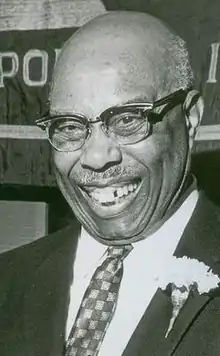

Lionel Artis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 3, 1895 |

| Died | September 1, 1971 (aged 75) Indianapolis, Indiana, Indiana, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Administrator |

Lionel F. Artis (1895 – 1971) was a civil servant and administrator in the United States. Artis became the first Black person to be appointed to a policy-making municipal agency in Indianapolis when he was a named a member of the Indianapolis Board of Health and Hospitals.

Early life

Artis was born in Paris, Illinois. His family moved to Indianapolis when he was a child. He served in the U.S Army during World War I and studied in Beaune, France while in Europe. [1]

He studied at Butler University before transferring to the University of Chicago where he earned his bachelor of arts in 1933. In 1941, he earned his master of arts from Indiana University.[1]

Artis married Sue Chambers and they had four children.[2]

Civil service

Career

Artis was an affordable housing administrator. During the 1920s he opposed segregation including the building of an all-Black high school alongside Robert Brokenburr. Despite organizing efforts, the Indianapolis school board approved the school to be built in 1922. That school would be Crispus Attucks High School.[3] He managed Lockefield Gardens, the first community housing complex in Indianapolis, from 1937 to 1969.[1][4] He also organized the Flanner House Homes, single and duplex family dwellings built in the 1950s for Black families.[1]

Volunteerism

Artis served on the board of 23 organizations in Indianapolis and volunteered for many, including the Community Health Association, Community Service Council of Metropolitan Indianapolis, the Indianapolis Urban League, YMCA, Community Action Against Poverty, Meals on Wheels, Girl Scouts, and more.[1]

As a board member of the historic Senate Avenue YMCA, he introduced the first Boy Scouts troop to the organization.[1] While serving as assistant secretary at YMCA, communicated with James Weldon Johnson about the possibility of King Nana Amoah III, of the Fastis in the Gold Coast of Africa, visiting the city during his visit across country visiting Black communities.[5] An African American art collector, Artis also organized art exhibitions at YMCA.[6]

He became the first Black person to be appointed to a policy-making municipal agency when he was named to the board of the Indianapolis Board of Health and Hospitals.[1]

He was an active member of Kappa Alpha Psi. Artis was the first editor of the fraternity's quarterly publication, The Journal.[7] In the 1920s, Artis corresponded with W.E.B. Du Bois, to whom he submitted pieces about the fraternity for The Crisis. Two of the pieces he submitted were returned by Du Bois.[8][9]

Later life and legacy

In 1967, Artis was named "Man of the Year" by the B'nai B'rith Lodge 58 and "Most Wanted Man" by the Community Service Council. He was also honored by the Indianapolis Urban League, the Jewish Community Relations Council, Family Service Association, and Fall Creek YMCA.[1]

Artis died on September 1, 1971.[1] The service was led by Bishop John Craine at Christ Church Cathedral. Cleo W. Blackburn attended the funeral.[10] Artis is buried at Crown Hill Cemetery.[2]

His papers reside in the collection of the Indiana Historical Society.[1] An apartment complex is named after Artis in Indianapolis.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Zellers, Elizabeth. "Lionel F. Artis Papers, 1933-1967" (PDF). Indiana Historical Society. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- 1 2 "Lionel Franklin Artis". Find A Grave. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ Paul Finkelman (2009). Encyclopedia of African American History: 5-Volume Set. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 500. ISBN 978-0-19-516779-5.

- ↑ "Lionel Artis". The Indianapolis Star. Newspapers.com. 25 April 1938. p. 9. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ Johnson, James Weldon. "Letter from Indianapolis Young Men's Christian Association to James Weldon Johnson, October 2, 1925". Indianapolis Young Men's Christian Association . Colored Men's Branch. University of Massachusetts. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ "African American Fine Art Auction". Tyler Fine Art. Issuu. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ "Chapter History". Indy Kappa. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ Du Bois, W.E.B. "Letter from W. E. B. Du Bois to Kappa Alpha Psi Journal, May 18, 1925". credo.library.umass.edu. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ Du Bois, W.E.B. "Letter from W. E. B. Du Bois to Kappa Alpha Psi Journal, February 13, 1925". W. E. B. Du Bois Papers. University of Massachusetts. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Civil Rights Digital Library". Civil Rights Digital Library. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ Emmis Communications (October 1999). Indianapolis Monthly. Emmis Communications. p. 92.