| Sarcosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

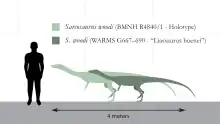

| Skeletons of the known specimens of Sarcosaurus woodi (restored as a ceratosaur) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Neotheropoda |

| Genus: | †Sarcosaurus Andrews, 1921 |

| Type species | |

| †Sarcosaurus woodi Andrews, 1921 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Sarcosaurus (Latin: "flesh lizard") is a genus of basal neotheropod dinosaur, roughly 3.5 metres (11 ft) long. It lived in what is now England and maybe Ireland and Scotland during the Hettangian-Sinemurian stages of the Early Jurassic, about 199-196 million years ago. Sarcosaurus is one of the earliest known Jurassic theropods, and one of only a handful of theropod genera from this time period. Along with Dracoraptor hanigani it is one of the two described neotheropods from the lowermost Jurassic of the United Kingdom.[1]

Description

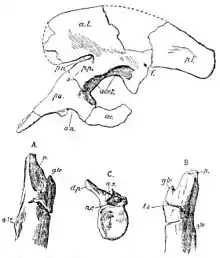

The holotype is NHMUK PV R4840 a partial skeleton that includes a posterior dorsal vertebra, partial left and right ilia, that are fused to the proximal portion of the pubis, lacking the femoral head. The specimen shows some evidence of skeletal maturity, meaning it is not an early juvenile, but its exact ontogenetic stage cannot be ascertained.[1] Referred specimens include the non mature NHMUK PV R3542 (holotype of Sarcosaurus andrewsi) that includes a complete right tibia; WARMS G667–690, a partial skeleton of a single individual that includes posterior dorsal vertebra, middle caudal vertebra, dorsal rib fragments, left ilium, right and left pubes, femora and tibiae, proximal end of left fibula, probable distal half of fibula, distal portions of metatarsals IV, II or III proximal half of left pedal phalanx II-1, and three indeterminate bone fragments.[1][2] Sarcosaurus shares certain morphological conditions with other neotheropods, including Liliensternus liliensterni (collateral fossae of the metatarsal II with similar development and shape on both sides, larger ratio on the centrum) and Dilophosaurus wetherilli (lateral collateral fossa is bigger than the medial one in the metatarsal, middle caudal series proportionately lower and narrower than the middle−posterior dorsal vertebra). Sarcosaurus was a bipedal predator, probably able to run fast and catch small prey. The holotype belonged to a 3.5-metre-long animal whose weight was no greater than 50–60 kg. NHMUK PV R3542 belonged to a larger animal, estimated to have had a maximum length of 5 m and a weight of 140 kg.[3]

History of discovery

The fossils of Sarcosaurus were found in the Lower Lias of England. The type species, Sarcosaurus woodi, was first described by Charles William Andrews in 1921 shortly after a partial skeleton had been found by S.L. Wood near Barrow-on-Soar, in the Scunthorpe Mudstone. The generic name is derived from Greek sarx, "flesh". The specific name honours Wood. The holotype, BMNH 4840/1, consists of a pelvis, a vertebra and the upper part of a femur. The preserved length of the femur is 31.5 centimetres (12.4 in).[4] A second species, Sarcosaurus andrewsi, was named by Friedrich von Huene in 1932,[5] based on a 445-millimetre (17.5 in) tibia, BMNH R3542, described by Arthur Smith Woodward in 1908 and found near Wilmcote.[6] Confusingly von Huene in the same publication named the very same fossil Magnosaurus woodwardi. Later he made a choice for S. andrewsi to be the valid name.[7] Huene also discussed WARMS G667–690, a partial skeleton also from Wilmcote, both specimens are from the Blue Lias. In 1974 S. andrewsi was reclassified as Megalosaurus andrewsi by Michael Waldman, on the probably erroneous assumption it was a megalosaurid.[8] A later study concluded the two species to be indistinguishable except for size, but other authors consider any identity to be unprovable as there are no comparable remains and conclude both species to lack autapomorphies and therefore to be nomina dubia.[9] Von Huene in 1932 referred a partial skeleton from the collection of the Warwick Museum to S. woodi but the identity was unproven; in 1995 it was given the informal name "Liassaurus"[10] but this has remained a nomen nudum. The specimen is likely one individual, located in the same stratiagraphic position as the holotypic specimen. Unfortunately, there are few available overlapping elements from the specimen and the holotype. Both specimens preserve a relatively complete femur: however, the features of both (an anteromedially directed head, a relatively long fourth trochanter and a trochanteric shelf) are plesiomorphic and thus do not indicate conspecifity or clade membership. It is noted, however, that there are no features which are present in one specimen but not the other. In 2020 WARMS G667–690 was given a comprehensive redescription, which proposed that all three specimens belonged to the same species, Sarcosaurus woodi.[1]

Between the years 1980 and 2000, three fossils were discovered on a beach near The Gobbins in Northern Ireland by palaeontologist Roger Byrne. Exact geologic provenance is not reported for any of the specimens, but the very dark colouration of the specimens indicate (through means of comparison to marine fossils in other Northern Irish localities) they hail from Lias Group rocks, likely from either the Planorbis Zone or the Pre-planorbis Zone of the Waterloo Mudstone Formation. Along specimens referred to Scelidosaurus a tibia was recovered, BELUM K12493, referred to an indeterminate neotheropod, probably related to Sarcosaurus or from an indeterminate megalosauroid. The scelidosaur femur and theropod tibia are the only known remains of dinosaurs from Ireland, which has a poor Mesozoic fossil record entirely consisting of marine localities, and the scelidosaur specimen was the first ever reported from the island.[11]

In 2023, a partial Theropod Specimen recovered from the lower Sinemurian Broadford Beds Formation of the Isle of Skye, previously referred to a Coelophysoid-grade theropod, was reclassified as Cf.Sarcosaurus, clading with Tachiraptor as a branch leading to Averostra. This specimen, NMS G.1994.10.1, consists on an isolated left tibia lacking its proximal region.[12]

Phylogeny

Andrews originally assigned Sarcosaurus to the Megalosauridae. The first to suggest a more basal position was Samuel Paul Welles who placed it in the Coelophysidae.[13] Later analyses resulted in either a position in the Ceratosauria,[14] or in the Coelophysoidea.[15] Ezcurra (2012) found Sarcosaurus to be the most basal ceratosaur in a large unpublished analysis.[16] In 2018, Andrea Cau in the large analysis of Saltriovenator found Sarcosaurus to be a dilophosaurid with good amount of support in the data.[17] In 2020, Ezcurra et al. recovered Sarcosaurus as a close relative of Averostra due to the presence of shared characters including an anteroventrally oriented ventral margin of the preacetabular process in lateral view on the ilium and a femur with a poorly posteriorly developed fourth trochanter. Their cladogram is shown below:[1] A latter work reinforced that clade made of Sarcosaurus woodi + (Tachiraptor admirabilis + Averostra).[12]

| Theropoda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palaeoenvironment

Holotype specimen was collected from strata (bucklandi zone, Sinemurian) that were deposited in epicontinental, shallow, marine settings affected by sea-level fluctuations and a warm, predominantly humid climate.[18] In south-western Warwickshire, is represented by the upper part of the Rugby Limestone Member (Hettangian-Sinemurian) of the Blue Lias Formation. with typical lithofacies of alternating mudrocks and generally fine-grained and frequently highly fossiliferous limestones.[19] the Rugby Limestone Member was deposited at a palaeolatitude of approximately 35° N in a storm-influenced offshore setting.[20] Wilmcote was related to the eastern margin of the Worcester Graben during the Early Jurassic and adjacent to the East Midlands Shelf.[21] The western margin of the emergent London Platform at 60–80 km to the south-east was probably the principal source of terrestrial biodebris.[22]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ezcurra, M. D.; Butler, R. J.; Maidment, S. C. R.; Sansom, I. J.; Meade, L. E.; Radley, J. D. (2020). "A revision of the early neotheropod genus Sarcosaurus from the Early Jurassic (Hettangian–Sinemurian) of central England". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 191: 113–149. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa054. hdl:11336/160038.

- ↑ Carrano, Matthew T.; Sampson, Scott D. (2004-09-27). "A review of coelophysoids (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Jurassic of Europe, with comments on the late history of the Coelophysoidea". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie – Monatshefte. 2004 (9): 537–558. doi:10.1127/njgpm/2004/2004/537. ISSN 0028-3630.

- ↑ "List of Theropods", Dinosaur Facts and Figures, Princeton University Press, pp. 248–285, 2019-06-25, doi:10.2307/j.cdb2hnszb.15, S2CID 243596687, retrieved 2023-10-19

- ↑ Andrews, Charles W. (1921). "LVI.—On some ramins of a Theropodous dinosaur from the Lower Lias of Barrow-on-Soa". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 8 (47): 570–576. doi:10.1080/00222932108632620. ISSN 0374-5481.

- ↑ Von Huene, F. (1932). "Die fossile Reptil-Ordnung Saurischia, ihre Entwicklung und Geschichte". Monographien zur Geologie und Palaeontologie. 1 (4): 361. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ↑ Woodward, A. Smith (1908). "Note on a Megalosaurian tibia from the lower Lias of Wilmcote, Warwickshire". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 1 (3): 257–259. doi:10.1080/00222930808692397. ISSN 0374-5481.

- ↑ Savage, Jay M.; von Huene, Friedrich R. Freiherr (1957-04-05). "Palaontologie und Phylogenie der Niederen Tetrapoden". Copeia. 1957 (1): 68. doi:10.2307/1440541. ISSN 0045-8511. JSTOR 1440541.

- ↑ Waldman, M. (1974). "Megalosaurids from the Bajocian (Middle Jurassic) of Dorset". Paleontology. 17 (2): 325–339. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ↑ Naish, Darren; Martill, David M. (2008-04-09). "Dinosaurs of Great Britain and the role of the Geological Society of London in their discovery: basal Dinosauria and Saurischia". Journal of the Geological Society. 165 (3): 613–623. doi:10.1144/0016-76492007-154. ISSN 0016-7649. S2CID 129624992.

- ↑ Pickering, S. (1995). Jurassic Park: Unauthorized Jewish Fractals in Philopatry. A Fractal Scaling in Dinosaurology Project (2 ed.). Capitola. p. 478.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Simms, Michael J.; Smyth, Robert S.H.; Martill, David M.; Collins, Patrick C.; Byrne, Roger (2021). "First dinosaur remains from Ireland". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 132 (6): 771–779. Bibcode:2021PrGA..132..771S. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2020.06.005. S2CID 228811170.

- 1 2 Ezcurra, Martín D.; Marke, Daniel; Walsh, Stig A.; Brusatte, Stephen L. (2023). "A revision of the 'coelophysoid-grade' theropod specimen from the Lower Jurassic of the Isle of Skye (Scotland)". Scottish Journal of Geology. 59 (1): 012. Bibcode:2023ScJG...59...12E. doi:10.1144/sjg2023-012. S2CID 264343748.

- ↑ Welles, S.P. (1984). "Dilophosaurus wetherilli (Dinosauria, Theropoda): osteology and comparisons". Palaeontographica Abteilung A. 185: 85–180. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ↑ Gauthier, J. A. (1986). "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds". Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. 8 (1): 1–55. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ↑ Carrano, Matthew T.; Hutchinson, John R.; Sampson, Scott D. (2005-12-30). "New information onSegisaurus halli, a small theropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Arizona". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 835–849. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0835:niosha]2.0.co;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 30039789.

- ↑ Ezcurra, M. (2012). "Phylogenetic analysis of Late Triassic – Early Jurassic neotheropod dinosaurs: Implications for the early theropod radiation". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Program and Abstracts. 32: 1–91.

- ↑ Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Maganuco, Simone; Cau, Andrea (2018). "The oldest ceratosaurian (Dinosauria: Theropoda), from the Lower Jurassic of Italy, sheds light on the evolution of the three-fingered hand of birds". PeerJ. 6: e5976. doi:10.7717/peerj.5976. PMC 6304160. PMID 30588396.

- ↑ Hesselbo, Stephen P. (2008). "Sequence stratigraphy and inferred relative sea-level change from the onshore British Jurassic". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 119 (1): 19–34. Bibcode:2008PrGA..119...19H. doi:10.1016/s0016-7878(59)80069-9. ISSN 0016-7878.

- ↑ Ambrose, Keith (2001). "The lithostratigraphy of the Blue Lias Formation (Late Rhaetian—Early Sinemurian) in the southern part of the English Midlands". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 112 (2): 97–110. Bibcode:2001PrGA..112...97A. doi:10.1016/s0016-7878(01)80020-1. ISSN 0016-7878.

- ↑ Weedon, Graham P.; Jenkyns, Hugh C.; Page, Kevin N. (2017-01-30). "Combined sea-level and climate controls on limestone formation, hiatuses and ammonite preservation in the Blue Lias Formation, South Britain (uppermost Triassic – Lower Jurassic)". Geological Magazine. 155 (5): 1117–1149. doi:10.1017/s001675681600128x. hdl:10026.1/8505. ISSN 0016-7568. S2CID 133014351.

- ↑ Radley, J.D. (2003). "Warwickshire's Jurassic geology, past,present and future" (PDF). Mercian Geologist. 15 (1): 209–218. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ↑ Cox, BM; Sumbler, MG; Ivimey-Cook, HC (1999). "A formational framework for the Lower Jurassic of England and Wales (onshore area)". British Geological Survey Research Report. 99 (1): 1–28. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

.jpg.webp)