops were made along the way. DeWolf arrived at Kaigani in late April 1805 and found two trading ships present. They were the Vancouver, under Thomas Brown, and the Caroline, under William Sturgis. DeWolf had the damaged mizzenmast of Juno replaced. The local Haida peoples offering sea otter furs for sale, but as at Nahwitti DeWolf found the prices too high.[8]

In May 1805 DeWolf left Kaigani and sailed north to the Russian-American Company (RAC) outpost at Novo-Arkhangelsk, today Sitka, Alaska. The outpost had only been taken from the indigenous Kiks.ádi Tlingit less than a year prior, after the Battle of Sitka, the culmination of Russian–Tlingit conflict at Sitka since 1799. Instrumental in the Russian victory over the Tlingit was the timely arrival of the warship Neva, under Yuri Lisyansky, Lieutenant commander of the Imperial Russian Navy. After the battle the surviving Tlingit moved northeast in a migration known as the "Survival March". They resettled in the region around where Peril Strait connects with Chatham Strait, especially in the vicinity of Point Craven.[8]

When DeWolf arrived, the RAC Chief Manager Alexander Baranov, having driven away the Kiks.ádi Tlingit, was in Sitka. An American working for the RAC, Abraham Jones, introduced DeWolf and Baranov. The two got along well. DeWolf was impressed with Baranov and his friendly hospitality.[8]

After successfully trading some goods with the Russians at Sitka, DeWolf sailed Juno south, stopping at many places to trade with the indigenous peoples. In late June 1805 DeWolf arrived at Nahwitti once again. He found five trading vessels in the harbor. The Mary and Pearl, and three vessels owned by the Lyman family of Boston—Lydia, under Samuel Hill, Vancouver, under Thomas Brown, and Atahualpa. The Atahualpa had just suffered a violent clash with the Heiltsuk people (Q̓vúqvay̓áitx̌v) in Milbanke Sound,[13] resulting in the death of the captain, first mate, second mate, supercargo, cooper, cook, and many seamen. The various ships were working to transfer crew members and cargos and make repairs so that the Atahualpa could sail to China and then New England. DeWolf assisted in the effort.[8]

In mid-July 1805 DeWolf left Nahwitti to cruise the coast northward again. On 27 July 1805 he reached Chatham Strait and met a large group of Tlingit. The Tlingit invited Juno to anchor for trade, but in a way that made DeWolf suspicious and wary to the point where he instructed his crew to be ready for battle. Light winds kept Juno in the area until 10 August 1805. As he tried to maneuver Juno out into the strait the ship was caught in an ebbing tide and struck a rock. Juno was stranded until high tide. DeWolf readied the ships for a possible attack and the possibility of keeling over. By chance, the keel of Juno was balanced on three rocks which kept it from capsizing. During low tide the crew was able to examine the ship's bottom and do a few repairs. In the morning many Tlingit came in canoes. While some trading was done DeWolf tried to prevent the possibility of attack by taking a Tlingit hostage. It turned out that Juno was not badly damaged and was seaworthy with in the incoming tide. DeWolf released his hostage with "a very liberal present for his detention", and made for Sitka. His examination of the ship's bottom showed the poor state of the copper cladding. DeWolf hoped to make better repairs at Sitka.[8]

Wintering at Sitka 1805-1806

On the way DeWolf encountered the Mary again and the two ships sailed together to Sitka, arriving on 14 August 1805. DeWolf wrote that Baranov welcomed him to Sitka "with that kind of obliging hospitality which made him loved and respected by every visitor". By this time DeWolf had collected about 1,000 sea otter furs. He arranged to have the Mary take them to sell in Guangzhou (Canton), the only port in China open to Western trade at the time. [8]

The Juno was brought ashore and repaired until 6 September 1805. Many floor timbers were repaired and the copper along the hull bottom was replaced. Despite the work, DeWolf wrote of Juno as "crippled", and that he would just have to carry on, "and endeavor to prosecute the remainder of our voyage with more caution".[8]

DeWolf proposed to Baranov a joint venture to hunt sea otters on the coast of Spanish California, despite such activity being considered illegal poaching by the Spanish. The plan involved about 50-60 RAC Aleut and Alutiiq hunters and their kayaks being taken aboard Juno, which would sail to California in October 1805. This kind of joint venture was first done in 1803–1804 by the American trader Joseph O'Cain. Baranov agreed to DeWolf's proposal.[8] However, on 26 August 1805 the Russian ship Maria arrived at Sitka. The Maria, under Andrei Vasilevish Mashin, brought several passengers whose presence changed the course of events for DeWolf. These included the nobleman Nikolai Rezanov, Russia's ambassador to Japan, plenipotentiary of Tsar Alexander I of Russia, and part owner of the Russian–American Company, and Georg von Langsdorff, a German naturalist and physician working as a diplomat representing the Russian Empire, and officers of the Russian Imperial Navy including Gavriil Ivanovich Davydov and Nikolai Aleksandrovich Khvostov. The Maria also brought carpenters and supplies for building two new RAC vessels at Sitka.[8]

With the Russian post at Sitka less than a year old and still under construction, and with supplies dwindling, Baranov was not able to comfortably shelter the Russians newly arrived on Maria and the crew of Juno. DeWolf wrote that there were 150 Russians and 250 Alutiiq and Aleut hunters, plus his own crew, at Sitka. Everyone was actively preparing for the coming winter, building workshops, barracks, and other structures. The planned construction of a new RAC ship was postponed. DeWolf, learning how difficult and expensive the new ship's construction would be "jocosely", as he described it, told Langsdorff and Rezanov that he would sell Juno to the RAC. Rezanov immediately agreed. Acutely aware of the RAC's shortage of ships, Rezanov was willing to pay far more than Juno would have gone for elsewhere.[14] DeWolf, surprised by Rezanov's earnestness, began talks about actually selling his ship. After some deliberations, it was agreed that the Juno would be sold to the RAC for $68,000 (worth approximately $1,500,000 in 2023), which would be paid with bills of exchange on the Directors of the RAC in Saint Petersburg worth $54,638, 572 sea otter furs worth $13,062, a small and poorly-built Russian vessel called Ermak (also transliterated as Yermak) with which DeWolf's crew could take the furs to China, and $300 in cash.[8][11] The RAC, desperate for sailing vessels, paid about twice what Juno and her entire cargo had cost the DeWolf family.[10][3]

On 5 October 1805 the Ermak was transferred to DeWolf and Juno to the RAC. The US flag was taken from Juno and raised on Ermak. The Juno was renamed Yunona. On 27 October 1805 Ermak left for China via Hawaii, under the command of George Stetson, one of DeWolf's officers. DeWolf himself agreed to stay at Sitka until the spring of 1806, after which he would travel with Rezanov across Siberia to St. Petersburg.[8][11]

Over the winter of 1805–06, DeWolf and Langsdorff became close friends. They went on hunts for game and to collect specimens for Langsdorff's interests in natural history. They learned how to use and navigate in native baidarkas (Aleutian kayaks). In November, while Rezanov was away with Juno acquiring supplies from Kodiak Island, DeWolf and Langsdorff decided to visit the Tlingit who had been displaced from the Sitka area after the 1804 Battle of Sitka. Baranov reluctantly agreed to provide them with several Alutiiq men and the daughter of a Tlingit clan head to serve as translator. It took them three days to reach the Tlingit fortified settlement where they stayed for two days. They got back to Sitka about the same time that Rezanov returned in Juno.[8]

The Tlingit stronghold was known as Tchartle nu ou or Chartle con nu, meaning "Halibut Fort" or "Fort on the Halibut". Its exact location is not certain, variously described as being at Point Hayes or Point Craven,[15][16] perhaps on one of the small islands nearby in the eastern end of Peril Strait; or at Lindenberg Head in Peril Strait,[17] about 6 mi (9.7 km) west of Point Craven. Langsdorff described the house of Chief Dlchaetin as having a raised hearth in the middle of an interior open space large enough to hold the several hundred Tlingit who gathered to see Langsdorff and DeWolf.[18]

DeWolf noted that both Tlingit men and women "are expert in the use of fire-arms, and are excellent judges of their quality." Langsdorff wrote that Tlingit weapons "consist principally of bows and arrows; but since their trade with the American States, they have acquired so large a stock of guns, powder, and shot, that they scarcely use their arrows except in hunting sea otters and [seals]." And that the Tlingit "understand the qualities of a good gun so well that it is impossible to impose a bad one upon them: even the women are accustomed to the use of fire-arms, and often go out on the hunting parties". He also wrote that DeWolf "assured me that the best English guns may now be bought cheaper upon the north-west coast of American than in England".[18]

Over the winter DeWolf, Langsdorff, Rezanov, other special guests, and officers of the RAC and Russian Navy lived decently, enjoying the provisions DeWolf had brought aboard Juno, while the common workers at Sitka suffered from overwork, malnutrition, and scurvy. DeWolf made special note of the strong social disparities at Sitka in his memoirs. While he was there, the food shortage became an emergency and scurvy began impacting work at Sitka, such as the construction of a new ship, dubbed Avos. So Rezanov and Langsdorff took Juno, captained by Nikolai Khvostov, to Spanish California to acquire provisions. They left on 8 March 1806 and returned on 21 June. On the way they tried but failed to enter the Columbia River, hoping to reconnoiter for a possible Russian outpost near the river's mouth. Thus they came very close to meeting Lewis and Clark. The Russians continued to San Francisco, where they were welcomed by Governor José Joaquín de Arrillaga and allowed to acquire provisions for Sitka. Rezanov tried to establish regular trade between California and Russian Alaska, but both governments give little heed.[12][19][20]

In May, while Juno was away, the American ship O'Cain, under Jonathan Winship, arrived from Boston via Hawaii. Winship, hoping to repeat the earlier joint venture done with O'Cain under Captain Joseph O'Cain, proposed a joint venture with Baranov to hunt California sea otters with Alutiiq and Aleut hunters brought to California on the O'Cain. This was agreed to and arranged, with O'Cain leaving in mid-May with over 120 Alutiiq and Aleut hunters and 75 baidarkas.[21][8]

By late June, when Rezanov and Langsdorff returned with Juno, DeWolf was becoming increasingly bored and worried about being able to get to Siberia before unfavorable weather would prevent his departure for another season. Rezanov did not want to send Juno west until Avos was finished. The only other available vessel was the Rostislav (also transliterated Russisloff), a small brig of about 25 tons burden.[10] DeWolf asked if he could captain Rostislav to Siberia himself. Langsdorff, who had also grown tired of Russian America, was excited by the idea. Baranov and Rezanov agreed, and on 30 June 1806 the Rostislav was made ready to sail with a crew of ten men. Shortly after, DeWolf and Langsdorff left Sitka. The Rostislav proved seaworthy but very slow, especially in the light summer winds. They reached Kodiak on 13 July, and Unalaska on 12 August. They then sailed for the Kuril Islands, hoping to reach Okhotsk, the starting point of the overland route across Siberia. DeWolf neared the Sea of Okhotsk in early September, but bad weather prevented Rostislav from entering the sea. DeWolf was forced to instead sail to Petropavlovsk on the coast of the Kamchatka Peninsula, where he would have to spent the winter of 1806–07. The Rostislav arrived at Petropavlovsk on 22 September 1806.[8]

Wintering at Petropavlovsk 1806-1807

Not long after DeWolf arrived at Petropavlovsk two Russian ships arrived bringing people DeWolf had met in Sitka. First, Avos arrived, under command of Davydov. Then DeWolf's old ship Juno, under Khvostov. The two vessels, with Rezanov on Juno, had just conducted a raid on Japanese settlements on Sakhalin Island. Rezanov had been dropped off at Okhotsk. Several Japanese prisoners were brought to Petropavlovsk. The Russians planned to bring the Japanese prisoners to Japan in early 1807 in hopes of breaking through Japan's isolationist sakoku policy and establishing trade relations.[8]

Over the winter DeWolf learned to use dog sleds, which were the main form of winter transportation in Kamchatka. He and Langsdorff made a number of dog sled expeditions, sometimes together, sometimes with Davydov and Khvostov. DeWolf visited villages in the vicinity of Petropavlovsk and, as his confidence increased, took longer trips around the southern end of the Kamchatka Peninsula.[8][12]

Khvostov and Davydov left for the Kuril Islands in March. Due to ice in the Sea of Okhotsk, DeWolf and Langsdroff had to wait until 26 May 1807 to depart Petropavlovsk for Okhotsk with Rostislav. On 30 May they ran into a large whale. DeWolf later wrote that the impact was "like striking a rock" and that the Rostislav, upon the whale's back, was raised 2–3 feet out of the water. Langsdorff recalled the incident in a similar way—that they had run into a whale, which "could have been disastrous if the boat listed or was shaken too hard by the impact, but Captain DeWolf acted quite competently".[8] In later years DeWolf recounted this story to his nephew Herman Melville, who included it in Moby Dick, Chapter 45, quoting Langsdorff account of the whale.[1]

Overland across Siberia

On 27 June 1807 DeWolf anchored Rostislav at Okhotsk. There he and Langsdorff leaarned that Rezanov had fallen ill and died on 13 March 1807. DeWolf made preparations for the start of his overland trip across Russia to Saint Petersburg. Langsdorff had other plans, so DeWolf traveled without him. He left for Yakutsk on 3 July 1807, with eleven horses and a Yakuts guide. He took the main route, which proved to be rough and difficult. He arrived at Yakutsk on 26 July 1807.[8]

From Yakutsk DeWolf traveled to Irkutsk by boat on the Lena River. A Cossack traveled with him on the boat, and DeWolf noted how the provincial population treated the Cossack and himself with great deference. He later wrote that as an "American captain" traveling to Saint Petersburg "on government business", the local peoples held him in very high regard. At one point the boat stopped near a village that was experiencing an outbreak of smallpox. DeWolf helped inoculate villagers using a technique he learned in the USA. He ran a thread through the lesions of infected villagers, then cut the thread into small pieces, which were put into small incisions made in the arms of uninfected villagers. This technique usually made people immune to smallpox.[8]

DeWolf arrived at Irkutsk on 28 August 1807. There he met up with an RAC official who provided room and board. He also ran into his friend Langsdorff, who was on his way to Kyakhta, the only place where China allowed Russia to trade, via a crossing of Lake Baikal. So the friends soon parted ways again. The rest of DeWolf's trip across Russia was relatively uneventful. He reached Tomsk on 10 September 1807, then Kazan on 30 September, then Moscow on 8 October. He stayed in Moscow until 17 October before leaving for Saint Petersburg, which he reached on 21 October 1807.[8]

At Saint Petersburg DeWolf went to the RAC headquarters where he was introduced to the RAC Director, Mikhail Matveevich Buldakov, who, like Rezanov, was a son-in-law of the influential pre-RAC Alaskan fur trader Grigory Shelikhov. Language difficulties were resolved by the appearance of the American Benedict Cramer, a partner in the banking firm Cramer, Smith and Company, and a member of the RAC Board of Directors. Cramer was already familiar with DeWolf's sale of Juno and helped facilitate the payments owed. The bills of exchange DeWolf had been given in Sitka were honored in Spanish dollars. The proceeds were then invested in hemp, iron, and manufactured goods, and sent to the USA.[8]

After payment, DeWolf was free to enjoy himself in Saint Petersburg, where Director Buldakov put him up. During his stay, DeWolf met Levitt Harris, the American Consul General in Russia, as well as Count Nikolay Rumyantsev, the Minister of Commerce and future Minister of Foreign Affairs. Rumyantsev was also the principal financier of the expedition that had taken Rezanov and Langdorff to Russian America. DeWolf planned to stay in Saint Petersburg until late November, but the outbreak of the Anglo-Russian War between Russia and the United Kingdom hastened his departure. He found transport on a small Dutch ship and left Saint Petersburg in early November, arriving at Helsingør (Elsinore), near Copenhagen, Denmark, on 13 November 1807.[8]

In Denmark, DeWolf met Captain David Gray, an American merchant from Portland, Maine. Gray agreed to take DeWolf to America. They quickly reached Liverpool, England, but had to spend the winter of 1807–1808 there while Gray's ship underwent repairs. They left Liverpool on 7 February 1808 and arrived in Portland, Maine, on 25 March.[8] From Portland, DeWolf traveled by stagecoach to Bristol, Rhode Island, arriving home on 1 April 1808.[3] From departure to return, DeWolf's trip had taken almost four years. Overall, the expedition netted the DeWolf family over $100,000, a considerable profit at the time.[8] John DeWolf's epic voyage earned him the nickname Nor'west John.[3]

John DeWolf's expedition had a large impact on his life. He had made valuable contacts in Russia which led to trade relationships. He adventures made him a local celebrity, and he told his stories to many people over the years until he finally wrote a book about it, titled A Voyage to the North Pacific and a Journey Through Siberia: More Than Half a Century Ago, published in 1861.[12]

Later life

After his circumnavigation, DeWolf participated in many other voyages as a businessman, making various international business contracts over a long and successful career.[7] Making good on his Russian connections, he managed the DeWolf family's trade with Russia via the Baltic Sea. This DeWolf–Russian trade lasted into the 1820s.[8]

By 1823 DeWolf established one of the four American mercantile houses that were operating in Honolulu at that time.[22] These trading houses were stocked with goods that were in demand by Native Hawaiians and the growing number of Americans and other foreigners who lived in Hawaii. Profits were made by selling goods mostly in exchange for Hawaiian sandalwood (ʻiliahi or ʻiliahialoʻe), which was a booming business in the 1820s. As whaling ships began visiting Hawaii in larger numbers the mercantile community grew and whaling bills of exchange became increasingly common. By 1830 Hawaii had become a major commercial center for the entire North Pacific, with connections to California, China, Russia, and many Pacific Islands. The main ports of call were Honolulu on Oahu and Lahaina on Maui. American goods were largely brought from New England, and buildings commonly used a distinctly New England style similar to the "Yankee" architecture of the whaling centers of New Bedford and Nantucket.[23]

In 1829 DeWolf gave up sea voyages and settled down in Bristol.[3] He lived on Hope Street, in what became known as the "Capt. John DeWolf House". He managed what is now known as "Capt. John DeWolf's Store", at 54 State Street. Both buildings were in what is now the Bristol Waterfront Historic District.[6] The National Register of Historic Places describes "Capt. John DeWolf's Store" as "owned by the famous "Nor'west John" DeWolf, first American to cross Siberia after selling his ship in Alaska to a fur trade official of the Russian-American Company".[6]

In 1814 DeWolf married Mary Melville, aunt of Herman Melville. They had two children: Nancy Melville DeWolf (1814-1901) and John Langsdorff DeWolf (1817-1886).[7] In 1850, he and Mary moved in with their married daughter, Nancy Downer, in Dorchester, Massachusetts.[3]

DeWolf is known for inspiring his nephew Herman Melville, including a dramatic account of an encounter with a huge whale that lifted his ship out of the water—a story which contributed to Melville's conception of Moby Dick. DeWolf is mentioned in Moby Dick.[7] Herman Melville spent the summer of 1828 living with the DeWolfs in Bristol, during which time "Nor'west John" told him many stories about his adventures, which contributed to Herman's later inspiration to write Moby Dick. In Moby Dick Melville included explicit mentions of DeWolf and George Heinrich von Langsdorff, who DeWolf met and befriended in Russian Alaska.[8]

DeWolf died in Dorchester, Massachusetts, at the home of his daughter, on 8 March 1872. He was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame in 1967.[7] He is buried in Forest Hills Cemetery, Jamaica Plain, Boston.

See also

References

- 1 2 Melville, Herman (1851). "Chapter XLV: The Affidavit". Moby Dick; or, The Whale. Retrieved 24 July 2023 – via Power Moby-Dick: The Online Annotation.

- ↑ DeWolf, Thomas Norman (2008). Inheriting the Trade: A Northern Family Confronts Its Legacy as the Largest Slave-trading Dynasty in U.S. History. Beacon Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780807072813. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nadalin, Christy (11 January 2018). "New year marks anniversary of local explorer's epic voyage". EastBayRI. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ↑ "John DeWolf". Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ↑ Conley, Patrick T. (2023). The Makers of Modern Rhode Island. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781467154024. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 "NRHP nomination for Bristol Waterfront Historic District". National Park Service. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "John D'Wolf letters, Department of Special Collections". Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Shorey, Tobin Jerel (2014). Navigating the 'Drunken Republic': The Juno and the Russian American Frontier, 1799-1811 (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Florida. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- 1 2 Shorey, Tobin (30 May 2015). "A Brief History of the Vessel JUNO, 1799-1811". Alaska Historical Society. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 "D'Wolf, John". ABC BookWorld. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 "A Brief History of the Vessel JUNO, 1799-1811". Alaska Historical Society. 30 May 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 D'Wolf, John (1861). A Voyage to the North Pacific and a Journey Through Siberia: More Than Half a Century Ago. Cambridge, MA: Welch, Bigelow. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ↑ "Heiltsuk Adjucation Report; Dáduqvḷá qṇtxv Ǧviḷásax: To look at our traditional laws" (PDF). Heiltsuk Tribal Council. May 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ Stephens, Oren M. (1961). "When the Russian Bear Embraced America's Coast". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 11 (2): 44–54. JSTOR 4516479. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Point Hayes

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Point Craven

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Lindenberg Head

- 1 2 Emmons, George Thornton; De Laguna, Frederica (1991). The Tlingit Indians. University of Washington Press. pp. 76–77, 132. ISBN 9780295970080. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ↑ Owens, Kenneth N. (2016). Empire Maker: Aleksandr Baranov and Russian Colonial Expansion into Alaska and Northern California. University of Washington Press. pp. 214–216. ISBN 978-0-295-80583-2. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ↑ Rezanov, Nikolai Petrovich; Pierce, Richard Austin; Khvostov, Nikolai Aleksandrovich; Langsdorff, G.H. von (1972). Pierce, Richard Austin (ed.). Rezanov Reconnoiters California, 1806: A new translation of Rezanov's letter, parts of Lieutenant Khvostov's log of the ship Juno, and Dr. Georg von Langsdorff observations (PDF). San Francisco: The Book Club of California. OCLC 571672. Retrieved 23 July 2023 – via Fort Ross Conservancy Library.

- ↑ Malloy, Mary (1998). "Boston Men" on the Northwest Coast: The American Maritime Fur Trade 1788-1844. The Limestone Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-895901-18-4.

- ↑ Morison, S.E. (1921). "Boston Traders in Hawaiian Islands, 1789–1823". The Washington Historical Quarterly. 12 (3): 177. JSTOR 40473740. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ↑ Kuykendall, Ralph S. (1934). "Early Hawaiian Commercial Development". Pacific Historical Review. 3 (4): 365–385. doi:10.2307/3633142. JSTOR 3633142. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

External links

- Polishchuk, Igor. "September 2021 Enews: Encounter With a Whale". Fort Ross Conservancy.

Further reading

- Coleman, Peter J. (Winter 1963). "The Entrepreneurial Spirit in Rhode Island History". The Business History Review. 37 (4): 319–344. doi:10.2307/3112713. JSTOR 3112713. S2CID 155253916.

- Dauenhauer, Nora; Dauenhauer, Richard; Black, Lydia (2008). Anóoshi lingit aaní ká / Russians in Tlingit America : the battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295986012.

- Grinëv, Andreĭ Valʹterovich (2005). The Tlingit Indians in Russian America, 1741-1867. Translated by Bland, Richard L.; Solovjova, Katerina G. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803220713.

- Gunther, Erna (2022). Indian Life on the Northwest Coast of North America as seen by the Early Explorers and Fur Traders during the Last Decades of the Eighteenth Century. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226310879.

- Johnson, Cynthia Mestad (2014). James DeWolf and the Rhode Island Slave Trade. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781625850157.

- Howe, George (April 1959). "The Voyage of Nor'west John". American Heritgage.

- Langsdorff, G. H. von. Voyages and Travels in Various Parts of the World, during the Years 1803, 1804, 1805, 1806, and 1807. Illustrated by Engravings from Original Drawings. London: Printed for Henry Colburn and Sold by George Goldie, Edinburgh; and John Cumming, Dublin, 1813. (hdl:2027/nyp.33433000405047)

- "Review of Voyages and Travels in Various Parts of the World, during the Years 1803, 1804, 1805, 1806, and 1807 by G. H. Von Langsdorff". The Quarterly Review. 9: 433–443. July 1813. hdl:2027/hvd.32044092624576.

- Malloy, Mary (2006). Devil on the Deep Blue Sea: The Notorious Career of Captain Samuel Hill of Boston. Bullbrier Press. ISBN 9780972285414.

- Matthews, Owen (2015). Glorious Misadventures: Nikolai Rezanov and the Dream of a Russian America. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781408833995.

- Owens, Kenneth (Autumn 2006). "Frontiersman for the Tsar: Timofei Tarakanov and the Expansion of Russian America". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. Montana Historical Society. 56 (3): 3–21, 93–94. JSTOR 4520817.

- Perry, Calbraith Bourn (1902). Ancestors and Decendants: Being a Complete Genealogy of the Rhode Island D'Wolf's, the Descendants of Simon De Wold, with Their Common Descent from Balthasar De Wolf, of Lyme, Conn. (1668), with a Bibliographical Introduction and Appendices on the Nova Scotian de Wolfs and Other Allied Families. Press of T.A. Wright.

- Phelps, Wiliam Dane; Sturgis, William; Swan, James Gilchrist (1997). Busch, Briton Cooper; Gough, Barry M. (eds.). Fur Traders from New England: The Boston Men in the North Pacific, 1787-1800. Spokane: Arthur H. Clark Company.