Khawr al Udayd

خور العديد | |

|---|---|

Sand dunes at Khawr al Udayd, photographed in 2004. | |

Khawr al Udayd | |

| Coordinates: 24°37′48″N 51°17′46″E / 24.630°N 51.296°E | |

| Country | |

| Municipality | Al Wakrah Municipality |

| Area | |

| • Total | 705 km2 (272 sq mi) |

| Population (2015) | |

| • Total | 7 |

| • Density | 0.0099/km2 (0.026/sq mi) |

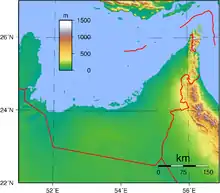

Khawr al Udayd, (Arabic: خور العديد; also spelled Khor al Adaid and Khor al-‘Udeid) is a settlement and inlet of the Persian Gulf located in Al Wakrah Municipality in southeast Qatar, on the border with Saudi Arabia. It is known to local English speakers as the "Inland Sea". In the past it accommodated a small town and served as the center of a long-running territorial dispute between Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani and Sheikh Zayed bin Khalifa Al Nahyan. At the present, it is a major tourist destination for Qatar.

The area was declared a nature reserve in 2007.[1] Qatar has pitched Khawr al Udayd's potential inclusion as a World Heritage Site to UNESCO but it currently only occupies the Tentative List.[2]

History

Settlement and subsequent conflicts

The area of Khawr al Udayd had been a point of friction between Qatar and what is now Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).[3] Khawr al Udayd had served as a refuge for pirates from the Emirate of Abu Dhabi (now part of the UAE) during the 19th century. Members of the Bani Yas tribe migrated and settled in the area on three separate occasions: 1835, 1849 and 1869. According to a historical overview of Khawr al Udayd written by the British government in India, "in 1836, Al-Kubaisat, a section of the Bani-Yas, under Sheikh Khadim-bin-Nahman, being desirous of avoiding the consequences of certain recent piracies, seceded from Abu Dhabi and established themselves at Odeid. [...] In 1849, there was a fresh secession, followed by a second compulsory return; at length, in 1869, a party under Sheikh Buttye-bin-Khadim again settled at Odeid, and repudiated their allegiance to the parent State."[4]

Perhaps the most notable among the settlers in 1835 was the pirate Jasim bin Jabir, who was joined there by his crew. The residents of eastern Qatar abetted the pirates of Khawr al Udayd in their pillaging of vessels off the coast of Abu Dhabi, resulting in a British naval force being sent to the settlement in 1836 to accost the piratical acts. The British ordered the chiefs of major Qatari towns to immediately desist from sending supplies to the pirates and instructed them to seize the pirate's boats.[5] Additionally, the British naval force set fire to one of the pirate's vessels. As a result, Jassim bin Jabir relocated to Doha in September 1836.[6]

After receiving approval from the British in May 1837, the Sheikh of Abu Dhabi, wishing to punish the seceders, sent his troops to sack the settlement at Khawr al Udayd; 50 of its inhabitants were killed and its houses and fortifications were dismantled during the event.[7] The British claim that "the leniency and moderation with which he [the Sheikh] used his victory induced the seceders to return to Abu Dhabi".[4]

In 1869, the Bani Yas tribe once again seceded from Abu Dhabi to resettle in Khawr al Udayd under Sheikh Buttye-bin-Khadim.[4] According to a description offered of Khawr al Udayd sometime after this migration, the colony was inhabited by approximately 200 Bani Yas tribespeople who owned a total 30 pearling ships. The area was well protected, containing a small fort with two towers in the center of the town.[8]

Ottoman control

The Qatari Peninsula fell under Ottoman control in late 1871 after Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani, recognized as ruler of the peninsula, acquiesced control in exchange for protection from the Sheikhs of Bahrain and Abu Dhabi and agreed to fly the Ottoman flag at his palace. In January 1872, Qatar was formally incorporated into the Ottoman Empire as a province in Najd with Sheikh Jassim being appointed its kaymakam (sub-governor).[9] According to a British memorandum written in 1879 by Adolphus Warburton Moore, "in August 1873 they [the Ottomans] were reported by the Acting Resident in the Persian Gulf to have established an influence over all the Guttur coast as far as the Odeid boundaries".[10]

For his part, Buttye-bin-Khadim, sheikh of the Bani Yas at Khawr al Udayd, not only absolutely refused to submit to Abu Dhabi, but stated that his people were in their own right at Odeid, and independent of both Qatar and the Ottomans. The territorial limits of the colony were declared to extend from Ras-al-Hala, midway to Wakrah in Qatar, continuously along the southern coast through Odeid to a point abreast of the island of Sir Bani Yas. He further claimed the island of Dalma and other islets within that circuit. He asserted that this territory constituted the ancient home of the Al-Kubaisat. He then admitted he had been offered the Turkish flag by Sheikh Jassim, but had refused it, saying he was under British protection.[11] Communications between British officials reveal that rumors persisted that Sheikh Buttye-bin-Khadim flew the Ottoman flag on Fridays.[12] These rumors were later found to be true, with future communiques confirming the occasional hoisting of the Ottoman flag in Khawr al Udayd.[13]

In June 1873, Sheikh Zayed bin Khalifa Al Nahyan of Abu Dhabi wrote to the British Political Resident in the Persian Gulf requesting permission to launch a naval invasion of Khawr al Udayd, but was rejected by the British government.[12] Once again he requested permission in November 1874, but was told that the British government could not permit such a proceeding. He claimed to have recently received letters from Ottoman local officials claiming that Khawr al Udayd was under their protection.[14]

Piracy incidents

Shortly after the peninsula fell under Ottoman control, the British government reprimanded the Ottomans on numerous occasions for failing to prevent piratical acts from being carried out off Khawr Al Udayd's coast. Adolphus Warburton Moore's memo states, "During the summer of 1876 there was a marked increase of piratical acts along the Guttur coast." Select instances are given:[15]

- "In the month of August a rumour reached the Officiating Resident, to the effect that another party of the Beni Hajir had seized a boat belonging to the Oman pearl divers at Odeid."

- "In the same month the Chief of Aboothabee complained that two of his boats, which had anchored in the Bay of Odeid, had been attacked from the shore, one man being wounded, and one killed."

- "Again in August a section of the Beni Hajir, residing at Odeid, under the rule of Sheikh Salim bin Shafee, embarked from that port, and made an attack upon a boat belonging to Guttur, from which property to the value of

400 was plundered."

400 was plundered."

The British memo also mentions the 1869 defection of the Bani Yas tribe from the Sheikh of Abu Dhabi and subsequent resettlement of Khawr al Udayd. Discussing the Sheikh's response to their defection, the memo states:

In regard to these dissidents Colonel Prideaux wrote (16th September 1876): "The Chief of Aboothabee, though naturally incensed at the defection of his tribesmen, has throughout behaved with praiseworthy moderation and forbearance; and although by frequent appeals to this Residency he continues to assert his claims upon Odeid, he has never attempted to enforce them by any act which might be deemed inconsistent with his treaty obligations." I do not doubt that if the question at issue were simply between the Chief of Aboothabee and his refractory tribesmen, it might be satisfactorily arranged without any great difficulty but it is to some degree complicated by the fact that the Chief of Odeid is in possession of a Turkish flag which he occasionally hoists, and under the protection of which it is believed that he would voluntarily place himself if any attempt were made to coerce him.[13]

In addition to hoisting the Ottoman flag (alongside the Trucial flag), it was discovered that the Sheikh of Khawr al Udayd had been paying an annual tribute of 40 to 50 dollars to the Ottomans through Sheikh Jassim around 1877.[14] Although Khawr al Udayd had likely been under Ottoman protection for two to three years by that point, aside from the small contingent of Ottoman officials who came to settle terms, there was no Ottoman presence in the village to speak of.[16] This absence was mainly attributed to the area's limited potable water availability.[17]

British response to piracy

The British, after having conducted an investigation into these so-called piratical acts, concluded that the culprits were not the Bani Hajer, but the Al Murrah tribe; and that the Sheikh of Khawr al Udayd had not been implicated, but that "he was too weak to prevent his ports being made use of". Colonel Prideaux, who was the acting Persian Gulf Resident in Edward Charles Ross' absence, suggested that the British should facilitate a reconciliation between the Bani Yas in Khawr al Udayd and the Sheikh of Abu Dhabi so that the area, including its territorial waters, would fall under the umbrella of British protection. He claimed that, should this prove unsuccessful, the British government would do well to provide assistance to the Sheikh of Abu Dhabi in exercising his authority over the land, by force if necessary. In such an event, he predicted that the Ottomans would not intervene.

After much deliberation, the British Government concurred with Colonel Prideaux's view and empowered the Resident to use his best endeavors to promote a reunion between the colonists at Khawr al Udayd and the main body of the Bani Yas tribe of Abu Dhabi, and further authorized him "to afford assistance, if necessary, to the Trucial Chief of Abuthabi in coercing the seceders."[16] The British Government established the following facts regarding the piracy:[18]

- That the acts of piracy complained of were committed by members of the Al Murrah tribe, a tribe nominally dependent on the Ottoman Government.

- That the pirates proceeded on their expedition from ports belonging to the Chief of Khawr al Udayd.

- That the Chief of Khawr al Udayd in no way countenanced or assisted the use of his ports as a starting place for piratical expeditions.

- That the reason why the Chief of Khawr al Udayd was too weak to prevent the piracy was due to his and his follower's secession from the Bani Yas tribe inhabiting Abu Dhabi.

- That the reason why the Chief of Abu Dhabi has not yet invaded Khawr al Udayd is, that he has been prevented from so doing by the British Government.

Accompanying these findings were two directives issued by the British Government:

- That endeavours be made to induce the Ottoman Government to take measures to restrain the piratical proceedings of the Al Murrah tribe; and

- That measures be taken by the Royal Navy to prevent the ports of Khawr al Udayd from being used as a rendezvous for pirates.

The British Government also instructed their liaison to the Ottomans, the British Ambassador in Constantinople Austen Henry Layard, to relay to the Ottoman Government the need to send forces to the weaker Sheikhs in Qatar so that they may subvert piracy in their ports, but the liaison was advised that no reference of Khawr al Udayd should be made, "because it was doubtful whether the Turkish Government exercised any substantial authority over the Chief of that place, and it was inexpedient to provoke a discussion on the point." In June 1877, yet another act of piracy was committed by ships belonging to Khawr al Udayd upon sailors from Al Wakrah, several of whom were captured.[19] Following the incident, Colonel Prideaux wrote to Sheikh Buttye-bin-Khadim of Khawr al Udayd warning him to accept reunification with the Bani Yas of Abu Dhabi, otherwise "other steps will be taken", while also writing to Sheikh Zayed of Abu Dhabi to reassure him of British support for his efforts to preside over the settlement at Khawr al Udayd.[20]

In the aftermath of the piracy in June, Sheikh Buttye-bin-Khadim, while admitting his men forcibly captured sailors from Al Wakrah, did not comply with British demands to release the prisoners.[20] Thus, in October 1877, Colonel Prideaux recommended sending warships to Khawr al Udayd as punishment for violating the Perpetual Maritime Truce, unless its inhabitants submit to the Sheikh of Abu Dhabi's rule.[21] Edward Charles Ross informed the British Government in December that attempts at reconciliation between Sheikh Zayed and Sheikh Buttye-bin-Khadim were met without success.[21]

Invasion and destruction

In 1878, it was reported that the British Government and the Sheikh of Abu Dhabi had concocted a plan to invade Khawr al Udayd, supposedly to curtail the piracy of its inhabitants. In response, Sheikh Jassim threatened to occupy Khawr al Udayd, as he had perceived the proposed military excursion to be in violation of Qatar's territorial integrity.[8] Climatically, a massive invasion of Khawr al Udayd was launched by the Sheikh of Abu Dhabi in concert with the British in 1879. Recounting the incident, British records state that:

Sir A. Layard [Austen Henry Layard], writing on the 28th May, reported that Sadık Pasha, the Ottoman Minister for Foreign Affairs, had read to him a telegram from the Wali of Basra, complaining that Zaid-bin-Khalifa, with 70 boats and accompanied by an English war steamer and the British Consul at Bushire, had attacked Odeid, which he described as a dependency of the Turkish district of Catar (El-Katr). The inhabitants having fled, the village was pillaged and destroyed, and all the boats carried off. The Porte hoped that some explanation would be afforded of this descent upon Turkish territory. Lord Cranbrook, to whom the papers were referred, declined to give any detailed expression of opinion until he had consulted the Government of India; but in the meantime he drew the attention of the Foreign Office to the correspondence of 1877, in which the India Office recommended that a discussion with the Porte in regard to the status of Odeid should, if possible, be avoided.[22]

In 1881, Sheikh Jassim once again announced to the Political Resident his intention to occupy Khawr al Udayd in order to re-inhabit it and to defend Qatar from pirates and naval invasions. After being reminded that the territory was under the protection of the British, he rescinded his plans.[23] On 31 August 1886, it was reported that Sheikh Jassim and several of his followers departed Doha to settle Khawr al Udayd. He was warned against his plan by a British official, and the Royal Navy dispatched a vessel to prevent him from advancing. Eventually, he returned to Doha without establishing a settlement in Khawr al Udayd.[24]

In April 1889, Sheikh Jassim sent a letter to the Wali of Basra in which he reported that Sheikh Zayed was preparing to invade Qatar and pleaded for support, claiming that Sheikh's Zayed's forces numbered close to 20,000 troops while he could barely muster 4,000 troops. Although the Wali believed that Sheikh Jassim was inflating figures for his own gain, he instructed Akif Pasha, Mutasarrıf of Najd Sanjak, to take preventative measures in Qatar by reinforcing Khawr al Udayd with 500 men. Before the troops were dispatched, Akif Pasha was summoned to Basra in August 1888 to discuss administrative reforms in Bahrain and Qatar with the Wali. During the meeting, Akif Pasha recommended appointing a mudir to Khawr al Udayd with a salary of 750 kurushes and a gendarmerie force.[25] He claimed that this, along with other steps taken by the Porte, would result in the establishment of a thriving village in Khawr al Udayd which could potentially generate large amounts of tax revenue. Furthermore, he stated, such measures would help repel foreign incursions.[26] However, the prime underlying motive behind these reforms were to reduce British influence in the Persian Gulf. After these decisions were written into a bill by the Council of Ministers, Sultan Abdul Hamid II, having received the bill on 13 January 1890, signed it into effect on 2 February 1890.[27]

Resettlement attempts by the Ottomans and Sheikh Jassim

By 1890 news had broken about the newly commissioned project by the Ottomans to rebuild Khawr al Udayd. The British grew concerned over this prospect because an Ottoman settlement in what they considered territory of Abu Dhabi would be exceedingly difficult to disperse through diplomatic means. In British political circles, rumors were circulating in January 1891 that the Ottomans had installed mudirs (governors) in Khawr al Udayd and north-bound Zubarah, and that 400 Ottoman troops were en route to garrison the towns.[28] These rumors are confirmed by declassified communications between the Wali of Basra and the Office of the Grand Vizier exchanged in mid-January.[29]

In February 1891, it was learnt by the British that Sheikh Jassim, under the aegis of the Ottomans, had returned to his plans of occupying Khawr al Udayd.[28] He reportedly asked around 40 members of the Kubaisat tribe living in Al Wakrah to settle in Khawr al Udayd in an attempt to rebuild the village.[30] The tribe replied that they were willing to adhere to this proposal, provided that one of Jassim's sons serves as their Sheikh, as most of the tribe members refused to live under an Ottoman governor. At the same time, Sheikh Jassim was under pressure by the Ottomans to agree to their proposals to install administrative officials at Khawr al Udayd and Zubarah and to establish a customs house at Al Bidda. While he was not overtly concerned about the first proposal as he had not yet found willing participants to resettle these two places, he vehemently opposed the establishment of an Ottoman customs house in Qatar. All prospects of resettling Khawr al Udayd were abandoned when Sheikh Jassim, unsatisfied with the increasing usurpation of control by the Ottomans, resigned as kaymakam of Qatar in August 1892. This culminated in the Battle of Al Wajbah in March 1893 in which Sheikh Jassim's forces defeated the Ottomans troops stationed in Doha, resulting in a downsizing of Ottoman presence in the peninsula.[30]

Resettlement proposal by Sheikh Zayed

Sheikh Zayed of Abu Dhabi and Lieutenant-Colonel C. A. Kemball, Officiating Political Resident in the Persian Gulf, held a meeting in October 1903 in which they discussed the rebuilding and resettlement of Khawr al Udayd. In January 1904, the Assistant Political Agent in Bahrain received a letter from Sheikh Zayed regarding the same topic:

The rebuilding of Odeid will have a detrimental effect on Al Bidda and Wakra, from which places it will draw some of their residents. Odeid possesses one of the most secure harbours for native craft on this side of the Persian Gulf . It will become a centre for the pearl trade in that region much to the disadvantage of Al Bidda which now has a large share of the trade on account of its proximity to the central pearl banks. A new market will be opened for our enterprising British Indians who would probably share in the Katr pearl trade which is now exclusively in the hands of Sheikh Ahmed bin Thani and his nephews. The port is situated about thirty miles nearer to Bahrein than to Abu Dhabi for sailing vessels, so that possibly it will draw some of its supplies from Bahrein. And finally it will put an effectual stop to Turkish pretensions to it. The extra responsibility devolving upon His Majesty’s Government by the venture may be described as nominal only. After the severe check received by the Turks in their attempt on Bahrein in 1895 they will hardly lay themselves open again to any similar demoralizing rebuff by instigating the Katr Arabs to attack Odeid by sea and should they be so ill-advised as to do so, the Arabs of that region are not likely to listen to them after what they experienced on the occasion referred to. The only other danger is that it may be open to attack from the land side by raiding Bedouins. The nearest water-supply accessible to an hostile party is in the vicinity of Wajba about fifty miles away, so that an attempt would be attended with serious risks, the contingency is therefore remote in the extreme.[31]

Sheikh Zayed wrote to the Political Resident, also in 1904, asking for permission to reoccupy Khawr al Udayd. He received a negative response from the British, according to a communique written by Assistant Secretary to the Government of India R.E. Holland which stated "that while the Government of India are prepared to prevent the place being occupied by anyone other than himself, they are not disposed under present conditions to assist him in reoccupying it."[32]

Ottoman administrative reforms

More than thirty years after the Ottomans established a protectorate in the Qatari Peninsula, they designated four administrative districts (nehiye) on the peninsula in December 1902, with Khawr al Udayd (simply referred to as Adide by the Porte)[33] being among them. Ottoman sources allege that this was in response to British disturbance of the nomadic tribespeople in Qatar by installing numerous poles in the peninsula, including five in Zubarah and Khawr al Udayd.[34] The British officially protested and refused to recognize Ottoman jurisdiction over the peninsula, especially over Khawr al Udayd. They demanded that the Ottomans not station administrative officials in these districts, to which the Ottomans promised they would comply. However, by early 1903, the Ottomans had already appointed the first mudir – Yusuf Effendi in Al Wakrah.[35]

Abdülkarim Vefik Efendi (known to British intelligence as Agha Abdul Karim bin Agha Hasan), a former tax official in Qatif, was the mudir-designate for Khawr al Udayd.[34] In March 1903, British sources indicated that the mudir-designate was reassigned elsewhere. According to Lieutenant-Colonel C. A. Kemball, Abdülkarim Efendi requested a reassignment from the Mutasarrıf of al-Hasa after being made aware of the desolateness of Khawr al Udayd. Abdülkarim Efendi stated, according to Kemball, that a mudir of Kurdish origins had been assigned in his place and was awaiting orders in Basra.[36] Amidst heavy pressure from the British to rescind their assignment of government officials in Qatar, the Porte abolished all its mudir posts on the peninsula in 1904.[35]

It was reported that in August 1910, the Ottomans had again assigned a mudir in the peninsula, this time to the Khawr al Udayd district. British intelligence identified the mudir as Sulaiman Effendi.[37] A British government official deemed this move "a determination to assert and extend Ottoman sovereignty over the neighbourhood of El Katr" and was instructed to hand in a written protest pointing out that "El Odeid is in the territory of one of the Trucial Chiefs who are under the protection of His Majesty’s Government”.[35] Nonetheless, when HMS Redbreast was sent to inspect Khawr al Udayd later that year, it found no evidence of an Ottoman mudir.[38]

Later Ottoman period

A brief description of Khawr al Udayd is given in 1910 by W. Graham Greene:

Information about this locality is very meagre. Anchorage is reported to exist in from six to ten fathoms close to the shore of the northern entrance point of Khor al Odeid, which is described as a winding inlet five miles in length opening out into a lagoon about five miles long and three miles wide. Landing from boats would probably be easy on the shore of the inlet and lagoon, the depths of which vary considerably."[39]

J. G. Lorimer's comprehensive Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, published in 1908 and 1915 as a handbook for British political agents, offers a more complete account of Khawr al Udayd:

In English formerly known as "Khore Alladeid." An inlet or creek on the coast of the Abu Dhabi Principality at its extreme western end: it lies about 180 miles, almost due west, from the town of Abu Dhabi. The boundary of Qatar is either at, or a short distance to the north of, the inlet. [...] There are now no permanent inhabitants at 'Odaid, and it is not visited by Bedouins from the interior; but fishermen from Abu Dhabi spend some months here in winter, and fine mullet are caught by them. A village occupied by seceders from Abu Dhabi; of the Qubaisat section of the Bani Yas, has existed at Odaid at various times. The village was situated on the south side of the creek at a short distance from the entrance and consisted of about 100 houses: the inhabitants lived by fishing and obtained their drinking water from 4 wells which were less than a mile from the place and contained brackish water at 2 fathoms below the surface; they had no dates or cultivation. Prior to 1866 the defenses of this village consisted of a fort with two towers, of 7 other detached towers, and of blockhouses protecting the wells. The settlement was finally abandoned in 1880.[40]

Later 20th century

Throughout the 20th century, Khawr al Udayd was the focus of border disputes between Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The UAE Emirate of Abu Dhabi desired to have a border with Qatar here, but it was agreed in 1974 that Khawr al Udayd should border Saudi Arabia instead.[3] However, that did not stop the issue from continuing into the 21st century, with the UAE and Saudi Arabia holding another discussion regarding Khawr al Udayd and their borders in 2005.[41][42]

21st century

In November 2021, Saudi Arabia and Qatar demarcated the Qatar–Saudi Arabia border and Qatar was given access to the entirety of Khawr al Udayd. Qatar's border with Saudi Arabia has been moved further south, expanding the peninsula's geographical boundaries.[43]

Geography

The khor (inlet) at Khawr al Udayd consists of a winding channel, 6 miles long, which runs inland in a south-westerly direction; within it opens out into a lagoon 6 miles long from north-north-east to south-south-west and 3 miles broad. The lagoon contains soundings of as much as 6 fathoms; but ordinary vessels on account of reefs, cannot approach within 3 miles of the entrance of the khor. A ridge of stony hills, 300 feet high on the south side of the entrance, is called Jabal Al 'Odaid; and on the north side of the creek, overlooking it, are sand hills known as Niqa Al Maharaf.[40] Niqa Al Maharaf forms the southern extremity of a narrow range of high white sand hills skirting the coast known as Naqiyan, with the northern extremity going by the name Naqiyan Abu Qasbatain.[44]

In a 2010 survey of Khawr al Udayd's coastal waters conducted by the Qatar Statistics Authority, it was found that its average depth was 4 meters (13 ft) and its average pH was 7.93. Furthermore, the waters had a salinity of 57.09 psu, an average temperature of 26.13 °C (79 °F) and 6.02 mg/L of dissolved oxygen.[45]

Nature reserve

The UNESCO-recognized Khawr al Udayd Reserve is Qatar's largest nature reserve.[46] Also known by its English name Inland Sea, the area was declared a nature reserve in 2007 and occupies an area of approximately 1,833 km2 (708 sq. mi.).[1] Historically, the area was used for camel grazing by nomads, and is still used for the same purpose to a lesser extent. Various flora and fauna are supported in its ecosystem, such as ospreys, dugongs and turtles. Most notable is the reserve's unique geographic features. The appearance and the quick formation of its sabkhas is distinct from any other system of sabkhas, as is the continuous infilling of its lagoon.[2]

Tourism

Khawr al Udayd's beach is a popular tourist attraction in Qatar.[47] The most common routes to the beach are via Mazrat Turaina and Mesaieed.[48]

Demographics

As of the 2010 census, the settlement comprised 14 housing units[49] and 4 establishments.[50] There were 42 people living in the settlement, of which 100% were male and 0% were female. Out of the 42 inhabitants, 100% were 20 years of age or older and 0% were under the age of 20. The literacy rate stood at 64.3%.[51]

Employed persons made up 100% of the total population. Males accounted for 100% of the working population.[51]

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 2010[52] | 42 |

| 2015[53] | 7 |

References

- 1 2 "Khor Al Adaid Reserve". Qatar eNature. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Khor Al-Adaid natural reserve". UNESCO. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- 1 2 "Arabian Boundary Disputes - Cambridge Archive Editions". Archiveeditions.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 "'TURKISH JURISDICTION IN THE ISLANDS AND WATERS OF THE PERSIAN GULF, AND ON THE ARAB LITTORAL' [108v] (2/28)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [797] (952/1782)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [798] (953/1782)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "'Extracts from Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman and Central Arabia by J G Lorimer CIE, Indian Civil Service' [46v] (97/180)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- 1 2 Moorehead, John (1977). In Defiance of The Elements: A Personal View of Qatar. Quartet Books. p. 54. ISBN 9780704321496.

- ↑ Rahman, Habibur (2006). The Emergence Of Qatar. Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 978-0710312136.

- ↑ "'Persian Gulf - Turkish jurisdiction along the Arabian coast (Part II)' [148r] (3/45)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'TURKISH JURISDICTION IN THE ISLANDS AND WATERS OF THE PERSIAN GULF, AND ON THE ARAB LITTORAL' [109v] (4/28)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- 1 2 "'TURKISH JURISDICTION IN THE ISLANDS AND WATERS OF THE PERSIAN GULF, AND ON THE ARAB LITTORAL' [110r] (5/28)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- 1 2 "'Persian Gulf - Turkish jurisdiction along the Arabian coast (Part II)' [153r] (13/45)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- 1 2 "'TURKISH JURISDICTION IN THE ISLANDS AND WATERS OF THE PERSIAN GULF, AND ON THE ARAB LITTORAL' [111v] (8/28)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'Persian Gulf - Turkish jurisdiction along the Arabian coast (Part II)' [152r] (11/45)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- 1 2 "'TURKISH JURISDICTION IN THE ISLANDS AND WATERS OF THE PERSIAN GULF, AND ON THE ARAB LITTORAL' [112r] (9/28)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'Persian Gulf gazetteer. Part 1. Historical and political materials. Précis of Katar [Qatar] affairs, 1873-1904.' [10v] (20/92)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'TURKISH JURISDICTION IN THE ISLANDS AND WATERS OF THE PERSIAN GULF, AND ON THE ARAB LITTORAL' [112v] (10/28)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'TURKISH JURISDICTION IN THE ISLANDS AND WATERS OF THE PERSIAN GULF, AND ON THE ARAB LITTORAL' [113r] (11/28)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- 1 2 "'TURKISH JURISDICTION IN THE ISLANDS AND WATERS OF THE PERSIAN GULF, AND ON THE ARAB LITTORAL' [113v] (12/28)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- 1 2 "'TURKISH JURISDICTION IN THE ISLANDS AND WATERS OF THE PERSIAN GULF, AND ON THE ARAB LITTORAL' [114r] (13/28)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'TURKISH JURISDICTION IN THE ISLANDS AND WATERS OF THE PERSIAN GULF, AND ON THE ARAB LITTORAL' [108r] (1/28)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'Persian Gulf gazetteer. Part 1. Historical and political materials. Précis of Katar [Qatar] affairs, 1873-1904.' [17v] (34/92)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'Persian Gulf gazetteer. Part 1. Historical and political materials. Précis of Katar [Qatar] affairs, 1873-1904.' [20r] (39/92)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Zekeriya Kurşun (30 June 2010). The Ottomans in Qatar: A History of Anglo-Ottoman Conflicts in the Persian Gulf. Vol. Analecta Isisiana: Ottoman and Turkish Studies - Book 11. Istanbul: Gorgias PR. p. 84. ISBN 978-1617191107.

- ↑ Zekeriya Kurşun (30 June 2010). The Ottomans in Qatar: A History of Anglo-Ottoman Conflicts in the Persian Gulf. Vol. Analecta Isisiana: Ottoman and Turkish Studies - Book 11. Istanbul: Gorgias PR. p. 85. ISBN 978-1617191107.

- ↑ Zekeriya Kurşun (30 June 2010). The Ottomans in Qatar: A History of Anglo-Ottoman Conflicts in the Persian Gulf. Vol. Analecta Isisiana: Ottoman and Turkish Studies - Book 11. Istanbul: Gorgias PR. p. 86. ISBN 978-1617191107.

- 1 2 "'Persian Gulf gazetteer. Part 1. Historical and political materials. Précis of Katar [Qatar] affairs, 1873-1904.' [24r] (47/92)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Zekeriya Kurşun (30 June 2010). The Ottomans in Qatar: A History of Anglo-Ottoman Conflicts in the Persian Gulf. Vol. Analecta Isisiana: Ottoman and Turkish Studies - Book 11. Istanbul: Gorgias PR. p. 87. ISBN 978-1617191107.

- 1 2 "'Persian Gulf gazetteer. Part 1. Historical and political materials. Précis of Katar [Qatar] affairs, 1873-1904.' [24v] (48/92)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "File 160/1903 'Persian Gulf: El Katr; appointment of Turkish Mudirs; question of Protectorate Treaty with El Katr' [116v] (237/860)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "File 160/1903 'Persian Gulf: El Katr; appointment of Turkish Mudirs; question of Protectorate Treaty with El Katr' [79r] (162/860)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "File 160/1903 'Persian Gulf: El Katr; appointment of Turkish Mudirs; question of Protectorate Treaty with El Katr' [384r] (772/860)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- 1 2 Zekeriya Kurşun (30 June 2010). The Ottomans in Qatar: A History of Anglo-Ottoman Conflicts in the Persian Gulf. Vol. Analecta Isisiana: Ottoman and Turkish Studies - Book 11. Istanbul: Gorgias PR. p. 107. ISBN 978-1617191107.

- 1 2 3 "File 160/1903 'Persian Gulf: El Katr; appointment of Turkish Mudirs; question of Protectorate Treaty with El Katr' [9v] (23/860)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 10 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "File 160/1903 'Persian Gulf: El Katr; appointment of Turkish Mudirs; question of Protectorate Treaty with El Katr' [166r] (336/860)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "'File: E/4. Turkish mudirs of Wakra and Zubara on the Qatar Peninsular' [95v] (221/234)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "File 757/1909 'Persian Gulf:- Turkey and Turkish aggression (Occupation of Zakhnuniyeh Island. Attitude in piracy cases. Mudirs at Zubara, Odaid and Wakra) British Relations with Turkey in Persian Gulf' [59v] (123/495)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 10 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "File 160/1903 'Persian Gulf: El Katr; appointment of Turkish Mudirs; question of Protectorate Treaty with El Katr' [45r] (94/860)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- 1 2 "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol. II. Geographical and Statistical. J G Lorimer. 1908' [1367] (1478/2084)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Saudi Arabia confirms discussing border disputes with UAE". Archived from the original on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ↑ "Border disputes erupt between Saudi Arabia, UAE; Riyadh denies". Archived from the original on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ↑ Ibrahim, Menatalla (4 November 2021). "Qatar completes border demarcation with Saudi Arabia". Doha News. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ↑ "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol. II. Geographical and Statistical. J G Lorimer. 1908' [1509] (1624/2084)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Qatar Infrastructure Statistics" (PDF). Qatar Statistics Authority. May 2012. p. 29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ Anisha Bijukumar (15 April 2017). "Approx 23 per cent of Qatar area is nature reserve". The Peninsula. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ↑ "Tourism". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "Khor Al Udeid beach: Joy with caution". The Peninsula Qatar. 5 July 2010. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "Housing units, by type of unit and zone (April 2010)" (PDF). Qatar Statistics Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ↑ "Establishments by status of establishment and zone (April 2010)" (PDF). Qatar Statistics Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Geo Statistics Application". Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ↑ "2010 population census" (PDF). Qatar Statistics Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "2015 Population census" (PDF). Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. April 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2017.