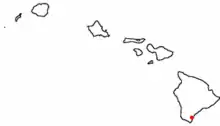

Kamilo Beach (literally, the twisting or swirling currents[1] in Hawaiian), is a beach located on the southeast coast of the island of Hawaii. It is known for its accumulation of plastic marine debris from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.[2]

History

In ancient times, Kamilo Beach was a location where Native Hawaiians would go to find large evergreen logs that drifted ashore from the Pacific Northwest, which they used for building dugout canoes. It was also a location where those who were lost at sea might eventually wash ashore.[3][4]

Description

Kamilo Beach is approximately 1,500 feet (460 m) long, and is located on the remote southeast coast of the Kaʻū District on the island of Hawaii, at coordinates 18°58′13″N 155°35′59″W / 18.97028°N 155.59972°W. There are no paved roads to the beach.

This beach, situated on a lower lava terrace, is a storm beach. It was formed by the deposit of large amounts of sand blown by prevailing winds.[1]

At the point of Kamilo, waves have cut a large indentation, creating a variety of rocky points, ponds, and channels. Most of these are exposed during low tides, and are awash during high tides.

The backshore at Kamilo contains such vegetation as naupaka, milo, and ironwood.[1]

Debris

The beach is an accumulation zone for plastic trash. The debris is forced onto the beach by constant trade winds and converging ocean currents.[5] The debris is situated on the narrow, crescent-shaped strip of white sand, formed along the inland border of this area.[1]

The accumulated garbage that covers Kamilo Beach and an adjacent 2.8 miles (4.5 km) of shoreline consists of 90% plastic.[6] Although some of the items comprising the trash are household products, the vast majority by weight are fishing related such as nets, rope, cones used to trap hagfish, spacers used in oyster farming, buoys, crates, and baskets. Much of the debris is made from plastic pellets, either pre-production nurdles or pellets created from larger plastic items breaking down into smaller pieces.[3]

In 2020, Hawaii's Department of Health designated the beach as impaired based on plastic pollution, which is the first time that any Hawaiian waters will be listed as impaired this way.[7]

Environmental impact

Wildlife in the area has suffered significant damage due to the on- and off-shore garbage. Fishing debris, such as discarded fishing nets and lines, drowns, strangles, and traps birds and marine mammals. Some types of plastic and their constituents, such as bisphenol A, bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, and polystyrene, leach carcinogenic or poisonous chemicals when they break down. Others absorb toxins such as DDT and polychlorinated biphenyls from their surroundings. These toxins are absorbed by animals when consumed.[8]

Cleanup efforts

Multiple community-based cleanup efforts have taken place on Kamilo Beach in recent years. Prior to these efforts, the debris was 8 to 10 feet (2.4 to 3.0 m) high in some places.[4] Most of the efforts to clean up marine debris from Kamilo Beach have been led by the Hawaiʻi Wildlife Fund and their countless beach cleanup volunteers, however other groups, including Imi Pono No Ka 'Aina, Hawaii Rainbow Gatherings, "CITO" geocachers, Sierra Club Hawaii and Beach Environmental Awareness Campaign Hawaiʻi have also helped coordinate occasional events. In 2003, the Hawaiʻi Wildlife Fund organized 100 volunteers and removed over 50 tons (45 metric tonnes) of fishing nets and other marine debris from the beach. [9]

In November 2007, Beach Environmental Awareness Campaign Hawaiʻi volunteers removed more than 4 million pieces of plastic from Kamilo Beach.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Clark, John R. K. (1985), Beaches of the Big Island, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-0976-8 ISBN 0-8248-0976-9, p. 69

- ↑ Sarhangi, Sheila (July 2008). "Getting Trashed". Honolulu Magazine. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- 1 2 Dashefsky, Howard (9 November 2007). "Big Island Beach Attracts Plastic Trash". KHNL NBC 8 Honolulu Hawaii. KHNL. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- 1 2 Weiss, Kenneth R. (2006-08-02). "Plague of Plastic Chokes the Seas". Part 4: Altered Oceans. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2012-12-10. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ↑ Barney, Liz (2020-01-10). "Welcome to Hawaii's 'plastic beach': ground zero of a pollution crisis". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-01-10.

- ↑ "Message in the Waves - Hawai'i". Natural World. BBC Two.

- ↑ Honore, Marcel (July 17, 2020). "EPA Forces State Health Officials To Address Plastic Pollution On Hawaii Beaches". Honolulu Civil Beat. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ↑ McNarie, Alan D. (5 December 2007). "Sea of plastic". Honolulu Weekly. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ↑ Lawrence, Charles (2006). "Hawaii Wildlife Fund - South Point Beach Cleanup 2/06". Photo gallery. PBase.com. Retrieved 2008-12-06. See also: Smith, Dave (2006-02-24). "Try running your toes through this". Hawaii Tribune-Herald.

Further reading

- Handy, Edward Smith Craighill; Elizabeth Green Handy; Mary Kawena Pukui (1972). Native Planters in Old Hawaii: Their Life, Lore, and Environment. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press; Revised edition (1991). ISBN 0-910240-11-6.

External links

- Hawai'i Wildlife Fund

- BBC News video

- Beach Environmental Awareness Campaign Hawai`i

- Algalita research organization - Marine pollutant research documents

- Environmental research study on marine plastic debris

- University of Hawai'i Environmental Center

- Great Garbage Patch site

- Kahea Hawaiian Environmental Alliance

- How the oceans can clean themselves – TED Talk