Kurt Chew-Een Lee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Kurt |

| Born | January 21, 1926 San Francisco, California, US |

| Died | March 3, 2014 (aged 88) Washington, D.C., US |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1944–1968 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Machine-Gun Platoon of Baker Company, 1st Battalion 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division (Reinforced) |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | |

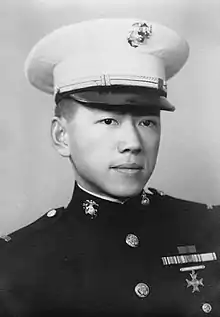

Kurt Chew-Een Lee (traditional Chinese: 呂超然; simplified Chinese: 吕超然; pinyin: Lǚ Chāorán (January 21, 1926 – March 3, 2014) was the first Asian American to be commissioned as a regular officer in the United States Marine Corps. Lee earned the Navy Cross under fire in Korea in September 1950, serving in the 1st Battalion 7th Marines.

Lee and his younger brothers Chew-Mon Lee (Chinese: 呂超民)[2] and Chew-Fan Lee all earned bravery medals in the Korean War.

Early life

Chew-Een Lee was born in 1926 in San Francisco[3] and grew up in Sacramento, California.[4] Lee's father was M. Young Lee, a native of Guangzhou (Canton) who first emigrated to the Territory of Hawaii in the 1920s and then California. Once established in America, M. Young Lee traveled to China to honor an arranged marriage.[5] He then brought his bride to California and worked as a distributor of farm produce to hotels and restaurants. According to another source, both Lee and his father were born in Hawaii.[6] Lee's brother Chew-Fan Lee was born in 1927 in Sacramento.[7] In 1928, a third son was born to the family: Chew-Mon Lee.[7] The Lee family included three daughters: Faustina, Betty and Juliet.[8]

Military career

World War II

At the time of the Attack on Pearl Harbor, Chew-Een Lee was a high school student going by the nickname "Kurt", associated with the Junior Reserve Officers' Training Corps (Junior ROTC). In 1944 when he was an 18-year-old student of mining engineering, Lee joined the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC).[4] Small for a recruit, Lee was about 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 m) tall, and around 130 pounds (59 kg), but he was wiry and muscular.[9] At the Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego, Lee was assigned the task of learning the Japanese language. At graduation, he was retained as the language class instructor, a decision that disappointed Lee because he wanted to ship out and fight in the war. He earned the rank of sergeant and had just been accepted to officer training class when World War II ended.

From October 1945 to April 1946, Lee was enrolled in The Basic School, newly reactivated for USMC officer training. Second Lieutenant Lee graduated to become the first non-white officer and the first Asian-American officer in the Marine Corps.[4] He deployed to Guam and China to interrogate Japanese prisoners of war.[7]

Korean War

At the start of the Korean War, First Lieutenant Lee was in command of the 1st Platoon, Company B, 1st Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment training at Camp Pendleton under Colonel Homer Litzenberg. Soon, his unit received notice that it would ship out for the war zone at the beginning of September. Lee wanted to set a strong example of a fighting Chinese American. He said he "wanted to dispel the notion about the Chinese being weak, meek, and obsequious."[10] He did not expect to survive the war, and intended his death to "be honorable, be spectacular".[4]

Lee's brother Chew-Mon Lee had by this time joined the U.S. Army and was also training for Korea. Lee described the difficulty of leaving home as the family's first-born son:

I came from a family of limited means. My father, whose Chinese name was Brilliant Scholar, distributed fruit and vegetables to restaurants and hotels in Sacramento. He stayed home from work that morning, and my mother, whose Chinese name was Gold Jade, made a special meal. There was an awkward moment when the clock on the wall said it was time to depart. My mother was very brave. She said nothing. My father had been reading the Chinese newspaper, or pretending to. He was a tough guy, my father, and I admired his toughness. He rose from his chair and shook my hand abruptly. He tried to talk, but couldn't, and that's when my mother broke down.[11]

Battle of Inchon

Lee's unit shipped out on September 1, 1950, before the Battle of Inchon. For two weeks he drilled his men day and night on the deck of the ship, enduring derision from the other platoon leaders.[12] After arriving in Japan for final battle preparations, Lee's superiors tried to reassign him as staff officer handling translation duties. Lee insisted that he was only there to "fight communists", and was allowed to retain command of his platoon.[7]

The 1st Battalion 7th Marines, including Lee, landed at Inchon on September 21, 1950, to attack the North Koreans and force them to retreat northwards. The People's Republic of China sent troops to stiffen the North Korean fighting response. On the night of November 2–3 in the Sudong Gorge, Lee's unit was attacked by Chinese forces. Lee kept his men focused by directing them to shoot at the enemy's muzzle flashes. Following this, Lee single-handedly advanced upon the enemy front and attacked their positions one by one to draw their fire and reveal themselves. His men fired at the muzzle flashes and inflicted casualties, forcing the enemy to retreat. While advancing, Lee shouted to the enemy in Mandarin Chinese to sow confusion and then attacked with hand grenades and gunfire. Lee was wounded in the knee and in the morning light was shot in the right elbow by a sniper, shattering the bones. He was evacuated to a MASH unit (an army field hospital) outside of Hamhung. For bravely attacking the enemy and saving his men, Lee was awarded the Navy Cross, the second highest honor given for combat bravery.[13]

Lee was under hospital care for five days when he learned he was to be sent to Japan for recuperation. Unauthorized, he and another wounded marine took an army jeep and drove it back to his unit, walking the last 10 miles (16 km) when the jeep ran out of gas.[12] He was assigned to command the 2nd Rifle Platoon whose officer had been wounded.[4] Lee exercised his platoon in combat maneuvers while his arm was in a sling.[4] This extra training helped his platoon take a leading role in heavy fighting a month later.[4]

Sometime in mid-November 1950, Lee met up with his brother U.S. Army First Lieutenant Chew-Mon Lee at a marine field headquarters.[7] Both men had been wounded and were resting up before further battle. The Sacramento Bee published a photograph and a brief report of the meeting.[14] Chew-Mon Lee addressed his brother respectfully as daigo, meaning "elder brother", and gave him a gift of army-issue 30-round "banana" magazines which could be taped together to make quicker reloads without the needs of going for one's ammo pouch. This was regarded as superior to the USMC regulation 15-round magazines then in service.[15] A week or two later, on November 30, 1950, Chew-Mon Lee performed heroically in battle, earning the Distinguished Service Cross.[16]

Battle of Chosin Reservoir

Late on December 2 after several days of exhausting combat during the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, Lee's platoon was given the task of spearheading a 500-man thrust against the Chinese forces in an effort to relieve the outnumbered Fox Company of 2nd Battalion 7th Marines trapped on Fox Hill, part of Toktong Pass and strategic to controlling the Chosin Reservoir road. Lee's relief force was given heavier loads to carry through the snow, up and down lightly wooded hills, through extreme cold (−20 °F, −29 °C), and under the very limited visibility of snow blizzard and darkness. Lieutenant Colonel Ray Davis, commanding officer of 1st Battalion, had no instructions for Lieutenant Lee on how to accomplish the mission except to stay off the roads with their heavily reinforced roadblocks. As point man of 2nd Rifle Platoon in Baker Company, Lee used only his compass to guide his way, leading 1st Battalion in single file.[17] Suddenly pinned down by heavy enemy fire coming from a rocky hill, Lee refused to be delayed in his mission. He directed the men to attack the hill with "marching fire", a stratagem used by General George S. Patton in which troops continue to advance as they apply just enough suppressive fire to keep the enemy's heads down. Upon reaching the rocky hill, Lee and the battalion charged, attacking enemy soldiers in their foxholes. Lee, with his right arm still in a cast, shot two enemy soldiers on his way to the top. When he reached the top, he noticed that the other side of the hill was covered with enemy foxholes facing the other way in expectation of an attack from the road, but the foxholes were now empty and the enemy soldiers were over 400 yards (370 m) away in rout because of the fearfully sudden 1st Battalion attack from their rear.[4]

Following this success, communication was established with nearby Fox Company on Fox Hill. 1st Battalion directed mortar fire against the enemy and called in an airstrike, then Lee led Baker Company forward in an attack which forced a path to Fox Company. During this attack Lee took a bullet to the upper part of his right arm, above the cast on his elbow.[18] Regrouping his men, Lee led Baker Company in more firefights against pockets of enemy soldiers in the Toktong Pass area, securing the road. On December 8, 1950, a Chinese machine gunner targeted Lee, wounding him seriously enough to end his Korean War service.[4] Lieutenant Colonel Davis received the Medal of Honor for commanding the relief of Fox Company. Lee was awarded the Silver Star.

Throughout Lee's time in Korea, his brother Chew-Fan Lee was a student at the University of California, San Francisco and School of Pharmacy. Upon graduating in 1951, Chew-Fan Lee joined the Medical Service Corps (United States Army) at the rank of lieutenant, despite being a pacifist. In Korea, he performed bravely in action and was awarded the Bronze Star Medal.[7][14] He exploits are recounted in Colder Than Hell: A Marine Rifle Company at Chosin Reservoir (1996).[19]

Vietnam War

Lee served at The Basic School from 1962 to 1965, beginning as commanding officer of the Enlisted Instructor Company at the rank of captain. He earned the rank of major on January 1, 1963, at which time he was made chief of the Platoon Tactics Instruction Group. In his 27 months at this position he trained future generals Charles "Chuck" Krulak and John "Jack" Sheehan.[4] Lee served overseas in South Vietnam during 1965–1966 as Division Combat Intelligence Officer for 3rd Marine Division, III Marine Amphibious Force.[4] He organized a division-level translation team for quickly processing foreign language documents captured by marine field units.[4]

Later life and death

Lee retired from military service at the rank of major in 1968[10] and worked a civilian job with New York Life Insurance Company for seven years. During this period, Lee's mother died in Sacramento, and Lee's brother Chew-Mon Lee committed suicide in 1972 at the rank of colonel,[2] while serving as army attaché for the United States Embassy in Taipei, Taiwan.[20] His brother Chew-Fan Lee advanced in his career as hospital pharmacist. In 1975, Lee began working as a regulatory compliance coordinator for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association; a position he held for almost two decades.[4][21] Lee was married twice, producing no children. He had a step-daughter from his second marriage.[21] Lee retired from his civilian career, living near Washington, D.C. in Arlington, Virginia.

Legacy

The vigorous fighting spirit that Lee gave to his USMC company resulted in it being allowed to keep the name "Baker Company" even after the U.S. military switched in 1956 from the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet (B for Baker) to the NATO phonetic alphabet (B for Bravo).[4] In a 2002 speech about the Chosin Reservoir battle, General Ray Davis said that Lee was the bravest marine he ever knew.[4]

In 2000, the California Military Museum mounted an exhibit describing the bravery and military service of the three Lee brothers.[14] Lee is a member of the Legion of Valor, and represented the group in a meeting with President George W. Bush in 2007.[14]

The story of Lee's bravery in the Korean War was the subject of a documentary produced by the Smithsonian Channel.[25] The documentary, titled Uncommon Courage: Breakout at Chosin, was broadcast on Memorial Day, May 31, 2010. David Royle of the Smithsonian Channel said that the filmmakers interviewed a number of veterans who served alongside Lee, many of whom believed that "he should have been awarded the Medal of Honor."[10] Joe Owen was one of the marines fighting under Lee's leadership, and he told Smithsonian Channel documentarians that if it had not been for the death of Lee's company commander soon after the November 2–3 action, Lee would have been properly nominated for the Medal of Honor, the highest military honor of the United States.

Lee gave his final film interview for the Korean War documentary "Finnigan's War", directed by Conor Timmis.

Early in his career, Lee's superior officers criticized him for his aggressive chip-on-shoulder attitude.[7] Lee maintained the pugnacious stance throughout his life. Lee responded to critics by saying that the chip is "my teaching tool to dispel ignorance."[4]

Awards

Lee received decorations for bravery and service in the Korean War and in Vietnam. In addition to the Navy Cross, he also received the Silver Star and the Navy Marine Corps Commendation Ribbon with "V" Device (for valor in combat).[26]

Navy Cross Citation

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to First Lieutenant Kurt Chew-Een Lee (MCSN: 0-48880), United States Marine Corps, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy of the United Nations while serving as Commanding Officer of a Machine-Gun Platoon of Company B, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division (Reinforced), in action against enemy aggressor forces in the Republic of Korea, on 2 and 3 November 1950. Immediately taking countermeasures when a numerically superior enemy force fiercely attacked his platoon and overran its left flank during the defense of strategic terrain commanding approaches to the main supply route south of Sudong, first Lieutenant Lee boldly exposed himself to intense hostile automatic weapons, grenade and sniper small-arms fire to carry out a personal reconnaissance, well in advance of his own lines, in order to re-deploy the machine-gun posts within the defensive perimeter. Momentarily forced back by extremely heavy opposition, he quickly reorganized his unit and, instructing his men to cover his approach, bravely moved up an enemy held slope in a deliberate attempt to draw fire and thereby disclose hostile troop positions. Despite serious wounds sustained as he pushed forward, First Lieutenant Lee charged directly into the face of the enemy fire and, by his dauntless fighting spirit and resourcefulness, served to inspire other members of his platoon to heroic efforts in pressing a determined counterattack and driving the hostile forces from the sector. His outstanding courage, brilliant leadership and unswerving devotion to duty were contributing factors in the success achieved by his company and reflect the highest credit upon First Lieutenant Lee and the United States Naval Service.[27]

Silver Star Citation

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to First Lieutenant Kurt Chew-Een Lee (MCSN: 0-48880), United States Marine Corps, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity while serving as a Platoon Leader with Company B, First Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division (Reinforced), in action against enemy aggressor forces in Korea from 27 November to 8 December 1950. Although sick and in a weakened condition from a previous combat wound, First Lieutenant Lee refused hospitalization and unflinchingly led his unit across trackless, frozen wastes of rocky mountain ridges toward a beleaguered Marine company. Through his indomitable spirit, he contributed materially to the success of the epic night march of his battalion which resulted in the relief of the isolated Marine unit and the securing of vital ground. On 2 December 1950 when the leading elements of his company were pinned down under intense enemy fire from a rocky hill mass, he skillfully maneuvered his platoon forward in an attack in the face of the heavy fire, personally accounting for two enemy dead and providing such aggressive and inspirational leadership that fire superiority was regained and the enemy was routed. On 8 December 1950, First Lieutenant Lee's platoon was pinned down by intense hostile fire while attacking south on the main service road from Koto-ri. Observing that the heavy fire was inflicting numerous casualties, he exposed himself to the deadly fire to move among his troops, shouting words of encouragement and directing a withdrawal to covered positions. Assured that the last of his wounded was under cover, he was seeking shelter for himself when he was struck down and severely wounded by a burst of enemy machine gun fire. By his daring initiative and great personal valor throughout, First Lieutenant Lee served to inspire all who observed him and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.[28]

See also

References

- ↑ "Burial detail". ANC Explorer. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- 1 2 "畸戀難自拔 多情空餘恨 武官之死感情糾紛 吳姓女子兩度自殺" [Military Attaché died of Emotional Entanglement]. United Daily News. 1972-05-10. p. 03.

- ↑ "Kurt Lee Collection". Veterans History Project. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Robison, Michael (February 1, 2011). "Chinese American Hero: Major Kurt Chew-Een Lee". AsianWeek. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012.

- ↑ Drury, 2009, p. 254

- ↑ Tucker, Neely (May 30, 2010). "Korean War documentary, 'Uncommon Courage: Breakout at Chosin,' debuts". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Drury, Bob; Clavin, Tom; Drury, Tom (2009). The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat. Grove Press. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-0-8021-4451-5.

- ↑ "Part Two: The One Week Visit of American Military Hero – Major Kurt Chew-Een Lee" (PDF). Cathay Chronicle. American Legion, Cathay Post No. 384. 2 (4). April 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-26.

- ↑ Drury, 2009, p. 255

- 1 2 3 Perry, Tony (May 31, 2010). "A tale of Korean War heroism: U.S. Marine Chew-Een Lee's bravery at the battle of the Chosin Reservoir is a focus of Smithsonian Channel documentary". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Russ, Martin (2000). Breakout: The Chosin Reservoir Campaign, Korea 1950 (2 ed.). Penguin Books. p. 9. ISBN 0-14-029259-4. Sample text hosted by The New York Times.

- 1 2 Drury, 2009, pp. 252–253

- ↑ "U.S. Military Awards for Valor - Top 3". valor.defense.gov. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- 1 2 3 4 Chinese American Museum of Northern California (2000). Sacramento's Chinatown. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 95, 102–103. ISBN 0-7385-8066-X.

- ↑ Owen, Joseph R. (2000). Colder Than Hell: A Marine Rifle Company at Chosin Reservoir. Naval Institute Press. p. 86. ISBN 1-55750-416-4.

- ↑ "Distinguished Service Cross Citation for Chew-Mon Lee". Arlington National Cemetery. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ↑ Drury, 2009, p. 262

- ↑ Drury, 2009, p. 270

- ↑ William Yardley (March 10, 2014). "Kurt Chew-Een Lee, Singular Marine, Dies at 88". The New York Times. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

Among other books, his exploits are recounted in "Colder Than Hell: A Marine Rifle Company at Chosin Reservoir" (1996), by Joseph R. Owen.

- ↑ United States Department of State (October 1971). Foreign Service List. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 7.

- 1 2 Tucker, Neely (May 30, 2010). "The Marine who fought his own people; 'Uncommon Courage' in Korea: Documentary recalls bravery amid the horrors of battle at Chosin". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 11, 2014.

- ↑ "First Asian American in United States Marine Corps passes away | abc7news.com". Archived from the original on 2014-03-05. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- ↑ "Obituary: Maj. Kurt Chew-Een Lee, 88, was Korean War hero - Obituaries - the Sacramento Bee". Archived from the original on 2014-03-05. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ↑ Park, Madison (March 6, 2014). "Maj. Kurt Chew-een Lee, Asian-American Marines trailblazer dies at 88". CNN. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Uncommon Courage: Breakout At Chosin". Smithsonian Channel. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ↑ "YouTube: Happy 235th Birthday Marine Corps". U.S. Marine Corps.

- ↑ Navy Cross Citation: http://valor.militarytimes.com/recipient.php?recipientid=5719

- ↑ Silver Star Citation: http://valor.militarytimes.com/recipient.php?recipientid=5719

External links

- Kurt Chew-Een Lee at IMDb

- "Asian Americans in the United States Military during the Korean War". New Jersey Korean War Memorial. New Jersey Department of Military & Veterans Affairs. Photograph of Lieutenant Lee in Korea, 1950

- Dávila, Robert D. (March 5, 2014). "Obituary: Maj. Kurt Chew-Een Lee, 88, was Korean War hero". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.