| Part of a series on |

| Epistemology |

|---|

| This is a subseries on philosophy. In order to explore related topics, please visit navigation. |

Knowledge is an awareness of facts, a familiarity with individuals and situations, or a practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often characterized as true belief that is distinct from opinion or guesswork by virtue of justification. While there is wide agreement among philosophers that propositional knowledge is a form of true belief, many controversies focus on justification. This includes questions like how to understand justification, whether it is needed at all, and whether something else besides it is needed. These controversies intensified in the latter half of the 20th century due to a series of thought experiments that provoked alternative definitions.

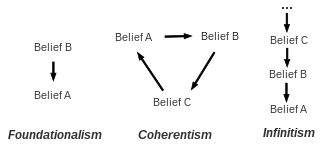

Knowledge can be produced in many ways. The main source of empirical knowledge is perception, which involves the usage of the senses to learn about the external world. Introspection allows people to learn about their internal mental states and processes. Other sources of knowledge include memory, rational intuition, inference, and testimony. According to foundationalism, some of these sources are basic in that they can justify beliefs, without depending on other mental states. This claim is rejected by coherentists, who contend that a sufficient degree of coherence among all the mental states of the believer is necessary for knowledge. According to infinitism, an infinite chain of beliefs is needed.

The main discipline investigating knowledge is epistemology. It studies what people know, how they come to know it, and what it means to know something. It discusses the value of knowledge and the thesis of philosophical skepticism, which questions the possibility of knowledge. Knowledge is relevant to many fields. Science tries to acquire it using the scientific method, which is based on repeatable experimentation, observation, and measurement. Various religions hold that humans should seek knowledge and that God or the divine is the source of knowledge. The anthropology of knowledge studies how knowledge is acquired, stored, retrieved, and communicated in different cultures. The sociology of knowledge examines under what sociohistorical circumstances knowledge arises, and what sociological consequences it has. The history of knowledge investigates how knowledge in different fields has developed, and evolved, in the course of history.

Definitions

Knowledge is a form of familiarity, awareness, understanding, or acquaintance. It often involves the possession of information learned through experience.[1] There is wide, though not universal, agreement among philosophers that knowledge involves a cognitive success or an epistemic contact with reality, like making a discovery.[2] Many academic definitions of knowledge focus on propositional knowledge or knowledge of facts, as in "I know that Dave is at home", and understand it as a form of true belief.[3] Other types of knowledge include knowledge-how in the form of practical competence, as in "she knows how to swim", and "knowledge by acquaintance" as a form a familiarity with the known object based on previous direct experience.[4]

Despite agreements about the general characteristics of knowledge, its exact definition is disputed. Some disagreements arise from the goal that a proposed definition is supposed to fulfill. One approach is to focus on the most salient features of knowledge with the goal of giving a practically useful definition.[5] Another is to try to provide a theoretically precise definition by listing the conditions that are individually necessary and jointly sufficient. The terms "analysis of knowledge" and "conceptions of knowledge" are often used for this approach.[6] It can be understood in analogy to how chemists analyze a sample by seeking a list of all the chemical elements composing it.[7] According to a different view, knowledge is a unique state that cannot be analyzed in terms of other phenomena.[8]

Other disagreements are caused by methodological differences, for example, whether scholars base their inquiry on abstract and general intuitions (known as methodism) or concrete and specific cases (known as particularism).[9] Another source of dispute is the role of ordinary language in one's inquiry: the weight given to how the term "knowledge" is used in everyday discourse.[10] According to Ludwig Wittgenstein, for example, there is no clear-cut definition of knowledge since it is just a cluster of concepts related through family resemblance.[11] Different conceptions of the standards of knowledge are also responsible for disagreements. Some epistemologists, like René Descartes, hold that knowledge demands very high requirements, like absolute certainty or infallibility. According to this view, knowledge is very rare. Others see knowledge as a rather common phenomenon, prevalent in many everyday situations, without excessively high standards.[12]

Knowledge is often understood as a state of an individual person but it can also refer to a characteristic of a group of people as group knowledge, social knowledge, or collective knowledge.[13] The term may further denote knowledge stored in documents, as in "knowledge housed in the library"[14] or the knowledge base of an expert system.[15] Knowledge is closely related to intelligence, with one difference being that intelligence is more about the ability to acquire, process, and apply information, while knowledge concerns information and skills that a person already possesses.[16] Knowledge is often contrasted with ignorance, which is linked to a lack of understanding, education, and true beliefs.[17]

The word knowledge has its roots in the 12th-century Old English word cnawan, which comes from the Old High German word gecnawan.[18] The English word includes various meanings that some other languages distinguish using several words. For example, Latin uses the words cognitio and scientia for "knowledge" while French uses the words connaitre and savoir for "to know".[19] In ancient Greek, four important terms for knowledge were used: epistēmē (unchanging theoretical knowledge), technē (expert technical knowledge), mētis (strategic knowledge), and gnōsis (personal intellectual knowledge).[20]

The main discipline studying knowledge is called epistemology or theory of knowledge. It examines the nature of knowledge and justification, how knowledge arises, and what value it has. Further topics include the different types of knowledge and the limits of what can be known.[21] Some social sciences are interested in knowledge as a social phenomenon and tend to understand it as a wide human phenomenon similar to culture.[22]

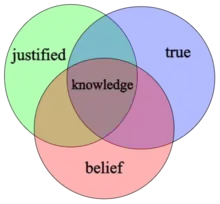

Justified true belief

An often-discussed definition characterizes knowledge as justified true belief (JTB). This definition identifies three essential features: it is (1) a belief that is (2) true and (3) justified.[23][lower-alpha 1] Truth is a widely accepted feature of knowledge. It implies that, while it may be possible to believe something false, one cannot know something false.[25] That knowledge is a form of belief implies that one cannot know something if one does not believe it. Some everyday expression seem to violate this principle, like the claim that "I do not believe it, I know it!". But the point of such expressions is usually empasize one's confidence rather than denying that a belief is involved.[26]

The main controversy surrounding the JTB definition concerns its third feature: justification.[27] This component is often included because of the impression that some true beliefs are not forms of knowledge. Specifically, this covers cases of superstition, lucky guesses, or erroneous reasoning. For example, a person who is convinced that a coin flip will land heads usually does not know that even if their belief turns out to be true. This indicates that there is more to knowledge than just being right about something.[28]

The JTB definition solves this problem by identifying proper justification as the additional component needed. This approach is able to explain why superstition or lucky guesses may be true but do not amount to knowledge.[29] Many philosophers understand justification internalistically (internalism): a belief is justified if it is supported by another mental state of the person, such as a sensory experience, a memory, or a second belief. This mental state has to constitute a sufficiently strong evidence or reason for the believed claim. Some modern versions modify the JTB definition by using an externalist conception of justification instead. This means that justification depends not only on factors internal to the believer's mind but also on external factors. According to reliabilist theories of justification, a belief is justified if it is produced by a reliable process, like sensory perception or logical reasoning. According to causal theories, justification requires that the believed fact causes the belief. This is the case, for example, when a bird sits on a tree and a person forms a belief about this fact because they see the bird.[30]

Gettier problem and alternatives

The JTB definition came under severe criticism in the 20th century, when Edmund Gettier formulated a series of counterexamples.[31] They purport to present concrete cases of justified true beliefs that fail to constitute knowledge. The reason for their failure is usually a form of epistemic luck: the beliefs are justified but their justification is not relevant to the truth.[32] In a well-known example, there is a country road with many barn facades and only one real barn. The person driving is not aware of this, stops in front of the real barn by a lucky coincidence, and forms the justified true belief that he is in front of a barn. It has been argued that the person does not know that they are in front of a real barn since they would not have been able to tell the difference.[33] This means that it is a lucky coincidence that this justified belief is also true.[34]

The responses to this and other counterexamples have been diverse. According to some, they show that the JTB definition of knowledge is deeply flawed and that a radical reconceptualization of knowledge is necessary, often by denying justification a role.[35] This can happen, for example, by replacing the justification condition with reliability or by seeing knowledge as the manifestation of cognitive virtues. Another approach is to define knowledge in regard to the function it plays in cognitive processes as that which provides reasons for thinking or doing something.[36] Responses on the other hand of the spectrum hold that Gettier cases pose no serious problems and no radical reconceptualization is required. They usually focus on minimal modifications of the JTB definition, for example, by making small adjustments to how justification is defined.[37]

Responses between these two camps acknowledge that Gettier cases pose a problem and suggest a moderate departure from the JTB definition. They agree with the JTB definition that justified true belief is a necessary condition of knowledge. However, they disagree that it is a sufficient condition. They hold instead that an additional criterion, some feature X, is necessary for knowledge. For this reason, they are often referred to as JTB+X definitions of knowledge.[38] A closely related approach speaks not of justification but of warrant and defines warrant as justification together with whatever else is necessary to arrive at knowledge.[39]

Many candidates for the fourth feature have been suggested. In this regard, knowledge may be defined as justified true belief that does not depend on any false beliefs, that there are no defeaters[lower-alpha 2] present, or that the person would not have the belief if it was false.[41] Such and similar definitions are successful at avoiding many of the original Gettier cases. However, they are often undermined by newly conceived counterexamples.[42] To avoid all possible cases, it may be necessary to find a criterion that excludes all forms of epistemic luck. It has been argued that such a criterion would set the standards of knowledge very high by requiring that the belief be infallible to succeed in all cases.[43] This would mean that very few beliefs amount to knowledge, if any.[44] For example, Richard Kirkham suggests that our definition of knowledge requires that the evidence for the belief necessitates its truth.[45] There is still very little consensus in the academic discourse as to which of the proposed modifications or reconceptualizations is correct and there are various alternative definitions of knowledge.[46]

Types

A common distinction among types of knowledge is between propositional knowledge, or knowledge-that, and non-propositional knowledge in the form of practical skills or acquaintance.[47] Other distinctions focus on how the knowledge is acquired and on the content of the known information.[48]

Propositional

Propositional knowledge, also referred to as declarative and descriptive knowledge, is a form of theoretical knowledge about facts, like knowing that "2 + 2 = 4". It is the paradigmatic type of knowledge in analytic philosophy.[49] Propositional knowledge is propositional in the sense that it involves a relation to a proposition. Since propositions are often expressed through that-clauses, it is also referred to as knowledge-that, as in "Akari knows that kangaroos hop".[50] In this case, Akari stands in the relation of knowing to the proposition "kangaroos hop". Closely related types of knowledge are know-wh, for example, knowing who is coming to dinner and knowing why they are coming.[51] These expressions are normally understood as types of propositional knowledge since they can be paraphrased using a that-clause.[52]

Propositional knowledge takes the form of mental representations involving concepts, ideas, theories, and general rules. These representations connect the knower to certain parts of reality by showing what they are like. They are often context-independent, meaning that they are not restricted to a specific use or purpose.[53] Propositional knowledge encompasses both knowledge of specific facts, like that the atomic mass of gold is 196.97 u, and general laws, like that the color of leaves of some trees changes in autumn.[54] Because of the dependence on mental representations, it is often held that the capacity for propositional knowledge is exclusive to relatively sophisticated creatures, such as humans. This is based on the claim that advanced intellectual capacities are needed to believe a proposition that expresses what the world is like.[55]

Non-propositional

Non-propositional knowledge is knowledge in which no essential relation to a proposition is involved. The two most well-known forms are knowledge-how (know-how or procedural knowledge) and knowledge by acquaintance.[56] To possess knowledge-how mean to have some form of practical ability, skill, or competence.[57] Examples include knowing how to ride a bicycle or knowing how to swim. Some of the abilities responsible for knowledge-how involve forms of knowledge-that, as in knowing how to prove a mathematical theorem, but this is not generally the case.[58] Some types of knowledge-how do not require a highly developed mind, in contrast to propositional knowledge. In this regard, knowledge-how is more common in the animal kingdom. For example, an ant knows how to walk even though it presumably lacks a mind sufficiently developed to represent the corresponding proposition.[55]

Knowledge by acquaintance is familiarity with something that results from direct experiential contact.[59] The object of knowledge can be a person, a thing, or a place. For example, by eating chocolate, one gets knowledge by acquaintance of chocolate and visiting Lake Taupō leads to the formation of knowledge of acquaintance of Lake Taupō. In these cases, the person forms non-inferential knowledge based on first-hand experience without necessarily acquiring factual information about the object. By contrast, it is also possible to indirectly learn a lot of propositional knowledge about chocolate or Lake Taupō by reading books without having the direct experiential contact required for knowledge by acquaintance.[60] Knowledge by acquaintance plays a central role in Bertrand Russell's epistemology. He holds that it is more basic than propositional knowledge since to understand a proposition, one has to be acquainted with its constituents, like the universals and particular objects it refers to.[61]

A priori and a posteriori

The distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge depends on the role of experience in the processes of formation and justification.[62] To know something a posteriori means to know it on the basis of experience.[63] For example, by seeing that it rains outside or hearing that the baby is crying, one acquires a posteriori knowledge of these facts.[64] A priori knowledge is possible without any experience to justify or support the known proposition.[65] Mathematical knowledge, such as that 2 + 2 = 4, belongs to a priori knowledge since no empirical investigation is necessary to confirm this fact. In this regard, a posteriori knowledge is empirical knowledge while a priori knowledge is non-empirical knowledge.[66]

The relevant experience in question is primarily identified with sensory experience. However, some non-sensory experiences, like memory and introspection, are often included as well. But some conscious phenomena are excluded in this context. For example, the conscious phenomenon of a rational insight into the solution of a mathematical problem does not make the resulting knowledge a posteriori.[67] The same is the case for the experience needed to understand the claim in which the term is expressed. For example, knowing that "all bachelors are unmarried" is a priori knowledge because no sensory experience is necessary to confirm this fact even though experience was needed to learn the meanings of the terms "bachelor" and "unmarried".[68]

One difficulty for a priori knowledge is to explain how it is possible. It is usually seen as unproblematic that one can come to know things through experience but it is not clear how knowledge is possible without experience. One of the earliest solutions to this problem is due to Plato, who argues that the soul already possesses the knowledge and just needs to recollect or remember it to access it again.[69] A similar explanation is given by René Descartes, who holds that a priori knowledge exists as innate knowledge present in the mind of each human.[70] A further approach is to posit a special mental faculty responsible for this type of knowledge, often referred to as rational intuition or rational insight.[71]

Others

Various other types of knowledge are discussed in the academic literature. In philosophy, "self-knowledge" refers to a person's knowledge of their own sensations, thoughts, beliefs, and other mental states. A common view is that self-knowledge is more direct than knowledge of the external world, which relies on the interpretation of sense data. Because of this, it is traditionally claimed that self-knowledge is indubitable, like the claim that a person cannot be wrong about whether they are in pain. However, this position is not universally accepted in the contemporary discourse and an alternative view states that self-knowledge also depends on interpretations that could be false.[72] In a slightly different sense, self-knowledge can also refer to knowledge of the self as a persisting entity with certain personality traits, preferences, physical attributes, relationships, goals, and social identities.[73]

Metaknowledge is knowledge about knowledge. It can arise in the form of self-knowledge but includes other types as well, such as knowing what someone else knows or what information is contained in a scientific article. Other aspects of metaknowledge include knowing how knowledge can be acquired, stored, distributed, and used.[74]

Common knowledge is knowledge that is publicly known and shared by most individuals within a community. It establishes a common ground for communication, understanding, social cohesion, and cooperation.[75] General knowledge encompasses common knowledge but also includes knowledge that many people have been exposed to at some point but may not be able to immediately recall.[76] Common knowledge contrasts with specialized knowledge, which is only possessed by a few experts and belongs to a specific domain. It is also referred to as domain knowledge.[77]

Situated knowledge is knowledge specific to a particular situation.[78] It is closely related to practical or tacit knowledge, which is learned and applied in specific circumstances. This especially concerns certain forms of acquiring knowledge, such as trial and error or learning from experience.[79] In this regard, situated knowledge usually lacks a more explicit structure and is not articulated in terms of universal ideas.[80] The term is often used in feminism and postmodernism to argue that many forms of knowledge are not absolute but depend on the concrete historical, cultural, and linguistic context.[78]

Explicit knowledge is knowledge that can be fully articulated, shared, and explained. Examples are the knowledge of historical dates and mathematical formulas. It can be acquired through traditional learning methods, such as reading books and attending lectures. It contrasts with tacit knowledge, which is not easily articulated or explained to others. Examples are the ability to recognize someone's face and the practical expertise of a master craftsman. Tacit knowledge is often learned through first-hand experience or direct practice.[81] In some cases, it is possible to convert tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge into one another.[82]

Knowledge can be occurrent or dispositional. Occurrent knowledge is knowledge that is actively involved in cognitive processes. Dispositional knowledge, by contrast, lies dormant in the back of a person's mind and is given by the mere ability to access the relevant information. For example, if a person knows that cats have whiskers then this knowledge is dispositional most of the time and becomes occurrent while they are thinking about it.[83]

Many forms of Eastern spirituality and religion distinguish between higher and lower knowledge. They are also referred to as para vidya and apara vidya in Hinduism or the two truths doctrine in Buddhism. Lower knowledge is based on the senses and the intellect. It encompasses both mundane or conventional truths as well as discoveries of the empirical sciences.[84] Higher knowledge is understood as knowledge of God, the absolute, the true self, or the ultimate reality. It belongs neither to the external world of physical objects nor to the internal world of the experience of emotions and concepts. Many spiritual teachings stress the importance of higher knowledge to progress on the spiritual path and to see reality as it truly is beyond the veil of appearances.[85]

Sources

Sources of knowledge are ways how people come to know things. They can be understood as cognitive capacities that are exercised when a person acquires new knowledge.[86] Various sources of knowledge are discussed in the academic literature, often in terms of the mental faculties responsible. They include perception, introspection, memory, inference, and testimony. However, not everyone agrees that all of them actually lead to knowledge. Usually, perception or observation, i.e. using one of the senses, is identified as the most important source of empirical knowledge.[87] Knowing that a baby is sleeping is observational knowledge if it was caused by a perception of the snoring baby. However, this would not be the case if one learned about this fact through a telephone conversation with one's spouse. Direct realists explain observational knowledge by holding that perception is a direct contact with the perceived object. Indirect realists contend that this contact happens indirectly: people can only directly perceive sense data, which are then interpreted as representing external objects. This contrast affects whether the knowledge of external objects is direct or indirect and may thus have an impact on how certain perceptual knowledge is.[88]

Introspection is often seen in analogy to perception as a source of knowledge, not of external physical objects, but of internal mental states. A traditionally common view is that introspection has a special epistemic status by being infallible. According to this position, it is not possible to be mistaken about introspective facts, like whether one is in pain, because there is no difference between appearance and reality. However, this claim has been contested in the contemporary discourse. Critics argue that it may be possible, for example, to mistake an unpleasant itch for a pain or to confuse the experience of a slight ellipse for the experience of a circle.[89] Perceptual and introspective knowledge often act as a form of fundamental or basic knowledge. According to some empiricists, they are the only sources of basic knowledge and provide the foundation for all other knowledge.[90]

Memory differs from perception and introspection in that it is not as independent or basic as they are since it depends on other previous experiences.[91] The faculty of memory retains knowledge acquired in the past and makes it accessible in the present, as when remembering a past event or a friend's phone number.[92] It is generally seen as a reliable source of knowledge. However, it can be deceptive at times nonetheless, either because the original experience was unreliable or because the memory degraded and does not accurately represent the original experience anymore.[93]

Knowledge based on perception, introspection, and memory may give rise to inferential knowledge, which comes about when reasoning is applied to draw inferences from other known facts.[94] For example, the perceptual knowledge of a Czech stamp on a postcard may give rise to the inferential knowledge that one's friend is visiting the Czech Republic. This type of knowledge depends on other sources of knowledge responsible for the premises. Rationalists argue that some forms of knowledge arise from reason alone completely independent of observation and introspection. They use this approach to explain how a priori beliefs, like the mathematical belief that 2 + 2 = 4, constitute knowledge. One explanation of knowledge by pure reason holds that there is a mental faculty of rational intuition. This faculty can be used to explain why such general and abstract beliefs amount to knowledge even though there seem to be no sensory perceptions that could justify them.[95] However, difficulties in providing a clear account of pure reason or rational intuition have led some empirically minded epistemologists to doubt that they constitute independent sources of knowledge.[96] A closely related approach is to hold that this type of knowledge is innate. According to Plato's theory of recollection, for example, it is accessed through a special form of remembering.[97]

Testimony is often included as an additional source of knowledge. Unlike the other sources, it is not tied to one specific cognitive faculty. Instead, it is based on the idea that one person can come to know a fact because another person talks about this fact. Testimony can happen in numerous ways, like regular speech, a letter, a newspaper, or an online blog. The problem of testimony consists in clarifying why and under what circumstances testimony can lead to knowledge. A common response is that it depends on the reliability of the person pronouncing the testimony: only testimony from reliable sources can lead to knowledge.[98]

Structure

The structure of knowledge is the way in which the mental states of a person need to be related to each other for knowledge to arise.[99] A common view is that a person has to have good reasons for holding a belief if this belief is to amount to knowledge. When the belief is challenged, the person may justify it by referring to their reason for holding it. In many cases, this reason depends itself on another belief that may as well be challenged. An example is a person who believes that Ford cars are cheaper than BMWs. When their belief is challenged, they may justify it by claiming that they heard it from a reliable source. This justification depends on the assumption that their source is reliable, which may itself be challenged. The same may apply to any subsequent reason they cite.[100] This threatens to lead to an infinite regress since the epistemic status at each step depends on the epistemic status of the previous step.[101] Theories of the structure of knowledge offer responses for how to solve this problem.[100]

The three most common theories are foundationalism, coherentism, and infinitism. Foundationalists and coherentists deny the existence of an infinite regress, in contrast to infinitists.[100] According to foundationalists, some basic reasons have their epistemic status independent of other reasons and thereby constitute the endpoint of the regress.[102] Some foundationalists hold that certain sources of knowledge, like perception, provide basic reasons. Another view is that this role is played by certain self-evident truths, like the knowledge of one's own existence and the content of one's ideas.[103] The view that basic reasons exist is not universally accepted. One criticism states that there should be a reason why some reasons are basic while others are not. According to this view, the putative basic reasons are not actually basic since their status would depend on other reasons. Epistemologists that agree about the existence of basic reasons may disagree about which reasons constitute basic reasons.[104]

Coherentists and infinitists avoid these problems by denying the contrast between basic and non-basic reasons. Coherentists argue that there is only a finite number of reasons, which mutually support and justify one another. This is based on the intuition that beliefs do not exist in isolation but form a complex web of interconnected ideas that is justified by its coherence rather than by a few privileged foundational beliefs.[105] One difficulty for this view is how to demonstrate that it does not involve the fallacy of circular reasoning.[106] If two beliefs mutually support each other then a person has a reason for accepting one belief if they already have the other. However, the mutual support alone is not a good reason for newly accepting both beliefs at once. A closely related issue is that there can be distinct sets of coherent beliefs. Coherentists face the problem of explaining why someone should accept one coherent set rather than another.[105] For infinitists, in contrast to foundationalists and coherentists, there is an infinite number of reasons. This view embraces the idea that there is a regress since each reason depends on another reason. One difficulty for this view is that the human mind is limited and may not be able to possess an infinite amount of reasons. This raises the question whether, according to infinitism, human knowledge is possible at all.[107]

Value

Knowledge may be valuable either because it is useful or because it is good in itself. Knowledge can be useful by helping a person achieve their goals. For example, if one knows the answers to questions in an exam one is able to pass that exam or by knowing which horse is the fastest, one can earn money from bets. In these cases, knowledge has instrumental value.[108] However, not all forms of knowledge are useful and many beliefs about trivial matters have no instrumental value. This concerns, for example, knowing how many grains of sand are on a specific beach or memorizing phone numbers one never intends to call. In a few cases, knowledge may even have a negative value. For example, if a person's life depends on gathering the courage to jump over a ravine, then having a true belief about the involved dangers may hinder them from doing so.[109]

Besides having instrumental value, knowledge may also have intrinsic value. This means that some forms of knowledge are good in themselves even if they do not provide any practical benefits. According to Duncan Pritchard, this applies to forms of knowledge linked to wisdom.[110] The value of knowledge is relevant to the field of education, specifically to the issue of choosing which knowledge should be passed on to the student.[111]

A more specific issue in epistemology concerns the question of whether or why knowledge is more valuable than mere true belief.[112] There is wide agreement that knowledge is usually good in some sense but the thesis that knowledge is better than true belief is controversial. An early discussion of this problem is found in Plato's Meno in relation to the claim that both knowledge and true belief can successfully guide action and, therefore, have apparently the same value. For example, it seems that mere true belief is as effective as knowledge when trying to find the way to Larissa.[113] According to Plato, knowledge is better because it is more stable.[114] Another suggestion is that knowledge gets its additional value from justification. One difficulty for this view is that while justification makes it more probable that a belief is true, it is not clear what additional value it provides in comparison to an unjustified belief that is already true.[115]

The problem of the value of knowledge is often discussed in relation to reliabilism and virtue epistemology.[116] Reliabilism can be defined as the thesis that knowledge is reliably formed true belief. This view has difficulties in explaining why knowledge is valuable or how a reliable belief-forming process adds additional value.[117] According to an analogy by Linda Zagzebski, a cup of coffee made by a reliable coffee machine has the same value as an equally good cup of coffee made by an unreliable coffee machine.[118] This difficulty in solving the value problem is sometimes used as an argument against reliabilism.[119] Virtue epistemology, by contrast, offers a unique solution to the value problem. Virtue epistemologists see knowledge as the manifestation of cognitive virtues. They argue that knowledge has additional value due to its association with virtue. This is based on the idea that cognitive success in the form of the manifestation of virtues is inherently valuable independent of whether the resulting states are instrumentally useful.[120]

Philosophical skepticism

Philosophical skepticism in its strongest form, also referred to as radical skepticism, is the thesis that humans lack any form of knowledge or that knowledge is impossible. Very few philosophers have explicitly defended this position. It has been influential nonetheless, usually in a negative sense: many scholars see it as a serious challenge to any epistemological theory and often try to show how their preferred theory overcomes it.[121] A weaker form of philosophical skepticism advocates the suspension of judgment as a form of attaining tranquility while remaining humble and open-minded.[122]

One argument for radical skepticism is the dream argument. According to it, perceptual experience is not a source of knowledge since dreaming provides unreliable information and a person could be dreaming without knowing it. Because of this inability to discriminate between dream and perception, it is argued that there is no perceptual knowledge of the external world.[123] A similar often-cited thought experiment assumes that a person is not a regular human being but a brain in a vat that receives electrical stimuli. These stimuli give the brain the false impression of having a body and interacting with the external world. The basic argument is the same: since the person is unable to tell the difference, they do not know that they have a body responsible for reliable perceptions.[124] Both these thought experiments focus on the problem of underdetermination. This problem arises in cases where the available evidence is not sufficient to make a rational decision between competing theories. In such cases, a person is not justified in believing one theory rather than the other. If this is always the case then a global skepticism follows.[124] Another skeptical argument assumes that knowledge requires absolute certainty and aims to show that all human cognition is fallible and fails to meet this standard.[125]

An influential argument against radical skepticism states that radical skepticism is self-contradictory. The argument is based on the idea that denying the existence of knowledge is itself a knowledge-claim.[126] Another response comes from common sense philosophy. It states that many of the ordinary beliefs denied by radical skepticism are more reliable than the abstract reasoning cited in favor of skepticism. According to this view, the conclusion is not that ordinary beliefs fail to amount to knowledge but that there must be some kind of flaw in the reasoning process leading to radical skepticism.[127] Pragmatist epistemologists tend to reject the claim by some radical skeptics that knowledge requires infalliblity and argue instead that all beliefs and theories are fallible hypotheses that may need to be revised as new evidence is acquired.[128]

Less global forms of skepticism deny that knowledge exists within a specific area or discipline, sometimes referred to as local or selective skepticism.[129] They are often motivated by the idea that certain phenomena do not accurately represent their subject matter and may lead to false impressions. Some skeptics accept that people can know about their own sensory impressions and experiences but not about the external world. This is based on the idea that beliefs about the external world are mediated through the senses, which can be misleading at times. This problem does not affect the sensory impressions themselves but the inferences drawn from them. In this regard, a person cannot know that there is a red Ferrari in the street but they can know that they have the sensory impression of the color red.[130] Other forms of local skepticism accept scientific knowledge but deny the possibility of moral or religious knowledge, for example, because there is no reliable way to empirically measure whether a moral claim is true or false.[131]

In various disciplines

Science

The scientific approach is usually regarded as an exemplary process of how to gain knowledge about empirical facts.[132] Scientific knowledge includes mundane knowledge about easily observable facts, for example, chemical knowledge that certain reactants become hot when mixed together. It also encompasses knowledge of less tangible issues, like claims about the behavior of genes, neutrinos, and black holes.[133]

A key aspect of most forms of science is that they seek natural laws that explain empirical observations.[132] Scientific knowledge is discovered and tested using the scientific method. This method aims to arrive at reliable knowledge by formulating the problem in a clear way and by ensuring that the evidence used to support or refute a specific theory is public, reliable, and replicable. This way, other researchers can repeat the experiments and observations in the initial study to confirm or disconfirm it.[134] The scientific method is often analyzed as a series of steps. According to some formulations, it begins with regular observation and data collection. Based on these insights, scientists then try to find a hypothesis that explains the observations. The hypothesis is then tested using a controlled experiment to compare whether predictions based on the hypothesis match the observed results. As a last step, the results are interpreted and a conclusion is reached whether and to what degree the findings confirm or disconfirm the hypothesis.[135]

The progress of scientific knowledge is traditionally seen as a gradual and continuous process in which the existing body of knowledge is increased at each step. This view has been challenged by some philosophers of science, such as Thomas Kuhn, who holds that between phases of incremental progress, there are so-called scientific revolutions in which a paradigm shift occurs. According to this view, some basic assumptions are changed due to the paradigm shift. This results in a radically new perspective on the body of scientific knowledge that is incommensurable with the previous outlook.[136]

History

The history of knowledge is the field of inquiry that studies how knowledge in different fields has developed and evolved in the course of history. It is closely related to the history of science but covers a wider area that includes knowledge from fields like philosophy, mathematics, education, literature, art, and religion. It further covers practical knowledge of specific crafts, medicine, and everyday practices. It investigates not only how knowledge is created and employed but also how it is disseminated and preserved.[137]

Before the ancient period, knowledge about social conduct and survival skills was passed down orally and in the form of customs from one generation to the next.[138] The ancient period saw the rise of major civilizations starting about 3000 BCE in Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and China. The invention of writing in this period significantly increased the amount of stable knowledge within society since it could be stored and shared without being limited by imperfect human memory.[139] During this time, the first developments in scientific fields like mathematics, astronomy, and medicine were made. They were later formalized and greatly expanded by the ancient Greeks starting in the 6th century BCE. Other ancient advancements concerned knowledge in the fields of agriculture, law, and politics.[140]

In the medieval period, religious knowledge was a central concern and religious institutions, like the catholic church in Europe, influenced intellectual activity.[141] Jewish communities set up yeshivas as centers for studying religious texts and Jewish law.[142] In the Islamic world, madrasa schools were established and focused on Islamic law and Islamic philosophy.[143] Many of the intellectual achievements of the ancient period were preserved, refined, and expanded during the Islamic Golden Age from the 8th to 13th centuries.[144] Centers of higher learning were established in this period in various regions, like Al-Qarawiyyin University in Morocco,[145] the Al-Azhar University in Egypt,[146] the House of Wisdom in Iraq,[147] and the first universities in Europe,[148] This period also saw the formation of guilds, which preserved and advanced technical and craft knowledge.[149]

In the Renaissance period, starting in the 14th century, there was a renewed interest in the humanities and sciences.[150] The printing press was invented in the 15th century and significantly increased the availability of written media and the general literacy of the population.[151] These developments served as the foundation of the scientific revolution in the Age of Enlightenment starting in the 16th and 17th centuries. It led to an explosion of knowledge in fields such as physics, chemistry, biology, and the social sciences.[152] The technological advancements that accompanied this development made possible the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries.[153] In the 20th century, the development of computers and the Internet led to a vast expansion of knowledge by revolutionizing how knowledge is stored, shared, and created.[154]

Religion

Knowledge plays a central role in many religions. Knowledge claims about the existence of God or religious doctrines about how each one should live their lives are found in almost every culture.[155] However, such knowledge claims are often controversial and are commonly rejected by religious skeptics and atheists.[156] The epistemology of religion is the field of inquiry studying whether belief in God and in other religious doctrines is rational and amounts to knowledge.[157] One important view in this field is evidentialism. It states that belief in religious doctrines is justified if it is supported by sufficient evidence. Suggested examples of evidence for religious doctrines include religious experiences such as direct contact with the divine or inner testimony as when hearing God's voice.[158] Evidentialists often reject that belief in religious doctrines amounts to knowledge based on the claim that there is not sufficient evidence.[159] A famous saying in this regard is due to Bertrand Russell. When asked how he would justify his lack of belief in God when facing his judgment after death, he replied "Not enough evidence, God! Not enough evidence."[160]

However, religious teachings about the existence and nature of God are not always seen as knowledge claims by their defenders. Some explicitly state that the proper attitude towards such doctrines is not knowledge but faith. This is often combined with the assumption that these doctrines are true but cannot be fully understood by reason or verified through rational inquiry. For this reason, it is claimed that one should accept them even though they do not amount to knowledge.[156] Such a view is reflected in a famous saying by Immanuel Kant where he claims that he "had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith."[161]

Distinct religions often differ from each other concerning the doctrines they proclaim as well as their understanding of the role of knowledge in religious practice.[162] In both the Jewish and the Christian traditions, knowledge plays a role in the fall of man in which Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden. Responsible for this fall was that they ignored God's command and ate from the tree of knowledge, which gave them the knowledge of good and evil. This is seen as a rebellion against God since this knowledge belongs to God and it is not for humans to decide what is right or wrong.[163] In the Christian literature, knowledge is seen as one of the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit.[164] In Islam, "the Knowing" (al-ʿAlīm) is one of the 99 names reflecting distinct attributes of God. The Qur'an asserts that knowledge comes from God and the acquisition of knowledge is encouraged in the teachings of Muhammad.[165]

In Buddhism, knowledge that leads to liberation is called vijjā. It contrasts with avijjā or ignorance, which is understood as the root of all suffering. This is often explained in relation to the claim that humans suffer because they crave things that are impermanent. The ignorance of the impermanent nature of things is seen as the factor responsible for this craving.[166] The central goal of Buddhist practice is to stop suffering. This aim is to be achieved by understanding and practicing the teaching known as the Four Noble Truths and thereby overcoming ignorance.[167] Knowledge plays a key role in the classical path of Hinduism known as jñāna yoga or "path of knowledge". Its aim is to achieve oneness with the divine by fostering an understanding of the self and its relation to Brahman or ultimate reality.[168]

Anthropology

The anthropology of knowledge is a multi-disciplinary field of inquiry.[169] It studies how knowledge is acquired, stored, retrieved, and communicated.[170] Special interest is given to how knowledge is reproduced and undergoes changes in relation to social and cultural circumstances.[171] In this context, the term knowledge is used in a very broad sense, roughly equivalent to terms like understanding and culture.[172] This means that the forms and reproduction of understanding are studied irrespective of their truth value. In epistemology, on the other hand, knowledge is usually restricted to forms of true belief. The main focus in anthropology is on empirical observations of how people ascribe truth values to meaning contents, like when affirming an assertion, even if these contents are false.[171] This also includes practical components: knowledge is what is employed when interpreting and acting on the world and involves diverse phenomena, such as feelings, embodied skills, information, and concepts. It is used to understand and anticipate events to prepare and react accordingly.[173]

The reproduction of knowledge and its changes often happen through some form of communication used to transfer knowledge.[174] This includes face-to-face discussions and online communications as well as seminars and rituals. An important role in this context falls to institutions, like university departments or scientific journals in the academic context.[171] Anthropologists of knowledge understand traditions as knowledge that has been reproduced within a society or geographic region over several generations. They are interested in how this reproduction is affected by external influences. For example, societies tend to interpret knowledge claims found in other societies and incorporate them in a modified form.[175]

Within a society, people belonging to the same social group usually understand things and organize knowledge in similar ways to one another. In this regard, social identities play a significant role: people who associate themselves with similar identities, like age-influenced, professional, religious, and ethnic identities, tend to embody similar forms of knowledge. Such identities concern both how a person sees themselves, for example, in terms of the ideals they pursue, as well as how other people see them, such as the expectations they have toward the person.[176]

Sociology

The sociology of knowledge is the subfield of sociology that studies how thought and society are related to each other.[177] Like the anthropology of knowledge, it understands "knowledge" in a wide sense that encompasses philosophical and political ideas, religious and ideological doctrines, and folklore, law, and technology. The sociology of knowledge studies in what sociohistorical circumstances knowledge arises, what consequences it has, and on what existential conditions it depends. The examined conditions include physical, demographic, economic, and sociocultural factors. An example of a theory in this field is due to Karl Marx, who claims that the dominant ideology in a society is a product of and changes with the underlying socioeconomic conditions.[177] Another example is found in forms of decolonial scholarship that claim that colonial powers are responsible for the hegemony of Western knowledge systems. They seek a decolonization of knowledge to undermine this hegemony.[178]

Others

Formal epistemology studies knowledge using formal tools found in mathematics and logic.[179] An important issue in this field concerns the epistemic principles of knowledge. These are rules governing how knowledge and related states behave and in what relations they stand to each other. The transparency principle, also referred to as the luminosity of knowledge, states that knowing something implies the second-order knowledge that one knows it. This principle implies that if Heike knows that today is Monday, then she also knows that she knows that today is Monday.[180] According to the conjunction principle, if a person has justified beliefs in two separate propositions then they are also justified in believing the conjunction of these two propositions. In this regard, if Bob has a justified belief that dogs are animals and another justified belief that cats are animals, then he is justified to believe the conjunction of these two propositions, i.e. that both dogs and cats are animals. Other commonly discussed principles are the closure principle and the evidence transfer principle.[181]

Knowledge management is the process of creating, gathering, storing, and sharing knowledge. It involves the management of information assets that can take the form of documents, databases, policies, and procedures. It is of particular interest in the field of business and organizational development, as it directly impacts decision-making and strategic planning. Knowledge management efforts are often employed to increase operational efficiency in attempts to gain a competitive advantage.[182] Key processes in the field of knowledge management are knowledge creation, knowledge storage, knowledge sharing, and knowledge application. Knowledge creation is the first step and involves the production of new information. The newly acquired knowledge has to be reliably stored to not become lost or forgotten. This can happen through different means, including books, audio recordings, film, and digital databases. Secure storage facilitates knowledge sharing, which involves the transmission of information from one person to another. For the knowledge to be beneficial, it has to be put into practice. This means that its insights should be used to either improve existing practices or implement new ones.[183]

Knowledge representation is the field of inquiry within artificial intelligence that studies how computer systems can efficiently represent information. It investigates how different data structures and interpretative procedures can be combined to achieve this goal and which formal languages can be used to express knowledge items. Some efforts in this field are directed at developing general languages and systems that can be employed in a great variety of domains while others focus on an optimized representation method within one specific domain. Knowledge representation is closely linked to automatic reasoning because the purpose of knowledge representation formalisms is usually to construct a knowledge base from which inferences are drawn.[184] Influential knowledge base formalisms include logic-based systems, rule-based systems, semantic networks, and frames. Logic-based systems rely on formal languages employed in logic to represent knowledge. They use devices like individual terms, predicates, and quantifiers. For rule-based systems, each unit of information is expressed using a conditional production rule of the form "if A then B". Semantic nets model knowledge as a graph consisting of vertices to represent facts or concepts and edges to represent the relations between them. Frames provide complex taxonomies to group items into classes, subclasses, and instances.[185]

See also

- Epistemic modal logic – subfield of modal logic that is concerned with reasoning about knowledge

- Knowledge falsification – Deliberate misrepresentation of knowledge

- Omniscience – Capacity to know everything

- Outline of knowledge – Overview of and topical guide to knowledge

References

Notes

- ↑ A similar approach was already discussed in Ancient Greek philosophy in Plato's dialogue Theaetetus, where Socrates pondered the distinction between knowledge and true belief but rejected the JTB definition of knowledge.[24]

- ↑ A defeater of a belief is evidence that this belief is false.[40]

Citations

- ↑

- ↑

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 109

- Steup & Neta 2020, Lead Section, § 1. The Varieties of Cognitive Success

- ↑

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.1 The Truth Condition, § 1.2 The Belief Condition

- Klein 1998, § 1. The Varieties of Knowledge

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1b. Knowledge-That

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1. Kinds of Knowledge

- Stanley & Willlamson 2001, pp. 411–412

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 92

- ↑

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 99

- Hetherington 2022a, § 2. Knowledge as a Kind

- ↑

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, Lead Section

- Hannon 2021, Knowledge, Concept of

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- Zagzebski 1999, pp. 92, 96–97

- ↑

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, Lead Section

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 96

- Gupta 2021

- ↑ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 7. Is Knowledge Analyzable?

- ↑

- Pritchard 2013, 3 Defining knowledge

- McCain 2022, Lead Section, § 2. Chisholm on the Problem of the Criterion

- Fumerton 2008, pp. 34–36, The Problem of the Criterion

- ↑

- Stroll 2023, § The Origins of Knowledge, § Analytic Epistemology

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- ↑

- ↑

- Hetherington, § 8. Implications of Fallibilism: No Knowledge?

- Hetherington 2022a, § 6. Standards for Knowing

- Black 2002, pp. 23–32

- ↑

- Klausen 2015, pp. 813–818

- Lackey 2021, pp. 111–112

- ↑

- AHD staff 2022a

- Magee & Popper 1971, pp. 74–75, Conversation with Karl Popper

- ↑

- AHD staff 2022b

- Walton 2005, pp. 59, 64

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Steup & Neta 2020, § 2. What Is Knowledge?

- ↑ Allen 2005, Lead Section

- ↑

- Steup & Neta 2020, Lead Section

- Truncellito 2023, Lead Section

- Moser 2005, p. 3

- ↑

- Allwood 2013, pp. 69–72

- Allen 2005, § Sociology of Knowledge

- Barth 2002, p. 1

- ↑

- Klein 1998, Lead Section, § 3. Warrant

- Zagzebski 1999, pp. 99–100

- ↑

- Allen 2005, Lead Section, § Gettierology

- Parikh & Renero 2017, pp. 93–102, Justified True Belief: Plato, Gettier, and Turing

- Chappell 2019, § 8. Third Definition (D3): 'Knowledge Is True Judgement With an Account': 201d–210a

- ↑

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.1 The Truth Condition

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1b. Knowledge-That, § 5. Understanding Knowledge?

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- ↑

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.2 The Belief Condition

- Klein 1998, § 1. The Varieties of Knowledge

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 93

- ↑

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.3 The Justification Condition, § 6. Doing Without Justification?

- Klein 1998, Lead Section, § 3. Warrant

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 100

- ↑

- Klein 1998, § 2. Propositional Knowledge Is Not Mere True Belief, § 3. Warrant

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5a. The Justified-True-Belief Conception of Knowledge, § 6e. Mere True Belief

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.3 The Justification Condition

- ↑

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.3 The Justification Condition

- Klein 1998, § 3. Warrant

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5a. The Justified-True-Belief Conception of Knowledge, § 6e. Mere True Belief

- ↑

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 1.3 The Justification Condition, § 6.1 Reliabilist Theories of Knowledge

- Klein 1998, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism, § 6. Externalism

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5a. The Justified-True-Belief Conception of Knowledge, § 7. Knowing’s Point

- ↑ Hetherington 2022, Lead Section, § Introduction

- ↑

- Klein 1998, § 5. Defeasibility Theories

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5. Understanding Knowledge?

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 100

- ↑

- Rodríguez 2018, pp. 29–32

- Goldman 1976, pp. 771–773

- Sudduth 2022

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 10.2 Fake Barn Cases

- ↑ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem, § 10.2 Fake Barn Cases

- ↑ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem, § 4. No False Lemmas, § 5. Modal Conditions, § 6. Doing Without Justification?

- ↑ Steup & Neta 2020, § 2.3 Knowing Facts

- ↑ Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem, § 7. Is Knowledge Analyzable?

- ↑

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem, § 7. Is Knowledge Analyzable?

- Durán & Formanek 2018, pp. 648–650

- ↑

- Klein 1998, § 3. Warrant

- Comesaña 2005, p. 367

- ↑ McCain, Stapleford & Steup 2021, p. 111

- ↑

- ↑ Zagzebski 1999, p. 101

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5c. Questioning the Gettier Problem, § 6. Standards for Knowing

- Kraft 2012, pp. 49–50

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 5c. Questioning the Gettier Problem, § 6. Standards for Knowing

- Zagzebski 1999, pp. 103–104

- Sidelle 2001, p. 163

- ↑ Kirkham 1984, pp. 501–503

- ↑

- Ichikawa & Steup 2018, § 3. The Gettier Problem, § 7. Is Knowledge Analyzable?

- Zagzebski 1999, pp. 93–94, 104–105

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 2.3 Knowing Facts

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1. Kinds of Knowledge

- Ronald 1990, p. 40

- Lilley, Lightfoot & Amaral 2004, pp. 162–163

- ↑

- Baehr 2022, Lead Section

- Faber, Maruster & Jorna 2017, p. 340

- Gertler 2021, Lead Section

- Rescher 2005, p. 20

- ↑

- Klein 1998, § 1. The Varieties of Knowledge

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1b. Knowledge-That

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1b. Knowledge-That

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 92

- ↑ Hetherington 2022a, § 1b. Knowledge-That, § 1c. Knowledge-Wh

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1c. Knowledge-Wh

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- ↑

- Morrison 2005, p. 371

- Reif 2008, p. 33

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 93

- ↑ Woolfolk & Margetts 2012, p. 251

- 1 2 Pritchard 2013, 1 Some preliminaries

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1. Kinds of Knowledge

- Stroll 2023, § The Nature of Knowledge

- Stanley & Willlamson 2001, pp. 411–412

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1d. Knowing-How

- Pritchard 2013, 1 Some preliminaries

- ↑

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 2.2 Knowing How

- Pavese 2022, Lead Section, § 6. The Epistemology of Knowledge-How

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1a. Knowing by Acquaintance

- Stroll 2023, § St. Anselm of Canterbury

- Zagzebski 1999, p. 92

- ↑

- Peels 2023, p. 28

- Heydorn & Jesudason 2013, p. 10

- Foxall 2017, p. 75

- Hasan & Fumerton 2020

- DePoe 2022, Lead Section, § 1. The Distinction: Knowledge by Acquaintance and Knowledge by Description

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1a. Knowing by Acquaintance

- ↑

- Hasan & Fumerton 2020, introduction

- Haymes & Özdalga 2016, pp. 26–28

- Miah 2006, pp. 19–20

- Alter & Nagasawa 2015, pp. 93–94

- Hetherington 2022a, § 1a. Knowing by Acquaintance

- ↑

- Stroll 2023, § A Priori and a Posteriori Knowledge

- Baehr 2022, Lead Section

- Russell 2020, Lead Section

- ↑

- Baehr 2022, Lead Section

- Moser 2016, Lead Section

- ↑ Baehr 2022, Lead Section

- ↑

- Russell 2020, Lead Section

- Baehr 2022, Lead Section

- ↑ Moser 2016, Lead Section

- ↑

- Baehr 2022, § 1. An Initial Characterization, § 4. The Relevant Sense of 'Experience'

- Russell 2020, § 4.1 A Priori Justification Is Justification That Is Independent of Experience

- ↑

- Baehr 2022

- Russell 2020, § 4.1 A Priori Justification Is Justification That Is Independent of Experience

- ↑

- Woolf 2013, pp. 192–193

- Hirschberger 2019, p. 22

- ↑

- Moser 1998, § 2. Innate concepts, certainty and the a priori

- Markie 1998, § 2. Innate ideas

- ↑ Baehr 2022, § 1. An Initial Characterization, § 6. Positive Characterizations of the A Priori

- ↑

- Gertler 2021, Lead Section, § 1. The Distinctiveness of Self-Knowledge

- Gertler 2010, p. 1, 1. Introduction

- McGeer 2001, pp. 13837–13841

- ↑

- Gertler 2021a

- Morin & Racy 2021, pp. 373–374, 15. Dynamic Self-processes – Self-knowledge

- Kernis 2013, p. 209

- ↑

- Evans & Foster 2011, pp. 721–725

- Rescher 2005, p. 20

- Cox & Raja 2011, p. 134

- Leondes 2001, p. 416

- ↑

- ↑ Schneider & McGrew 2022, pp. 115–116

- ↑

- 1 2

- APA staff 2022

- Hunter 2009, pp. 151–153, Situated Knowledge

- ↑ Barnett 2006, pp. 146–147, Vocational Knowledge and Vocational Pedagogy

- ↑ Hunter 2009, pp. 151–153, Situated Knowledge

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- Stroll 2023, § Occasional and Dispositional Knowledge

- Bartlett 2018, pp. 1–2

- Schwitzgebel 2021

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- Kern 2017, pp. 8–10, 133

- Spaulding 2016, pp. 223–224, Imagination Through Knowledge

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 3. Ways of Knowing

- Stroll 2023, § The Origins of Knowledge

- O’Brien 2022, Lead Section

- ↑ Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.1 Perception

- ↑ Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.2 Introspection

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 3. Ways of Knowing

- Stroll 2023, § The Origins of Knowledge

- ↑

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.3 Memory

- Audi 2002, pp. 72–75, The Sources of Knowledge

- ↑

- Gardiner 2001, pp. 1351–1352

- Michaelian & Sutton 2017

- ↑ Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.3 Memory

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 3d. Knowing by Thinking-Plus-Observing

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.4 Reason

- ↑

- Audi 2002, pp. 85, 90–91, The Sources of Knowledge

- Markie & Folescu 2021, Lead Section, § 1. Introduction

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 3c. Knowing Purely by Thinking

- Stroll 2023, § Rationalism and Empiricism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.4 Reason

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 3a. Innate Knowledge

- Stroll 2023, § Innate and Acquired Knowledge

- ↑

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 5.5 Testimony

- Leonard 2021, Lead Section, § 1. Reductionism and Non-Reductionism

- Green 2022, Lead Section

- ↑

- Hasan & Fumerton 2018, Lead Section, 2. The Classical Analysis of Foundational Justification

- Fumerton 2022, § Summary

- 1 2 3

- Klein 1998, Lead Section, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 4. The Structure of Knowledge and Justification

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- ↑

- ↑

- Klein 1998, Lead Section, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 4.1 Foundationalism

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- ↑

- ↑

- Klein 1998, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 4. The Structure of Knowledge and Justification

- Lehrer 2015, 1. The Analysis of Knowledge

- 1 2

- Klein 1998, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 4. The Structure of Knowledge and Justification

- ↑

- ↑ Klein 1998, § 4. Foundationalism and Coherentism

- ↑

- Degenhardt 2019, pp. 1–6

- Pritchard 2013, 2 The value of knowledge

- Olsson 2011, pp. 874–875

- ↑ Pritchard 2013, 2 The value of knowledge

- ↑

- ↑ Degenhardt 2019, pp. 1–6

- ↑

- Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022

- Olsson 2011, pp. 874–875

- ↑

- Olsson 2011, pp. 874–875

- Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022

- Plato 2002, pp. 89–90, 97b–98a

- ↑ Olsson 2011, p. 875

- ↑ Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, Lead Section, § 6. Other Accounts of the Value of Knowledge

- ↑

- Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022

- Olsson 2011, p. 874

- Pritchard 2007, pp. 85–86

- ↑ Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, § 2. Reliabilism and the Meno Problem, § 3. Virtue Epistemology and the Value Problem

- ↑ Turri, Alfano & Greco 2021

- ↑ Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, § 2. Reliabilism and the Meno Problem

- ↑

- Pritchard, Turri & Carter 2022, § 3. Virtue Epistemology and the Value Problem

- Olsson 2011, p. 877

- Turri, Alfano & Greco 2021, § 6. Epistemic Value

- ↑

- Klein 1998, § 8. The Epistemic Principles and Scepticism

- Hetherington 2022a, § 4. Sceptical Doubts About Knowing

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 6.1 General Skepticism and Selective Skepticism

- ↑

- Attie-Picker 2020, pp. 97–98

- Perin 2020, pp. 285–286

- ↑

- Windt 2021, § 1.1 Cartesian Dream Skepticism

- Klein 1998, § 8. The Epistemic Principles and Scepticism

- Hetherington 2022a, § 4. Sceptical Doubts About Knowing

- 1 2 Steup & Neta 2020, § 6.1 General Skepticism and Selective Skepticism

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 6. Standards for Knowing

- Klein 1998, § 8. The Epistemic Principles and Scepticism

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 6.1 General Skepticism and Selective Skepticism

- ↑ Stroll 2023, § Skepticism

- ↑

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 6.2 Responses to the Closure Argument

- Lycan 2019, pp. 21–22, 5–36

- ↑

- McDermid 2023

- Misak 2002, p. 53

- Hamner 2003, p. 87

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 4. Sceptical Doubts About Knowing

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 6.1 General Skepticism and Selective Skepticism

- ↑

- Hetherington 2022a, § 4. Sceptical Doubts About Knowing

- Stroll 2023, § Skepticism, § Perception and Knowledge

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 6.1 General Skepticism and Selective Skepticism

- ↑ Hetherington 2022a, § 4. Sceptical Doubts About Knowing

- 1 2

- Pritchard 2013, pp. 115–118, 11 Scientific Knowledge

- Moser 2005, p. 385, 13. Scientific Knowledge

- ↑ Moser 2005, p. 386, 13. Scientific Knowledge

- ↑

- Moser 2005, p. 390, 13. Scientific Knowledge

- Hatfield 1996, Scientific method

- Beins 2017, pp. 8–9

- Hepburn & Andersen 2021

- ↑

- ↑

- Pritchard 2013, pp. 123–125, 11 Scientific Knowledge

- Niiniluoto 2019

- ↑

- Burke 2015, 1. Knowledges and Their Histories: § History and Its Neighbours, 3. Processes: § Four Stages, 3. Processes: § Oral Transmission

- Doren 1992, pp. xvi–xviii

- Daston 2017, pp. 142–143

- Mulsow 2018, p. 159

- ↑

- Bowen, Gelpi & Anweiler 2023, § Introduction, Prehistoric and Primitive Cultures

- Bartlett & Burton 2007, p. 15

- Fagan & Durrani 2016, p. 15

- Doren 1992, pp. 3–4

- ↑

- Doren 1992, pp. xxiii–xxiv, 3–4

- Friesen 2017, pp. 17–18

- Danesi 2013, pp. 168–169

- Steinberg 1995, pp. 3–4

- Lanzer 2018, p. 7

- ↑

- Doren 1992, pp. xxiii–xxiv, 3–4, 29–30

- Conner 2009, p. 81

- ↑

- Burke 2015, 2. Concepts: § Authorities and Monopolies

- Kuhn 1992, p. 106

- Lanzer 2018, p. 7

- ↑

- ↑

- Johnson & Stearns 2023, pp. 5, 43–44, 47

- Esposito 2003, Madrasa

- ↑

- Trefil 2012, pp. 63–64, Islamic Science

- Ashraf 2023, pp. 101–102

- ↑ Aqil, Babekri & Nadmi 2020, p. 156, Morocco: Contributions to Mathematics Education From Morocco

- ↑ Cosman & Jones 2009, p. 148

- ↑ Gilliot 2018, p. 81

- ↑

- Bowen, Gelpi & Anweiler 2023, § The Development of the Universities

- Kemmis & Edwards-Groves 2017, p. 50

- ↑ Power 1970, pp. 243–244

- ↑ Ashraf 2023, p. 159

- ↑

- Steinberg 1995, p. 5

- Danesi 2013, pp. 169–170

- ↑

- Doren 1992, pp. xxiv–xxv, 184–185

- Lanzer 2018, p. 7

- ↑

- Doren 1992, pp. xxiv–xxv, 213–214

- Lanzer 2018, p. 7

- ↑

- Lanzer 2018, p. 8

- Danesi 2013, pp. 178–181

- ↑ Clark 2022, Lead Section, § 2. The Evidentialist Objection to Belief in God

- 1 2 Penelhum 1971, 1. Faith, Scepticism and Philosophy

- ↑

- Clark 2022, Lead Section

- Forrest 2021, Lead Section, § 1. Simplifications

- ↑

- Clark 2022, Lead Section, § 2. The Evidentialist Objection to Belief in God

- Forrest 2021, Lead Section, § 2. The Rejection of Enlightenment Evidentialism

- Dougherty 2014, pp. 97–98

- ↑

- Clark 2022, § 2. The Evidentialist Objection to Belief in God

- Forrest 2021, Lead Section, 2. The Rejection of Enlightenment Evidentialism

- ↑ Clark 2022, § 2. The Evidentialist Objection to Belief in God

- ↑ Stevenson 2003, pp. 72–73

- ↑

- Paden 2009, pp. 225–227, Comparative Religion

- Bouquet 1962, p. 1

- ↑

- Carson & Cerrito 2003, p. 164

- Delahunty & Dignen 2012, p. 365, Tree of Knowledge

- Blayney 1769, Genesis

- ↑ Vost 2016, pp. 75–76

- ↑

- Campo 2009, p. 515

- Swartley 2005, p. 63

- ↑

- Burton 2002, pp. 326–327

- Chaudhary 2017, pp. 202–203, Avijjā)

- Chaudhary 2017, pp. 1373–1374, Wisdom (Buddhism)

- ↑

- Chaudhary 2017, pp. 202–203, Avijjā)

- Chaudhary 2017, pp. 1373–1374, Wisdom (Buddhism)

- ↑

- ↑

- Allwood 2013, pp. 69–72, Anthropology of Knowledge

- Boyer 2007, 1. Of Dialectical Germans and Dialectical Ethnographers: Notes from an Engagement with Philosophy

- ↑ Cohen 2010, pp. S193–S202

- 1 2 3 Allwood 2013, pp. 69–72, Anthropology of Knowledge

- ↑

- Allwood 2013, pp. 69–72, Anthropology of Knowledge

- Barth 2002, p. 1

- ↑ Barth 2002, pp. 1–2

- ↑

- Allwood 2013, pp. 69–72, Anthropology of Knowledge

- Cohen 2010, pp. S193–S202

- ↑

- Allwood 2013, pp. 69–72, Anthropology of Knowledge

- Barth 2002, pp. 1–4

- Kuruk 2020, p. 25

- ↑

- Allwood 2013, pp. 69–72, Anthropology of Knowledge

- Hansen 1982, p. 193

- 1 2

- ↑

- Lee 2017, p. 67

- Dreyer 2017, pp. 1–7

- ↑ Weisberg 2021

- ↑

- Steup & Neta 2020, § 3.3 Internal Vs. External

- Das & Salow 2018, pp. 3–4

- Dokic & Égré 2009, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Klein 1998, § 7. Epistemic Principles

- ↑

- ↑

- Suzanne 2021, pp. 114–115

- Choo 2002, pp. 503–504

- Witzel 2004, p. 252

- ↑

- Castilho & Lopes 2009, p. 287

- Kandel 1992, pp. 5–6

- Cai et al. 2021, p. 21

- ↑

- Castilho & Lopes 2009, pp. 287–288

- Kandel 1992, pp. 5–6

- Akerkar & Sajja 2010, pp. 71–72

Sources

- AHD staff (2022). "Ignorance". The American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- AHD staff (2022a). "Knowledge". The American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- AHD staff (2022b). "Knowledge Base". The American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- AHD staff (2022c). "Intelligence". The American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- Akerkar, Rajendra; Sajja, Priti (2010). Knowledge-Based Systems. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-0-7637-7647-3.

- Allen, Barry (2005). "Knowledge". In Horowitz, Maryanne Cline (ed.). New Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Vol. 3. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 1199–1204. ISBN 978-0-684-31377-1. OCLC 55800981. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017.

- Allwood, Carl Martin (2013). "Anthropology of Knowledge". The Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 69–72. doi:10.1002/9781118339893.wbeccp025. ISBN 978-1-118-33989-3. Archived from the original on 26 September 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- Alter, Torin; Nagasawa, Yujin (2015). Consciousness in the Physical World: Perspectives on Russellian Monism. Oxford University Press. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-0-19-992736-4. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- APA staff (2022). "APA Dictionary of Psychology: Situated Knowledge". Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- Aqil, Moulay Driss; Babekri, El Hassane; Nadmi, Mustapha (25 June 2020). "Morocco: Contributions to Mathematics Education From Morocco". In Vogeli, Bruce R.; Tom, Mohamed E. A. El (eds.). Mathematics And Its Teaching In The Muslim World. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-314-679-2.

- Ashraf, Mirza Iqbal (2023). Progression of Knowledge in Western Civilization. Archway Publishing. ISBN 978-1-6657-4959-6.

- Attie-Picker, Mario (2020). "Does Skepticism Lead to Tranquility? Exploring a Pyrrhonian Theme". Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Volume 3: 97–125. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198852407.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-19-885240-7.

- Audi, Robert (2002). "The Sources of Knowledge". The Oxford Handbook of Epistemology. Oxford University Press. pp. 71–94. ISBN 978-0-19-513005-8. Archived from the original on 12 June 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- Awad, Elias M.; Ghaziri, Hassan (2003). Knowledge Management. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-93-325-0619-0.

- Baehr, Jason S. (2022). "A Priori and A Posteriori". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- Barnett, Michael (2006). "Vocational Knowledge and Vocational Pedagogy". In Young, Michael; Gamble, Jeanne (eds.). Knowledge, Curriculum and Qualifications for South African Further Education. HSRC Press. ISBN 978-0-7969-2154-3.

- Barth, Fredrik (2002). "An Anthropology of Knowledge". Current Anthropology. 43 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1086/324131. hdl:1956/4191. ISSN 0011-3204.

- Bartlett, Gary (2018). "Occurrent States". Canadian Journal of Philosophy. 48 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/00455091.2017.1323531. S2CID 220316213. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- Bartlett, Steve; Burton, Diana (2007). Introduction to Education Studies (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-2193-0.

- Becerra-Fernandez, Irma (2010). Knowledge Management: Systems and Processes. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-2857-2.

- Beins, Bernard C. (19 September 2017). Research Method: A Tool for Life. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-43623-6.

- Black, Tim (2002). "Relevant Alternatives and the Shifting Standards of Knowledge". Southwest Philosophy Review. 18 (1): 23–32. doi:10.5840/swphilreview20021813. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- Blayney, Benjamin, ed. (1769). "Genesis". The King James Bible. Oxford University Press. OCLC 745260506. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- Bouquet, Alan Coates (1962). Comparative Religion: A Short Outline. CUP Archive. p. 1. OCLC 927397955.

- Bowen, James; Gelpi, Ettore; Anweiler, Oskar (2023). "Education". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- Bowker, John (1 January 2003). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280094-7.

- Boyer, Dominic (2007). "1. Of Dialectical Germans and Dialectical Ethnographers: Notes from an Engagement with Philosophy". In Harris, Mark (ed.). Ways of Knowing: Anthropological Approaches to Crafting Experience and Knowledge. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-364-0.

- Burke, Peter (2015). What Is the History of Knowledge?. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-5095-0306-3.

- Burton, David (2002). "Knowledge and Liberation: Philosophical Ruminations on a Buddhist Conundrum". Philosophy East and West. 52 (3): 326–345. doi:10.1353/pew.2002.0011. ISSN 0031-8221. JSTOR 1400322. S2CID 145257341. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.