Joseph Grinnell | |

|---|---|

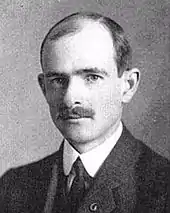

Joseph Grinnell in 1901 | |

| Born | February 27, 1877 Indian Territory near Fort Sill, Oklahoma |

| Died | May 29, 1939 (aged 62) |

| Education | Pasadena HS, Throop Polytechnic, Stanford |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for |

|

| Spouse | Hilda Wood Grinnell |

| Children | Willard, Stuart, Richard and Mary Elizabeth |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Zoology |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | An account of the mammals and birds of the lower Colorado Valley, with especial reference to the distributional problems presented (1913) |

| Doctoral advisor | Charles Henry Gilbert |

| Doctoral students | Ian McTaggart-Cowan, E. Raymond Hall, Robert T. Orr |

| Signature | |

Joseph Grinnell (February 27, 1877 – May 29, 1939) was an American field biologist and zoologist. He made extensive studies of the fauna of California, and is credited with introducing a method of recording precise field observations known as the Grinnell System.[1] He served as the first director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California, Berkeley from the museum's inception in 1908 until his death.[2]

He edited The Condor, a publication of the Cooper Ornithological Club, from 1906 to 1939, and authored many articles for scientific journals and ornithological magazines. He wrote several books, among them The Distribution of the Birds of California and Animal Life in the Yosemite.[3] He also developed and popularized the concept of the niche.[4]

Early years

Joseph Grinnell was born February 27, 1877, the first of three children by his father Fordyce Grinnell MD and mother Sarah Elizabeth Pratt. Grinnell's father worked as the physician for the Kiowa, Comanche and Wichita Indian Agency near Fort Sill, Oklahoma. His distant cousins included the Massachusetts politician Joseph Grinnell (1788–1885) and George Bird Grinnell (1849–1938) who founded the Audubon Society. The Grinnells moved to the Pine Ridge Indian Agency in 1880.[5]

In 1885 the Grinnell family moved to Pasadena, California, but the collapse of Southern California's boom forced Dr. Grinnell in 1888 to accept a position at the Indian school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The Carlisle Indian school commander was Captain Richard Henry Pratt, a friend of the Grinnells. Joseph Grinnell worked in a printing shop in Carlisle and collected his first specimen, a toad, before the family returned to Pasadena two years later.[5]

First Alaska trip

Captain Pratt visited the Grinnells in Pasadena in 1896 while on a new assignment to inspect Indian Schools on the Pacific coast up to Alaska. The captain obtained permission from the family to take young Grinnell with him. Grinnell sent home bird specimens of the San Francisco Bay area, en route to Alaska. Captain Pratt completed his assignment and returned home. Grinnell remained in Alaska and continued collecting with the assistance of the Sheldon Jackson Museum in Haines, Alaska.[5]

Grinnell went on field trips throughout the area, including remote Saint Lazaria Island. An unintended overnight stay on the island enabled him to study storm-petrels, an account of which he published in the March 1897 issue of the Nidologist,[5] an early publication of the Cooper Ornithological Club.[6]

Grinnell's expanding collection attracted visitors who were tourists, summer residents and visiting naturalists, including John Muir, Henry Fairfield Osborn, and ornithologist Joseph Mailliard. Grinnell returned to Pasadena in the fall of 1897 where he continued field work in the nearby mountains and canyons. [5]

Second Alaska trip

published in 1901

Grinnell's second visit to the far north began in 1898 on the schooner Penelope. He spent 18 months in Alaska during the Klondike Gold Rush. Grinnell corresponded regularly with his family, the letters were later compiled and edited into the book Gold Hunting in Alaska, published by David C. Cook Publishing Company in 1901.[5] Grinnell joined the Long Beach and Alaska Mining and Trading Company to Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. The company landed at Cape Blossom in Kotzebue Sound in July 1898. Grinnell collected and observed the summer migrant bird life; Gambel's sparrow, barn swallow, and Savannah sparrow, among others. By August, Grinnell had 75 bird specimens preserved, including a Siberian yellow wagtail. The miners spent the winter inland on the Kowak River [Kobuk River], then returned to the coast that spring.[7]

The company sailed on the Penelope to Cape Nome in July 1899. At Cape Nome, Grinnell's job was amalgamating the gold using mercury. The gold stampede to the Nome area in the period 1899–1900 was Alaska's largest in both amount of gold recovered and population increase. The gold fields yielded more than $57 million from 1898 to 1910. The site is now a National Historic Landmark, the Cape Nome Mining District Discovery Sites.[8] In Grinnell's letters, he described a chaotic scene as "the entire eight miles there is scarcely one hundred feet without one or more tents on it ... our claims are now covered with beach jumpers and we cannot get them off. Mob law rules."[7]

The Cooper Ornithological Club published Grinnell's field notes in 1900 as Pacific Coast Avifauna, no. 1.[5]

Education

Grinnell was graduated from Pasadena High School in 1893 and enrolled in Throop Polytechnic Institute (now California Institute of Technology) that autumn, where he received his bachelor's degree in 1897.[9]

In 1901 Grinnell received his master's degree from Stanford University.[3] At Stanford, he met several influential people, among them were Edmund Heller. Heller would later join an expedition to Peru in 1915 to explore newly discovered ruins of an Incan civilization at Machu Picchu.[10]

During his time at Stanford Grinnell formed the plan for a list of birds of California. He worked on that project for the next 38 years. He was finishing the third installment to Bibliography of California Ornithology when he died in 1939.[5]

Grinnell supported himself at Stanford by teaching at Palo Alto High School and working in Stanford's Hopkins Seaside Laboratory. At Hopkins, Grinnell taught embryology in the summer of 1900 and in the summers of 1901 and 1902, ornithology.[5]

A case of typhoid fever interrupted Grinnell's academic track and he returned to Pasadena in 1903 to recover. Grinnell accepted an offer as biology instructor at Throop Polytechnic during this time. Grinnell finished his Stanford Doctorate requirements—essentially by mail—with submission of his thesis An Account of the Mammals and Birds of the Lower Colorado Valley with Especial Reference to the Distributional Problems Presented and received his Doctorate in Zoology on May 19, 1913.[5][11]

Students of Grinnell's biology class at Throop included Charles Lewis Camp and Joseph S. Dixon. Charles Camp would become the director of the University of California Museum of Paleontology. Joseph Dixon would join John Thayer's sponsored expedition in 1913 to Alaska. The Thayer expedition almost perished when their ship became locked in ice 7 nautical miles (13 km) off the coast, east of Point Barrow until the summer of 1914. Dixon collected specimens during this time, including a new species of gull, Larus thayeri which was named for the expedition's sponsor.[12]

Hilda Wood Grinnell

Grinnell married Hilda Wood on June 22, 1906. Wood was born in Tombstone, Arizona May 29, 1883. She was one of Grinnell's students at Throop and later his teaching assistant in zoology. Wood received her bachelor's degree from Throop in 1906. The Grinnells moved to Berkeley in 1908 and in 1913, Hilda earned her master's degree at the University of California, Berkeley. She wrote articles for publications in The Condor and the Journal of Mammalogy and was a member of the American Ornithologists' Union and the California Academy of Sciences. Hilda Grinnell authored a 32-page biography in the January–February 1940 issue of The Condor.[5]

Hilda continued Grinnell's work on The Distribution of the Birds of California; maintained Grinnell's system of bibliographic entries, consulted the catalogs for accuracy, and read proofs and copy with the book's junior author, Alden H. Miller.[13]

Museum of Vertebrate Zoology

Annie Montague Alexander, philanthropist, naturalist and explorer, founded the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California (UC) in 1908. Alexander named Grinnell as museum director the same year. She believed that Grinnell was the right choice as director to the point that she was prepared to withdraw the endowment if UC officials objected to Grinnell.[14]

Historic meeting

Alexander met Grinnell in January 1907 while preparing for her expedition to Alaska; she came to Throop's biology department to find Joseph Dixon, Grinnell's student. Dixon had been recommended to Alexander by Frank Stephens, author of California Mammals. Grinnell endorsed Dixon as a member of Alexander's expedition, as they discussed Alaska. Grinnell invited Alexander to his home to view his collections, which she did before returning to Oakland. The name Annie M. Alexander seemed familiar and Grinnell found reprints among his papers from paleontologist John C. Merriam to Alexander, thanking her for her work and financial support. Satisfied of her commitment to research, he sent her a letter outlining specific points on field work that would maximize scientific results from the seven-member expedition.[15]

Alexander returned to California in the summer of 1907. She invited Grinnell to view the Alaska specimens. During the Thanksgiving holiday he met with Alexander at her home. The pair exchanged ideas for a museum on the West Coast that would be on par with the institutions of the eastern United States, such as the Smithsonian Institution. Alexander and Grinnell believed the fauna and flora of the western territory was fast disappearing as a result of human impact, thus detailed documentation was essential for both posterity and knowledge. This foresight proved useful almost a century later, when researchers at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology would use the Grinnell field notes to compare changes in California fauna.[16]

Grinnell and Alexander differed on where the museum should be located. Grinnell advocated for Stanford while Alexander, impressed by the University of California (UC) paleontology lectures she had attended, determined that the museum would be at UC.[17]

Alexander elaborated on the job requirements in a letter to Grinnell dated September, 1907 after she returned from Alaska: "I should like to see a collection developed (more especially of the California fauna) and would be glad to give what support I could if I could find the right man to take hold; someone interested not only in bringing a collection together but with the larger object in view, namely gathering data in connection with the work that would have direct bearing on the important biological issues of the day. Work systematically and intelligently carried on is the work that counts."[18]

Alexander appointed Grinnell director for one year, although he held that post for the remainder of his life. He named the museum and in 1909, donated his collection of mammals, also his bound files of The Auk, The Condor and other publications.[5] He gave his entire collection of bird specimens to the museum in 1920. The bird collection numbered more than 8,000.[3]

The relationship between museum director and benefactess was unusual. Grinnell deferred to Alexander's wishes in almost every aspect of the museum's business. Alexander, in turn, expected Grinnell to devote all his time and energy to the enterprise, to continue research and publishing, in addition to the duties of director.[19]

In 1908, Alexander had written to Grinnell asking for a recommendation of someone suitable for the upcoming 1908 expedition. His reply elicited a sharp response from Alexander: "Am rather relieved you could not recommend a lady for our trip, though regret your evident contempt of women as naturalists ... ." Alexander found Louise Kellogg to join the Alaska trip. A subsequent letter from Grinnell was even more frank, "I do hope your discovery [of a companion] proves tractable and industrious. One good test might be to have her string tags [specimen labels] for five hours straight!"[20]

Alexander supported the museum financially; during the ensuing 46 years, she contributed more than $1.5 million.[5][17]

Editor of The Condor

The Condor is one of three publications by the Cooper Ornithological Club (or Society), one of the largest non-profit ornithological organizations in the world, named for James G. Cooper, a California naturalist.[21]

The magazine's first editor was Chester Barlow, a charter member of the club and editor until his death in 1902 at age 28 of tuberculosis.[22][23] Joseph Grinnell was listed as editor beginning with the January 1906 issue, replacing Walter K. Fisher. The main office of the magazine moved to Pasadena from Santa Clara, California, when Grinnell, who still lived in Pasadena, became editor.[23]

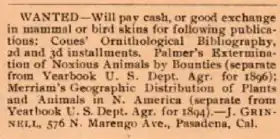

The Condor published classified ads which listed items to buy, sell or trade for other specimens, collections, guns, cameras or publications. Species and their eggs for sale or exchange included rare birds like the California condor and bald eagle.[24]

Grinnell also advertised to trade specimens in the magazine; the November 1906 issue contained the ad: "Wanted – will pay cash or good exchange in mammal or bird skins".[24] In the same 1906 issue, Grinnell commented on Thomas Harrison Montgomery's article questioning the scientific benefit of egg collection (Oology) in Audubon Society's Bird-Lore publication. Grinnell defends the collecting and study of birds' eggs in his editorial "Is Egg-collecting Justifiable?" and includes recreation as one of the values gained. "Then there is the recreative phase which is not to be disparaged; and the pleasure to be derived from this pursuit. We must confess that we have gotten more complete satisfaction, in other words happiness [italics in original], out of one vacation trip into the mountains after rare birds and eggs than out of our two years of University work in embryology!"[25]

Grinnell edited The Condor for 33 years. He was one of the most influential, serving during the magazine's early years of development. As editor, he was democratic in some ways, asking members to vote on possible changes, like using metric units of measurement (the majority vote was no). He implemented "simplified spelling" which used phonetics, and can be seen in early-edition phrases. The magazine under Grinnell's tenure expanded from 175 to 223 current-format pages, and as of 1993, at 1,100 pages per year, is the largest of any major ornithological journal.[23]

Grinnell Method of note taking

Even though Joseph Grinnell found writing difficult, he put forth great effort to produce factual, precise writing. Author William Leon Dawson, wrote of Grinnell, "that some of his biographical sketches evince a keenness of insight, and bring out a wealth of first-hand information which mark him as potentially the foremost biographer of Western birds."[26]

Grinnell developed and implemented a detailed protocol for recording field observations. In conjunction with a catalog of captured specimens, a journal was kept, detailed accounts of individual species behaviors were recorded, topographic maps were annotated to show specific localities, and photographs were often taken of collecting sites and animals captured. These materials also documented weather conditions, vegetation types, vocalizations, and other evidence of animal presence in a given locale.[27]

The method has four components:

- A field notebook to directly record observations as they are happening.

- A field journal of fully written entries on observations and information, transcribed from the notes.

- A species account of the detailed observations on chosen species.

- A catalog is the record of where and when specimens were collected.

Grinnell's attention to detail included the type of paper for writing. "The India ink and paper of permanent quality will mean that our notes will be accessible 200 years from now." He added, "we are in the newest part of the new world where the population will be immense in fifty years at most."[28]

The Grinnell System (also Grinnell Method) is the procedure most often used by professional biologists and field naturalists.[1][29][30]

Survey of California fauna

Grinnell's goal for the museum was to build a collection primarily of California species, with comparative examples from outside the state. Representative sample areas of California were surveyed broadly, then in detail. The first field expedition for the new museum was to the Colorado Desert in April 1908. In 1910 three months were spent in the field along the Colorado River to study the river's effect as a barrier in the distribution of desert mammals. The Mount Whitney area, called the Whitney transect, was studied in 1911, the San Jacinto Mountains in 1913 and from 1914 to 1920, a cross-section of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, including Yosemite was surveyed. The Lassen Peak area was studied by Grinnell, Joseph S. Dixon and Jean M. Linsdale from 1924 to 1929.[5][31]

The field surveys also provided source material for Game Birds of California (1918) and Fur-bearing Mammals of California (1937).[5]

Yosemite

The 1914 Yosemite survey area consisted of 1,547 square miles (4,010 km2) in a narrow rectangle from eastern San Joaquin Valley, across the Sierra Nevada Range to the western edge of the Great Basin, including Mono Lake. There were 40 collecting stations, with one to five persons per station. The survey team collected animal specimens by shooting and setting out traps. Observations were recorded for animal behavior including their "workings", meaning nests or burrows. The survey team of eight researchers, including Grinnell and Joseph Dixon, produced 2,001 pages of field notes and 700 photographs . The research was published in 1924 as Animal Life in the Yosemite.[32]

Lassen Peak area

There were 50 sites surveyed throughout the Lassen region of northern California which documented the distributions of more than 350 species of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians, and collected more than 4,500 specimens. The results were published in the 1930 monograph Vertebrate Natural History of a Section of Northern California through the Lassen Peak Region. More than just a species checklist, this 600-page volume has behavioral observations and historic photographs. For many areas in the transect, the Lassen survey remains the most comprehensive vertebrate inventory yet conducted.[33]

The survey of California fauna was a test of Grinnell's theory that differences between species are driven by ecological and geographical barriers, a new idea in the science of biology of the 1940s. “He was looking at geographic variation and change of characters in space and time. He wanted to understand the kinds of factors that might influence local adaptation and … variation among individuals and within populations. These ideas were unique at the time because they called into question the accepted notion that species are static and unchanging.", noted Jim Patten, Professor Emeritus, in Berkeley Science Review.[34]

Grinnell Resurvey Project

The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology began the Grinnell Resurvey Project in 2002 using Grinnell's original survey of California fauna for comparison. The resurvey team encountered difficulties, as the 2007 report on Yosemite noted "the data from the original and current surveys cannot be directly compared because of differences in observer effort."[35]

Project researchers worked in Yosemite National Park from 2003 to 2006. Using colorfully annotated maps dating from the late 1800s, the biologists revisited about 40 sites. Some sites could not be resurveyed because they are no longer accessible; one example is Lake McClure, a reservoir constructed in 1926. Lassen National Park was resurveyed in 2006, and the Warner Mountains in northeast California and south to the White Mountains in 2007.

The resurvey report's section on birds noted problems in comparing the censuses: "In the original survey there was a large difference in terms of birds observed per unit time between J. Grinnell and T. Storer, with Grinnell having much higher scores than Storer for the same area. Grinnell and Storer counts also had a larger variation among their own censuses for a single site than we did during our survey."[35]

The Yosemite resurvey documented shifts in the geographic ranges of some mammals. The majority of change is to higher elevation by a ratio of 2.5 to 1.[35] A notable alteration in range is shown by the pinyon mouse (Peromyscus truei), where both the upper and lower range limits have moved upward in elevation. The resurvey biologists documented the pinyon mouse on Mount Lyell at elevation 10,500 feet.[35] In Grinnell's Animal Life of the Yosemite, the pinyon mouse (or big-eared white-footed mouse) is described as occurring in the Upper Sonoran Zone on the west slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

The Upper Sonoran is a life zone between 1,000 and 3,500 feet above sea level.[36]

Researchers have also observed selection-driven physical and genetic changes in populations of the Alpine chipmunk (Tamias alpinus), which was affected by contraction of its elevational range. While most parts of the chipmunk genome had not changed, there were shifts in variants of a gene related to regulation of the animals’ ability to survive in low-oxygen environments (ALOX15).[37][38]

In the Yosemite transect, no significant change in avian species abundance was found. Grinnell documented 133 species and the resurvey team reported 140 bird species.[35]

The report's section on amphibians and reptiles noted healthy populations of mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa) at Yosemite's Dorothy Lake and breeding populations near Evelyn Lake.[35] This species (or Distinct population segment) is listed as endangered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service.[39]

In 2013 a team of researchers from the San Diego Natural History Museum completed a five-year survey of the Grinnell Transect, Grinnell's 1908 study of the flora and fauna of Mount San Jacinto. In 60 surveys across 20 sites, they found the forest to be much denser than in Grinnell's time, with the loss of three species including a flying squirrel, and an increase in birds that like thick brush, such as the hermit thrush, the brown creeper and the Townsend's solitaire. The relative lack of leaf litter and decayed ground cover in Grinnell's time was considered to make the occurrence of hot and lasting fires in the forest impossible. With a much thicker understory in 2013, the team of researchers were forced by the Mountain Fire to evacuate their camp.[40]

Conservation

Grinnell worked on conservation issues in the latter part of his life. He wrote several articles: "Bird Life as a Community Asset" (1914), A Conservationist's Creed as to Wild-Life Administration" (1925), "Animal Life as an Asset of National Parks" (1916), and " Bats As Disirable Citizens" (1916). He tried to change National Park Service policies on predator control and on forest management. Additionally, he promoted the idea of a trained biologist or naturalist in national parks to conduct public education programs for visitors. He studied and published on the Point Lobos area on the California coast, and during the last two years of his life, studied animal life at Hastings Reserve in Santa Lucia Mountains of Carmel Valley, California.

National parks

The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology's Yosemite survey of 1914–1924 documented the area's wildlife. A second goal of the survey was education of the public as a means to protect the park. Yosemite was established in 1890. Total land area (excluding the valley, which was state-owned) was more than 1,500 square miles (3,900 km2). Congress reduced the park boundaries by one-third in 1905 in response to pressure from mining, grazing and logging interests. "Ultimately, Grinnell realized, whether in Yosemite, or across the nation, further assaults on wildlife habitat would only be blocked by a concerned and knowledgeable public." wrote historian Alfred Runte.[41]

Grinnell and Tracy I. Storer's article "Animal Life as an Asset to National Parks" was published in Science on September 15, 1916, and presented two major points. First, national parks could be examples of pristine nature and were valuable to science and the public. Second, parks could be outdoor classrooms for a trained naturalist to offer natural history classes, conduct walks, and provide other educational activities for park visitors.[42]

The newly created National Park Service, in the Department of Interior, had no public education programs in 1916, although director designate Stephen Mather had read Grinnell's article in Science. Grinnell was not the only advocate for education in the national parks. A letter from Interior Secretary Franklin Knight Lane to Director Mather in May 1918, constituted the Service's first administrative policy statement on the concept of the parks as educational media: "The educational, as well as the recreational, use of the national parks should be encouraged in every practicable way." Despite this high-level expression of support, the idea of the park service being in the education business – beyond dispensing basic tourist information – was not widely accepted.[43]

The first official natural history program at Yosemite began in 1920 with Harold C. Bryant and Loye Holmes Miller as park-employed naturalists.[44] Bryant viewed Grinnell as a mentor and went on to help design the interpretive program. He was awarded the Cornelius Armory Pugsley Medal in 1954 for his contributions to parks and conservation.[45]

Predator control

Grinnell argued in "Animal Life as an Asset to National Parks" against several park service management policies; one of which was the predator control program.[42] Congress had passed legislation a year earlier that instructed the Bureau of Biological Survey (now the US Fish and Wildlife Service) to destroy predators that "are injurious to agriculture and animal husbandry on the national forests and the public domain ...".[46] The new National Park Service agency used predator control agents from the bureau to trap wolves, coyotes, and mountain lions within park boundaries. The agency's first director, Stephen Mather saw his primary responsibility to the new national-park idea as one of building a constituency to support the parks, and feared that if predator populations were not controlled inside park boundaries, they would wander to adjoining private lands to kill livestock. Mather did not want angry ranchers complaining to their congressional representatives that the national parks were bad for the ranching business.[47]

Grinnell, George Melendez Wright, a student of Grinnell's, and others objected to the predator control policy. Grinnell argued that, "As a rule, predaceous animals should be left unmolested and allowed to retain their primitive relation to the rest of the fauna ... as their number is already kept within proper limits by the available food supply, nothing is to be gained by reducing it still further." But trapping of rare animals for scientific study was an exception, he added "A justifiable exception may be made when specimens are required for scientific purposes by authorized representatives of public institutions, and it should be remarked in this connection that without a scientific investigation of the animal life in the parks, and an extensive collection of specimens, no thorough understanding of the conditions or of the practical problems they involve is possible."[42]

In July 1915, during the Yosemite survey, Charles Lewis Camp trapped two wolverines, a male and female.[48] The survey results were published in Animal Life of the Yosemite with an entry on wolverine (Gulo gulo): "the wolverine is a rare animal anywhere in the Sierra Nevada. Its inclusion here is based upon the capture of two individuals at the head of Lyell Canyon."[49]

The last confirmed California wolverine was killed seven years later by local trapper and miner Albert J. Gardisky in Mono County near Saddlebag Lake on February 22, 1922. This complete specimen is located in the mammal collection at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology.[50][51] Since hunting and trapping had not yet been outlawed in national parks, Grinnell, the museum's director, initially took advantage of the situation, purchasing skins, skeletons and carcasses for the museum.[52]

Trapping was banned in Yosemite National Park by 1925, and in all national parks by 1931.[53]

Grinnell was aware of the possible extirpation of the wolverine in California by 1937, if not earlier, for he wrote a summary of all documentation, sightings, captures and stories on wolverines in Fur-bearing Mammals of California, with the last known sighting listed at 1924. Grinnell estimated " at the present time (1933) there are at most no more than 15 pairs of wolverine left in the State." He warned that there was a " necessity of a closed season for the wolverine if it was to escape the fate of the grizzly bear."[54]

Point Lobos State Reserve

A year-long study by Joseph Grinnell and the museum began in 1934 of the Point Lobos State Reserve in Monterey County for gathering "information which would show the kinds of land vertebrates present within the reserve, frequency of occurrence and relative abundance, habitat, relationship with the physical environment, and the annual cycle of its activity".[5] The research was published in 1935 as "Vertebrate Animals of Point Lobos Reserve".

Point Lobos nearly became a residential development before 1900. Preservationist Alexander McMillan Allen, the Save the Redwoods League environmental group and others began to buy back the residential lots in 1898. By 1933 it was added to the new state park system. In 1960, 750 acres (3.0 km2) undersea was added which created the first underwater reserve in the nation.[55] The reserve's name is from the offshore rocks at Punta de los Lobos Marinos, or Point of the Sea Wolves.[56]

Hastings Reserve

Russell P. Hastings offered the Hastings cattle ranch of 2,000 acres (8 km2) to the University of California for faunal studies, after learning about the research at Point Lobos. Grinnell began long-term faunal surveys on the Hastings ranch in upper Carmel Valley, Monterey County at the end of 1936 through 1939.[5]

The ranch became a field research station in 1937, and is the oldest and most productive unit in what is now the University's Natural Land and Water Reserves System, a system of 27 natural areas and biological field stations. Since its inception, Hastings has been managed by the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. The Hastings Reserve in one of only three fully protected reserves in the North Coast Ranges of California.[57]

Death

Grinnell's last field trip was in May 1938 to the Providence Mountains in San Bernardino County, Southern California. Grinnell's final specimen was a black-chinned sparrow. In the fall of that year, he took a leave of absence from the university during which he suffered a coronary. During his convalescence, a second coronary occurred. Grinnell died on May 29, 1939, in Berkeley, California, at age 62.[3][26]

The students and staff at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology formed the Grinnell Naturalists Society in 1940 to commemorate and continue the work of Joseph Grinnell. The Society was active from 1940 to 1952. The Bancroft Library maintains the organization's records and the collection is available for research purposes. The collection includes minutes of meetings, correspondence, newsletter file, questionnaire responses and account records.[58][59]

Selected published works

Joseph Grinnell authored or co-authored 554 published works, beginning in 1893 until 1939. A small sample is given below. A complete list by year is in the biography written by Hilda Wood Grinnell (see Cited literature section).

Joseph Grinnell co-authored several articles with his younger sister, Elizabeth J. Grinnell. Our Feathered Friends was published in 1898 and from 1900 to 1901, five articles were published in the regional magazine Land of Sunshine which was renamed Out West in 1901 and edited by Charles Fletcher Lummis.

Books

- Birds of the Kotzebue sound region, Alaska

- The game birds of California

- Animal Life in the Yosemite 1924

- Vertebrate Animals of Point Lobos Reserve 1936

- Fur-bearing Mammals of California 1937

Journal articles

- "The Catalina Island Quail" The Auk July 23, 1906

- "Wild Animal Life as a Product and as a Necessity of National Forests" The Journal of Forestry,

XXII, December 1924

- "Why We Need Wild Birds and Mammals" Scientific Monthly December 16, 1935

Other

- History of Pasadena by Hiram A. Reid 1895. Chapter titled "Our Native Birds".

- Travelers' Handbook to Southern California by George Wharton James, 1904. Chapter 20: "The Ornithologist in Southern California".

Honors

Two insects, four mammals, nine birds and one lizard were named after Joseph Grinnell. The Sitka kinglet (Regulus calendula grinnelli) was the first species named for Grinnell by ornithologist William Palmer in 1897. (Palmer was also a taxidermist and prepared the remains of the last passenger pigeon "Martha" when she died in 1914 at the Cincinnati, Ohio zoological gardens.)[60]

Joseph Grinnell was also the namesake of one of the Cal Falcons, "Grinnell", that bred at the Campanile from 2017-2022.[61]

The fish Synchiropus grinnelli, the Philippines dragonet, is a species of fish in the family Callionymidae, the dragonets. It is found in the Western Central Pacific from Philippines to Indonesia. It was named after him by Henry Weed Fowler.[62]

References

- 1 2 "United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station, General Technical Report PSW-GTR-144-Web-General Monitoring Procedures. Section: Journal Keeping". Fs.fed.us. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, "Joseph Grinnell (1877–1939) – MVZ's First Director"". Mvz.berkeley.edu. 1992-03-04. Archived from the original on 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- 1 2 3 4 The New York Times, "Joseph Grinnell, Noted Zoologist" May 30, 1939 (subscription to access archives required)

- ↑ Joseph Grinnell (1917). "The niche-relationships of the California Thrasher" (PDF). The Auk. 34 (4): 427–433. doi:10.2307/4072271. JSTOR 4072271. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2017-08-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Grinnell, Hilda Wood (January–February 1940). "Joseph Grinnell 1877–1939". The Condor. 42 (1): 3–34. doi:10.2307/1364313. JSTOR 1364313.

- ↑ A portion of Grinnell's article, "Petrels of Sitka, Alaska" reprinted in Life histories of North American petrels and pelicans and their allies; order Tubinares and order Steganopodes (1922) by Arthur C. Bent, United States National Museum, Smithsonian Bulletin 121, p. 136 The original article appeared in Nidologist (Cooper Ornithological Club) March vol.4 issue 7, 1897 (March issue is missing from Google's online copy of vols. 3–4.)

- 1 2 Grinnell, 1901

- ↑ National Park Service, National Historic Landmarks Program "Cape Nome Mining District Discovery Sites" Archived 2014-10-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hall, E. Raymond Joseph Grinnell 1877–1939 Allen Press 1939 p. 366

- ↑ "Smithsonian Institution "Record Unit 7179 Edmund Heller Papers,circa 1898–1918"". Siarchives.si.edu. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Grinnell, Joseph (1913). An account of the mammals and birds of the lower Colorado Valley, with especial reference to the distributional problems presented (Ph.D.). Stanford University. OCLC 2807652 – via ProQuest.

- ↑ Dixon, Joseph S. (1942). "Birds Observed between Pt Barrow and Herschel Island on the Arctic Coast of Alaska". The Condor. 45 (2): 49–57. doi:10.2307/1364377. JSTOR 1364377.

- ↑ Grinnell, Joseph and Alden H. Miller The Distribution of the Birds of California Cooper Ornithologists Club 1944 p. 8

- ↑ Stein, 2001, p. 79

- ↑ Stein, 2001, p. 65

- ↑ Stein, 2001, pp. 76–77

- 1 2 Williams, Rianna Annie Montague Alexander: Explorer, Naturalist, Philanthropist p. 6

- ↑ Stein, 2001, p. 75

- ↑ Stein, 2001, p. 94

- ↑ Stein, 2001 p. 100

- ↑ "Cooper Ornithological Society". Cooper.org. Archived from the original on 2013-04-10. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Taylor, Henry Reed (1903). "In Memoriam: Chester Barlow" (PDF). The Condor. 5 (1): 3–7. doi:10.2307/1361420. JSTOR 1361420.

- 1 2 3 Walsberg, Glenn E. (1993). "History of The Condor" (PDF). The Condor. 95 (3): 748–757. doi:10.2307/1369626. JSTOR 1369626.

- 1 2 "front matter" (PDF). The Condor. 8 (6). 1906. doi:10.2307/1361307. JSTOR 1361307.

- ↑ Grinnell, Joseph (1906). "Is Egg-collectiong Justifiable?" (PDF). The Condor. 8 (6): 155–156. doi:10.2307/1361317. JSTOR 1361317.

- 1 2 Linsdale, Jean (1942). "In Memoriam: Joseph Grinnell" (PDF). The Auk. 59 (2): 269–285. doi:10.2307/4079557. JSTOR 4079557.

- ↑ "UC Berkeley, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology "The Grinnell Method"". Mvz.berkeley.edu. 1992-03-04. Archived from the original on 2013-02-24. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Grinnell, Hilda Annie Montague Alexander Grinnell Naturalists Society, 1958, p. 8

- ↑ Herman, Steven G., The Naturalist's Field Journal – A Manual of Instruction Based on a System Established by Joseph Grinnell, Buteo Books, Vermillion, 1986, ISBN 0-931130-13-1

- ↑ Lehner, Philip Handbook of Ethological Methods Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 61, ISBN 0521637503

- ↑ "Museum of Vertebrate Zoology "Early Faunal Surveys by the MVZ"". Mvz.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-02-24. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Grinnell and Storer, 1924, pp. 1–3

- ↑ "Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, Grinnell Resurvey Project "Lassen Transect"". Mvz.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Spotswood, Erica "Getting Back To Nature: Revisiting the 1914 survey of California wildlife" Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine Berkeley Science Review No. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Moritz, Craig Final Report: A Re-survey of the Historic Grinnell-Storer Vertebrate Transect in Yosemite National Park, California Sierra Nevada Network Inventory and Monitoring Program – Sequoia, Kings Canyon National Parks June 2007.

- ↑ Grinnell and Storer, 1924, p. 111

- ↑ Card, Daren C.; Shapiro, Beth; Giribet, Gonzalo; Moritz, Craig; Edwards, Scott V. (23 November 2021). "Museum Genomics". Annual Review of Genetics. 55 (1): 633–659. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-071719-020506. ISSN 0066-4197. PMID 34555285. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ↑ Brown, Eryn (27 April 2022). "Mining museums' genomic treasures". Knowable Magazine. Annual Reviews. doi:10.1146/knowable-042522-2. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ↑ "US Fish and Wildlife Service Species Profile". Ecos.fws.gov. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Brennan, Deborah Sullivan (July 29, 2013). "The Big Burn: Scientists say Mountain fire ecologically necessary in area with a century of overgrowth". San Diego Union Tribune.

- ↑ Runte p. 86

- 1 2 3 Grinnell, Joseph; Storer, Tracy Irwin (1916). "Animal Life as an Asset to National Parks". Science. 44 (1133): 375–80. Bibcode:1916Sci....44..375G. doi:10.1126/science.44.1133.375. hdl:2027/hvd.32044106290034. PMID 17838357.

- ↑ Macintosh, Barry Interpretation in the National Park Service: a Historical Perspective. Online book History Division, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. 1986

- ↑ Runte, p. 92

- ↑ "Harold C. Bryant". Archived from the original on February 3, 2006. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). rpts.tamu.edu - ↑ Cameron, Jenks The Bureau of Biological Survey-Its History, Activities, and Organization, Ayer Publishing 1974 p. 47

- ↑ Steinhart, Peter The Company of Wolves Random House Publishers 1996 p. 242

- ↑ "Mammal collections database Museum of Vertebrate Zoology". Arctos.database.museum. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Grinnell and Storer, 1924, p. 85

- ↑ "Mammal collections database Museum of Vertebrate Zoology". Arctos.database.museum. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Schwartz, M. K.; Aubry, Keith B.; McKelvey, Kevin S.; Pilgrim, Kristine L.; Copeland, Jeffrey P.; Squires, John R.; Inman, Robert M.; Wisely, Samantha M.; Ruggiero, Leonard F. (2007). "Inferring Geographic Isolation of Wolverines in California Using Historical DNA" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Management. 71 (7): 2170–2179 (Table 1). doi:10.2193/2007-026. JSTOR 4496327. S2CID 35396299.

- ↑ Runte p. 88

- ↑ Runte p. 90

- ↑ Grinnell, 1937 p. 270

- ↑ "Sierra Club, Santa Lucia Chapter "Point Lobos State Reserve"". Santalucia.sierraclub.org. Archived from the original on 2012-08-26. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "Point Lobos State Park homepage". Archived from the original on October 5, 2010. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). pointlobos.org - ↑ "Hasting Brochure 1985" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-07. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "Berkeley Daily Gazette April 10, 1940 "Naturalists Form Society at U.C."". 1940-04-10. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "Online Archive of California, "Guide to the Grinnell Naturalists Society Records, 1940-1952"". Oac.cdlib.org. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Richmond, Charles W. (1922). "In Memoriam: William, Palmer" (PDF). The Auk. 39 (3): 305–321 (311). doi:10.2307/4073428. JSTOR 4073428.

- ↑ Barber, Rachel (10 February 2019). "Peregrine falcons return to Campanile, will be livestreamed 24/7". The Daily Californian. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ↑ Christopher Scharpf & Kenneth J. Lazara (22 September 2018). "Order SYNGNATHIFORMES: Families DACTYLOPTERIDAE, PEGASIDAE, CALLIONYMIDAE, DRACONETTIDAE and MULLIDAE". The ETYFish Project Fish Name Etymology Database. Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

Cited literature

- Grinnell, Joseph Gold Hunting in Alaska 1901

- Grinnell, Joseph and Tracy Storer Animal Life in the Yosemite 1924

- Grinnell, Joseph, Jean M. Linsdale and Joseph S. Dixon Fur-bearing Mammals of California 1937

- Runte, Alfred (1990). Joseph Grinnell and Yosemite: Rediscovering the legacy of a California conservationist. University of California Press. pp. 85–96. ISBN 978-0-520-08160-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Stein, Barbara On Her Own Terms, University of California Press, 2001, ISBN 0520227263

External links

- Works by Joseph Grinnell at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Joseph Grinnell at Internet Archive

- High Country News magazine, "The Ghosts of Yosemite – scientists from the past bring us a message about the future" by Michelle Nijhuis. October 17, 2005

- Museum of Vertebrate Zoology website.

- Guide to the Joseph and Hilda Wood Grinnell Papers and Guide to the Joseph Grinnell Papers at The Bancroft Library

- Western Kentucky University

- Works by Joseph Grinnell at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)