Judas Iscariot | |

|---|---|

Judas Iscariot (right), retiring from the Last Supper, painting by Carl Bloch, late 19th century | |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1st century |

| Died | AD 31 |

| Cause of death | Suicide by hanging |

| Parent | Simon Iscariot (father) |

| Known for | Betraying Jesus |

Judas Iscariot (/ˈdʒuːdəs ɪˈskæriət/; Biblical Greek: Ἰούδας Ἰσκαριώτης Ioúdas Iskariṓtēs; Hebrew: יהודה איש קריות Yəhūda ʾĪš Qǝrīyyōṯ; died c. 30 – c. 33 AD) was—according to Christianity's four canonical gospels—a disciple and one of the original Twelve Apostles of Jesus Christ. Judas betrayed Jesus to the Sanhedrin in the Garden of Gethsemane by kissing him on the cheek and addressing him as "master" to reveal his identity in the darkness to the crowd who had come to arrest him.[1] Like Brutus, his name is often used synonymously with betrayal or treason.

The Gospel of Mark gives no motive for Judas' betrayal but does present Jesus predicting it at the Last Supper, an event also described in all the other gospels. The Gospel of Matthew 26:15 states that Judas committed the betrayal in exchange for thirty pieces of silver. The Gospel of Luke 22:3 and the Gospel of John 13:27 suggest that he was possessed by Satan. According to Matthew 27:1–10, after learning that Jesus was to be crucified, Judas attempted to return the money he had been paid for his betrayal to the chief priests and hanged himself.[2] The priests used the money to buy a field to bury strangers in, which was called the "Field of Blood" because it had been bought with blood money. The Book of Acts 1:18 quotes Peter as saying that Judas used the money to buy the field himself and, he "[fell] headlong... burst asunder in the midst, and all his bowels gushed out." His place among the Twelve Apostles was later filled by Matthias.

Due to his notorious role in all the gospel narratives, Judas remains a controversial figure in Christian history. His betrayal is seen as setting in motion the events that led to Jesus' crucifixion and resurrection, which, according to traditional Christian theology brought salvation to humanity. The Gnostic Gospel of Judas—rejected by the proto-orthodox Church as heretical—portrays Judas' actions as done in obedience to instructions given to him by Jesus, and that he alone amongst the disciples knew Jesus' true teachings. Since the Middle Ages, Judas has sometimes been portrayed as a personification of the Jewish people, and his betrayal has been used to justify Christian antisemitism.[3]

Historicity

Although Judas Iscariot's historical existence is generally widely accepted among secular historians,[4][5][6][7] this relative consensus has not gone entirely unchallenged.[5] The earliest possible allusion to Judas comes from the First Epistle to the Corinthians 11:23–24, in which Paul the Apostle does not mention Judas by name[8][9] but uses the passive voice of the Greek word paradídōmi (παραδίδωμι), which most Bible translations render as "was betrayed":[8][9] "...the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took a loaf of bread..."[8] Nonetheless, some biblical scholars argue that the word paradídōmi should be translated as "was handed over".[8][9] This translation could still refer to Judas,[8][9] but it could also instead refer to God metaphorically "handing Jesus over" to the Romans.[8]

In his book Antisemitism and Modernity (2006), the Jewish scholar Hyam Maccoby suggests that, in the New Testament, the name "Judas" was constructed as an attack on the Judaeans or on the Judaean religious establishment held responsible for executing Jesus.[10][11] In his book The Sins of Scripture (2009), John Shelby Spong concurs with this argument,[12][13] insisting, "The whole story of Judas has the feeling of being contrived ... The act of betrayal by a member of the twelve disciples is not found in the earliest Christian writings. Judas is first placed into the Christian story by the Gospel of Mark (3:19), who wrote in the early 70s CE."[12]

Most scholars reject these arguments for non-historicity,[6][14][15][16] noting that there is nothing in the gospels to associate Judas with Judeans except his name, which was an extremely common one for Jewish men during the first century,[14][17][9] and that numerous other figures named "Judas" are mentioned throughout the New Testament, none of whom are portrayed negatively.[14][17][9] Positive figures named Judas mentioned in the New Testament include the prophet Judas Barsabbas (Acts 15:22–33), Jesus' brother Jude (Mark 6:3; Matt 13:55; Jude 1), and the apostle Judas the son of James (Luke 6:14–16; Acts 1:13; John 14:22).[14]

Life

Name and background

_-_James_Tissot_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The name "Judas" (Ὶούδας) is a Greek rendering of the Hebrew name Judah (יהודה, Yehûdâh, Hebrew for "praise or praised"), which was an extremely common name for Jewish men during the first century AD, due to the renowned hero Judas Maccabeus.[17][9] Consequently, numerous other figures with this name are mentioned throughout the New Testament.[14][17][9] In the Gospel of Mark 3:13–19, which was written in the mid-60s or early 70s AD, Judas Iscariot is the only apostle named "Judas".[9] Matthew 10:2–4 shares this portrayal.[9] The Gospel of Luke 6:12–19, however, replaces the apostle whom Mark and Matthew call "Thaddeus" with "Judas son of James".[9] Peter Stanford suggests that this renaming may represent an effort by the author of the Gospel of Luke to create a "good Judas" in contrast to the betrayer Judas Iscariot.[9]

Judas' epithet "Iscariot" (Ὶσκάριωθ or Ὶσκαριώτης), which distinguishes him from the other people named "Judas" in the gospels, is usually thought to be a Greek rendering of the Hebrew phrase איש־קריות, (Κ-Qrîyôt), meaning "the man from Kerioth".[17][9][18] This interpretation is supported by the statement in the Gospel of John 6:71 that Judas was "the son of Simon Iscariot".[9] Nonetheless, this interpretation of the name is not fully accepted by all scholars.[17][9] One of the most popular alternative explanations holds that "Iscariot" (ܣܟܪܝܘܛܐ, 'Skaryota' in Syriac Aramaic, per the Peshitta text) may be a corruption of the Latin word sicarius, meaning "dagger man",[17][9][19][20] which referred to a member of the Sicarii (סיקריים in Aramaic), a group of Jewish rebels who were known for committing acts of terrorism in the 40s and 50s AD by assassinating people in crowds using long knives hidden under their cloaks.[17][9] This interpretation is problematic, however, because there is nothing in the gospels to associate Judas with the Sicarii,[9] and there is no evidence that the cadre existed during the 30s AD when Judas was alive.[21][9]

A possibility advanced by Ernst Wilhelm Hengstenberg is that "Iscariot" means "the liar" or "the false one", from the Hebrew איש-שקרים. C. C. Torrey suggests instead the Aramaic form שְׁקַרְיָא or אִשְׁקַרְיָא, with the same meaning.[22][23] Stanford rejects this, arguing that the gospel writers follow Judas' name with the statement that he betrayed Jesus, so it would be redundant for them to call him "the false one" before immediately stating that he was a traitor.[9] Some have proposed that the word derives from an Aramaic word meaning "red color", from the root סקר.[24] Another hypothesis holds that the word derives from one of the Aramaic roots סכר or סגר. This would mean "to deliver", based on the Septuagint rendering of Isaiah 19:4—a theory advanced by J. Alfred Morin.[23] The epithet could also be associated with the manner of Judas' death, hanging. This would mean Iscariot derives from a kind of Greek-Aramaic hybrid: אִסְכַּרְיוּתָא, Iskarioutha, meaning "chokiness" or "constriction". This might indicate that the epithet was applied posthumously by the remaining disciples, but Joan E. Taylor has argued that it was a descriptive name given to Judas by Jesus, since other disciples such as Simon Peter/Cephas (Kephas "rock") were also given such names.[23]

Role as an apostle

Although the canonical gospels frequently disagree on the names of some of the minor apostles,[25] all four of them list Judas Iscariot as one of them.[25][9] The Synoptic Gospels state that Jesus sent out "the twelve" (including Judas) with power over unclean spirits and with a ministry of preaching and healing: Judas clearly played an active part in this apostolic ministry alongside the other eleven.[26] However, in the Gospel of John, Judas' outlook was differentiated—many of Jesus' disciples abandoned him because of the difficulty of accepting his teachings, and Jesus asked the twelve if they would also leave him. Simon Peter spoke for the twelve: "Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life," but Jesus observed then that despite the fact that he himself had chosen the twelve, one of them (unnamed by Jesus, but identified by the narrator) was "a devil" who would betray him.[27]

One of the best-attested and most reliable statements made by Jesus in the gospels comes from the Gospel of Matthew 19:28, in which Jesus tells his apostles: "in the new world, when the Son of Man shall sit on his glorious throne, you will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the Twelve Tribes of Israel."[25] New Testament scholar Bart D. Ehrman concludes, "This is not a tradition that was likely to have been made up by a Christian later, after Jesus' death—since one of these twelve had abandoned his cause and betrayed him. No one thought that Judas Iscariot would be seated on a glorious throne in the Kingdom of God. That saying, therefore appears to go back to Jesus, and indicates, then, that he had twelve close disciples, whom he predicted would reign in the coming Kingdom."[25]

Matthew directly states that Judas betrayed Jesus for a bribe of "thirty pieces of silver"[28][29] by identifying him with a kiss—"the kiss of Judas"—to arresting soldiers of the High Priest Caiaphas, who then turned Jesus over to Pontius Pilate's soldiers. Mark's Gospel states that the chief priests were looking for a way to arrest Jesus. They decided not to do so during the feast [of the Passover], since they were afraid that people would riot;[30] instead, they chose the night before the feast to arrest him. According to Luke's account, Satan entered Judas at this time.[31]

According to the account in the Gospel of John, Judas carried the disciples' money bag or box (γλωσσόκομον, glōssokomon),[32] but the Gospel of John makes no mention of the thirty pieces of silver as a fee for betrayal. The evangelist comments in John 12:5–6 that Judas spoke fine words about giving money to the poor, but the reality was "not that he cared for the poor, but [that] he was a thief, and had the money box; and he used to take what was put in it." However, in John 13:27–30, when Judas left the gathering of Jesus and his disciples with betrayal in mind,[33] some [of the disciples] thought that Judas might have been leaving to buy supplies or on a charitable errand.

Ehrman argues that Judas' betrayal "is about as historically certain as anything else in the tradition",[4][17] pointing out that the betrayal is independently attested in the Gospel of Mark, in the Gospel of John, and in the Book of Acts.[4][17] Ehrman also contends that it is highly unlikely that early Christians would have made up the story of Judas' betrayal, since it reflects poorly on Jesus' judgement in choosing him as an apostle.[4][34] Nonetheless, Ehrman argues that what Judas actually told the authorities was not Jesus' location, but rather Jesus' secret teaching that he was the Messiah.[4] This, he holds, explains why the authorities did not try to arrest Jesus prior to Judas' betrayal.[4] John P. Meier sums up the historical consensus, stating, "We only know two basic facts about [Judas]: (1) Jesus chose him as one of the Twelve, and (2) he handed over Jesus to the Jerusalem authorities, thus precipitating Jesus' execution."[35]

Death

Many different accounts of Judas' death have survived from antiquity, both within and outside the New Testament.[36][37] Matthew 27:1–10 states that after learning that Jesus was to be crucified, Judas was overcome by remorse and attempted to return the 30 pieces of silver to the priests, but they would not accept them because they were blood money, so he threw them on the ground and left. Afterwards, he committed suicide by hanging himself[38] according to Mosaic law (Deuteronomy 21:22–23[39]). The priests then used the money to buy a potter's field, which became known as Akeldama (חקל דמא – khakel dama) – the Field of Blood – because it had been bought with blood money.[38] Acts 1:18 states that Judas used the money to buy a field,[38][40] and "[fell] headlong... burst asunder in the midst, and all his bowels gushed out."[38] In this account, Judas' death is apparently by accident,[38] and he shows no signs of remorse.[38]

The early Church Father Papias of Hierapolis records in his Expositions of the Sayings of the Lord (which was probably written around 100 AD) that Judas was afflicted by God's wrath;[41][42] his body became so enormously bloated that he could not pass through a street with buildings on either side.[41][42] His face became so swollen that a doctor could not even identify the location of his eyes using an optical instrument.[41] Judas' genitals became enormously swollen and oozed with pus and worms.[41] Finally, he killed himself on his own land by pouring out his innards onto the ground,[41][42] which stank so horribly that, even in Papias' own time a century later, people still could not pass the site without holding their noses.[41][42] This story was well known among Christians in antiquity[42] and was often told in competition with the two conflicting stories from the New Testament.[42]

According to the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, which was probably written in the fourth century AD, Judas was overcome with remorse[43] and went home to tell his wife, who was roasting a chicken on a spit over a charcoal fire, that he was going to kill himself, because he knew Jesus would rise from the dead and, when he did, he would punish him.[43] Judas' wife laughed and told him that Jesus could no more rise from the dead than he could resurrect the chicken she was cooking.[36] Immediately, the chicken was restored to life and began to crow.[41] Judas then ran away and hanged himself.[41] In the apocryphal Gospel of Judas, Judas has a vision of the disciples stoning and persecuting him.[44]

The discrepancy between the two different accounts of Judas' death in Matthew 27:1–10 and Acts 1:18 has proven to be a serious challenge to those who support the idea of Biblical inerrancy.[43][42] This problem was one of the points leading C. S. Lewis, for example, to reject the view "that every statement in Scripture must be historical truth".[45] Nonetheless, various attempts at harmonization have been suggested.[42] Generally they have followed literal interpretations such as that of Augustine of Hippo, which suggest that these simply describe different aspects of the same event—that Judas hanged himself in the field, and the rope eventually snapped and the fall burst his body open,[46][47] or that the accounts of Acts and Matthew refer to two different transactions.[48] Some have taken the descriptions as figurative: that the "falling prostrate" was Judas in anguish,[lower-alpha 1] and the "bursting out of the bowels" is pouring out emotion.[lower-alpha 2]

Modern scholars reject these approaches.[49][50][51] Arie W. Zwiep states "neither story was meant to be read in light of the other"[42] and "the integrity of both stories as complete narratives in themselves is seriously disrespected when the two separate stories are being conflated into a third, harmonized version."[42] David A. Reed argues that the Matthew account is a midrashic exposition that allows the author to present the event as a fulfillment of prophetic passages from the Old Testament. They argue that the author adds imaginative details such as the thirty pieces of silver, and the fact that Judas hangs himself, to an earlier tradition about Judas' death.[52]

Matthew's description of the death as fulfilment of a prophecy "spoken through Jeremiah the prophet" has caused difficulties, since it does not clearly correspond to any known version of the Book of Jeremiah but does appear to refer to a story from the Book of Zechariah[53] which describes the return of a payment of thirty pieces of silver.[54] Even writers such as Jerome and John Calvin conclude that this was obviously an error.[lower-alpha 3] Evangelical theologian James R. White has suggested the misattribution arises from a supposed Jewish practice of using the name of a major prophet to refer to the whole content of the scroll group, including books written by minor prophets placed in the same grouping.[55]

Some scholars have suggested that the writer may also have had a passage from Jeremiah in mind,[56] such as chapters 18:1–4 and 19:1–13 which refer to a potter's jar and a burial place, and chapter 32:6–15 which refers to a burial place and an earthenware jar.[57] Raymond Brown suggests "the most plausible [explanation] is that Matthew 27:9–10 is presenting a mixed citation with words taken both from Zechariah and Jeremiah, and ... he refers to that combination by one name. Jeremiah 18–9 concerns a potter (18:2–; 19:1), a purchase (19:1), the Valley of Hinnom (where the Field of Blood is traditionally located, 19:2), 'innocent blood' (19:4), and the renaming of a place for burial (19:6, 11); and Jer 32:6–5 tells of the purchase of a field with silver."[58]

Classicist Glenn W. Most suggests that Judas' death in Acts can be interpreted figuratively, writing that πρηνὴς γενόμενος should be translated as saying his body went prone, rather than falling headlong, and the spilling of the entrails is meant to invoke the imagery of dead snakes and their burst-open bellies. Hence Luke was stating that Judas took the body posture of a snake and died like one.[59] However, the Catholic biblical scholar John L. McKenzie states "This passage probably echoes the fate of the wicked in..." the Deuterocanonical book Wisdom of Solomon 4:19:[60] "... [the Lord] will dash them speechless to the ground, and shake them from the foundations; they will be left utterly dry and barren, and they will suffer anguish, and the memory of them will perish."[61]

Betrayal of Jesus

_Cropped.jpg.webp)

There are several explanations as to why Judas betrayed Jesus.[62] In the earliest account, in the Gospel of Mark, when he goes to the chief priests to betray Jesus, he is offered money as a reward, but it is not clear that money is his motivation.[63] In the Gospel of Matthew account, on the other hand, he asks what they will pay him for handing Jesus over.[64] In the Gospel of Luke[65] and the Gospel of John,[66] the devil enters into Judas, causing him to offer to betray Jesus. The Gospel of John account has Judas complaining that money has been spent on expensive perfumes to anoint Jesus which could have been spent on the poor, but adds that he was the keeper of the apostles' purse and used to steal from it.[67] According to some, Judas thought he could get the money for betraying Jesus without Him being killed as He would escape like He had done many times before.[68][69][70][71]

One suggestion has been that Judas expected Jesus to overthrow Roman rule of Judea. In this view, Judas is a disillusioned disciple betraying Jesus not so much because he loved money, but because he loved his country and thought Jesus had failed it.[62] Another is that Jesus was causing unrest likely to increase tensions with the Roman authorities and they thought he should be restrained until after the Passover, when everyone had gone back home and the commotion had died down.[72]

The gospels suggest that Jesus foresaw (John 6:64, Matthew 26:25) and allowed Judas' betrayal (John 13:27–28).[73] One explanation is that Jesus allowed the betrayal because it would allow God's plan to be fulfilled. Another is that regardless of the betrayal, Jesus was ultimately destined for crucifixion.[74] In April 2006, a Coptic papyrus manuscript titled the Gospel of Judas from 200 AD was translated, suggesting that Jesus told Judas to betray him,[75] although some scholars question the translation.[76][77] Nevertheless, the Gospel of Judas is an apocryphal Gnostic gospel composed in the 2nd century, and some scholars agree that it contains no real historical information.[78]

Judas is the subject of philosophical writings. Origen of Alexandria, in his Commentary on John's Gospel, reflects on Judas' interactions with the other apostles and Jesus' confidence in him prior to his betrayal.[79] Other philosophical reflections on Judas include The Problem of Natural Evil by Bertrand Russell and "Three Versions of Judas", a short story by Jorge Luis Borges. They allege various problematic ideological contradictions with the discrepancy between Judas' actions and his eternal punishment. Bruce Reichenbach argues that if Jesus foresees Judas' betrayal, then the betrayal is not an act of free will[80] and therefore should not be punishable. Conversely, it is argued that just because the betrayal was foretold, it does not prevent Judas from exercising his own free will in this matter.[81] Other scholars argue that Judas acted in obedience to God's will.[82] The gospels suggest that Judas is apparently bound up with the fulfillment of God's purposes (John 13:18, John 17:12, Matthew 26:23–25, Luke 22:21–22, Matt 27:9–10, Acts 1:16, Acts 1:20),[73] yet "woe is upon him", and he would "have been better unborn" (Matthew 26:23–25). The difficulty inherent in the saying is its paradox: if Judas had not been born, the Son of Man would apparently no longer do "as it is written of him." The consequence of this apologetic approach is that Judas' actions come to be seen as necessary and unavoidable, yet leading to condemnation.[83] Another explanation is that Judas' birth and betrayal did not necessitate the only way the Son of Man could have suffered and been crucified. The earliest churches believed "as it is written of him" to be prophetic, fulfilling Scriptures such as that of the suffering servant in Isaiah 52–53 and the righteous one in Psalm 22, which do not require betrayal (at least by Judas) as the means to the suffering. Regardless of any necessity, Judas is held responsible for his act (Mark 14:21; Luke 22:22; Matt 26:24).[84]

In his 1965 book The Passover Plot, British New Testament scholar Hugh J. Schonfield suggests that the crucifixion of Christ was a conscious re-enactment of Biblical prophecy and that Judas acted with the full knowledge and consent of Jesus in "betraying" him to the authorities. The book has been variously described as "factually groundless",[85] based on "little data" and "wild suppositions",[86] "disturbing", and "tawdry".[87]

Damnation to Hell

It is speculated that Judas' damnation, which seems possible from the gospels' texts,[88][89] may not stem from his betrayal of Christ but from the despair which caused him to subsequently commit suicide.[90] This is confirmed in Cornelius à Lapide's famous commentary, in which he writes that, by hanging himself, "Judas then added to his former sin the further sin of despair. It was not a more heinous sin, but one more fatal to himself, as thrusting him down to the very depths of hell. He might, on his repentance, have asked (and surely have obtained) pardon of Christ. But, like Cain, he despaired of forgiveness."[91] The concept that Judas despaired of God's forgiveness is reiterated by Rev. A. Jones in his contribution to a mid-20th century Catholic commentary: "Filled with remorse (not true 'repentance' because empty of hope) [Judas] sought to dissociate himself from the affair..." before committing suicide (cf. Matthew 27:3–5).[92] However, some believed that Judas "hanged himself thinking to precede Jesus into hades and there to plead for his own salvation."[68]

Protestant theologians

Erasmus believed that Judas was free to change his intention, but Martin Luther argued in rebuttal that Judas' will was immutable. John Calvin states that Judas was predestined to damnation but writes on the question of Judas' guilt: "surely in Judas' betrayal, it will be no more right, because God himself willed that his son be delivered up and delivered him up to death, to ascribe the guilt of the crime to God than to transfer the credit for redemption to Judas."[93] Karl Daub, in his book Judas Ischariot, writes that Judas should be considered "an incarnation of the devil" for whom "mercy and blessedness are alike impossible."[94]

The Geneva Bible contains several additional notes concerning Judas Iscariot within its commentaries. In the Gospel of Matthew, after the Sanhedrin condemns Jesus Christ to death, are added the comments concerning Judas: "...late repentance brings desperation" (cf. Mat. 27:3), and "Although he abhor his sins, yet is he not displeased there with, but despairs in God's mercies, and seeks his own destruction" (cf. Mat. 27:4). Furthermore, within Acts of the Apostles is the comment, "Perpetual infamy is the reward of all such as by unlawfully gotten goods buy anything" when Judas purchased the "Field of Blood" with the 30 pieces of silver (cf Acts 1:18).[95] Obviously, the commentator had no doubt about the fate of Judas.

Catholic doctrine

The Catholic Church took no specific view concerning the damnation of Judas during Vatican II; speaking in generalities, that Council stated, "[We] must be constantly vigilant so that ... we may not be ordered to go into the eternal fire (cf. Mk. 25, 41) like wicked and slothful servants (cf. Mk. 25, 26), into the exterior darkness where 'there will be the weeping and the gnashing of teeth' (Mt. 22, 13 and 25, 30)."[96] The Vatican only proclaims individuals' Eternal Salvation through the Canon of Saints. There is no 'Canon of the Damned.'

Thus, there is a school of thought within the Catholic Church that it is unknown whether Judas Iscariot is in Hell; for example, David Endres, writing in The Catholic Telegraph, cites Catechism of the Catholic Church §597 for the inability to make any determination whether Judas is in Hell.[97] However, while that section of the catechism does instruct Catholics that the personal sin of Judas is unknown but to God, that statement is within the context that the Jewish people have no collective responsibility for Jesus' death: "... the Jews should not be spoken of as rejected or accursed as if this followed from holy Scripture."[98] This seems to be defining a different doctrinal point (i.e., the relationship of Catholics with Jewish people), rather than making any sort of decision concerning Judas' particular judgment.

However, Vatican II was a pastoral rather than dogmatic council, and Christopher J. Malloy (assistant professor of theology at the Constantin College of Liberal Arts at University of Dallas) states that Ludwig Ott's reference book Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma should be regarded, "... as being current on the infallible teachings of the Church taught by the extraordinary Magisterium."[99] That reference book identifies Judas Iscariot as an example of a person receiving punishment as a particular judgment.[100]

The Catechism of the Council of Trent, which mentions Judas Iscariot several times, wrote that he possessed "motive unworthy" when he entered the priesthood and was thus sentenced to "eternal perdition."[101] Furthermore, Judas is given as an example of a sinner that will "despair of mercy" because he looked "...on God as an avenger of crime and not, also, as a God of clemency and mercy."[102] All of the council's decrees were confirmed by Pope Pius IV on 28 January 1564.[103] Thus, an ecumenical council, confirmed by the Magisterium of a Pope, affirmed that Judas Iscariot was condemned to Hell. The Council of Trent continued the tradition of the early Church fathers, such as Pope Leo I ("...had [Judas] not thus denied His omnipotence, he would have obtained His mercy..."[104]), and Pope Gregory I ("The godless betrayer, shutting his mind to all these things, turned upon himself, not with a mind to repent, but in a madness of self destruction: ... even in the act of dying sinned unto the increase of his own eternal punishment."[105])

Also, the Decree of Justification, promulgated during Session VI of the Council of Trent, states in Cannon 6, "If anyone shall say that it is not in the power of man to make his ways evil, but that God produces evil as well as the good works, not only by permission, but also properly and of Himself, so that the betrayal of Judas is not less His own proper work than the vocation of Paul; let him be anathema."[106] Here, the Council is making it clear that Judas exercised his own free will to commit the betrayal of Jesus Christ, rather than being predestined by God. Also, by contrasting the actions of Judas to those of Paul, the implication is that Judas is the opposite of a saint (i.e., damned).

Liturgical institutions are part of the expressions of Sacred Tradition of the Catholic Church.[107] Within the 1962 Roman Missal for the Tridentine Latin Mass, the Collect for Holy Thursday states: "O God, from whom Judas received the punishment of his guilt, and the thief the reward of his confession ... our Lord Jesus Christ gave to each a different recompense according to his merits..."[108] In his commentary on the Liturgical Year, Abbot Gueranger, O.S.B. states that the Collect reminds Catholics that both Judas and the good thief are guilty, "...and yet, the one is condemned, the other pardoned."[109] Thus, the Tridentine Latin Mass, as currently celebrated, continues to foster the tradition within the Catholic Church that Judas was punished.

Other

In the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, Judas is punished for all eternity in the ninth circle of Hell: in it, he is devoured by Lucifer, alongside Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus (leaders of the group of senators that assassinated Julius Caesar). The innermost region of the ninth circle is reserved for traitors of masters and benefactors and is named Judecca, after Judas.

In his 1969 book Theologie der Drei Tage (English translation: Mysterium Paschale), Hans Urs von Balthasar emphasizes that Jesus was not betrayed but surrendered and delivered up by himself, since the meaning of the Greek word used by the New Testament, paradidonai (παραδιδόναι, Latin: tradere), is unequivocally "handing over of self".[110][111] In the "Preface to the Second Edition", Balthasar takes a cue from Revelation 13:8[112] (Vulgate: agni qui occisus est ab origine mundi, NIV: "the Lamb who was slain from the creation of the world") to extrapolate the idea that God as "immanent Trinity" can endure and conquer godlessness, abandonment, and death in an "eternal super-kenosis".[113][114] ). A Catholic priest, Richard Neuhaus, an admitted student of Balthasar, argues that it is unknown if Judas is in Hell, and it is also possible that Hell could be empty.[115] However, Cristiani considers that Balthasar and Neuhaus are merely recycling the error of Origenism which includes denying the eternity of Hell "...by a general rehabilitation of the damned, including, apparently, Satan."[116] This error, while not considered a formal heresy, was condemned at a synod in 548 AD, which was subsequently confirmed by Pope Vigilius.[117]

Role in apocrypha

Judas has been a figure of great interest to esoteric groups, such as many Gnostic sects. Irenaeus records the beliefs of one Gnostic sect, the Cainites, who believed that Judas was an instrument of the Sophia, Divine Wisdom, thus earning the hatred of the Demiurge. His betrayal of Jesus thus was a victory over the materialist world. The Cainites later split into two groups, disagreeing over the ultimate significance of Jesus in their cosmology.

Syriac Infancy Gospel

The Syriac Infancy Gospel[118] borrows from some of the different versions of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas.[119] However, it adds many of its own tales, probably from local legends, including one of Judas. This pseudepigraphic work tells how Judas, as a boy, was possessed by Satan, who caused him to bite himself or anyone else present. In one of these attacks, Judas bit the young Jesus in the side; and, by touching Him, Satan was exorcised. It further states that the side which Judas supposedly bit was the same side that was pierced by the Holy Lance at the Crucifixion.[120]

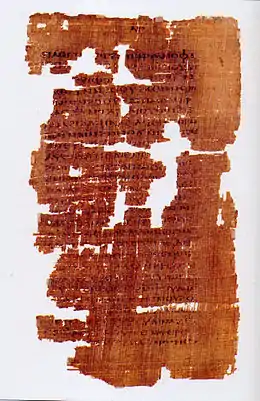

Gospel of Judas

During the 1970s, a Coptic papyrus codex (book) was discovered near Beni Masah, Egypt. It appeared to be a 3rd- or 4th-century-AD copy of a 2nd-century original,[121][122] relating a series of conversations in which Jesus and Judas interact and discuss the nature of the universe from a Gnostic viewpoint. The discovery was given dramatic international exposure in April 2006 when the US National Geographic magazine published a feature article entitled "The Gospel of Judas" with images of the fragile codex and analytical commentary by relevant experts and interested observers (but not a comprehensive translation). The article's introduction stated: "An ancient text lost for 1,700 years says Christ's betrayer was his truest disciple."[123] The article points to some evidence that the original document was extant in the 2nd century: "Around A.D. 180, Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyon in what was then Roman Gaul, wrote a massive treatise called Against Heresies [in which he attacked] a 'fictitious history,' which 'they style the Gospel of Judas.'"[124]

Before the magazine's edition was circulated, other news media gave exposure to the story, abridging and selectively reporting it.[75]

In December 2007, April DeConick asserted that the National Geographic's translation is badly flawed: "For example, in one instance the National Geographic transcription refers to Judas as a 'daimon,' which the society's experts have translated as 'spirit.' However, the universally accepted word for 'spirit' is 'pneuma'—in Gnostic literature "daimon" is always taken to mean 'demon.'"[125] The National Geographic Society responded that "Virtually all issues April D. DeConick raises about translation choices are addressed in footnotes in both the popular and critical editions."[126] In a later review of the issues and relevant publications, critic Joan Acocella questioned whether ulterior intentions had not begun to supersede historical analysis, e.g., whether publication of The Gospel of Judas could be an attempt to roll back ancient anti-semitic imputations. She concluded that the ongoing clash between scriptural fundamentalism and attempts at revision were childish because of the unreliability of the sources. Therefore, she argued, "People interpret, and cheat. The answer is not to fix the Bible but to fix ourselves."[127] Other scholars have questioned the initial translation and interpretation of the Gospel of Judas by the National Geographic team of experts.[76]

Gospel of Barnabas

According to medieval copies (the earliest copies from the 15th century) of the Gospel of Barnabas it was Judas, not Jesus, who was crucified on the cross. This work states that Judas' appearance was transformed to that of Jesus, when the former, out of betrayal, led the Roman soldiers to arrest Jesus who by then was ascended to the heavens. This transformation of appearance was so identical that the masses, followers of Christ, and even the Mother of Jesus, Mary, initially thought that the one arrested and crucified was Jesus himself. The gospel then mentions that after three days since burial, Judas' body was stolen from his grave, and then the rumors spread of Jesus being risen from the dead. When Jesus was informed in the third heaven about what happened, he prayed to God to be sent back to the earth, and descended and gathered his mother, disciples, and followers, and told them the truth of what happened. He then ascended back to the heavens, and will come back at the end of times as a just king.

This gospel is considered by the majority of Christians to be late and pseudepigraphical; however, some academics suggest that it may contain some remnants of an earlier apocryphal work (perhaps Gnostic, Ebionite, or Diatessaronic), redacted to bring it more in line with Islamic doctrine. Some Muslims consider the surviving versions as transmitting a suppressed apostolic original. Some Islamic organizations cite it in support of the Islamic view of Jesus.

Representations and symbolism

Although the sanctification of the instruments of the Passion of Jesus (the so-called Arma Christi), that slowly accrued over the course of the Middle Ages in Christian symbolism and art, also included the head and lips of Judas,[128] the term Judas has entered many languages as a synonym for betrayer, and Judas has become the archetype of the traitor in Western art and literature. Judas is given some role in virtually all literature telling the Passion story and appears in numerous modern novels and movies.

In the Eastern Orthodox hymns of Holy Wednesday (the Wednesday before Pascha), Judas is contrasted with the woman who anointed Jesus with expensive perfume and washed his feet with her tears. The hymns of Holy Wednesday contrast these two figures, encouraging believers to avoid the example of the fallen disciple and instead to imitate Mary's example of repentance. Also, Wednesday is observed as a day of fasting from meat, dairy products, and olive oil throughout the year in memory of the betrayal of Judas. The prayers of preparation for receiving the Eucharist also make mention of Judas' betrayal: "I will not reveal your mysteries to your enemies, neither like Judas will I betray you with a kiss, but like the thief on the cross I will confess you."

Judas Iscariot is often shown with red hair in Spanish culture[129][130][131] and by William Shakespeare.[131][132] The practice is comparable to the Renaissance portrayal of Jews with red hair, which was then regarded as a negative trait and which may have been used to correlate Judas Iscariot with contemporary Jews.[133]

In paintings depicting the Last Supper, Judas is occasionally depicted with a dark-colored halo (contrasting with the lighter halos of the other apostles) to signify his former status as an apostle. More commonly, however, he is the only one at the table without one. Some church stained-glass windows show him with a dark halo such as in one of the windows of the Church of St John the Baptist, Yeovil.

Art and literature

- Judas is the subject of one of the oldest surviving English ballads, which dates from the 13th century. In the ballad "Judas", the blame for the betrayal of Christ is placed on Judas' sister.[134]

- One of the most famous depictions of Judas Iscariot and his kiss of betrayal of Jesus is The Taking of Christ by Italian Baroque artist Caravaggio, painted in 1602.[135]

- In Memoirs of Judas (1867) by Ferdinando Petruccelli della Gattina, he is seen as a leader of the Jewish revolt against the rule of Romans.[136] Edward Elgar's oratorio, The Apostles, depicts Judas as wanting to force Jesus to declare his divinity and establish the kingdom on earth.[137]

- In Trial of Christ in Seven Stages (1909) by John Brayshaw Kaye, the author did not accept the idea that Judas intended to betray Christ, and the poem is a defence of Judas, in which he adds his own vision to the biblical account of the story of the trial before the Sanhedrin and Caiaphas.[138]

- In Mikhail Bulgakov's novel The Master and Margarita, Judas is paid by the high priest to testify against Jesus, who had been inciting trouble among the people of Jerusalem. After authorizing the crucifixion, Pilate suffers an agony of regret and turns his anger on Judas, ordering him assassinated.

- "Tres versiones de Judas" (English title: "Three Versions of Judas") is a short story by Argentine writer and poet Jorge Luis Borges; it was included in Borges' anthology Ficciones, published in 1944, and revolves around the main character's doubts about the canonical story of Judas who instead creates three alternative versions.[139]

- In The Last Days of Judas Iscariot (2005), a critically acclaimed play by Stephen Adly Guirgis, Judas is given a trial in Purgatory.[140]

See also

- Burning of Judas

- Judas' Ear mushroom (Auricularia auricula-judae)

- Judas goat

- Judas tree

- "Three Versions of Judas"

- Joseph ben Caiaphas – Jewish High Priest who organized the plot to kill Jesus.

- Valerius Gratus – Roman governor of Judea who appointed Joseph ben Caiaphas to become Jewish High Priest.

Explanatory notes

- ↑ The Monthly Christian Spectator 1851–1859 p. 459 "while some writers regard the account of Judas' death as simply figurative ..seized with preternatural anguish for his crime and its consequences his bowels gushed out."

- ↑ Clarence Jordan The Substance of Faith: and Other Cotton Patch Sermons p. 148 "Greeks thought of the bowels as being the seat of the emotions, the home of the soul. It's like saying that all of Judas' motions burst out, burst asunder."

- ↑ Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary (Eerdmans, 2004), p. 710; Jerome, Epistolae 57.7: "This passage is not found in Jeremiah but in Zechariah, in quite different words and a different order" "NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome – Christian Classics Ethereal Library". Archived from the original on 8 October 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2008.; John Calvin, Commentary on a Harmony of the Evangelists, Matthew, Mark and Luke, 3:177: "The passage itself plainly shows that the name of Jeremiah has been put down by mistake, instead of Zechariah, for in Jeremiah we find nothing of this sort, nor any thing that even approaches to it." "Commentary on Matthew, Mark, Luke – Volume 3 – Christian Classics Ethereal Library". Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2010..

Citations

- ↑ Matthew 26:14, Matthew 26:47, Mark 14:10, Mark 14:42, Luke 22:1, Luke 22:47, John 13:18, John 18:1

- ↑ "Matthew", The King James Bible, retrieved 15 June 2023

- ↑ Gibson, David (9 April 2006). "Anti-Semitism's Muse; Without Judas, History Might Have Hijacked Another Villain". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ehrman 1999, pp. 216–17.

- 1 2 Gubar 2009, pp. 31–33.

- 1 2 Stein, Robert H. (2009). "Criteria for the Gospels' Authenticity". In Paul Copan; William Lane Craig (eds.). Contending with Christianity's Critics: Answering New Atheists & Other Objectors. Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Publishing Group. p. 93. ISBN 978-0805449365.

- ↑ Meier, John P. (2005). "Criteria: How Do We Decide What Comes from Jesus?". In Dunn, James D.G.; McKnight, Scot (eds.). The Historical Jesus in Recent Research. Warsaw, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. pp. 127–28. ISBN 978-1575061009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gubar 2009, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Stanford 2015.

- ↑ Maccoby, Hyam (2006). Antisemitism and Modernity. London, England: Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 978-0415553889.

- ↑ Gubar 2009, p. 27.

- 1 2 Spong, John Shelby (2009). The Sins of Scripture. New York City: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0060778408.

- ↑ Gubar 2009, pp. 27–28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Oropeza, B.J. (2010). "Judas' Death and Final Destiny in the Gospels and Earliest Christian Writings". Neotestamentica. 44 (2): 342–61.

- ↑ Oropeza, B.J. (2011). In the Footsteps of Judas and Other Defectors: Apostasy in the New Testament Communities Volume 1:The Gospels, Acts, and Johannine Letters. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade/Wipf & Stock. pp. 149–50, 230.

- ↑ Gubar 2009, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Gubar 2009, p. 31.

- ↑ Bauckham, Richard (2006). Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 106. ISBN 978-0802874313.

- ↑ van Iersel, Bastiaan (1998). Mark: A Reader-Response Commentary. Danbury, Connecticut: Continuum International. p. 167. ISBN 978-1850758297.

- ↑ Roth bar Raphael, Andrew Gabriel-Yizkhak. Aramaic English New Testament (5 ed.). Netzari Press. ISBN 978-1934916421.; Sedro-Woolley, Wash.: Netzari Press, 2012), 278fn177.

- ↑ Brown, Raymond E. (1994). The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave: A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels v.1 pp. 688–92. New York: Doubleday/The Anchor Bible Reference Library. ISBN 0-385-49448-3; Meier, John P. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus (2001). v. 3, p. 210. New York: Doubleday/The Anchor Bible Reference Library. ISBN 0-385-46993-4.

- ↑ Torrey, Charles C. (1943). "The Name "Iscariot"". The Harvard Theological Review. 36 (1): 51–62. doi:10.1017/S0017816000029084. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 1507970. S2CID 162707224.

- 1 2 3 Taylor, Joan E. (2010). "The name 'Iskarioth' (Iscariot)". Journal of Biblical Literature. 129 (2): 367–83. doi:10.2307/27821024. JSTOR 27821024.

- ↑ Edwards, Katie (23 March 2016). "Why Judas was actually more of a saint, than a sinner". The Conversation. Melbourne, Australia: The Conversation Trust. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Gubar 2009, p. 30.

- ↑ See Mark 6:6; Matthew 10:5–10; and Luke 9:1

- ↑ John 6:67–71

- ↑ These "pieces of silver" were most likely intended to be understood as silver Tyrian shekels.

- ↑ Matthew 26:14

- ↑ Mark 14:1–2

- ↑ "BibleGateway.com – Passage Lookup: Luke 22:3". BibleGateway. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ↑ John 12:6andJohn 13:29

- ↑ John 13:2, Jerusalem Bible translation

- ↑ Gubar 2009, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Gubar 2009, p. 33.

- 1 2 Ehrman 2016, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Zwiep 2004, pp. 16–17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Zwiep 2004, p. 16.

- ↑ Smith, Barry D. (2010). The Meaning of Jesus' Death: Reviewing the New Testament's Interpretations. T&T Clark. p. 93. ISBN 978-0567670694.

- ↑ Ehrman, Bart D. (2008). The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: A New Look at Betrayer and Betrayed. Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-19-534351-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ehrman 2016, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Zwiep 2004, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 Ehrman 2016, p. 28.

- ↑ Gospel of Judas 44–45 Archived 11 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Letter to Clyde S. Kilby, 7 May 1959, quoted in Michael J. Christensen, C. S. Lewis on Scripture, Abingdon, 1979, Appendix A.

- ↑ Zwiep 2004, p. 109

- ↑ "Easton's Bible Dictionary: Judas". christnotes.org. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- ↑ "The purchase of "the potter's field," Appendix 161 of the Companion Bible". Archived from the original on 29 April 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ↑ Raymond E. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament, p. 114.

- ↑ Charles Talbert, Reading Acts: A Literary and Theological Commentary, Smyth & Helwys (2005) p. 15.

- ↑ Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary, Eerdmans (2004), p. 703.

- ↑ Reed, David A. (2005). "'Saving Judas': A Social Scientific Approach to Judas' Suicide in Matthew 27:3–10" (PDF). Biblical Theology Bulletin. 35 (2): 51–59. doi:10.1177/01461079050350020301. S2CID 144391749. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- ↑ Zechariah 11:12–13

- ↑ Vincent P. Branick, Understanding the New Testament and Its Message, (Paulist Press, 1998), pp. 126–28.

- ↑ James R. White, The King James Only Controversy, Bethany House Publishers (2009) pp. 213–15, 316.

- ↑ Donald Senior, The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew (Liturgical Press, 1985), pp. 107–08; Anthony Cane, The Place of Judas Iscariot in Christology (Ashgate Publishing, 2005), p. 50.

- ↑ Menken, Maarten JJ (2002). "The Old Testament Quotation in Matthew 27,9–10'". Biblica (83): 9–10. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008.

- ↑ Brown, Raymond (1998). The Death of the Messiah, From Gethsemane to the Grave, Volume 1: A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 912. ISBN 978-0300140095.

- ↑ Most, Glenn W. (2008). "The Judas of the Gospels and the Gospel of Judas". In Scopello, Madeleine (ed.). The Gospel of Judas in Context: Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Gospel of Judas. Brill. pp. 75–77. ISBN 978-9004167216.

- ↑ McKenzie, John (1966). Dictionary of the Bible. Macmillan Publishing Co. p. 463.

- ↑ The Apochrypha of the Old Testament. Oxford University Press. 1977. p. 106.

- 1 2 Green, Joel B.; McKnight, Scot; Marshall, I. Howard (1992). Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. pp. 406–07. ISBN 978-0-8308-1777-1.

- ↑ (Mark 14:10–11)

- ↑ (Matthew 26:14–16)

- ↑ Luke 22:3–6

- ↑ John 13:27

- ↑ John 12:1–6

- 1 2 Theophylact on Matthew, Chapter 27, 3-5.

- ↑ Luke 4:25–30

- ↑ John 7:28–30

- ↑ John 10:30–39

- ↑ Dimont, Max I. (1962). Jews, God & History (2 ed.). New York City: New American Library. p. 135. ISBN 978-0451146946.

- 1 2 Zwiep 2004.

- ↑ Did Judas betray Jesus Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance, April 2006

- 1 2 "Ancient Manuscript Suggests Jesus Asked Judas to Betray Him". Fox News. New York City: News Corp. Associated Press. 6 April 2006. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013.

- 1 2 Gagné, André (June 2007). "A Critical Note on the Meaning of APOPHASIS in Gospel of Judas 33:1". Laval Théologique et Philosophique. 63 (2): 377–83. doi:10.7202/016791ar.

- ↑ Deconick, April D. (1 December 2007). "Gospel Truth". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ↑ Pitre, Brant (2 February 2016). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7704-3549-3.

- ↑ Laeuchli, Samuel (1953). "Origen's Interpretation of Judas Iscariot". Church History. 22 (4): 253–68. doi:10.2307/3161779. JSTOR 3161779. S2CID 162157799.

- ↑ Feinberg, John S.; Basinger, David (2001). Predestination & free will: four views of divine sovereignty & human freedom. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8254-3489-1.

- ↑ Phillips, John (1986). Exploring the gospel of John: an expository commentary. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-87784-567-6.

- ↑ Chilton, Bruce; Evans, Craig A. (2002). Authenticating the activities of Jesus. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-0391041646. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ↑ Cane, Anthony (2005). The place of Judas Iscariot in Christology. Farnham, England: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0754652847. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ↑ Oropeza, B.J. (2011). In the Footsteps of Judas and Other Defectors: The Gospels, Acts, and Johannine Letters. Vol. 1. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock. pp. 145–50. ISBN 978-1610972895.

- ↑ Robinson, John A.T.; Habermas, Gary R. (1996). "Can We Trust the New Testament?". The Historical Jesus: Ancient Evidence for the Life of Christ. Joplin, Missouri: College Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0899007328.

- ↑ Spong, John Shelby (2010). The Easter Moment. New York City: HarperCollins. p. 150. ISBN 978-0899007328.

- ↑ Susan Gubar, Judas: A Biography (W. W. Norton & Company, 2009) pp. 298–99 (referring to several books, including this one).

- ↑ Mark 14:21

- ↑ John 17:12

- ↑ David L. Jeffrey (1992). A Dictionary of biblical tradition in English literature. W.B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802836342. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ↑ Cornelius Cornelii a Lapide; Thomas Wimberly Mossman The great commentary of Cornelius à Lapide, Matthew 27, London: J. Hodges, 1889–1896.

- ↑ Orchard, O.S.B., Dom Bernard, ed. (1953). A Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture. Thomas Nelson & Sons. p. 901.

- ↑ David L. Jeffrey (1992). A Dictionary of biblical tradition in English literature. W.B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802836342. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ↑ The Encyclopaedia Brittannica (11th ed.). Vol. 15: The Encyclopaedia Brittannica Co. 1911. p. 536.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ The 1560 Geneva Bible (1st ed.). The Bible Museum. 2006.

- ↑ Teachings of the Second Vatican Council. Newman Press. 1966. p. 146.

- ↑ Endres, David (October 2021). "Who's In Hell?". The Catholic Telegraph. 190 (10): 7.

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 1997. pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Malloy, Christopher (2021). False Mercy: Recent Heresies Distorting Catholic Truth. Sophia Institute Press. p. 47.

- ↑ Ott, Ludwig (1954). Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma (2nd ed.). Mercier Press. p. 476.

- ↑ Catechism of the Council of Trent. Translated by Donovan, Rev. J. Lucas Brothers. 1829. p. 213.

- ↑ Catechism of the Council of Trent. Translated by Donovan, Rev. J. Lucas Brothers. 1829. p. 365.

- ↑ Dvornik, Francis (1961). The Ecumenical Councils. Hawthorn Books. p. 91.

- ↑ Aquinas, Thomas (2009). Catena Aurea, vol. II. Preserving Christian Publications. p. 932.

- ↑ Toal, M.F., ed. (1958). Sunday Sermons of the Great Fathers. Vol.2: Henry Regnery Co. p. 183.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Denzinger, Henry (1957). The Sources of Catholic Dogma (30th ed.). B. Herder Book Co. p. 258.

- ↑ Malloy, Christopher (2021). False Mercy: Recent Heresies Distorting Catholic Truth. Sophia Institute Press. p. 41.

- ↑ "extraordinaryform.org/propers/Lent6thThursday-HolyD20.pdf". Extraordinary Form.org. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ↑ Gueranger, O.S.B., Prosper (2021). The Liturgical Year. Vol.6: Passiontide and Holy Week. Preserving Christian Publications. p. 375.

- ↑ Hans Urs von Balthasar (2000) [1990]. Mysterium Paschale. The Mystery of Easter. Translated by Aidan Nichols (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Ignatius Press. p. 77. ISBN 1-68149348-9. 1990 Edition.

- ↑ Power, Dermot (1998). Spiritual Theology of the Priesthood. The Mystery Of Christ And The Mission Of The Priesthood. London: A & C Black. p. 42. ISBN 0-56708595-3.

- ↑ See occurrences on Google Books.

- ↑ Hans Urs von Balthasar (2000) [1990] Preface to the Second Edition.

- ↑ Hans Urs von Balthasar (1988). Theo-Drama. Theological Dramatic Theory, Vol. 5: The Last Act. Translated by Graham Harrison. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-89870185-6.

it must be said that this "kenosis of obedience"...must be based on the eternal kenosis of the Divine Persons one to another.

- ↑ Neuhaus, Richard (2000). Death on a Friday Afternoon. Basic Books. p. 69.

- ↑ Cristiani, Msgr. Leon (1959). Heresies and Heretics. Hawthorn Books. p. 50.

- ↑ Cristiani, Msgr. Leon (1959). Heresies and Heretics. Hawthorn Books. p. 51.

- ↑ "CHURCH FATHERS: The Arabic Gospel of the Infancy of the Saviour". Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ↑ "The Wesley Center Online: The First Gospel of the Infancy of Jesus Christ".

- ↑ John 19:31–37

- ↑ Timeline of early Christianity Archived 8 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine at National Geographic

- ↑ "Judas 'helped Jesus save mankind' Archived 2009-01-07 at the Wayback Machine" BBC News, 7 May 2006 (following National Geographic publication)

- ↑ Cockburn A "The Gospel of Judas Archived 2013-08-10 at the Wayback Machine" National Geographic (USA) May 2006

- ↑ Cockburn A at p. 3 Archived 18 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Deconick A D "Gospel Truth Archived 2017-07-01 at the Wayback Machine" The New York Times 1 December 2007

- ↑ Statement from National Geographic in Response to April DeConick's New York Times Op-Ed "Gospel Truth" Archived 16 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Acocella J. "Betrayal: Should we hate Judas Iscariot? Archived 2009-08-31 at the Wayback Machine" The New Yorker 3 August 2009

- ↑ John Parker (2018) [2007]. The Aesthetics of Antichrist. From Christian Drama to Christopher Marlowe (2nd ed.). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-80146354-9.

- ↑ pelo de Judas Archived 5 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine ("Judas hair") in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española.

- ↑ Page 314 Archived 13 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine of article Red Hair from Bentley's Miscellany, July 1851. The eclectic magazine of foreign literature, science, and art, Volumen 2; Volumen 23, Leavitt, Trow, & Co., 1851.

- 1 2 p. 256 White, Joseph Blanco. Letters from Spain. H. Colburn. ISBN 9781508427162. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) of Letters from Spain, Joseph Blanco White, H. Colburn, 1825. - ↑ Judas colour Archived 13 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine in p. 473 of A glossary: or, Collection of words, phrases, names, and allusions to customs, proverbs, etc., which have been thought to require illustration, in the words of English authors, particularly Shakespeare, and his contemporaries, Volumen 1. Robert Nares, James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps, Thomas Wright. J. R. Smith, 1859

- ↑ Judas' Red Hair and The Jews, Journal of Jewish Art (9), 1982, Melinnkoff R.M

- ↑ Baum, Paull Franklin (1916). "The English Ballad of Judas Iscariot". PMLA. 31 (2): 181–89. doi:10.2307/456954. JSTOR 456954.

- ↑ "NGA – Caravaggio's The Taking of Christ". Archived from the original on 14 January 2015.

- ↑ Baldassare Labanca, Gesù Cristo nella letteratura contemporanea, straniera e italiana, Fratelli Bocca, 1903, p. 240

- ↑ Adams, Byron, ed. (2007), Edward Elgar and His World, Princeton University Press, pp. 140–41, ISBN 978-0-691-13446-8

- ↑ The Magazine of poetry, Volume 2, Issues 1–4 (1890) Charles Wells Moulton, Buffalo, New York "The Magazine of Poetry". 1890. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Equinox – Books – Book Details Archived 15 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Ben Brantley (3 March 2005). "THEATER REVIEW; Judas Gets His Day in Court, but Satan Is on the Witness List". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

General and cited references

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195124743.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2016). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented their Stories of the Savior. New York City: HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-228520-1.

- Gubar, Susan (2009). Judas: A Biography. New York City and London, England: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06483-4.

- Kent, William Henry (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Oropeza, B. J. (2012). In the Footsteps of Judas and Other Defectors: Apostasy in the New Testament Communities, Vol. 1: Gospels, Acts, and Johannine Letters. Eugene: Cascade. ISBN 9781610972895.

- Stanford, Peter (2015). Judas: The Most Hated Name in History. Berkeley, California: Counterpoint. ISBN 978-1-61902-750-3.

- Zwiep, Arie W. (2004). Judas and the Choice of Matthias: A Study on Context and Concern of Acts 1:15–26. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe. Vol. 187. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-148452-0.

External links

- "Judas Iscariot" in the Jewish Encyclopedia

- "Gospel Truth": piece in The New York Times on the Gospel of Judas