A keyer is an electronic device used for signaling by hand, by way of pressing one or more switches.[1] The technical term keyer has two very similar meanings, which are nonetheless distinct: One for telegraphy and the other for accessory devices built for computer-human communication:

- For radio-telegraphy, the term "keyer" specifically refers to a device which converts signals from an "iambic" type or "sideswiper" type telegraph key into Morse code for transmission, but excludes the key itself.

- For computer human interface devices, "keyer" generally refers to both a single-hand multi-switch and the electronics which interpret the user key-presses and send the corresponding signals to the computer.

Radiotelegrap keyers

History & telegraphy background

In telegraphy, so-called iambic keys developed out of an earlier generation of novel side-to-side, double-contact keys (called "bushwhackers") and later semi-automatic keys (called "bugs"). Semi-automatic keys were an innovation that had an impulse driven, horizontal pendulum mechanism that (only) created a series of correctly timed "dits". The pendulum would repeatedly tap a switch contact for as long as its control lever was held to the right (or until the impulse from the thumb push was exhausted); telegraphers were obliged to time the "dahs" themselves, by pressing the lever to the left with their knuckle, one press per "dah". When the lever is released, springs push it back to center and break the switch contact (including the resetting the oscillating pendulum, if moving). Because the "dits" are created automatically by the pendulum mechanism, but the "dahs" are keyed the old-fashioned way, the keys are called "semi-automatic". (Modern electronic keyers create both the "dits" and the "dahs" automatically, as long as one of the switches is in contact, and are called "fully-automatic".)

More than just convenience, the keys were needed for medical reasons: Telegraphers would often develop a form of repetitive stress injury, which at that time was called "glass arm" by telegraphers, or "telegrapher's paralysis" in medical literature. It was common and was caused by forcefully "pounding brass" up-and-down on conventional telegraph keys. Keys built for side-to-side motion would not aggravate nor cause the injury, and allowed injured telegraphers to continue in their profession.

Modern telegraphy

With the advent of solid state electronics, the convenience of fully automatic keying became possible by simulating and extending the operation of the old mechanical keys, and special-purpose side-to-side keys were made to operate the electronics, called iambic telegraph keys after the rhythm of telegraphy. In iambic telegraphy the "dot" and the "dash" are separate switches, activated either by one lever or by two separate levers. For as long as the telegrapher holds the lever(s) to the left or right, one of the two telegraph key switches is in contact; the electronics in the keyer will respond by sending a continuous stream of "dits" or "dahs". The operator sends codes by choosing the direction the lever is held, and how long it is held on each side. If the operator swings from side to side slightly erratically, the electronics will none-the-less produce perfectly timed codes.

- The key is the double switch, operated by moving a single or double lever in a sequence of left and right presses, and on a double-lever key, also by pressing both levers at the same time.

- The keyer is the box of electronics that the key is plugged into, which in turn plugs into the socket on the radio which an old-style "straight" key would plug into, which the keyer simulates.

Modern keys with only one lever, which swings horizontally between two contacts and returns to center when released, are called "bushwhackers", or "sideswipers", or "single paddle keys", the same as the old-style double-contact single-lever telegraph keys. The double-lever keys are called "iambic keys", or "double-paddle keys", or "squeeze keys". The name "squeeze key" is because both levers can be pressed at the same time, in which case the electronics then produces a string of "dit-dah-dit-dah-..." (iambic rhythm, hence "iambic key"), or "dah-dit-dah-dit-..." (trochaic rhythm), depending on which side makes contact first. Both types of keys have two distinct contacts, and are wired to the same type plug, and can operate the same electronic keyer (for any commercial keyer made in the last 40 years or so) which itself plugs into the same jack on a radio that one would otherwise directly connect one of the old fashioned telegraph key types to.

Fully automatic electronic keying became popular during the 1960s; at present most Morse code is sent via electronic keyers, although some enthusiasts prefer to use a traditional up-and-down "straight key". Historically appropriate old-fashioned keys are used by naval museums for public demonstrations and for re-enacting civil war events, as well as special radio contests arranged to promote the use of old-style telegraph keys. Because of the popularity of iambic keys, most transmitters introduced into the market within the current century have keyer electronics built-in, so an iambic key plugs directly into a modern transmitter, which also functions as the electronic keyer. (Modern keyer electroncics electrically detect whether the inserted plug belongs to an old type, single-switch key [monophonic plug], or a new type, double-switch key [stereo plug], and responds appropriately for the connected key.)

Analogy of radio teletype keyboards

In a completely automated teleprinter or teletype (RTTY) system, the sender presses keys on a typewriter-style keyboard to send a character data stream to a receiver, and computation alleviates the need for timing to be done by the human operator. In this way, much higher typing speeds are possible. This is an early instance of a multi-key user-input device, as are computer keyboards (which, incidentally, are what one uses for modern RTTY). The keyers discussed below are a smaller, more portable form of user input device.

Computer interface keyers

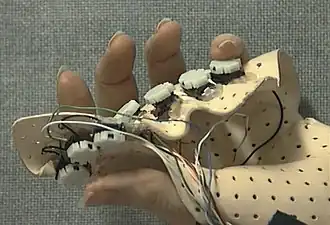

Modern computer interface keyers typically have a large number of switches but not as many as a full-size keyboard; typically between four and fifty.[1] A keyer differs from a keyboard in the sense that it lacks a traditional "board"; the keys are arranged in a cluster[1] which is often held in the hand.

Inspiration from telegraphy

An example of a very simple keyer is a single telegraph key, which used for sending Morse code. In such a use, the term "to key" typically means to turn on and off a carrier wave. For example, it is said that one "keys the transmitter" by interrupting some stage of the amplification of a transmitter with a telegraph key.

When this concept of an iambic telegraph key was introduced to inventor Steve Mann in the 1970s, he mistakenly heard iambic as biambic. He then generalized the nomenclature to include various "polyambic" or "multiambic" keyers, such as a "pentambic" keyer (five keys, one for each finger and the thumb), and "septambic" (four finger and three thumb buttons on a handgrip). These systems were developed primarily for use in early, experimental forms of wearable computing, and have also been adapted to cycling with a heads-up display in projects like BEHEMOTH by Steven K. Roberts. Mann (who primarily works in computational photography) later utilized the concept in a portable backpack-based computer and imaging system, WearCam, which he invented for photographic light vectoring.[2]

Common computer keyer use

Computer interface keyers are typically one-handed grips, often used in conjunction with wearable computers. Unlike keyboards, the wearable keyer has no board upon which the switches are mounted. Additionally, by providing some other function – such as simultaneous grip of flash light and keying – the keyer is effectively hands-free, in the sense that one would still be holding the light source anyway.

Chorded or chording keyboards have also been developed, and are intended to be used while seated having multiple keys mounted to a board rather than a portable grip. One type of these, the so-called half-QWERTY layout, uses only minimal chording, requiring the space bar to be pressed down if the alternate hand is used. It is otherwise a standard QWERTY keyboard of full size. It, and many other innovations in keyboard controls, were designed to deal with hand disabilities in particular.

References

- 1 2 3 Mann, S. (2002) [2001]. "Appendix B: Multiambic keyer for use while engaged in other activities". Intelligent Image Processing. John Wiley – via wearcam.org.

- ↑ "[no title cited]".

External links

- "Keyers". Tech. eyetap.org. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. — summary of keyers, commercially made keyers, other links, etc.

- "GKOS back-panel chording keyboard". gkos.com. — an open standard for handheld devices

- "Twiddler 2". handykey.com. — one-handed chording keyboard/mouse

- "Data Egg". xaphoon.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2006. — one-handed chording keyboard for handheld devices

- "Yet another one-hand keyboard". chordite.com. — Do-it-yourself, wearable, one-hand keyboard prototypes

- "Wearable keyer suitable for QRP use". electronicsusa.com. — leg mount accessory

- "Intelligent Image Processing". wearcam.org (online textbook). — See Appendix on keyers

- "How to make your own custom-molded perfect-fit keyer". wearcam.org.

- "Spiff chorder". vassar.edu. Archived from the original on 2009-03-17. Retrieved 2009-06-12. — keyer for daily wearable computer use