| Leucostoma canker | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. persoonii |

| Binomial name | |

| Leucostoma persoonii | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Valsa persoonii Nitschke (1870) | |

Leucostoma canker is a fungal disease that can kill stone fruit (Prunus spp.).[1] The disease is caused by the plant pathogens Leucostoma persoonii[2] and Leucostoma cinctum[3] (teleomorph) and Cytospora leucostoma and Cytospora cincta[4] (anamorphs). The disease can have a variety of signs and symptoms depending on the part of the tree infected. One of the most lethal symptoms of the disease are the Leucostoma cankers. The severity of the Leucostoma cankers is dependent on the part of the plant infected. The fungus infects through injured, dying or dead tissues of the trees. Disease management can consist of cultural management practices such as pruning, late season fertilizers or chemical management through measures such as insect control. Leucostoma canker of stone fruit can cause significant economic losses due to reduced fruit production or disease management practices. It is one of the most important diseases of stone fruit tree all over the world.

Hosts and symptoms

The hosts for Leucostoma canker include stone fruits such as cultivated peach, plum, prune, cherry (Prunus spp.), or other wild Prunus spp. It can also be found on apple (Malus domestica). Stone fruits are referred to as drupe, which are fruits containing a seed encased by a hard endocarp, surrounded by a fleshy outer portion.

Leucostoma canker symptoms differ depending on where on the tree infection takes place.[5] Discoloration occurs in sunken patches on infected twigs. Light and dark concentric circles of narcotic tissue characterize this symptom, occurring near buds killed by cold or on leaf scars. Infections on the nodes are seen 2–4 weeks after bud break.[6] As time passes, darkening occurs within diseased tissues, and eventually, amber gum ooze may seep from infected tissue.[7] Nodal infections are particularly vulnerable in one-year-old shoots that develop within the center of the tree. If fungal growth persists without treatment, scaffold limbs and large branches will likely become invaded within a short time frame. Cankers occurring on branches that are the product of such infections will contain dead twigs or twig stubs at the canker's center.

The most striking symptom of infection includes cankers located on the main trunk, branch crotches, scaffold limbs, and older branches.[3] A symptom called “flagging” can be found on necrotic scaffold limbs. The cankers are parallel to the long axis of the stem and take on an oval shape. Normally, large-scale production of amber colored gum marks the first external symptom of such cankers. While gum production is the typical plant response to irritation, the gum secretion of Leucostoma occurs in bulk amounts. This gum darkens as time passes, gradually leading to the drying and cracking of bark; thus exposing the blackened tissue below.

As the tree continues to mature in the early growing season, the tree resists additional fungal penetration through the formation of callus rings surrounding the canker. However, the Leucostoma generally reinvades the tissue late in the growing season while the tree switches into dormancy. Due to the alteration of callus production and canker formation, cankers with circular callus rings are usually observed.

Foliar symptoms might develop from branch or twig infections. Symptoms include chlorosis, wilting, and necrosis. Signs include small black structures on dead bark which contain pycnidia.[7]

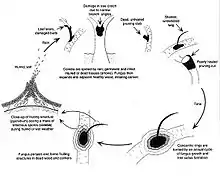

Disease cycle

Although the Leucostoma pathogen can undergo sexual stages, the asexual cycle is far more important for disease development.

The fungus that causes disease overwinters in cankers or previously invaded dead wood. Environmental cues, such as cool, moist weather in the early spring, cause conidia to be released from pycnidia in sticky masses. The conidia are then spread via wind or water splashes. Conidia then germinate and the fungi begins to colonize provided that the environment is wet. The fungus is incapable of invading healthy bark and must enter the tree through injured, dying, or dead tissues.[3] Leucostoma commonly enters through weak, winter-killed twigs in the center of the tree. Moreover, it gains entry through winter-injured wood on limbs and trunks. It also can enter through short, dead pruning stubs, leaf scars, winter-killed buds on small twigs, and on poorly healed pruning cuts.

Upon invasion, fungal growth moves into healthy adjacent tissue. This fungal growth is slow, but the expansion continues even at temperatures just above freezing. As the temperature rises above 50 degrees Fahrenheit, the tree actively starts to grow and a callus is usually formed around the canker. The defense mechanism, however, is outmatched in the fall and following spring when the dormant tree is unable to defend itself. The repeated tree growth eventually forms a new callus, and an annual pattern of callus formation and canker expansion leads to the development of concentric callus rings around the first infection site.

Pycnidia develop throughout the growing season within the colonized tissues. Conidia are then produced inside the pycnidia and can be released when conditions are favorable: i.e. humid weather. As a result, vulnerable tissues are at risk of initial invasion throughout most parts of the year, although it most commonly occurs in autumn and spring following winter injury and leaf scars.

Environment

Leucostoma canker can be found in the Northeastern United States, from the cooler regions surrounding Lake Ontario to the warmer areas in the lower Hudson Valley. It can also be found the Southeastern United States on peaches. In California and Idaho, it has been found on plum and prune trees. In Europe, the disease can be found on apricot, peach, and cherry. Leucostoma canker has also been witnessed in South America and Japan.[1]

The spread of disease is favored in cool, wet, and humid conditions in late fall or early spring when conidia are most abundant. Regions with irrigation are particularly vulnerable to disease, for conidia thrive whenever water is available. Studies have shown that there are positive correlations between the number of disease causing agents (conidia), and the number of hours that temperatures are between 10 and 15 degrees Celsius. These data also correlate to the duration of moisture and amount of time humidity conditions are above 90 percent. These conditions are all optimal for disease. Without humidity and wet conditions, disease does not occur.

Management

Control of Leucostoma Canker is possible through a combination of pest and crop management techniques following life cycles of the trees. The strategy is implemented following techniques aimed at reducing number of pathogenic inoculum, minimizing dead or injured tissues to prevent infection, and improving tree health to improve rapid wound healing. Chemical controls have not been very effective at controlling this disease with no fungicides registered specifically for control of Leucostoma spp., and demethylation-inhibiting (DMI) fungicides having almost no effect on L. persoonii.[1]

Cultural management

There are many strategies to cultural management. Establishment of new trees that are disease free by trying to plant trees as soon as they are received from the nursery to reduce the amount of stress the tree undergoes to reduce the amount of dead tissue. Apply insecticides to prevent insects such as, peach tree borer to prevent disease causing conidia from entering wounded parts of the tree that the insects create. Prune trees appropriately and at the correct time when buds start to break to promote wide angled branching. Infection at pruning sites is less common when done during late spring because of the smaller amount of inoculum present at this time. Inspect trees occasionally and removed any dead branches to prevent infection at these sites. Training trees properly also helps foster decreased amount of disease. Training trees during the first season to have branches develop wide crotch angles to sustain long orchard life. Avoid excessive and late fertilization during cold season to avoid low temperature injury. Fertilize trees during the early spring to prevent cold-susceptible growth.[1]

Genetic resistance

Selecting cultivars is important and the best ones are the cultivars resistant to cold temperatures. As plant pathologists have learned better ways to develop more efficient resistance to the Leucostoma canker pathogens, there have been many really effective cultivars developed that can be used. However, the cultivars that offer the best resistance to cold temperatures have a higher ability to resist infection due to injury or wounding. A peach cultivar resistant to cold temperatures would be Redhaven one that is especially, recommended for Missouri and some nectarine cultivars include RedGold, Crimson Snow, Crimson Gold, Sunglo and many more.[8]

Importance

Leucostoma canker[9] is one of the most important diseases on stone fruit. Leucostoma persoonii[10] is most significant on peaches, nectarines, and cherries in regions with cold winters. The first records of peach tree cankers caused by this pathogen were documented in western New York in 1900. The disease was then sighted in southern Ontario twelve years later.[1] Leucostoma canker decreases the bearing surface of fruiting trees and shortens the tree’s lifespan. Additionally, it considerably raises the costs of disease management.

As limbs with cankers die or break off due to the stress of holding fruit, economic losses add. Parts of the branch distal to the canker often become less fruitful, and eventually the canker will enlarge to reach the branch, effectively killing it. Trees with numerous cankers show strikingly reduced yield. Since peach trees are trimmed to hold 3 to 4 main scaffold limbs, the death of even one of the main limbs causes a 25 to 50% loss of fruit production.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Leucostoma canker of stone fruits". Apsnet.org.

- ↑ Jensen, Carolyn J. P.; Adams, Gerard C. (1 January 1995). "Nitrogen Metabolism of Leucostoma persoonii and L. cincta in Virulent and Hypovirulent Isolates". Mycologia. 87 (6): 864–875. doi:10.2307/3760862. JSTOR 3760862.

- 1 2 3 Biggs, Alan R. "Leucostoma Canker of Stone Fruits". Caf.wvu.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ↑ Wensley, R. N. (1 March 1971). "The microflora of peach bark and its possible relation to perennial canker (Leucostoma cincta (Fr.) v. Hohnel (Valsa cincta))". Can. J. Microbiol. 17 (3): 333–337. doi:10.1139/m71-056. PMID 5551316.

- ↑ "Leucostoma facts" (PDF). Fruit.cornell.edu. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ↑ "Search". Nysipm.cornell.edu.

- 1 2 "Fungal Cankers of Trees -- Sustainable Urban Landscapes". Store.extension.iastate.edu. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ↑ "MG6 Fruit Production - University of Missouri Extension". Extension.missouri.edu.

- ↑ Puterka, G. J.; Scorza, R.; Brown, M. W. (1 November 1993). "Reduced Incidence of Lesser Peachtree Borer and Leucostoma Canker in Peach-Almond Hybrids". J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 118 (6): 864–867. doi:10.21273/JASHS.118.6.864.

- ↑ Adams, Gerard C.; Surve-Iyer, Rupa S.; Iezzoni, Amy F. (1 January 2002). "Ribosomal DNA Sequence Divergence and Group I Introns within the Leucostoma Species L. cinctum, L. persoonii, and L. parapersoonii sp. nov., Ascomycetes That Cause Cytospora Canker of Fruit Trees". Mycologia. 94 (6): 947–967. doi:10.2307/3761863. JSTOR 3761863. PMID 21156569.