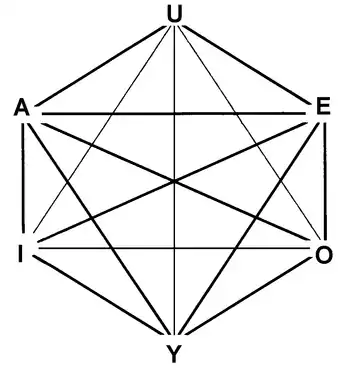

In philosophical logic, the logical hexagon (also called the hexagon of opposition) is a conceptual model of the relationships between the truth values of six statements. It is an extension of Aristotle's square of opposition. It was discovered independently by both Augustin Sesmat and Robert Blanché.[1]

This extension consists in introducing two statements U and Y. Whereas U is the disjunction of A and E, Y is the conjunction of the two traditional particulars I and O.

Summary of relationships

The traditional square of opposition demonstrates two sets of contradictories A and O, and E and I (i.e. they cannot both be true and cannot both be false), two contraries A and E (i.e. they can both be false, but cannot both be true), and two subcontraries I and O (i.e. they can both be true, but cannot both be false) according to Aristotle’s definitions. However, the logical hexagon provides that U and Y are also contradictory.

Interpretations

The logical hexagon may be interpreted in various ways, including as a model of traditional logic, quantifications, modal logic, order theory, or paraconsistent logic.

For instance, the statement A may be interpreted as "Whatever x may be, if x is a man, then x is white."

(x)(M(x) → W(x))

The statement E may be interpreted as "Whatever x may be, if x is a man, then x is non-white."

(x)(M(x) → ~W(x))

The statement I may be interpreted as "There exists at least one x that is both a man and white."

(∃x)(M(x) & W(x))

The statement O may be interpreted as "There exists at least one x that is both a man and non-white."

(∃x)(M(x) & ~W(x))

The statement Y may be interpreted as "There exists at least one x that is both a man and white and there exists at least one x that is both a man and non-white."

(∃x)(M(x) & W(x)) & (∃x)(M(x) & ~W(x))

The statement U may be interpreted as "One of two things, either whatever x may be, if x is a man, then x is white or whatever x may be, if x is a man, then x is non-white."

(x)(M(x) → W(x)) w (x)(M(x) → ~W(x))

Modal logic

The logical hexagon may be interpreted as a model of modal logic such that

- A is interpreted as necessity

- E is interpreted as impossibility

- I is interpreted as possibility

- O is interpreted as non-necessity

- U is interpreted as non-contingency

- Y is interpreted as contingency

Further extension

It has been proven that both the square and the hexagon, followed by a “logical cube”, belong to a regular series of n-dimensional objects called “logical bi-simplexes of dimension n.” The pattern also goes even beyond this.[2]

See also

- Logical cube

- Octagon of Prophecies

- Square of opposition

- Triangle of opposition

References

- ↑ N-opposition theory logical hexagon

- ↑ Moretti, Pellissier

Further reading

- Jean-Yves Beziau (2012), "The power of the hexagon", Logica Universalis 6, 2012, 1-43. doi:10.1007/s11787-012-0046-9

- Blanché (1953)

- Blanché (1957)

- Blanché Structures intellectuelles (1966)

- Gallais, P.: (1982)

- Gottschalk (1953)

- Kalinowski (1972)

- Monteil, J.F.: The logical square of Aristotle or square of Apuleius.The logical hexagon of Robert Blanché in Structures intellectuelles.The triangle of Indian logic mentioned by J.M Bochenski.(2005)

- Moretti (2004)

- Moretti (Melbourne)

- Pellissier, R. "Setting n-opposition" (2008)

- Sesmat (1951)

- Smessaert (2009)