The Kylchap steam locomotive exhaust system was designed and patented by French steam engineer André Chapelon, using a second-stage nozzle designed by the Finnish engineer Kyösti Kylälä and known as the Kylälä spreader; thus the name KylChap for this design.

Construction

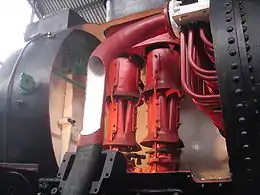

The Kylchap exhaust consists of four stacked nozzles, the first exhaust nozzle (UK: blastpipe) blowing exhaust steam only and known as the primary nozzle, this being a Chapelon design using four triangular jets. This exhausts into the second stage, the Kylälä spreader, which mixes the exhaust steam with some of the smokebox gases; this then exhausts into a third stage, designed by Chapelon, that mixes the resulting steam/smokebox gases mixture with yet more smokebox gases. The four nozzles of this then exhaust into the fourth stage, the classic chimney (U.S.: stack) bell-mouth.

Theory

It was Chapelon's theory that such a multi-stage mixing and suction arrangement would be more efficient than the single stage arrangement hitherto popular in steam locomotive draughting, in which an exhaust nozzle simply is fired up the middle of the stack bell-mouth. It would also ensure a more even flow through all the firetubes, rather than concentrating the suction on one area. The efficiency of the Kylchap system relied on careful proportioning of its components, and perfect alignment and concentricity.

Examples of use

France

Chapelon developed the Kylchap exhaust in 1926 when it was tested on compound Pacifics of the 4500 and 3500 classes and a simple expansion Pacific of the 3591 class, producing significant improvements in steaming and in one case a 41% reduction in back-pressure. However, it first came into prominence in 1929 when applied to compound Pacific No 3566 which combined enlarged steam circuits, increased superheat, feedwater heater, thermic syphon, Lentz poppet valves with double Kylchap exhaust extractors and chimneys. On test in November 1929, the locomotive's indicated power output was found to have increased by over 60%, from 1850 ihp to 3000 ihp while its fuel and water consumption had improved by 25% compared to unrebuilt engines of the same class. These results made Chapelon's name and 3566 became well known both within France and in most countries of the Western world.[1]

Great Britain

Sir Nigel Gresley of the LNER became a proponent when he incorporated double Kylchap exhausts into four of his A4 Pacifics, including the world speed record holder Mallard. Arthur Peppercorn's post-war LNER Pacifics also incorporated them, including preserved A2 532 Blue Peter, and the recreated A1 Tornado. Originally Kylchap exhausts were expensive and rarely used because the design was patented and subject to a licence fee but, after the patent expired, many more locomotives were retrofitted, including all the remaining A3 and A4 class, as the pure manufacturing cost was relatively low. The last steam express passenger locomotive built in Britain, Duke of Gloucester, was not fitted with a Kylchap exhaust in service, despite plans to fit one, but one was fitted in preservation when it was realised that poor draughting had been one of the biggest reasons behind its poor performance in its service days. A Kylchap exhaust is fitted to the Stainmore Railway company industrial 0-4-0st locomotive 'F C Tingey', found at Kirkby Stephen East station. These exhausts were also fitted to some British-built export locomotives, primarily Garratt locomotives for Africa.

Czechoslovakia

The only other nation to take them up in quantity was Czechoslovakia, where all late normal gauge steam locomotives used this exhaust design.

Other exhaust systems

The Kylchap was not the only advanced steam locomotive exhaust. Another design, the Lemaître, had some success in France and England. The noted Argentinian engineer, Livio Dante Porta, designed several: the Kylpor, Lempor and Lemprex systems. Several U.S. railroads, including the Norfolk & Western, used a concentric nozzle known as the "waffle iron exhaust".