Leavitt Hunt | |

|---|---|

| Born | February 22, 1830 Brattleboro, Vermont |

| Died | February 16, 1907 (aged 75–76) Weathersfield, Vermont |

| Place of burial | Weathersfield Bow Cemetery, Weathersfield, Vermont |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service/ | Union Army |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | 38th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, Army of the Potomac; Adjutant General's Corps; War Department |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Other work | Photographer, attorney, farmer, inventor, art collector |

Col. Leavitt Hunt [1](1831–February 16, 1907) was a Harvard-educated attorney and photography pioneer who was one of the first people to photograph the Middle East. He and a companion, Nathan Flint Baker, traveled to Egypt, the Holy Land, Lebanon, Turkey and Greece on a Grand Tour in 1851–52, making one of the earliest photographic records of the Arab and ancient worlds, including the Great Sphinx and the Great Pyramid of Giza, views along the Nile River, the ruins at Petra and the Parthenon in Greece.

Biography

The youngest son of General Jonathan Hunt of Vermont and the former Jane Maria Leavitt, and brother to architect Richard Morris Hunt and painter William Morris Hunt,[n 1] Leavitt Hunt was born in Brattleboro, Vermont, but grew up in Paris following the early death of his father Jonathan Hunt, a Vermont Congressman whose father had been the state's Lieutenant Governor.[2]

Leavitt Hunt attended the Boston Latin School,[3] and subsequently enrolled in a Swiss boarding school, finally taking a law degree from the University of Heidelberg. He then enrolled at the Swiss Military Academy in Thun. Hunt was a scholar: he was fluent in French, German, Italian, Latin, Greek and Hebrew, and could write in both Persian and Sanskrit.[n 2]

Hunt's companion on his Middle Eastern journey was a wealthy sculptor from Ohio and friend of the Hunt family. Nathan Flint Baker had been travelling in Europe for a decade, and announced his intention to travel through the Middle East. Hunt decided to join him, meeting him in Florence, Italy, in late September 1851.

Hunt and Baker spent several weeks in Rome practicing photography, and then sailed from Naples to Malta and eventually up the Nile River into the Sinai Peninsula, to Petra (where they were among the first to photograph the ruins), then on to Jerusalem, to what is today Lebanon, then on to Constantinople and Athens, before returning to Paris in May 1852.

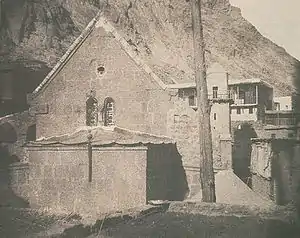

Hunt's and Baker's photographs were dazzling, especially for a brand-new medium many had never seen before. They photographed the Great Sphinx and the Pyramids at Giza, the templex complex at Karnak, the Ramesseum at Thebes, and the ruins on the Island of Philae. They travelled farther to photograph the Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai, the tombs and temples of Petra, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the ruins at Baalbek, and finally the buildings of the Acropolis in Athens.

The 60 extant photographs from their journey show that Hunt and Baker were keen on the new medium and familiar with its techniques. It was a real partnership: both men brought their own strengths to the process, and images that survive demonstrate their aesthetic acumen as well as their journalistic desire to show the settings in which they worked. One image of an unveiled Ghawazee female dancer, signed on the negative by Hunt himself, is likely the earliest photographic portrait of a Middle Eastern woman. Another image of the less photogenic view from the rear of the Parthenon demonstrates two men unafraid to indulge their take on a revered landmark.

The trip was a logistical challenge. Accompanying the two travelers for part of the journey were Leavitt Hunt's older brother, the architect Richard Morris Hunt, and two other friends. The group hired a dahaheah[n 3] and a crew of 13 Egyptians to take them down the Nile River. Architect Hunt, later famous for his Gilded Age Newport palazzos, painted and made sketches along the Nile while his younger brother and Baker took photographs. (The results were later shown at a 1999 exhibition in Washington, D.C.)

Following their arduous journey, the pair of no-longer-neophyte photographers returned to Paris and made prints from their 18x24 cm negatives which were made using a waxed-paper process.[4] Having developed the negatives, each man kept a personal album of the prints. The young Hunt showed his to the German naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, who brought them to the attention of the King of Prussia, and Hunt made a formal gift of 11 prints to Karl Richard Lepsius, the German founder of the study of ancient Egyptology.[5] Baker left his album with a New York dealer to discern commercial interest in the prints.

Following their extraordinary journey, the two men took divergent paths. Baker returned to Cincinnati, Ohio, to enjoy the life of a wealthy aesthete, while Hunt completed his studies at the Swiss Military Institute, then returned to America, where he took a second law degree, this one from Harvard.[6] He began practicing law in New York City, the home of his brother Richard Morris Hunt, until the outbreak of the American Civil War, when he enlisted as lieutenant on the staff of General Heintzelman. Eventually he was promoted to lieutenant colonel for bravery at the Battle of Malvern Hill.[7] Hunt subsequently attained the rank of full colonel and assistant adjutant general in the Union Army.[8]

Following the Civil War, Leavitt Hunt returned to New York City and his law practice for several years, until he retired in 1867 to Weathersfield, Vermont, where his wife Katherine Jarvis [9] had inherited the estate belonging to her father William Jarvis, a prominent Vermont businessman and diplomat best known as the first importer of Merino sheep into America.

Leavitt Hunt purchased his own estate at nearby Weathersfield Bow and became a gentleman farmer.[5] Hunt was particularly interested in the rare breeds of Dutch cattle that he raised,[10] as well as the white pine forests he propagated on his estate, which he dubbed Elmsholme.[11] During his retirement as a farmer, Hunt also became an inventor,[12] with several patents for new plows.[13][14]

As far as is known, neither Hunt nor his companion Baker ever showed much interest in the photographic medium after their journey. Their prints are rarely seen, very scarce, and are among the most valuable early photographic images. Hunt's personal album is now in the collection of the Bennington Art Museum, Bennington, Vermont. Baker's album evidently disappeared. The collection of photos presented to Egyptologist Richard Lepsius is housed at the Museum Ludwig's AgfaPhoto-Historama in Cologne, Germany.

Hunt's personal negatives are believed lost, but the prints he made became the property of his brother Richard Morris Hunt. They are now preserved in the Richard Morris Hunt Papers at the American Architectural Foundation in Washington, D.C. A 1999 show at the American Architectural Foundation's Octagon Museum showcased Leavitt Hunt's 1853 journey. Entitled "A Voyage of Discovery: The Nile Journal of Richard Morris Hunt", the exhibition consisted of seventy of Leavitt Hunt's original photographic prints, as well as drawings and watercolors by Richard Morris Hunt from the museum's Prints and Drawings Collection.[15]

Some of Leavitt Hunt's personal prints were donated by his family after his death to the Library of Congress, where they are part of the permanent photographic collection.[16] There are also a few original prints from this early Middle East trip in the Hallmark Photographic Collection and at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York. Harvard University's Harrison D. Horblit Collection of Early Photography also owns several of the works by Hunt and Baker.

Although Leavitt Hunt never returned to photography, he remained vitally interested in the arts until the end of his life, corresponding with fellow Harvard-educated lawyer and author Henry Dwight Sedgwick, as well as other intellectuals of the era.[17] He and his wife travelled frequently, often crossing paths with family friends like Joseph Hodges Choate and Thomas Jefferson Coolidge.[18] He also wrote poetry on the side.[19]

Perhaps the highest tribute paid Leavitt Hunt and his brothers was that of Ralph Waldo Emerson. "The remarkable families", Emerson wrote, were "the three Jackson brothers....the three Lowell brothers....the four Lawrences....the Cabots....the three Hunts, William, Richard and Leavitt (William Hunt tells also of his brother John, in Paris); the Washburns, three governors, I believe."[20]

Clyde du Vernet Hunt, who graduated from Andover and Harvard Law School, and subsequently became a painter and sculptor accepted by the Paris Salon,[21] was the son of Leavitt Hunt and his wife, the former Katherine Jarvis.[22][23] A portrait of Leavitt Hunt painted by his brother William Morris Hunt in 1874 is in the permanent collection of the Brooks Memorial Library, Brattleboro's main library.[24] Artist William Morris Hunt sketched other members of his brother Leavitt's family as well.[25] Jarvis Hunt, another son of Col. Hunt and his wife, became a noted Chicago architect.[26]

Leavitt Hunt's wife Katherine, daughter of businessman William Jarvis, died June 6, 1916, at Lakewood, New Jersey, and was interred with her husband at Weathersfield.[27] Leavitt Hunt predeceased his wife, dying at Weathersfield on February 16, 1907. The couple's infant son Morris Hunt, who died in 1871, is interred with his parents.[28]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "JONATHAN HUNT" (txt). Part 5 Early Hunts by Mitchell J. Hunt. ancestry.com. October 22, 1999. Retrieved January 5, 2010.The fourth brother was Jonathan Leavitt, a graduate of the University of Paris who became a medical doctor in Paris. Like his brother, painter William Morris Hunt, Jonathan Hunt was an apparent suicide, at age forty-nine in Paris

- ↑ Known as the scholar in the family, Hunt was offered a professorship at Princeton, then known as the College of New Jersey, but turned it down in favor of his interests in the law, travel and the arts.

- ↑ Nezar AlSayyad (January 25, 2001). Consuming tradition, manufacturing heritage: global norms and urban forms in the Age of Tourism (txt). Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 9780415239417. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)A dahaheah was a large houseboat with triangular cross-sails. The rear of the boat sported a cabin, where the chartering party could sleep. Typically, they took their meals on the roof of the cabin under a large awning. This means of conveyance was typically used by English and other foreign tourists on the Nile in the nineteenth century. The crew consisted of a dozen or more men, who cooked, captained the vessel and shopped in the bazaars for supplies.

References

- Inline

- ↑ Leavitt Hunt's birth name was Henry Leavitt Hunt, but he subsequently dropped the Henry.

- ↑ McCullough, David (2011). The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781416576891.

- ↑ (Mass.), Boston Latin School; Jenks, Henry Fitch (28 March 1886). Catalogue of the Boston Public Latin School, Established in 1635: With an Historical Sketch. Boston Latin School Association. p. 186 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ As pioneers of photography, it is unclear how Hunt and Baker learned so much so early. The Englishman William Fox Talbot was still perfecting his Calotype (sometimes called Talbotype) process at the time of the duo's journey. Indeed, it was the year 1852, while Hunt and Baker were embarked on their trip, that one of the early pioneers of Talbot's work, the English inventor, geologist and Royal Society member Levett Landon Boscawen Ibbetson showed his new book using the Talbot process at a London Society of Arts exhibition.

- 1 2 Cabot, Mary Rogers (1922). Annals of Brattleboro, 1681-1895. Press of E. L. Hildreth & Company. p. 724 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ School, Harvard Law (28 March 2018). "Quinquennial Catalogue of the Law School of Harvard University". The School – via Google Books.

- ↑ Thompson, Jerry D. (28 March 2018). Civil War to the Bloody End: The Life and Times of Major General Samuel P. Heintzelman. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9781585445356 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "The Civil War Defenses of Washington: Historic Resource Study, National Park Service". nps.gov.

- ↑ The Life and Times of Hon. William Jarvis: Of Weathersfield, Vermont. Hurd and Houghton. 28 March 1869. p. 389 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Mining, Vermont State Board of Agriculture, Manufacturers and (28 March 1872). "Annual Report of the Vermont State Board of Agriculture, Manufactures and Mining ..." The Board – via Google Books.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Social Register, New York. Social Register Association. 28 March 1896. p. 181 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ "Improvement in plow". google.com.

- ↑ "Annual Report of the Commissioner of Patents". U.S. Government Printing Office. 28 March 1871 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Improvement in sulky-ploughs". google.com.

- ↑ A Voyage of Discovery: The Nile Journal of Richard Morris Hunt, 1999, The Octagon Museum, The Museum of the American Architectural Foundation, archfoundation.org Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hunt's daughter Maud Hunt (Mrs. William E. Patterson) donated 26 Hunt prints to the Library of Congress in 1947, including views in Egypt, Greece, Jerusalem, and along the Nile River, including views of temples, tombs and ruins.

- ↑ "Sedgwick Family Papers, 1717-1946". www.masshist.org.

- ↑ Autograph File, Houghton Library, Harvard College Library, Harvard University, lib.harvard.edu

- ↑ Nature and Art: Poems and Pictures from the Best Authors and Artists. Estes and Lauriat. 28 March 1881. p. 12 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Ralph Waldo Emerson (1914). Edward Waldo Emerson and Waldo Emerson Forbes (ed.). Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1864–1876. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 269.

- ↑ "The Phillipian, Phillips Andover Academy, Andover, Mass., April 24, 1897" (PDF). phillipian.net.

- ↑ "Workshops & Classes - Bennington Museum - Grandma Moses - Vermont History and Art". www.benningtonmuseum.org.

- ↑ Rarely Viewed Hunt Family Work on View at the Bennington Museum, benningtonmuseum.org

- ↑ Newspapers and magazines of the day carried news that Leavitt Hunt was writing a biography of his brother the painter, but this work never appeared. Apparently Leavitt Hunt's intentions were supplanted by the 1899 volume Life of William Morris Hunt, written by William Morris Hunt's longtime student Helen Mary Knowlton.

- ↑ Boston, Museum of Fine Arts (28 March 1880). Exhibition of the Works of William Morris Hunt. A. Mudge & son, printers. p. 49 – via Internet Archive.

leavitt hunt.

- ↑ "Annals of Brattleboro, Volume II, Chapter LXIX". ibrattleboro.com. Archived from the original on 2011-01-29. Retrieved 2010-01-07.

- ↑ "Obituary, Katherine Jarvis Hunt, The New York Times, June 6, 1916, nytimes.com" (PDF). The New York Times.

- ↑ "~ ~ WEATHERSFIELD BOW CEMETERY ~ ~". robinlull.com.

- General

Further reading

- A Voyage of Discovery: The Nile Journal of Richard Morris Hunt, 1999, The Octagon Museum, The Museum of the American Architectural Foundation, Washington, D.C.

- Exploration, Vision & Influence: The Art World of Brattleboro's Hunt Family, Catalogue, Museum Exhibition, The Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont, June 23–December 31, 2005, Paul R. Baker, Sally Webster, David Hanlon, and Stephen Perkins

- See also William Fox Talbot, inventor of the Calotype, sometimes called the Talbotype, the medium used by Hunt and Baker

- Pilgrims on Paper: The Calotype Journey of Leavitt Hunt and Nathan Flint Baker, David R. Hanlon, History of Photography, December 2007

External links

- Great Pyramid and Sphinx, Gizeh, Egypt, Calotpye print, ca. 1852, Leavitt Hunt, Prints & Photographs Reading Room, The Library of Congress, www.loc.gov.rr

- Agrippa; or, The Evangelists: Historical Point of View, Leavitt Hunt, Miller & Curtis, New York, 1857